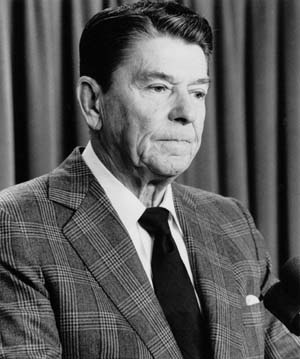

Few American presidents projected the image of Commander-In-Chief more than Ronald Reagan. He snapped salutes at Marine honor guards around the White House with the skill of a Washington, Grant or Eisenhower. While those presidents learned on the battlefield, Reagan was trained by playing all kinds of military men. He battled the Sioux in, “They Died With Their Boots On,” the Nazis in, “Desperate Journey,” and the Nips in, “Flying Leathernecks.”

The movie uniforms were as impeccable as his swagger. Of course, he spent World War II in the safety of Hollywood backlots. “Poor eyesight,” he explained later. But while on center stage at the White House, the Reagan military greeting to the Marine sergeant in dress blues at the steps of Marine One, the president’s helicopter was a fixture in the American mind. The crooked grin with the slightly cupped hand to the right eyebrow marked an aging veteran who doted on the young men and women serving the nation. It was woven into an image that helped Americans feel good about him, themselves and the United States.

For Reagan, the reality of his constitutional command of the armed forces was a rude awakening. He was aroused from sleep at 2:27 AM, on Sunday morning, Oct. 23, 1983. A massive bomb had destroyed the makeshift barracks at Beirut airport for 300 U.S. Marines. Scores were seriously wounded and the final death toll was 241. It was the worst one-day Marine loss since the World War II invasion of the Japanese home island of Okinawa. It was also the worst setback in Reagan’s first term. In only two more months, the 1984 presidential election campaign would begin and an examination of the bloodbath in Beirut – by the media or the Democratic Congress – would be a political disaster.

Even a superficial investigation would show Reagan as a detached chief executive, ignorant of American influence in world affairs and delegating U.S. power to untrained and inept men who knew little more than the aging, absent-minded Commander-In-Chief. A bit of digging would quickly establish:

Repeated warnings of a suicide bomb attack – just like the one that destroyed the American Embassy in Beirut six months earlier – were never relayed by U.S. intelligence to the Marine commander whose troops were already under fire by factions in Lebanon. A pointed alarm about a possible terrorist bomb attack on the Marines by the Central Intelligence Agency on Oct. 20 stopped at the National Security Council in the White House.

Reagan transformed the U.S. Marine role in Lebanon from that of peacekeeping into combat over the bitter objections of his chief military adviser, Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger.

The defense chief requested the withdrawal of the Marines from Beirut during a White House meeting five days before a smiling suicide driver roared past guards with a truck carrying 12,000 pounds of high explosives.

The president had delegated policy decisions to a doubletalking ex-Marine officer who had been passed over for promotion and left the military to enlist in the cause of conservative republicans. Robert MacFarlane, later elevated to the post as Adviser for National Security Affairs, personally ordered the Marines into combat while in Lebanon as Reagan’s personal representative. It was the beginning of MacFarlane’s bumbling in the Mideast that would in three years bring Reagan to the brink of impeachment for exchanging U.S. arms with Iran for American hostages.

MacFarlane, as Reagan’s special representative in the Mideast during his first visit to Damascus, had dismissed Syrian President Hafez al Assad as a kooky mystic who could be pushed around. Yet Assad turned out to be a leading suspect in the Marine bombing as he foiled American support of Israel’s effort to pry Lebanon from historic domination by Syria.

“It was amateur night,” said Robert Dillon, of Reagan’s decisions in the region. Dillon, a career foreign service officer, was U.S. Ambassador in Beirut and dealt with MacFarlane’s visits that led to the Marine tragedy.

For Reagan and his political advisers, eyewitness news reports and grisly television footage of Marine bodies being pulled from the concrete rubble at Beirut airport were damaging beyond their worst nightmares. Orchestrating picture opportunities and images had been at the heart of his presidential popularity.

Yet, not a single critical report by Congress, newspapers or television networks appeared to detail Reagan’s mishandling of events in the Mideast that culminated with the Marine massacre. Media watchdogs as well as Democratically-controlled committees with oversight on military affairs and foreign policy accepted the White House explanation that faulty security by Marine guards was the cause of the tragedy.

There were some exceptions but these vital democratic institutions mainly succumbed to Reagan’s sleight-of-hand.

With an almost magical flourish, Reagan shifted public and media attention from the bloody ruins in Beirut to a tiny island in the Caribbean. Harsh questions about the cause of the Marine massacre evaporated in the press and Congress as Reagan manipulated the perception of events throughout the election year.

Within 48 hours of the Beirut bombing, the president dispatched the first of 5,000 American troops to Grenada. The 422-square mile island was known mainly as an uncrowded spot for divers and the location of an accredited medical school for Americans and others unable to gain admission to such institutions in their own countries.

At the White House, Reagan spokesmen argued that the decision to invade Grenada was justified because of turmoil within the socialist government’s leadership that could threaten U.S. citizens.

Ostensibly, Reagan said he acted to protect 500 Americans, including students at the St. Georges medical school who were under curfew because of the political upheaval. At the same time, U.S. officials explained that Reagan was opposed to the new ties between the governments in Grenada and Cuba, the Soviet Union and China.

Almost 800 Cuban construction workers were building a landing strip which could accommodate Soviet military cargo planes as well as commercial jetliners. According to Reagan, it was nothing less than the vanguard of a major military bastion that would export terrorism and undermine democracy.

“We got there just in time,” Reagan said later.

But the American invasion of Grenada stunned and angered one of Reagan’s closest anti-communist allies, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Grenada was linked to the United Kingdom as a member of the Commonwealth, the residue of the British Empire that stretched around the globe.

The Commonwealth status meant Whitehall was tracking events in St. Georges carefully, including the murder of Prime Minister Maurice Bishop and members of his Marxist-Leninist government by army leaders. In the week before the American invasion, Washington had informed London that there was no need for outside intervention as events were likely to play out without further bloodshed.

The British leader felt betrayed when Reagan, by telephone, informed her of the Grenada invasion after it was underway. Thatcher said Reagan ignored her pleas to reconsider the invasion.

“She (Thatcher) was livid,” said Bernard Ingham, her spokesman.

In Parliament, Thatcher was portrayed as Reagan’s lap dog. Dennis Healey, Labor spokesman on such issues, called the American action, “an unpardonable humiliation of an ally.”

Geoffrey Howe, Britain’s Foreign Minister, was more explicit. “The invasion of Grenada was clearly designed to divert attention,” Howe said in an interview. “You had disaster in Beirut; now triumph in Grenada.”

“Don’t look there, look over here,” Howe said, gesturing with his forefinger.

The shift away from Beirut and to Grenada by the media was intensified by Reagan’s orders to prohibit reporters from witnessing the Grenada invasion. Scrapped were U.S. policies that facilitated coverage of American troops in combat by journalists that had been followed by eight presidents for over 43 years.

Over a five-day period, the Defense Department provided all reports from Grenada, including still photographs and television footage from U.S. Army, Navy and Marine public affairs officers.

When two reporters, including Morris Thompson of Newsday, arrived on the second day of the invasion by rented motorboat, they were quickly arrested and flown to the American command ship, U.S.S. Guam. For two days they were prevented from filing news reports.

Protests by news services network chiefs and newspaper editors resulted in a 15-person media pool spending a few hours on the island under military control before being flown to Barbados on Oct. 27. Four days later, 150 reporters were allowed on Grenada.

But the shooting on Grenada, dubbed Operation Urgent Fury, lasted only a day. While Cuba claimed 50 of its workers were killed, there were no estimates on civilians killed after U.S. Navy fighters accidentally destroyed a mental hospital on the island. American casualties involved two Seal commandos who drowned after being air-dropped into heavy seas and three U.S. Army rangers killed when three Blackhawk helicopters collided while assaulting what turned out to be an empty building.

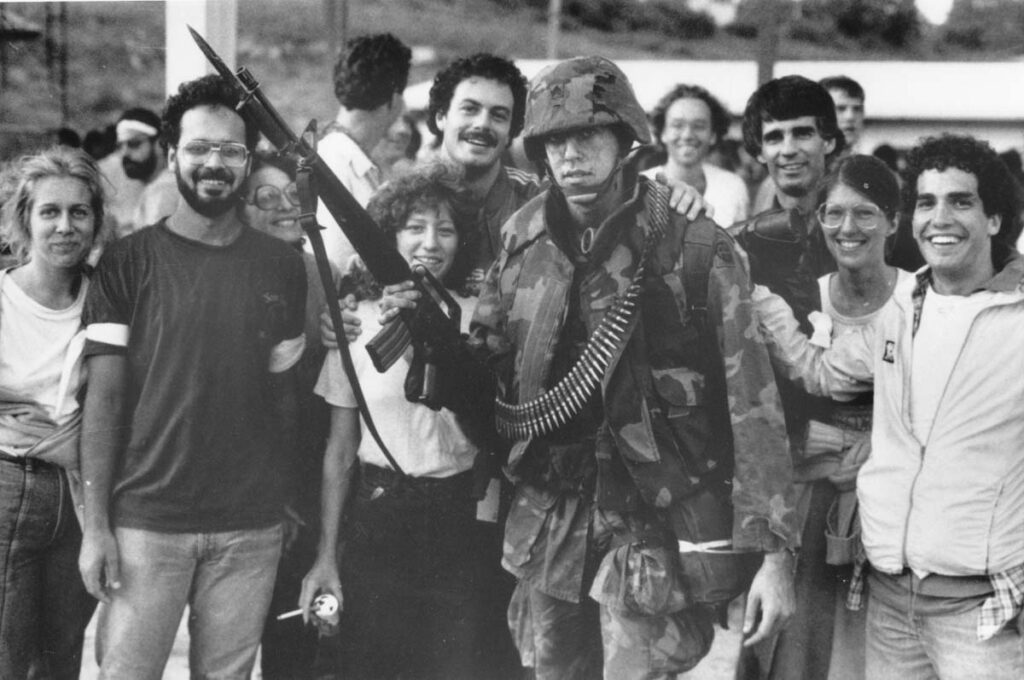

Even so, Grenada proved a brilliant sideshow. Government-supplied pictures of U.S. troops greeting medical school students caused a wave of national pride after the disaster in Beirut. While Reagan dealt with the Marine massacre in an Oct. 27 nationwide television address, he presented both Beirut and Grenada in the context of confronting the Soviet Union.

Syria, backed by 7,000 Russian military advisers, was opposed to U.S. goals in Lebanon, Reagan said. Had he not acted in Grenada, Soviet strategic bombers would soon be operating from the Cuban-built airstrip.

As the television camera moved closer, Reagan recreated a hospital room scene with a Marine commander who visited one of the men wounded in Beirut. The youth was too full of tubes to speak so he scribbled a note: “Semper Fi”—short for the “Semper Fidelis,” the Marine Corp motto of “Always Faithful.”

Reagan concluded by pledging to continue to confront the Kremlin as a way of honoring the men lost in Beirut and Grenada.

“We cannot and will not dishonor them now and the sacrifices they made by failing to remain faithful to the cause of freedom,” Reagan said.

The Grenada invasion along with the speech had a stunning impact on American voters who had disapproved of his foreign policy performance. Voter surveys in The Washington Post in late September showed 50 per cent disapproved and another poll the same month showed Reagan with only a slight lead over potential Democratic presidential contenders.

After the Semper Fi speech, 65 per cent of those surveyed in a Washington Post-ABC News poll supported the Grenada invasion with only 27 per cent opposed. By November, it had risen to 71 per cent approval and Reagan’s lead over potential Democratic opponents jumped to six percentage points.

Even as Reagan was invoking the self-sacrifice of the Leathernecks, the groundwork was being laid in the White House for blaming the Marines for the tragedy in Beirut. Set up to take the fall was one officer crippled by the blast. The president’s defense chief, Weinberger, handpicked members of a special Pentagon commission ordered to investigate the bombing. Headed by retired Navy Adm. Robert Long, the panel was specifically ordered to avoid decisions by the political leadership that led to the Marines being in Beirut.

On Dec. 20, the panel reported that one man should be held accountable for the tragedy: Lt. Col. Howard L. Gerlach, who was in charge of security at the airport base. But Gerlach’s security plan had been approved by Col. Timothy Geraghty, commander of the 24th M.A.U., and the Pentagon commission recommended that both men be disciplined.

However, in an unusual move, President Reagan blocked legal proceedings againts Geraghty and Gerlach and accepted responsibility for the massacre, saying, “The local commanders have already suffered quite enough.” Gerlach was in a coma for several days after the blast, one of more than 50 Marines wounded. He never regained the use of his legs. The President’ s action forestalled almost certain courts-martial for the two officers.

Traditionally, presidents permit military justice to run its course before considering commutation appeals. But general courts martial of Geraghty and Gerlach would have publicized in an election year what the Pentagon commission cryptically called “a series of circumstances beyond the control of these commanders that influenced their judgment and their actions relating to the security of the Marines.”

The evidence suppressed about the massacre leads inside the cocoon spun around the president by his handlers. The Long commission was aware of what took place at the October 18 White House meeting when Weinberger urged Reagan to pull the Marines back aboard ships just offshore. The Long panel also viewed the CIA warnings, including the one three days before the bombing.

Had Reagan given the order that day, the troops could have been evacuated within 24 hours, Marine Corps officers estimated at the time.

For a variety of conflicting and dubious reasons, members of the commission conceded they omitted from their report any discussion of the roles played by Reagan, MacFarlane, Weinberger and other senior officials involved in the tragedy. Panel members agreed to the restriction because they hoped to influence Reagan to withdraw the Marines from Lebanon.

According to one member, the commission worried that revealing all the facts about the internal debate would cause the Administration to reject its call for removal of the still-vulnerable U.S. troops. As it happened, that and other commission recommendations submitted on December 20 were ignored by Reagan. The Marines were finally withdrawn Feb. 7, three months after the bombing.

There was no doubt that Geraghty and Gerlach were negligent for failing to mount more extensive security for the sleeping troops. But the Marine and U.S. Embassy versions of events in the month before the bombing portrayed MacFarlane as issuing combat orders that he said came from, “the Commander-In-Chief.”

Until his arrival in Beirut, the Marines and U.S. Ambassador Dillon were referees of deteriorating relations between Christian Maronite government leaders, and Druse and Shiite factions supported by Syria.

The factional warfare followed Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, a high-risk offensive that destroyed most of Syria’s military forces in an effort to break the hold on Lebanon by Assad in Damascus. Conservative Prime Minister Menachem Begin’s Jewish voters were divided as casualties mounted and Christian allies balked at signing a permanent peace with Jerusalem.

After Israeli troops took part in a massacre of Palestinian refugees in southern Lebanon, Begin ordered a withdrawal of his troops. The withdrawal left the United States, the Marine peacekeeping contingent and Dillon struggling to prevent resumption of civil war in Lebanon.

MacFarlane ordered Dillon to break off mediation efforts. Dillon was pushed aside as MacFarlane made his deputy the senior man in the Beirut U.S. Embassy.

Instead of diplomacy, the ex-Marine wanted to use force. In his first meeting with the wily president of Syria, MacFarlane listened to Assad ramble about the Bermuda Triangle, according to Robert Timberg, in his book on Reagan insiders called, “The Nightingale’s Song.”

“Cosmic phenomena, the influence of extraterrestrial forces on earthly events,” MacFarlane said of listening to Assad. Syria had suffered a massive blow to Soviet-supplied military hardware during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon. To MacFarlane, Syria was vulnerable to American pressure.

“W.C. Fields had a point: ‘You should never kick a man unless he’s down,’” MacFarlane told Timberg. “And, Syria was down and we should have insisted that they get out.”

Lebanese President Amin Geymayel had persuaded MacFarlane that American military intervention could win the day if only the Marines attacked his enemies, the Druse. Dillon later told Congress that MacFarlane was duped into siding with the Christian Maronite leader in what was essentially gang warfare in Lebanon.

American military intervention would signal an end to the Marine peacekeeping mission.

Such combat was banned by Congress under the War Powers Act. MacFarlane skirted the law by winning Reagan’s support for naval gunfire and Marine artillery attacks under the guise of self-defense.

MacFarlane’s dodge, however, was opposed by the boyish looking Marine commander, Col. Geraghty. He argued the Marine deployment at the airport made them vulnerable to bombardment from the nearby Shuf Mountains by Druse and Syrian artillery. Snipers had already been picking off his troops.

“We’ll get slaughtered down here,” Geraghty told MacFarlane during one shouting match that was tape recorded by the Marine base’s telecommunications center. “We’ll pay the price.”

Reagan’s order that MacFarlane could use Marines in combat had been tempered at the Pentagon by Weinberger and the military chiefs.: U.S. firepower could be used but only if the local commander, Geraghty, agreed it would protect his forces.

On Sept. 19, following reports that a tank column was approaching a Christian Marionite stronghold, Geraghty finally gave in to MacFarlane. “To me, they were speaking for the Commander in Chief,” Geraghty later told associates.

At 10:04 A.M. the U.S.S. Virginia opened up with its two 5-inch guns. In Washington the next day, Reagan said in an interview: “I have given orders that the Marines are going to be able to protect themselves. The fighting is aided and abetted by the Syrians who are definitely influenced by the Soviet forces in their country. “

A month later, a grinning driver of a yellow truck drove into the unguarded basement of the makeshift Marine barracks.

Syria was a prime suspect but a strong contender was also Iran which had been inciting an uprising by Lebanese Shiites. About 100 Iranian Revolutionary Guards had, with Syria’s approval, set up operations in Balbek, an ancient Roman city in Lebanon’s Bekka valley.

“We never could be certain if it was Syria or Lebanon,” said Secretary of State George Shultz, of the Marine massacre.

©2002 Patrick J. Sloyan

Patrick Sloyan, a senior reporter for Newsday, is investigating the media and the military.