BUENOS AIRES, Argentina — The first man in the line gave noodles; the woman behind him, a pair of used shoes. Others brought cans of meat and powdered milk, sacks of flour, soup and clothes.

Strange offerings, perhaps, in a traditional Latin American Catholic shrine where candles, flowers and coins usually surround the statue of the patron saint instead of cardboard boxes full of food and clothing. Yet at San Cayetano’s sanctuary in the working-class outskirts of Buenos Aires, most of the worshippers have found greater spiritual meaning in a gift of noodles than a votive candle or money, for all these offerings are sent to the poorest Argentines in rural areas and slums.

One of a growing number of shrines reflecting the “new look” in the Latin American Catholic Church, San Cayetano emphasizes solidarity among Christians and poverty among its religious. It also is one of several pilot projects in the development of “popular religiosity” which Church leaders believe is the key to both a religious and political reformation in Latin America.

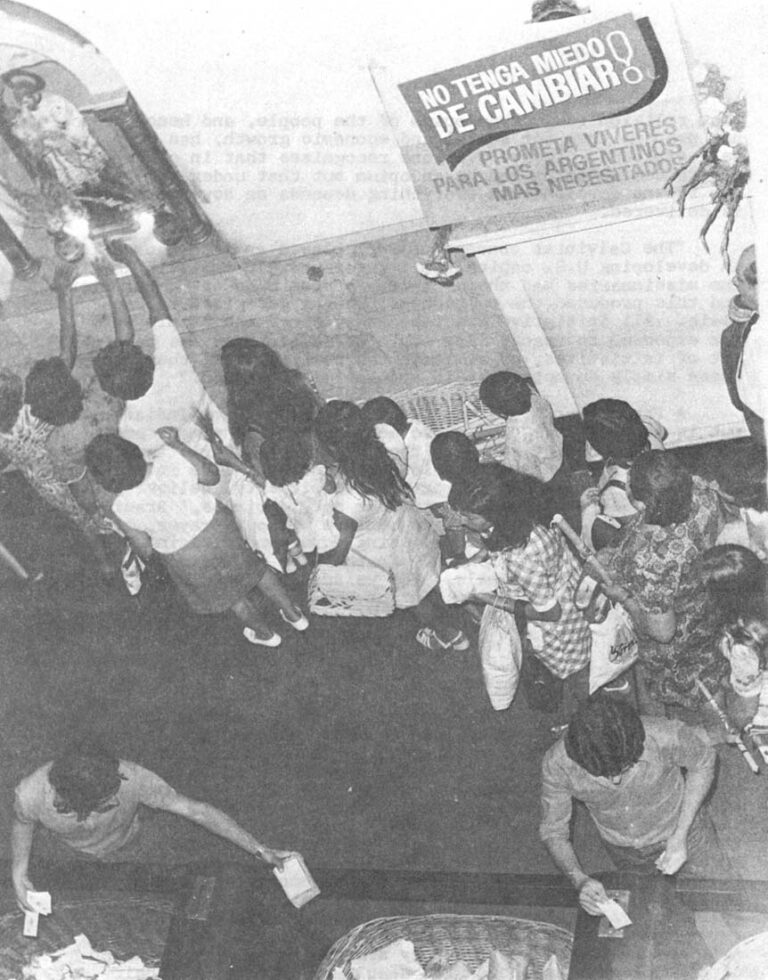

Second in importance only to the sanctuary at Lujan, San Cayetano is visited by a thousand people daily and some 20,000 on weekends who patiently wait for hours to give thanks to or ask help from the Italian immigrants’ saint. Until 1970 when a team of priests led by Father Angel Sallaberremborde assumed the shrine’s administration, the statue was so innundated by peso notes, flowers and candles that no one ever saw it. Through an education program that includes a monthly magazine, Father Angel’s team gradually convinced the people that “they should thank San Cayetano by helping their brothers. Previously it was a closed relationship between the saint and the worshipper. By giving food and clothes, the people are learning that charity is an integral part of faith.”

While most of the people who visit San Cayetano are workers and often poor themselves, their charity produces 15,000 tons of food and 250 bags of clothes each and every month to be sent to the interior provinces. They also finance an employment bureau for peasant girls who come to the city in search of work, a school for housewives and a local branch of Alcoholics Anonymous. Like the eight priests and nuns working with him, Father Angel is desperately poor — and happy to be so. “Every penny given to San Cayetano by the people must be returned to them in food, clothing or services,” he said.

The change in offerings is only one part of Father Angel’s program to get to the roots of a popular religiosity that leads Argentines to San Cayetano but not to Sunday Mass. As the Argentine priest points out, Latin America’s Catholic Church has been “too European, too elitist,” ignoring the rich vein of religiosity in the Latin American cultures. In denigrating such popular cults as San Cayetano, as ignorant or unimportant, the institutional Church alienated vast sectors of the population. Only now with the loss of the youth of the upper classes to Marxism or materialism has the Church harkened back to the mass of the people — the urban and rural poor. To communicate with and evangelize this mass, however, the Church has had to learn the language and symbols of the people, hence the new interest in Latin America’s highly varied expressions of popular religiosity. The first commandment in religious circles today is to listen and observe instead of “imposing foreign ideas on the people,” said Father Angel.

In the flood of literature now pouring forth on the subject, there is a common theme of humility and regret, for in studying popular religiosity Church intellectuals have discovered how blind they were to the depth of the people’s simple faith. “While 90 percent of Latin Americans are baptized Catholics, only 20 percent regularly attend Mass,” said a Colombian priest. “This does not mean that the remaining 70 percent are not Christians, however. It means that we priests have not known how, or bothered, to bring these people into the community of the Church.”

What is more, says Brazilian theologian Eduardo Hoornaert, the Church must share part of the historical blame for the poverty of millions of Latin Americans because European missionaries helped create the psychological conditions for fatalism by destroying the indigenous people’s culture and imposing the religion of the Spanish conquerors upon them. “Sociologists are beginning to see a definite connection between development and religion,” explained Hoornaert. “The thesis of Marx and Engels that religion is just an opium of the people, and hence does not prepare them for social and economic growth, has been pretty well exploded. Today, everyone recognizes that in certain circumstances religion can be an opium but that under others it can foment development: everything depends on how the message is delivered.

“The Calvinist concept of work played an important role in developing U.S. capitalism. Unfortunately in Latin America the missionaries had the mentality of the conquering colonists, and this produced the culture of poverty described by Oscar Lewis. All initiative was taken away since the people were not expected to react. Any ethic of development has to grow out of initiatives, or at least the possibility of them, and these simply do not exist in a colonial situation.”

A Paraguayan “pai,” or priest of the Guarani Indians put it another way: “The white men who call us pagans are themselves unChristian. For them, I am not a Christian because I have my ritual dances and long orations and live in a community without social elasses or private property, believing that we are all sons of God, baptized or not, ‘gringos,’ Brazilians or Paraguayans. But the white men are without prayer, egotistical, violent and deceitful, using force and disdain to make us afraid and to diminish us. In the name of their religion they treat us like animals. Yet we are the true inhabitants of this land, the favorite sons of the Great Grandfather, and we know there is a place for all of us in the heavens that He created.”

Unable to express themselves in the language of the conquerors, Indian and African slaves “reinvented” religion, as Jesuit anthropologist Bartomeu Melia describes it. In Paraguay, for example, Christian Guaranies find religious expression in the repetitive chanting of litanies, such as the rosary and funeral orations. “What is said is less important than how and why it is said,” Melia explained. Likewise, the religious pilgrimage is more important than arrival at, or presence in, the sanctuary or attendance at Mass. (This is true in other Latin American countries such as Argentina and Chile, where the sacrifice inherent in a pilgrimage has more spiritual value than attendance at shrine ceremonies.) Gestures, symbols and legends are extremely important in Latin American religiosity since they are the means of expression of a people who are otherwise unable to communicate their feelings.

The racial fusion of black, Indian and white cultures also produced a variety of syncretic religions. Latin American colonial art is rich in examples of this fusion, such as the use of moon and sun in religious paintings to represent the creator and his wife/mother,or the Bolivian Indians’ golden-haired Virgins with one breast longer than the other, symbolizing the Aymaras’ earth mother.

Mexico’s Otomies Indians, who devote a great deal of time to praying to the dead, are less concerned about the dead’s spiritual comfort than their attempts to infect the living with disease. Only with long prayer rituals, a Spanish version of the pre-Columbian “ndajana” ceremony, can they liberate themselves from these spirits.

To judge by the vast number of crosses in southern Mexico, the Zenacantecos Indians are exceptionally Christian. But in the Zenacantecos’ concept the cross simply represents a meeting place where ancestral gods gather to debate the affairs of their living descendents, from whom they expect offerings of black chickens, white candles and aguardiente, the local firewater.

Even baptism, which is the most universally accepted sacrament in Latin America, has other meanings for the people. Among the Indian tribes in the Andes Mts., baptism is an insurance against thunder-bolts. For the Zenacantecos it is a means of attaching the soul to the body. And in Paraguay baptism prevents the child’s head from growing too large.

As Hoonaert points out, the Indians and the Africans soon concluded that Christianity and their religion “were not so different after all because of the readiness with which the white men’s priests baptized their children.” Thus Catholicism gradually came to be regarded as a “magnificent expansion of their own fetishisms.”‘ The plasticity and superficiality of the early missionaries’ Catholicism actually made it more acceptable to Brazilian blacks than the Islamic religion. As in Haitian voodoo, Brazilian macumba transposed the characteristics of the Christian saints onto the African “orixas,” or minor deities. Hence Xango became St. Jerome and Abaluae, St. Lazarus, while Oxala is Jesus Christ.

In the Umbanda religion, the rituals of which are known as macumba, there is no discrimination between Christian and African saints although there is a hierarchy of greater and lesser spirits, the latter including “caboclos” representing the original Indians and the “pretos velhos,” a Brazilian version of Uncle Tom.

So popular is Umbanda that it has 32,000 centers, or “terreiros,” in Rio de Janeiro alone. Catholic sources estimate that 30 percent of the Brazilian population practices Umbanda, and this does not include Brazil’s other great African cult, the Candomble religion of Bahia. In Rio the Umbandistas are grouped into four federations which regularly elect middle-class deputies to the local assembly although Umbanda, like the samba, belongs to the counterculture of the Rio slums.

Government officials are delighted at Umbanda’s growth because unlike the Catholic Church, which is highly critical of the military regime, Umbanda preaches an authoritarian government and insists on a rigid hierarchy. “You never hear any talk of politics or ‘liberation’ in an Umbanda terreiro,” said an Umbanda priest.

Umbanda and Candomble are not the only challengers to Catholic hegemony in Brazil. The Protestants also are making sizeable inroads although they are not the main-line, middle-class denominations but the Pentecostals, who account for 75 percent of Brazil’s eight million Protestants. Like Umbanda, the Pentecostal religion abjures political involvement, taking an other-worldly approach. Its particular attractions for Latin Americans are its emphasis on the layman instead of a priestly hierarchy and the opportunity for self-expression.

As a result of the new interest in popular religiosity, the Catholic Church is paying closer attention to the African cults and to the Pentecostals in order to learn the causes of their success. One result has been more participation by laymen in the Church, including a largely lay-directed Mass. Catholic religious also are attempting to reach some sort of ecumenical understanding with Umbanda and Candomble priests. Father Francisco Barturen, who runs a fishing cooperative in Bahia, claims the basis of the cooperative’s success was his participation in annual Candomble fishing rites. “The fishermen told me that if I, a Catholic priest, could join in their rites, than I must really understand them,” he said.

While advocating popular religiosity, the Catholic Church is not blind to its defects, the worst of which is fatalism. Because God is viewed as some remote, powerful Being, most Latin American Catholics turn to the saints or souls of the dead to intervene for them. There is a saint for almost every activity, from lottery ticket selling to bread making, and for every conceivable problem. St. Patrick, for example, cures snake bites while St. Anthony is invoked to attract boy friends. Each country also has its own unofficial saint such as Venezuela’s Maria Leonza, an Indian princess who doubles as earth mother and goddess of the Caracas freeways; Jose Gregorio Hernandez, a Venezuelan doctor much revered by the Colombians and Venezuelans; and Argentina’s “Dead Correa,” a young mother who died of thirst in the deserts of western Argentina around the year 1835.

The saints and souls of the dead are as real to these people as their own neighbors. In a typical scene at a recent Aymara religious festival for St. James in Bolivia, for example, a mourning Indian woman harangued the effigy and even struck it to elicit a response. Malnutrition and lack of medicine were not responsible for her baby’s death. It was the saint’s fault. Likewise, any sudden improvement in the Latin American family’s fortunes is attributed to offerings or promises made to a particular saint or soul. (Latin American highways are littered with crosses and miniature chapels to the souls of the dead called “animitas,” some of which, such as the “animita” in the central train station in Santiago, Chile, are believed to have miraculous powers.)

The principal drawback with this personal you-me relationship with the saint or “animita” is that it induces a narrow, fatalistic view of life. Church studies in the Santiago slum of La Vitoria, for example, show that the people believe they will always be poor because that is their destiny. There in no happiness in the afterlife either since dead souls spend their time haunting the living, a concept similar to that of Mexico’s Otomies Indians. “Religiosity/animism is basically something that helps the person to get through this life,” said Chilean theologian Antonio Bentue, the author of the study. “The person at least has the possibility of offering the saints or souls a gift to intercede.”

In this very narrow relationship, there is no possibility of any change “because authority and tradition are accepted without criticism,” he said. “Nor is there any social conscience within the community. If there were, the people would join together to protest the economic and social realities responsible for their poverty instead of trying to bribe God through the saints or the souls of the dead.”

For all this, there are a number of positive values in popular religiosity such as a deep sense of the sacred and a disposition to prayer, spontaneity, courage, cordiality and a willingness to share in happiness and suffering.

The challenge, according to Latin American bishops, is to encourage the people to see the saints as models of Christ’s life instead of interceders and to alter the fatalistic aspect of devotions by educating the people “to become co-creators with God.”

This is easier said than done, however, because nobody yet has sufficient knowledge of popular religiosity to suggest precise teaching tools. The only generally accepted conclusion to date is that popular religiosity must not be denigrated. Joaquin Alliende, a Chilean priest who is one of the most eloquent spokesmen for popular religiosity in Latin America, cites the actions of the bishop of Buga, Colombia, as a typical example of what not to do. The more the bishop tried to eradicate the legend surrounding the Buga shrine of Our Lord of Miracles, the more he alienated the people, Alliende said.

“There is a popular wisdom in all these legends,” he added. “In this case it was the story of an Indian woman who worked all her life to save enough money to buy a crucifix, but just when she had enough money her neighbor took seriously ill. It was a hard decision, but she gave her savings to the neighbor to buy medicine. When she returned to her home, crying over her loss, she found a beautiful crucifix had miraculously appeared, a gift from God.

“It doesn’t matter whether the Indian woman ever existed. What is important is the message of faith and charity in the legend, and that should receive maximum dissemination.”

Though new, popular religiosity is the hottest issue in the Latin American Church. This is in part because everybody can agree that it is a good thing, unlike Christian dialogue with Marxists, which split the Church in the 1960s. It also is seen as “one last chance for the Church to evangelize the masses.”

The Church may never have a better opportunity because the upsurge of interest in popular religiosity has coincided with two other important events — the exodus of priests and nuns to impoverished rural areas and slums and the rise of military dictatorships in 11 Latin American countries. As a result of military repression, the hierarchy in many countries has taken a firm stand against dictatorship in favor of the poor. At the same time, it has begun to see the seeds of a new kind of society in popular religiosity which, if purified, fortified and transformed by the people with the Church’s help, can overcome the insecurity and anxiety which Catholic sociologists say are at the root of fatalism and poverty.

Though sneered at by many European intellectuals, popular religiosity is a genuine form of cultural expression and creativity — indeed the only one for most Latin Americans. “If popular religiosity can be encouraged and developed, it may lead to other expressions of the people’s feelings in politics and social affairs,” said an Uruguayan theologian. “We believe that it is the foundation of a future social conscience.”

Young and old religious agree that the Latin American Church has been too much under the influence of French and Belgian theologians and that it is time to “deintellectualize the Church.”

“Otherwise,” warned Father Alliende, “we may find we are strangers in our own land,”

Nowadays, very few Latin American seminarists travel to Europe to complete their studies since such institutions as Rome’s Pio Latino Americano and Pio Brasileiro colleges are held responsible for the Church’s alienation in Latin America. Father Jose Ayestaran, Pio Latino’s rector, foresees a time when the college will no longer have any Latin American applicants (the Latin American enrollment has dropped from 100 to 13 in only six years). “The young Latin Americans say they want to stay home and study their own people,” he said.

Such is the interest in popular religiosity that most of the local churches have sponsored conferences on the subject while the Chilean hierarchy has even opened a seminary on popular religiosity. Meanwhile, the Argentines are rewriting the Bible in Argentine Spanish, the Paraguayans are developing new forms of religious instruction based on Guarani Indian traditions, and in Brazil lay ministers of the sacraments are increasing so fast that they may soon outnumber priests.

Nowhere is the impetus greater than in Chile, where the Church has undertaken a complete revision of ceremonies and educational programs in order to incorporate popular traditions and conceptions. Traditional taboos have been swept aside, such as dancing in front of the altar during Mass. At such religious dance festivals as Le Tirana in northern Chile, the people are encouraged to join in the Mass instead of holding their dances away from the Church as occurred in the past. Sixteenth century in origin, these dances are a deep expression of reverence for La Tirana’s Virgin of Carmen with over 45,000 participants. Nowadays, there are more religious dance groups in northern Chile than sports clubs, and they practice two hours daily, five days a week during four months of every year, all in honor of the Virgin.

Once disdained as “illiterate cowboys,” Chile’s colorful “huasos” are urged to attend the annual festival of “Cuasimodo” at the national shrine at Maipu, where Cardinal Raul Silva, dressed in a cowboy poncho, welcomes 2,000 “huasos” on horseback and bicycles to reenact the ancient tradition of accompanying the priest on his rounds as he distributes communion to the sick. Mass is later celebrated with dancing and folk singing. This is not a once-a-year event as the “huasos” and their families continue to meet with Maipu’s pastoral group throughout the year in an effort to deepen their faith.

Another Chilean tradition, the singing of popular poetry, has been rediscovered by the Church which is incorporating some of the thousands of songs inspired by the Old and New Testaments into Church hymns. Often composed by illiterate peasants, these “creole psalms” reflect a deep piety and folk wisdom that offer a far better catechism than traditional school texts.

As in most of Latin America, the Chilean Church has found its best emissary in the Virgin Mary, whom Chileans affectionately call “Little Mama” and address with the familiar Spanish form of “tu.” The Virgin of Carmen is particularly revered as she was the “great general and patroness” of the Chilean armies during the wars of independence. As a popular song to the Virgin of Carmen notes, “She sews irons, cleans, sweats. She is a ‘chinita’ (peasant girl) just like you.”

To revive the popularity of the Maipu sanctuary, considered a white elephant only a decade ago, Father Alliende, then rector of Maipu, took the sanctuary’s statue of the Virgin of Carmen on a pilgrimage through 66 Chilean cities and towns in 1968. The result was overwhelming, with some 100,000 people attending the annual 10-mi. procession from Santiago to Maipu, the largest concentration of people in Chilean history.

Another result of Alliende’s travels was a superb statue of the Virgin carved by the inhabitants of Easter Island, a Chilean possession, that looks very much like the island’s ancient Maori carvings that have bewildered archeologists and anthropologists for decades.

“The islanders were disappointed when we arrived without the statue of the Virgin of Carmen,” recalled Alliende, “but we explained to them that she was Western and white and that they should make their own Polynesian Virgin because Christ and the Virgin were not Italians or Europeans and that all people had made images of them according to their cultural characteristics.”

While the islanders have a tradition of counterpoint singing in Church, they had never attempted any religious carving or painting. After an election to decide the island’s 10 best artisans, the people selected one of the rare trees that grow in the sacred grounds of the Maoris to make the Virgin and Baby Jesus. Standing on a map of the island, the Virgin now looks to sea in the fishermen’s harbor from black stone eyes in a long Romanish face, just like those of the islanders’ statues, with a crown of sea shells on her head.

During the religious ceremonies that took place before, during and after the carving, people forgot old feuds over stolen fishing nets or boats to become friends again. To climax the ceremony on the day of the Virgin’s arrival at the harbor, an out-of-season swallow appeared in the sky, a symbol of happiness and the Holy Spirit.

The Virgin of Carmen also has unlocked any number of closed doors in the Santiago slums where personalized letters from the Virgin and home visits by lay missionaries for Mary have brought thousands of people back to the community of the Church.

Many are surprised at the altered atmosphere with its emphasis on laymen, Christian solidarity and religious gestures such as raising arms to heaven or embracing everyone in the Church. “Speak up,” exhorts one of a series of comic books produced by the Church for the slums. “Get to know your neighbor in Church; ask his name. The Church is not a supermarket for the sale of sacraments. We are all part of the same family and must feel responsibility for that family. Praying all the time won’t help much if Christians don’t assume responsibility for the difficulties of the people, just as Jesus did.”

If Chileans ever doubted the Church’s own cnmmitment to its words, there can be no question today. The only institution capable of opposing the country’s military regime, the Chilean Church has not hesitated to assume the responsibility of defending the poor and the politically oppressed, thus earning more prestige than it has known in over a century — and more repression. Everywhere Cardinal Silva goes, crowds of clapping people appear to shout, “Viva el Cardinal.”

Such is the power of the Church and the Virgin of Carmen that the military refused permission for the annual procession to Maipu last year for fear that it would turn into a giant religious-political rally. Instead, a quiet, select ceremony was proposed in which the military intended to deposit a steel torch in the shrine in everlasting memory of the armed forces. Pointing out that the Virgin belongs to all Chileans, not just the generals, the Chilean hierarchy declined. In any case, Church surveys had shown that the people do not want a warlike Virgin such as the “Star of the Armed Forces” but a humble, hard-working “chinita” just like them.

Received in New York on December 13, 1976

©1976 Penny Lernoux

Penny Lernoux, freelance writer and Latin American correspondent for The Nation, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner with support from the Rockefeller Foundation. Her subject is the theological, political, and sociological impact of the revolution in the Roman Catholic Church in Latin America. This article may be published with credit to The Nation, to Miss Lernoux as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation, and to the Rockefeller Foundation. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of either Foundation.