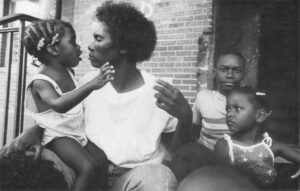

For the past several years, advocates for the homeless have sought public support by drawing attention to the number of homeless families on the streets. That is an understandable tactic, for Americans respond to social issues on the basis of sympathy for the “innocent” or “deserving”– those whose blamelessness touches the heart and who we deem unable to care for themselves. Families, and women with children, obviously fill this bill.

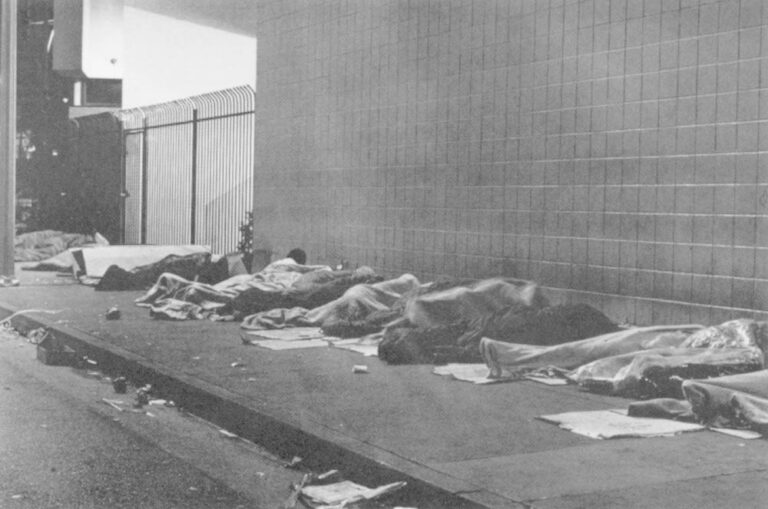

But the fact remains, beyond propaganda, that the problem of homelessness is essentially a problem of single adult men. Far more men than women, and far more single adults than families, end up homeless. Until we understand how and why that happens, nothing we try to do about homelessness will have much of an impact.

Most figures pertaining to the homeless come from limited studies or educated guesses which dissolve, when examined, in one’s hand. The most convincing statistics I know can be found in James Wright’s small book, Address Unknown, The Homeless in America. According to Wright, out of every 1,000 homeless people in America, 100 or so are adults with children, another 100 are the children themselves, and the rest will be single adults. Out of that total, 150 will be single women, and 650 will be single men. Break that down into percentages. Out of all single homeless adults, 80% are men; out of all homeless adults, 70% are single men; out of all homeless people–adults or children–fully 65% are single men.

Even these figures do not give the full story. Our federal welfare system aids mainly women with children and, on occasion, intact families. That means most of the families on the streets have either fallen through cracks in the welfare system or not yet entered it. They will, in the end, have access to some sort of shelter and aid, while it is the single adults who will be left permanently on their own.

I do not mean to diminish the suffering of families, nor to suggest that welfare usually is anything more than a form of indentured pauperism so grim it shames the nation. But it does, in fact, get families off the streets, and that leaves behind, as the long-term homeless, the chronically homeless, single adults, four-fifths of whom are men. Seen that way, homelessness emerges as a problem usually involving what happens to men without money, or men in trouble.

Why do so many more men than women end up on the streets? First, the simplest answers.

Life on the streets, as dangerous as it is for men, is even more dangerous for women, who are far more vulnerable. While many men in trouble drift almost naturally onto the streets, women do anything they can to avoid it.

Second, there are proportionally far more private and public shelters and services available to women.

Third, women are accustomed to asking for help while men are not, and women make better use of available resources.

Fourth, poor families in economic extremis seem to practice a form of triage. Men are released into the streets more readily, while women are kept at home even in the worst of circumstances.

Fifth, there are cultural and perhaps genetic factors at work. There is some evidence that men–especially in adolescence–are more aggressive and openly rebellious than women and harder to socialize. Or it may be that men are allowed to live out impulses that women are taught to suppress, and they therefore end up more often in trouble.

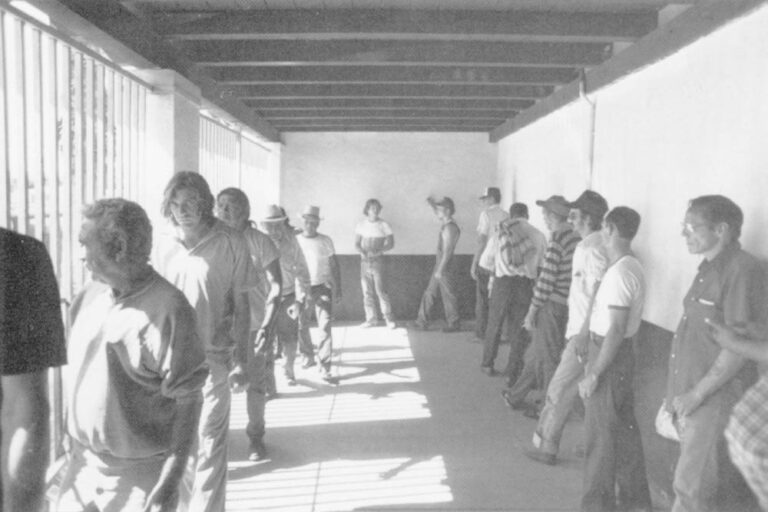

More important, still, may be the question of work. Traditionally, the kinds of work associated with transient or marginal life have been reserved for men. They brought in crops, worked on ships and docks, built roads and railroads, logged and mined. Such labor granted them a place in the economy while allowing them to remain on society’s edges–an option rarely available to women save through prostitution.

And society always has seemed to intentionally produce the men for this work. Obviously, poverty and joblessness forced men into marginality, but there was more to it than that. Schools produced failures and drop-outs; family life produced runaways and throwaways; wars rendered men incapable of settled life; small-town boredom led them to look elsewhere for larger worlds.

Now, of course, the nature of work has changed and society has little need for such men. But like a mad engine that cannot be shut down, society goes right on producing them. Its institutions function as they always did: the schools hum, the families collapse, the wars churn out their victims. But what is there for them to do? The low-paying service-sector jobs that have replaced manual labor go mainly to women and docile high-school kids, not to the men who once did the nation’s roughest work.

And remember here, too, in terms of work, that women, especially when young, have one final option denied to men. They can take on the “labor” of being wives or companions to men or of bearing children, and in return they will often be supported, or taken care of by somebody else.

I know: such roles can constitute a form of oppression, particularly assumed out of necessity. But nonetheless, the possibility is there: It is permissible for women to avoid disaster by becoming financially dependent on others, while such dependence is more or less forbidden for men.

Finally, there is the federal welfare system. I do not think most Americans know how the system works, or how for decades it has actually sent men into the streets, creating male homelessness at the same time it aids women and children.

There are two main programs which provide for Americans in trouble. One is Social Security Insurance, known as SSI. It goes to men and women who clearly are unable for physical or mental reasons to care for themselves. The other is Aid to Families With Dependent Children, or AFDC. It is what we ordinarily call “welfare.” Begun early in the century and then expanded and refined during the 1930’s and again in the 1960’s, it has always been a program meant mainly for women and children and was therefore limited to households headed by women. As long as an adult male remained in the household as husband or father, no aid was forthcoming. Changes in the system last year have modified this somewhat, and males can now be present if they satisfy certain federal guidelines pertaining to work history. But in poor areas and among certain ethnic groups where unemployment runs high, such changes mean little, and the effects of this policy on men remain as devastating as ever.

When it comes to “able-bodied” (and employable) single adults, there is no federal aid whatsoever. Individual states and localities sometimes provide their own aid. But this is usually granted only on a temporary basis or in emergencies. And in those few places were it is available for longer periods, it is almost always so niggardly, so ringed with capricious requirements, that it is of little use to most of those in need.

This combination of approaches not only systematically denies to men any aid as family members or single adults, it means that the aid given to most women deprives men of homes. Given the choice between receiving aid or living with broke or jobless men, what do you think most women with children do? The regulations force men to compete with the state for women. As a woman in New Orleans once told me: “Welfare changes love. If a man don’t make more than I get from welfare, I ain’t gonna look at him. I can’t afford it.”

Everywhere in America, money-less men have become ghost-lovers, ghost-fathers, one step ahead of welfare workers they fear will disqualify others for having a male around. In many ghettos or housing projects throughout the nation you now find women and children in their deteriorating welfare apartments, and their companions and fathers in even worse condition on the streets: in gutted apartments and junked cars, denied even the minimal help given the opposite sex.

Is it surprising in this context that many African-Americans see welfare as an extension of slavery that destroys families, isolates women and humiliates men? Or is it accidental that in many poor communities, family structure collapses and more than half the children are born outside marriage at precisely the same time that disenfranchised men are flooding the streets? I do not think so. Before judging men and their failures, one must understand that their social roles are in no way sustained by the institutions and policies that in small ways make female roles sustainable.

Is this merely an accidental glitch in the system, something that has happened unnoticed?

Again, I do not think so. Something else is at work here: deep-seated prejudices and attitudes towards men that are so pervasive, so pandemic, so much a part of culture, that we have ceased to notice or examine them.

To put it simply: men are neither supposed nor allowed to be dependent. They are expected to take care of others and themselves. And when they cannot or will not do it, then the assumption at the heart of the culture is that they are somehow less than men and therefore unworthy of help. An irony asserts itself: by being in need of help, men forfeit the right to it.

Think here of the phrase “helpless as a woman.” This demeans women. But it also does violence to men. It implies that a man cannot be helpless and still be a man, or that helplessness is not a male attribute, or that a woman can be helpless through no fault of her own. But if a man is helpless, it is, or must be, his fault.

Try something here. Imagine walking down a street and passing a group of homeless women. Do we not see them spontaneously as victims, and wonder what has befallen them? Do we not see them as unfortunate and deserving of help and want to help them?

Now imagine a group of homeless men. Is our reaction the same? Is it as sympathetic? Or is it subtly different? Do we have the same impulse to help and protect? Or do we not wonder, instead of what befell them, how they have gotten themselves where they are?

Then, too, there is our fear. When we see homeless or idle men we invariably sense or imagine danger–as if, beyond the pale, they are also beyond social control and therefore are to be avoided or suppressed rather than helped. Here, too, work plays a role. In his memoirs, Hamlin Garland describes the transient farm-workers who passed through his childhood village each year at harvest-time. In good years, when there were crops to bring in, the men were welcomed: housed and fed. But in bad years, when they weren’t needed, they were forced to stay outside of town or to pass on unaided; they were seen, then, as threats to peace and order, barbarians at the gates.

The same attitude is with us still. When men work (or when they go to war–work’s most brutal form), we grant them a right to exist. But when work is scarce, or when men are of no economic use, then they become in our eyes not only superfluous, but also a danger. We feel compelled to exile them, to drive them away to shift for themselves in more or less the same way that the Puritans, in their city on a hill, treated sinners and rebels.

One wonders how far back such attitudes go. One thinks of the Bible and the first disobedience in the garden, when women were cursed with child-birth and men with labor–the destinies still assigned by the welfare system and our private attitudes.

Or one thinks of the Victorian era when the idealized vision of women and children had its modern beginnings. They were set outside the industrial nexus and freed from heavy labor while being rendered more dependent and subservient to males than ever. It was a process that in many ways diminished women, but it had a parallel effect on men. It defined them as laborers and little else, especially if they came from the lower classes. The yoke of labor lifted from the shoulders of women settled even more heavily on the backs of men, categorizing them in ways as narrow and as oppressive as those to which women were confined.

We are so used to thinking of ours as a male-dominated society that we lose track of the ways in which some men are perhaps more oppressed than most women. But race and class, as well as gender, play roles in oppression. And while it is true, in general, that men dominate both society and women, in practice is it only certain men who are dominant. Others, usually those from the working class and often darker-skinned, suffer endlessly from forms of isolation and contempt which exceed what many women experience.

The irony at work is that what you find among homeless men, and what lies at the heart of their troubles, is precisely what our cultural myths deny them: a helplessness they cannot overcome on their own. You find a vulnerability, and senses of injury and betrayal, and a despair equal to what we accept without question in women.

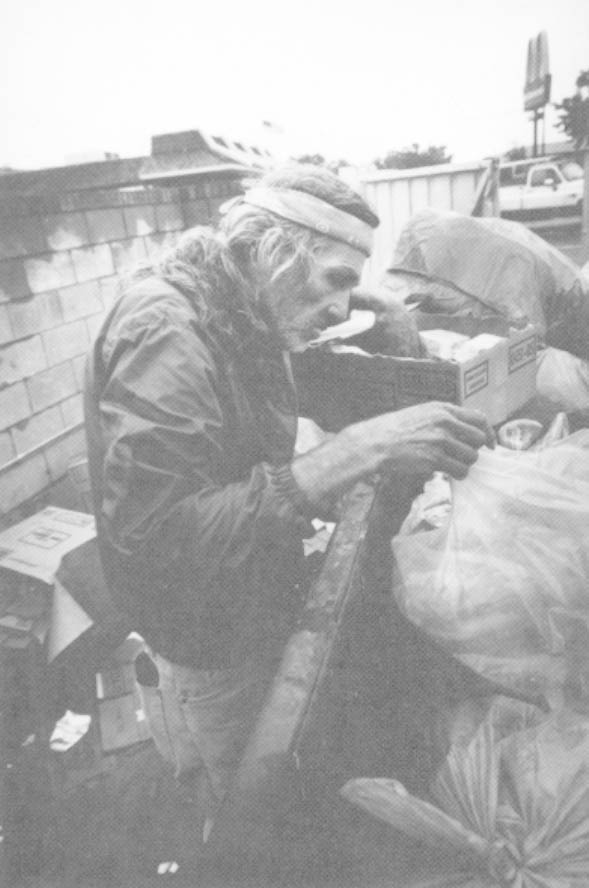

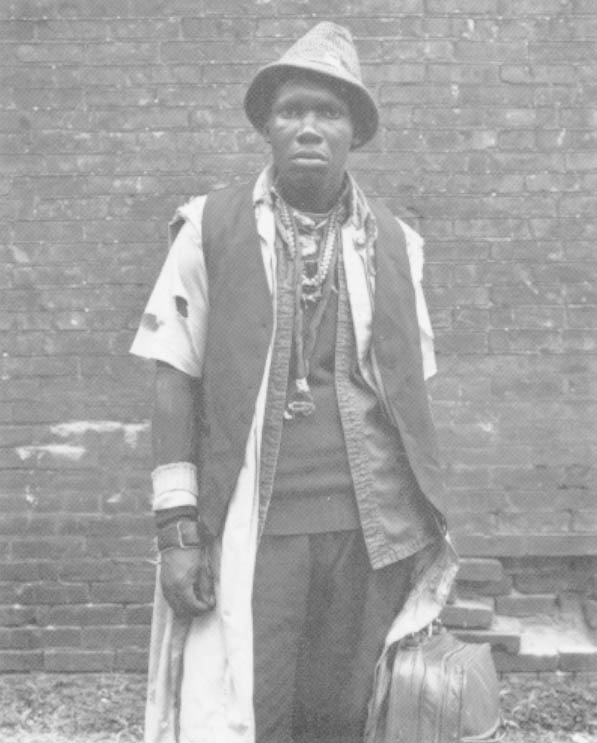

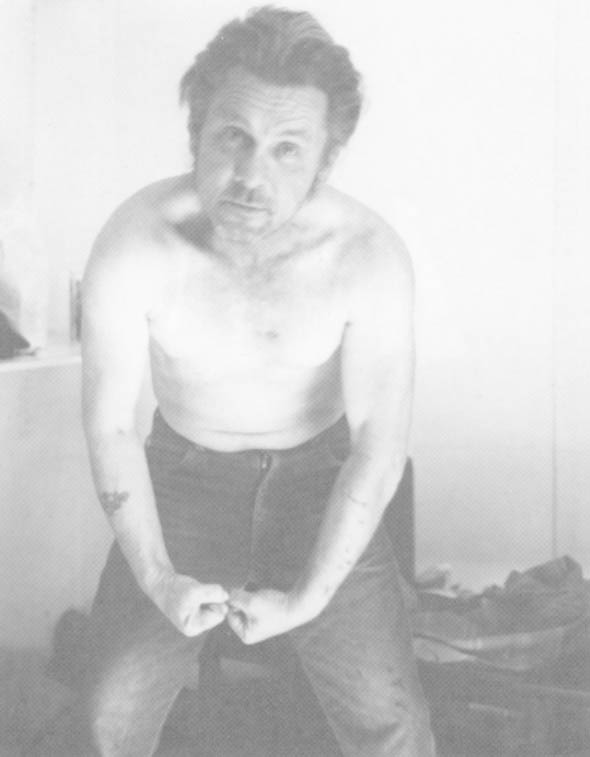

Often this goes unadmitted. I remember several men I knew in a California hobo jungle. Most of them were vets. They had constructed a tiny village among the trees, and when smoke filled the clearing and they stood around bare to the waist, you would swear you were in an army jungle camp in Vietnam. They drank throughout the day and at dusk there always came a moment when they wandered off individually to stare out at the mountains or sea. You could see on their faces at such moments, if you caught them unawares, a particular and unforgettable look: pensive, troubled, somehow innocent–the look of lost children or abandoned men.

It is a look you see over and over among homeless men. It tells a story not often put into words, about how they have been injured in some fashion or suffered a kind of wound, often in childhood, from which they have never recovered.

I remember, too, a young man in my town who always was in trouble for beating up older drunken men. No one understood his brutality until he explained it one day to a young woman he trusted:

“When I was a kid my daddy ran off and my mother’s drunken brothers raised me. Whenever I made a mistake they punished me by slicing my legs with a straight razor.”

He pulled up his pant-legs to reveal on each shin a ladder of scars marking each childhood error.

This can stand for countless stories I’ve heard. The feeling you get again and again is that most men on the street have been orphaned in some way, deprived somewhere along the line of whatever kinds of connection, support and sustenance are required if people are to find and keep places in the social order.

Of course, economics plays a part in this. But more often than not, something else is at work. For decades now, sociologists have pointed to rents in our private social fabric as well as our public safety nets and to those they injure: abused kids, battered women, isolated adults, and alcoholics and addicts.

Why is it so hard to us to see homeless men in this context? Why do we find it difficult to see that grown men, as well as women, can be damaged by childhood, or that they often end up on the edges of society, unable to play expected roles?

Do not forget the greatest violence done to men: the tyrannous demands made upon them when young by older and more powerful males: that they kill and die in war. Long before the war in Vietnam had crowded our streets with vets, almost half the men on America’s skid rows had seen service in one war or another–a much higher percentage than in the regular population. Many men never recover fully from war, having seen too much of death to ever again do much with life.

Nor is war the only form in which death or disaster have altered the lives of homeless men. Listening to their stories one is constantly reminded that all of us remain vulnerable, even now, to the furies and fates which the Greeks believed stalk all human lives.

Gene, a homeless man I know, was conceived when his mother slept with his father’s best friend. Neither of his parents wanted him, so he was raised by his mother’s parents, who saw him only as the living evidence of her disgrace. When I first met him, he was living in a cave. He spent the money he earned at odd jobs on dope and his friends. Then he met a woman and they moved to a cheap hotel. She got pregnant; they planned to marry, but then they argued and she ran off and either had an abortion or miscarried–it was never clear. When Gene heard about it, he took to his bed for two weeks and would not sleep, eat or speak. When I later asked him why he said:

“I couldn’t stand it. I wanted to die. I was the baby she killed. It was happening all over again, that bad stuff when I was a kid.”

Not everything you hear on the streets is so dramatic. Often it is simply “normal” life which proves too much for men. Some have merely failed at or fled their assigned roles: worker, father, husband. Some never had a chance, having lacked whatever it takes to please a boss or woman. Some decided it wasn’t worth the trouble to learn how to do it. Not all of them are “good” men. Some have left women and children in the lurch when responsibility or stress were more than they could handle. “Couldn’t hack it,” they’ll say, or “I had to get out.” Still others were themselves abandoned by women they mistreated or disappointed.

Are such men irresponsible? Perhaps. But working with homeless men over the years I’ve seen how many of them are genuinely unable to handle situations others manage with ease. It is as if their defenses and even their skins are so much thinner than in the rest of us that they give way as soon as trouble or stress or too many demands appear. Is that surprising? The curious world we’ve compounded in America of equal parts of freedom and isolation and individualism and demands for obedience and submission is a strange and exhausting mix, and no one should be startled by the number of victims and recalcitrants it produces or that they lose their way.

Finally, whatever particular griefs men may have experienced on their way to homelessness, there is one last, devastating kind of sorrow all of them share: their sense of betrayal at society’s refusal to recognize their need. Most of us–both men as well as women–grow up expecting, deep in our hearts, that when things go terribly wrong someone, from somewhere, will step forward to help us. That this does not happen, that all watch indifferently from the shore as each of us, in isolation, struggles to swim and then sinks, is perhaps the most terrible discovery that anyone in any society can make. When troubled men realize this, as they all do sooner or later, then hope vanishes completely. Despair rings them round; they become what they need not have been: the homeless men we see everywhere around us.

What can be done about it? What will set it right? One can talk about confronting and changing the root causes of marginalization: families, schools, communities (or their absence), the stupidities of war, the cruelties of racism and discrimination and economic inequities, the failure of reciprocity among us. But what good will that do? America is what it is, and though it is easy to call for major kinds of renewal, nothing of the sort is likely to occur.

That leaves us with ameliorative and practical measures, and it will do no harm to mention them, though they, too, are not likely to be tried: a further reformation of the welfare system; the federalization of assistance to single adults; changes in the amount and duration of unemployment insurances; further raises in the minimum wage: expanded benefits for vets; job training; detox centers; low-cost hotels and boarding houses designed specifically for transient men; finally, the contemporary versions of the Depression programs–the WPA, the CCC–that offered jobs for men at the same time welfare was being supplied to women.

But beyond all this, and behind and beneath it, there remains the problem with which we began: the prejudices at work in society and which prevent even the attempt to provide solutions. Suggestions such as those I have made will remain merely utopian notions without an examination and renovation of our attitudes towards men. Over the past several years we have slowly, laboriously, begun to confront our prejudices and oppressive practices in relation to women. Unless we now undertake the same kind of project in relation to men in general and homeless men in particular, nothing whatever is going to change. That’s as sure as death and taxes and the endless, hidden sorrows of men.

©1991 Peter Marin

Peter Marin, a freelance writer in Santa Barbara, California, is examining homelessness in America.