“As much money as they take out of here, this place should look like New York,” Ken Wiwa says, gesturing at the passing landscape as his car, chauffeured by his father’s driver, Sonny, speeds southeast from Port Harcourt towards Ogoniland along the area’s only major road. The buildings of the city quickly give way to fields of banana and palm trees. Two gas flares, one at a local petrochemical plant, the other burning above the area’s lone oil refinery, are visible through the foliage, like palm trees with undulating orange flames in place of green fronds. Dozens of oil trucks are parked at the roadside, awaiting the opportunity to fill up with shipments of gasoline bound for all over Nigeria when the refinery opens on Monday morning. The scenery is lush and green, but except for the road, the nearby industrial plants and the occasional shack, it’s devoid of construction. Hardly a New York skyline.

“Over there, near the gas flares, it never gets dark,” Ken says, pointing at the flames on the horizon. The acrid, heady smell of oil fumes is ubiquitous, engulfing the car and blanketing the vicinity, palpable in each inhaled breath.

Oil companies have been drilling in the Niger Delta since 1958, and Ken’s father, Ken Saro-Wiwa, is credited with coining an oft-quoted allegory for their relationship with the local communities: “It’s like taking a shirt from a man and giving him back a button.” The region has reportedly yielded 900 million barrels of crude and generated an estimated $100 billion in oil revenue since 1958, $30 billion in the last 12 years alone. But there’s little evidence of that windfall in the Delta.

Redressing the obvious discrepancy between the poverty that prevails in the Delta and the wealth that is siphoned from it was a cause that obsessed Ken Saro-Wiwa. He co-founded the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) in 1993 to campaign for his people’s right to fair treatment by the oil companies and Nigerian elites exploiting and polluting their land. He once revealed to his son Ken that “Everything…was for one purpose: to secure justice for our people. His books, the properties, the businesses–everything was subservient to his hopes and ambitions for our people.” Ken Saro-Wiwa was single-minded in his struggle. And it was a crusade that ultimately led to his execution by the murderous military regime of Sani Abacha.

Although Ken Wiwa was raised with a sense that he was expected to follow his father’s lead, in his teens he was “firmly apolitical” and he remains wary of political engagement. While many activists argue that the situation for local Delta communities has gotten worse since Ken Saro-Wiwa’s execution and Nigeria’s return to civilian rule in 1999, and while angry youths continue to capture and ransom foreign oil workers in the region’s intensifying oil wars, Ken hasn’t traveled to Nigeria from his home in Canada to take on Shell or lead an Ogoni protest march. He’s here on this Saturday morning to tend to other aspects of his father’s complicated legacy.

Ken has a vision, much as his father did. But while Ken Saro-Wiwa’s strategy involved political protest and direct action, Ken Wiwa wants to empower his family and people at his own pace, on his own terms and primarily through promoting economic independence. He’s expanding his father’s business empire into producing, marketing and distributing palm oil products, the Delta region’s one cash crop, and has plans to open an Internet café and business center. Before coming to Nigeria, he was in Brazil visiting an indigenous community along the Xingu river, where the locals seem to have struck a mutually beneficial arrangement with commercial ranchers who have agreed to contribute to the area’s development in exchange for access to grazing land. Ken hopes this Brazilian model can serve as an instructive solution for the conflicts that continue to pit local populations against multinational oil companies in the Delta.

Since he’ll only be in Nigeria for a week on this trip, Ken’s days are filled with business meetings and consultations with colleagues, family members and friends. And in addition, he’s hoping to conclude arrangements to finally have his father’s remains exhumed from the mass grave in which he was buried with eight other executed activists, and re-buried in Bane, the family village in Ogoniland, an hour southeast of Port Harcourt. It’s a process that has long been stymied by political and bureaucratic interference — while a funeral was held and a memorial to Ken Saro-Wiwa erected in Bane, the casket that was lowered into the ground in April of 2000 did not contain a corpse.

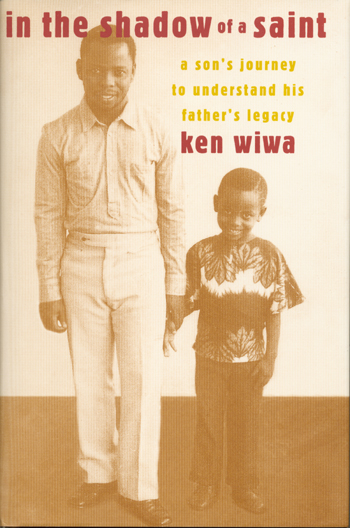

The journey from being a resentful teen at odds with his father over most matters to becoming the son who has gamely taken on a role as chief custodian of the Ken Saro-Wiwa legacy was long and tortuous. Achieving a level of comfort with being Ken Saro-Wiwa’s son has not been easy. In fact, Ken Wiwa was so obsessed by living in his father’s shadow that he devoted three years to writing a book about it. In the Shadow of a Saint (Knopf, 2000) represents Ken’s struggle to come to terms with his own troubled relationship with his father in the bitter aftermath of his execution.

“My father. Where does he end and where do I begin?” Ken wonders in the memoir. “I seem to have spent my whole life chasing his shadow, trying to answer the questions that so many fathers pose to their sons. Is my life predetermined by his? My future defined by my past? Is his story repeating itself through me, or am I the author of my own fate?”

Ken was twenty-six and living in London when his father was imprisoned in 1994, ostensibly as a suspect in the murder of four political opponents. Sent by his father to study in England since the age of ten, Ken Wiwa had remained abroad after graduating, pursuing a career as a journalist in spite of his father’s insistence that he return to Nigeria to assist in his family’s political and financial endeavors, persistent demands that merely complicated an already uneasy relationship between father and son. MOSOP had been actively struggling against the exploitation and pollution of Ogoniland and the Niger Delta by multinational oil companies since 1993, and the Abacha regime’s efforts to silence the movement’s charismatic spokesman galvanized international support for the Ogoni cause. Ken had always kept his father’s political activism at arm’s length, but when Ken Saro-Wiwa and fourteen other activists were detained and with his father’s life hanging in the balance, Ken found himself drawn into an international campaign to free his father.

When the campaign failed to prevent the execution of “the Ogoni 9” (Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight political colleagues were all sentenced to death in what most observers denounced as a sham trial), Ken Wiwa withdrew from the Ogoni movement and spent the next two years confronting the anger, resentment, guilt and regret conjured by his father’s “judicial murder.”

“My father’s supporters were willing me to carry on his struggle, to lead demonstrations against the huge multinational oil company and to provide a focus for opposition to the embattled military dictator,” he writes in his memoir. “It had the ingredients of a Shakespearean drama: Ken Saro-Wiwa was dead, and his son and namesake was primed to avenge his death. But like Hamlet, I hesitated, then left the stage altogether.”

By the end of In the Shadow of a Saint, Ken Wiwa isn’t much closer to answering “the questions that so many fathers pose to their sons,” but he has arrived at a degree of peace and accommodation with his father’s memory and legacy.

“Handling the by-products of your life has become something of a labour of love for me,” Ken addresses his father at the end of the book. “Managing your legacies is a full-time job, but I see myself as an unpaid volunteer, bonded by blood and inspired by both love and my determination to keep your memory alive.”

In practice, Ken Wiwa has effectively managed to strike a balance between living his own life and tending to the tasks that are his father’s legacy. He lives in Toronto with his English wife, Olivia, and two children, but every three months or so he visits Nigeria to see to various familial, financial and political chores. While he keeps his distance from the three factions of MOSOP into which the organization splintered after Ken Saro-Wiwa’s death, Ken seems to relish his role as curator of his father’s memory and business empire. And while Ken has retained his suspicion of politics, he is clearly influenced by his father’s ideas and does not rule out the possibility of involvement in Nigerian political affairs in the future.

“I think we need to develop the economic side of things first, then maybe get involved in political struggles,” he says. His father owned a retail business and numerous properties in Port Harcourt, the southern Nigerian city where the Saro-Wiwa homestead is located. Ken’s regular trips to Nigeria are occasions for monitoring the progress of the businesses he inherited as well as tending to more personal matters.

“I find myself having to navigate between worlds,” he says of his bi-continental lifestyle. “When I left Nigeria for England when I was 10, I spent all of my summer holidays here and I didn’t really miss it. But more recently I started having pangs, needing to eat some Nigerian food, or just missing being here. I guess it’s just a part of you.”

However reluctantly he came to the realization, Ken now understands he could never truly distance himself from Nigeria or his father. As he acknowledges in his book, “When I chose to reject my African identity I was only rebelling against my father,” and having made a sort of peace with his father, Ken has also come to sometimes uneasy terms with Nigeria, although he is clearly a product of two cultures.

In balancing his own life abroad with the needs and demands of his father’s inheritance and his family in Nigeria, Ken has managed to cultivate the Ken Saro-Wiwa legacy on his own terms, even if the local activists who often court his endorsement wish he would seek to provide more direct leadership in the ongoing Delta oil struggles. While Ken has not emulated his father’s political career in the ways Ken Saro-Wiwa might have hoped, he’s carefully extended the Saro-Wiwa business empire and cautiously come to play an important leadership role in his family. For him, for now, that’s enough.

He’s clearly taken to heart a conclusion he reached in his book. “The dead cannot be brought back,” he writes there. “And all that is left for us — the living — is to honour the dead by building a better future from the despair of the past, because those who forget the mistakes of the past are condemned to repeat them.”

The paved road ends abruptly as you enter Bane. Most of the houses consist of brown mud walls topped with corrugated zinc. Ken’s grandfather’s home is an exception, a two-story concrete building that towers over most others in the village. Chief Jim Wiwa’s home is flanked by several bungalows housing his six wives and their children, and Ken stops to greet his paternal grandmother before paying his respects to his grandfather. Everyone in the compound is excited to see him, and he exchanges greetings in Khana with his grandmother, cousins, uncles and aunts. In addition to offers of food, there are requests for assistance with various domestic problems, and coded complaints about the misbehavior of other members of the family. Ken listens politely but makes no promises, excusing himself after just a few minutes.

He finds his grandfather, a spry 97-year-old who still has most of his hair and most of his teeth, in an upstairs room of his home, with his sixth wife, a woman in her late thirties. After downing the shot of scotch his grandfather offers (taking care to first tip a splash onto the cement floor for the ancestors), Ken updates him in Khana on his business activities and informs his grandfather of his plans to finally have his father buried in Bane.

Though clearly pleased by the news, Ken’s grandfather is mistrustful of the government’s stated intention to allow the exhumation to take place.

“All Nigerian governments are corrupt,” he wheezes in English, betraying the bitterness of a man who lost his first-born son to a government-sponsored execution.

“I have to consult with him about everything,” Ken confides after concluding his audience with his grandfather. “Sometimes he doesn’t really have an opinion about what I want to do, but I still need to consult him first, because traditionally that’s the proper thing to do.”

After leaving his grandfather, greeting other relatives along the way, Ken strolls to the open field where the family buried a casket containing some of Ken Saro-Wiwa’s most beloved personal effects, including a pipe and some copies of his books. A small concrete building housing commemorative plaques honoring the slain activist marks the spot where the casket was buried and where Ken hopes to soon have his father’s remains interred. Although the area surrounding the structure is a bare grassy field right now, Ken’s vision is to create the “Ken Saro-Wiwa Memorial Gardens,” well-tended flowerbeds and walking paths that would attract pilgrims who admired his father from all over the world.

“At the funeral there were people standing all along here,” he says, gesturing at the meadow flanked by bush, where thousands had crowded to say goodbye to Ogoniland’s most famous son.

After a moment of solitary silent prayer and reflection in his father’s tomb, Ken makes his way back to his grandfather’s compound, stopping at a cousin’s house on the way to accept another offered drink. While he seems to appreciate the welcome, the burden of family obligation seems to take its toll, and Ken looks weary as he heads to his grandmother’s bungalow to eat the lunch that has been prepared for him.

Under pressure from Ken’s grandfather, Ken Saro-Wiwa had built a retirement home for himself in the family compound, which became the unofficial local MOSOP headquarters and meeting place, and is now a sort of shrine to both Ken Saro-Wiwa and the movement, with photos and poems of tribute lining the walls. But while the younger Ken has also been invited to build his own home in the family compound, he can’t imagine living in Bane.

“I try to spend as little time here as possible,” he says. “I could never live here. I’m too Westernized, and there’s no point in romanticizing life here and trying to be ‘authentic.’ I mean, even when I lived in Africa, I lived in the city, not in the village. I did spend a few days here once. It was a most uncomfortable experience.”

After taking a few polite bites of a lunch of garri (stiff cassava porridge) and fish and okra stew in his grandmother’s bungalow, Ken hastily completes yet another circuit of the compound to say his goodbyes, and seems relieved when he’s once again seated in the car as it creeps out of his grandfather’s compound along a rutted dirt track.

“Visiting the village always drains me,” he says tiredly.

As the car reaches the paved road and speeds up, heading back towards Port Harcourt, where he’ll spend three days in more business meetings before returning to Toronto by way of Lagos, he leans back in the seat and sighs.

“Freedom,” he says.

©2003 Philippe Wamba

Philippe Wamba was the editor of Africa.com. He was researching Africa’s new generation during his Alicia Patterson fellowship when he died Sept. 11, 2002. His car was hit by a truck in Kenya en route to interviews.