In For My Sons and Daughters, the South African poet Dennis Brutus conveyed a prophetic message to his children: “Memory of me will be a process of conscious and unconscious exorcism.” As noted by chroniclers and scholars of the human experience from Euripides to Freud, coming of age necessitates coming to terms with your parents’ legacy. In Africa, where a new generation stands poised to inherit control of a continent from elders who are slowly relinquishing their grip on power seized in the 1960s, the future will largely be shaped by the ways in which young Africans selectively embrace or reject their parents’ example.

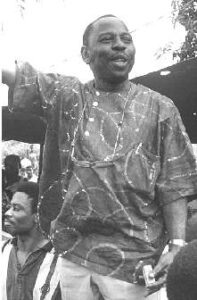

For Seun Kuti and Ken Wiwa, both sons of late and legendary fathers who loomed large in Nigerian history, this is a particularly onerous task. Seun’s father, Fela Anikulapo Kuti, was Nigeria’s most beloved popular musician and most acerbic social critic until his death of AIDS in 1997. Ken’s father, Ken Saro-Wiwa, was one of Nigeria’s most prolific writers and most outspoken political activists until his hanging by the repressive Sani Abacha regime in 1995.

Both sons grew up shouldering expectations that they would continue the work that their fathers had begun. But how can you emulate a lifestyle that may ultimately have been your father’s undoing? And how can you follow in your father’s footsteps when they lead straight to the gallows?

Although the function was supposed to start at 7:30 on this humid evening in Lagos, it’s already 8:30 and the guests are only just starting to fill the seats at the Eko Meridien Hotel Banquet Hall. Ushers show the formally attired invitees to circular tables adorned with balloons, while the event’s organizers, clad in caftans and flowing djelabas, huddle together near the stage, comparing notes. In one corner of the auditorium, filling four tables, members of the band that will provide the evening’s entertainment prepare for the festivities. Fifteen men wearing matching yellow suits chat and sip bottles of Guinness, while eight women in skimpy outfits with tasseled skirts peer into handheld mirrors applying red and white dots and stripes to their faces, arms and legs in ornate patterns.

One of the brightly suited men paces between the tables and the stage, gesturing at the instruments arranged on their stands, fretting to the sound engineer seated behind a huge mixing board, and throwing nervous glances towards the entrance, where two burly bouncers check the guests’ tickets before admitting them. His face brightens as he catches sight of a tall figure entering the auditorium and making his way through the growing crowd.

“Seun! Seun!” voices call out to the new arrival as he passes. He shakes hands with a few admirers as he walks by, but doesn’t linger as he heads to the corner, where he greets the assembled band members, removes his saxophone from its case, and starts playing along with the taped music pouring out of the speakers at either ends of the stage. It’s Fela’s “Suffering and Smiling,” and Seun deftly mimics his father’s sax runs, adding his own quirks and flourishes along the way, while some of the women at the table sing along as they continue to dab on their makeup. “Suffer, suffer, suffer, suffer, suffer, suffer for world — na your fault be that!”

Seun Kuti has been performing on stage since he was nine years old. He started his career as a backup singer in Egypt 80, the band fronted by Fela, the Afrobeat king who had presided over Lagos’s popular music scene since the early 1970s. Seun says he started teaching himself to play saxophone when he was eight, which is also when he started taking piano lessons. But on stage with his father he only ever sang, adding his child’s voice to the chorus of male and female backup singers that included his mother, the collective response to Fela’s persistent call.

Performing on stage with as many as twenty singers and musicians in regular sessions that sometimes went on all night was such an effective practical education that when Fela died in 1997, Seun, then just fifteen, was ready to take over. Since then, he has led Egypt 80 as lead vocalist and saxophonist, the focal point of a band that his father had forged into one of Africa’s most legendary ensembles.

While Seun is the front man, a star in his own right who is routinely recognized by fans on the streets of Lagos, in many ways Egypt 80 is still his father’s band. This gig at the Eko Meridien is a formal dinner and reception in honor of a returned Nigerian exile of Fela’s generation; the band plays two sets, between speeches by activists who probably recall Fela’s music as a cultural corollary to their own struggles against the Nigerian dictatorships of the 1970s and 80s. And a sense of nostalgia for both Fela and a bygone era holds sway on stage as well.

“Our hero Fela’s legacy was his music and his ideology. This is revolutionary music,” a band member shouts above Egypt 80’s bass and horn lines as the band launches into the first set. After an extended verbal tribute to Fela, Seun is finally introduced. “Seun Kuti!” the band member on the mike bellows. “The small boy with big man sense. He’s been struggling for African people’s liberation since he was in the womb.”

At nineteen, Seun is probably the youngest person on stage. Most of the band members, including Seun’s mother, who still sings backup, performed with Fela, and some look to now be in their fifties and sixties. And in addition to appearing in the same costumes they wore in the 80s, Egypt 80 still only play Fela songs. Tonight they do “B.B.C. (Big Blind Country),” “Army Arrangement,” “G.O.C. (Government of Crooks)” and “C.O.P. (Country of Pain),” each song lasting twenty minutes and peaking in the loud layered crescendos that were Fela’s signature, the dancers fanning out in front of the stage with their rears to the audience and shaking as if in the throes of rhythmic seizures, expressions of detached entrancement on their faces.

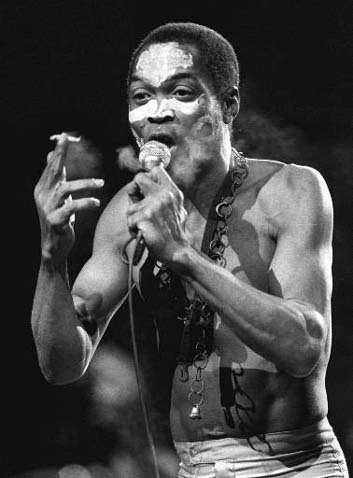

Fela’s Afrobeat was a pungent blend of funk and jazz with an African sensibility, reminiscent of James Brown but grittier, nastier and vaguely unsettling, like fermenting fruit. With Seun, Egypt 80 seem as explosive as they were under Fela, combining horns, keyboards, percussion, guitars and vocals in a sophisticated and overpowering blend that is at times discordant but always insistent. In the 70s the band performed almost nightly at The Shrine, a club Fela established, but these days they rehearse once a week and play three or four times a month at various venues around Lagos, sometimes alongside other artists.

In performance, Seun comes across as a perfect stand-in for his famous father. Tonight he’s dressed like Fela in a ginger 70s-style two-piece paisley print outfit, the pants tight around his hips and the wide-collared shirt open at his chest. At 6’1’’ Seun is taller than his father and has a darker complexion, but his face has the same high cheekbones, impish grin and dark, mischievous eyes. Fela was a lewd prankster, and Seun seems equally outgoing, bold and playful, with a short attention span, a loud and ready giggle and a restless child’s energy.

“Once you’ve met me, you can’t forget me,” he boasts. “I’m crazy. It’s just the way I am. My father was too.”

His singing voice is deep like Fela’s, and his saxophone hits the lines and hooks his father composed with the same muscular style, although he tries to bring his own flavor to the obligatory solos on saxophone and synthesizer. And like Fela, on stage Seun lives up to a reputation as a sex symbol, shimmying, winding his hips and often discarding his shirt, to the delight of female fans.

Seun was literally born to do this, and seems unconcerned by the constant comparisons to his father, unlike his half brother Femi Kuti, twenty years his senior and a more established and internationally known performer with whom Seun has a bitter rivalry. While Femi often seems to chafe under the burden of being his father’s son, Seun seems to embrace it. For Seun, taking up where his father left off is about building on Fela’s legacy, not trying to escape it.

“If I’m in my father’s shadow then it doesn’t trouble me to be,” he says. “If that’s all I can get, it’s a very good place to be. He was a very great man.” He pauses. “But of course every artist wants to define themselves.”

Seun says he and his father were close, and Fela’s death at the age of 58 hit the teenager hard. Fela had other children by other women, but took a special interest in Seun, who is one of only two sons to follow their father into a career in music. But while Fela set Seun on a path much like his own, having inherited the leadership of Fela’s band, Seun can be more selective about what else he chooses to take from the example of Fela’s life.

In 1978, Fela famously married 27 of his backup singers and dancers, including Seun’s mother, and divorced them all eight years later, saying he no longer believed in the institution of marriage. He was renowned for his profuse use of marijuana, his promiscuity, for performing in his underwear, and the 60s-free-love lifestyle he maintained at the compound-commune-concert hall he dubbed “the Kalakuta Republic.”

While Seun denies that his father died of AIDS (“He was just tired,” Seun has said by way of explaining his father’s death), he clearly avoids many aspects of the freewheeling existence that may have contributed to Fela’s premature demise. Although Seun likes to party and has a taste for Moët, he never smokes weed and appears monogamously devoted to his girlfriend Farida, a Lagos high school student.

In artistic terms he is also determined to chart his own course. Seun has just signed a deal with Virgin Records to record an album that will feature Fela songs as well as original tracks, and plans to innovate his own style, incorporating influences besides his father, including the hip hop (DMX, Wyclef Jean and Eminem are among his favorites) that comprises much of his own listening diet. And although he’s already a talented saxophonist, Seun hopes to refine his craft by pursuing formal musical training at the Trinity College of Music in London, where his father studied in the 1950s.

Seun also wants to update his father’s political message. He heartily endorses Fela’s politics (“He wasn’t afraid,” Seun says proudly) and relishes the fact that many of the songs he performs pillory by name Nigeria’s current president, Olusegun Obasanjo (who was also head of state in the mid-1970s when Fela recorded some of his most biting broadsides, including a track blaming Obasanjo for his mother’s death in an infamous army raid on Fela’s Kalakuta compound). But right now Seun seems unlikely to form a political party, as his father did in the late 70s, or to risk imprisonment with the kind of public antics that landed his father in jail on several occasions. And Seun hopes to offer his listeners a slightly different message from his father’s.

“I want to make Afrobeat for my generation. Instead of ‘get up and fight,’ it’s going to be ‘get up and think,’” he says. “My generation’s not thinking. It’s not really our fault. My father’s generation fucked everything up. And we haven’t been brought up to put it right. ‘Apparently, they weren’t parents,’” he adds, quoting Eminem.

The prospective Virgin album will be the first time Seun records his own compositions, although he claims to have already written more songs than he can count (“My head is still hot,” he says of his prodigious output). He’s never even performed his own songs, partly because he wants to perfect his own material in the studio before unveiling it for public consumption, unlike his father, who often debuted new songs on stage, recording them later.

“My father was stage to studio,” says Seun. “I’m going to be studio to stage.”

Seun once said “I have to play my father’s songs until I’m ready.” With an album of his own creations in the works, presumably he’s finally set to stake his own musical claim instead of trading on his father’s name.

In so doing, perhaps he can muster the kind of iconic voice and presence that made Fela one of his generation’s most politically influential cultural artists. It’s already clear that Seun’s name and music resonate with a new generation of Nigerians, many of whom are too young to remember his father’s heyday.

A week after the Eko Meridien gig, Seun and Egypt 80 perform at Onikan Stadium in Lagos, after speeches by the governor of Lagos State and other dignitaries commemorating the ninth anniversary of Nigeria’s abortive return to democracy in 1993, when military ruler Ibrahim Babangida annulled the results of much anticipated elections. The free concert attracts throngs of young people who ignore the political pronouncements and rush the stage when the band starts up, including droves of “area boys,” the tough street teens who control the roads of various Lagos neighborhoods, collecting “tolls” at makeshift roadblocks and serving as self-appointed community enforcers running various hustles to support themselves on the streets. The youths lose themselves in the beats and rolling basslines, singing along and cheering Seun on, swaying and stamping to the unrelenting Afrobeat grooves.

When Seun finishes his set, he leaves the stage and picks his way through the crowd, surrounded by area boys who call his name and pull at his grass green polyester suit. Seun is barely visible as the crowd moves with him, out of the stadium and towards a waiting Peugeot. The shouting and shoving area boys permit him and three companions to open the car doors and squeeze inside, then collapse around the vehicle, pressing themselves against the windows and doors, buffeting the car to and fro, all the while calling Seun’s name.

Once safely seated in the back seat, Seun reaches into his backpack and withdraws a wad of folded bills. As the money appears, the jostling intensifies, and Seun shouts commandingly at the faces peering into the car: “Wait, now!” Calm descends for a moment, then the car starts rocking again. Cracking the door, Seun passes the roll to a short, muscular youth with distinctive yellowish skin, the presumed leader of this crew of area boys, now charged with distributing the bounty. Slamming the door quickly, Seun shouts to the driver, and the car carefully pulls free of the mass of wrestling teenagers, their calls of “Seun! Seun!” slowly fading as the car leaves the stadium behind.

“I can’t forget them,” Seun says. “You have to represent for the streets.”

His friend Gabriel, seated in the front, leans back, eyes gleaming with exhilaration and amusement. “Area boys are not easy-o!” he says. “That yellow man must be strong. To be oga for area boys? It’s not easy.”

No, it can’t be easy to be a leader to the teeming, aggressive and often undisciplined legions of Nigeria’s youth. But maybe Seun Kuti is one man for the job.

©2003 Philippe Wamba

Philippe Wamba was the editor of Africa.com. He was researching Africa’s new generation during his Alicia Patterson fellowship when he died Sept. 11, 2002. His car was hit by a truck in Kenya en route to interviews.