Text and photos by Randall Hyman

TROMSØ, NORWAY – “When I got married two years ago, we invited 1400 people,” Berit Oskal-Somby told me as we stood in an icy coastal pasture in northern Norway surrounded by 1500 reindeer, “but only 1000 came.” When I asked, astonished, how she had provided dinner for so many guests, she swept an arm toward the herd before us and said with an amused smile, “You are looking at it.”

In many ways, reindeer are the symbol of Oskal-Somby’s people, known as the Sami within Norway and as Lapps across the border in Sweden and Finland. Less than 10% of the 50,000 Sami living in northern Norway still herd reindeer, and that number continues to dwindle as climate change, predators and habitat loss make this traditional livelihood steadily more difficult.

Oskal-Somby works at the Sami parliament, but in late January 2015 she and her extended family gathered for an unusual event. All hands were on deck to corral reindeer stranded by unseasonal snows in November and truck them off to the snowy highlands where the main herd had already migrated. The sun had recently returned to this Arctic region after two months below the horizon, but the distant city lights of Tromsø were already blinking on in the early afternoon. As we spoke outside the corral, the fleeting orange glow of sunset shone through the sleet and reflected in her blue-grey eyes.

“I invited my second and third cousins, because they, to me, are close,” she mused, as if to explain why she had so many guests at her wedding. “But in the Norwegian culture, they wouldn’t be.”

In comparing her own culture to the “Norwegians,” she alluded to the shadowy schism that exists between the indigenous Sami and the descendants of the Norsemen, who began colonizing this region four centuries ago. As the original inhabitants of northern Scandinavia, the Sami knew no borders and roamed freely across Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia’s Kola Peninsula, hunting wild reindeer for their own needs. Land ownership was a foreign concept. With increased colonization, taxation and firearms in the 1600s, the Sami began overhunting to cover debts before turning to raising domesticated reindeer as a better solution. The organized tradition of herding reindeer from snowy mountain plateaus in winter to lush coastal pastures in summer was born.

Communal herding ensured a deep and extensive family structure, but missionaries and colonists considered the Sami savages and demonized their shamanistic religion. Centuries of Christianization and forced assimilation diluted their Finno-Ugric traits, rendering the Sami every bit as Norse-looking as those they call “Norwegians.” Although physical differences may be invisible, cultural differences and prejudice persist.

“A couple of years ago there was talk about whether Tromsø kommune [municipality] should have to write official letters in both Sami and Norwegian,” Oskal-Somby recalled. “Some people yelled at us in the street and threw things at those in traditional clothing.”

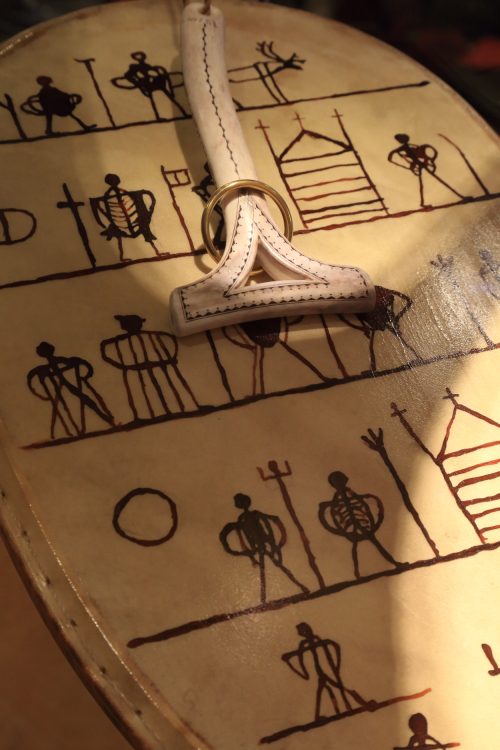

Despite a government policy that banned speaking Sami in schools as recently as the 1970s, the Sami have emerged in the 21st century with limited self-rule and a modern parliament building. They are fiercely proud of their Finno-Ugric language, unique music (particularly the yoik, a type of chanting that channels the spirit of all things, animate and inanimate) and their reindeer culture. While the language and music are alive and well, the reindeer economy faces a cloudy future.

The unusual presence of the Oskal herd along the ocean shore in January illustrated just how much climate change and predators are affecting their livelihood. When heavy snows hit earlier than usual in November, many reindeer were stranded in the lowlands. The Oskals decided to fence in the animals along the coast and feed them rather than move them into the mountains since highland predators have decimated their calf population in recent winters.

“It’s good for us since predators aren’t as big of a problem here on the coast,” explained Johan Isak Oskal as he prepared to wade through a frantic mass of clacking antlers in the corral to help sort and drag animals to separate pens. “Some years in the mountains we’ve had only five percent of the calves survive the winter because of the predators.”

By concentrating their reindeer in a fenced pasture, the Oskals were able to reduce losses from eagles, wolverines and lynx, but feeding so many animals is expensive. The one-ton sacks of specially-formulated reindeer food they were putting out cost about $700 each day, but recent icing had forced them to double that amount.

Reindeer normally fend for themselves, eating lichen in the highlands by pawing through the dry, powdery snow that is prevalent at higher elevations due to consistently bitter temperatures. By contrast, coastal snows are often layered in ice caused by alternating periods of rain and freeze, which makes the ground impenetrable. While coastal icing is nothing new, it has begun creeping into the highlands as well. Finnmark’s weather records show an upward trend in the annual mean temperature since 1980 of about 0.5°C (almost 1°F) per decade in the high mountain region.

“You remember well when you work with reindeer,” one of the family elders, Isak Tore Oskal, told me, “so you notice the good winters for grazing. We had a sudden change from 1980, and ever since we’ve had winters where we’ve had bad grazing, with more icing. And we’ve had to give more feed. Our winters have become milder.”

Back in Tromsø, I discovered that the picture was even more complicated due to government policies that fail to understand traditional Sami perspectives. Anthropologist Marius Warg Næss, of the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research, has studied the effects of government policies on indigenous herders worldwide, from Tibet to Norway.

“The Norwegian government is not happy with reindeer husbandry, especially in Finnmark– there are just too many reindeer.” Næss explained. “The problem is with overgrazing. In the time from summer to winter we have had reindeer starve to death, so the government policy is to reduce the number of reindeer by subsidizing prices to encourage more slaughter.”

The introduction of strict government control over reindeer husbandry in the late 1970s has led to controversy. Subsidies for extra slaughter benefit those in need of extra cash, rather than the wealthier, larger herding families. Larger herds stay large while smaller herds dwindle, and for the Sami, large herds are a hedge against climate change and predators. Finnmark, Norway’s largest and northernmost county, is twice the size of Vermont, but biologists believe that the total herd of 180,000 reindeer grazing its open range exceeds the land’s carrying capacity.

“It’s just a mess,” Næss continued. “Sami herdsmen have a totally different logic than the government. When prices are high, they can slaughter less animals for the same income. No amount of subsidies will increase slaughter volume if herd accumulation is the Sami’s main goal.”

For the Sami, herds are a savings account; the larger the herd, the bigger the nest egg. That works if pastures are unlimited, but another unintended impact of state interference has been the incremental loss of land from hydroelectric projects, military installations, mines, power lines, pipelines and roads. According to the Stockholm-based International Arctic Science Committee, Finnmark County has lost some 35% of previously undisturbed reindeer habitat in the past 60 years. Næss says that one long-range climate prediction is that more erratic winters will occur more frequently. The Sami strategy for dealing with icing caused by temperatures that leap above and below freezing is to move reindeer from unusable pastures to ice-free ones, but the steady encroachment of private and government property has limited that flexibility.

Months after visiting the Oskals, I drove through a vast Finnmark wilderness and important reindeer habitat called Sennalandet to see how fragmented the mountain pastures have become. It was the first of May, and a late snow had covered the highlands with a fresh white blanket. I followed a narrow ribbon of black road through the mountains as blasts of wind obscured distant slopes with blowing snow. Snowmobilers and skiers eager to stretch winter a bit longer unloaded lines of vehicles in crowded parking strips strung along the highway. Cottages and second homes dotted the high plateau, crisscrossed by power lines and fences. It was a reindeer herder’s nightmare.

“Climate change, predators, big power lines– we have lots of problems,” Per John Anti, a reindeer herder in northern Finnmark County had told me earlier that day when I visited him at his tiny hut in the coastal mountains overlooking the Barents Sea. He and his colleagues had arrived from the highlands just a few weeks earlier with a herd of 6000 reindeer.

“We had snow last night, but if we drive higher up now and see the older snow, it’s very hard– it’s ice. The reindeer can’t paw through that to get food,” he said, as he carved himself thin slices of reindeer meat with a traditional Sami knife. “We are like the Indians or Eskimos living off nature. If we continue losing land, we will not be able to keep reindeer. In 50 years we will have to do something else.”

As I drove along the highway, the vast, snowy highlands seemed endless, but reindeer herders see it differently. From their perspective, fences, roads, power lines and land grabs have decimated traditional pastures and migratory routes, leaving reindeer ever more vulnerable to climate change and predators.

Mulling over Anti’s words, I imagined the Sami without reindeer and without their connection to nature, without a reason to be outside braving the endless darkness and bitter cold of an Arctic winter or enjoying the midnight sun and lush bounty of summer. Another herder I had visited the day before in Karasjok, home of the Sami parliament, echoed some of Oskal-Somby’s sentiments from months earlier.

“Most of the time,” Anne Louise Gaup told me, “when I am yoiking, it’s actually in the springtime, when we are moving with the reindeer herd to the summer area. Then I yoik because I can see the reindeer have had a good winter and the female reindeer are pregnant. I am so happy about that,” she laughed. “Then I yoik because I am proud.”

SIDEBAR: THE LANGUAGE OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Languages offer insight into cultural priorities, and the Sami language of northern Norway boasts one particularly remarkable feature: it has over 300 words to describe snow, many of which relate to the snow’s good or bad qualities regarding reindeer. Describing everything from icy to powdery snow, these ancient words reveal that Finnmark’s climate has always fluctuated, but the modern combination of rapid long-term warming, habitat loss and increased predation may be more than the Sami and their reindeer can handle. The following list shows how keenly the Sami observe nature’s nuances and how their language has become a barometer of climate change.

Cearga: Hard-packed drift snow “which one can’t sink one’s staff into” and is impossible for reindeer to dig through.

Ciegar: Snow that has been dug up and trampled by reindeer, then frozen hard.

Fieski: Snow in an area where only a few reindeer have been, as evidenced by few tracks.

Oppas: Thickly-packed snow through which reindeer can dig if the snow is luotkku (loose) or seanas (see below).

Sarti: A layer of frozen snow on the ground at the bottom of the snow pack that represents poor grazing conditions for reindeer.

Seanas: Dry, coarse-grained snow at the bottom of the snow pack that is easy for reindeer to dig through and occurs in late winter and spring.

Skárta: A thin layer of frozen, hard snow on the ground that forms after rain and creates poor grazing conditions.

Text and photos by Randall Hyman

© 2015 Randall Hyman