“It is only necessary to build a manufacturing village of shanties, in a healthy location in any part of the State, to have crowds of these poor people around you, seeking employment at half the compensation given to operatives at the North…who, if too lazy to work themselves, might be induced to place their children in a situation in which they would be educated and reared in industrious habits.”

— William Gregg, Essays on Domestic Industry (1845)

“The village had been laid out in broad streets and large squares; and upon these neat, uniform cottages were built which, with a large lot of land to each, were offered at a very low rent to those who would bring in their families and place them in the mill.

“The plan worked well. The houses were soon filled with respectable tenants who paid a fair interest on this part of the capital; and, while the sons and daughters worked in the mill, the father would engage in cultivating his land, hauling wood, etc, and the mother would attend to the housekeeping department…’”

— James Taylor, Treasurer of the Graniteville manufacturing Co., in De Bow’s Review (Jan., 1850)

Graniteville’s Leisure Years club was organized in 1971 and today has almost 200 members, all retired employees of the Graniteville Company. Their clubhouse is a two story gothic cottage on Front Street whose scalloped eves, steep pitched roof and vertical ribbing mark it as one of William Gregg’s personal creations. The building was designed and built in the late 1840’s as part of Graniteville’s original mill village, and for almost seventy years it housed the Graniteville Academy, Gregg’s personal “nursery for the best class of factory operatives.”

“Aside from a charitable point of view, he had written to the Company’s Board of Directors in his last published report shortly before his death, “it (the Academy) is most assuredly a source of profit, and the money spent upon it will produce a rich harvest of results.” Immediately following Gregg’s death, however, the Company’s widely publicized commitment to the education of its mill children gave way to a so-called “petition of citizens” (whose citizens included only supervisory personnel of the Company by name), and all Company regulations regarding compulsory schooling of all children under twelve were abolished.

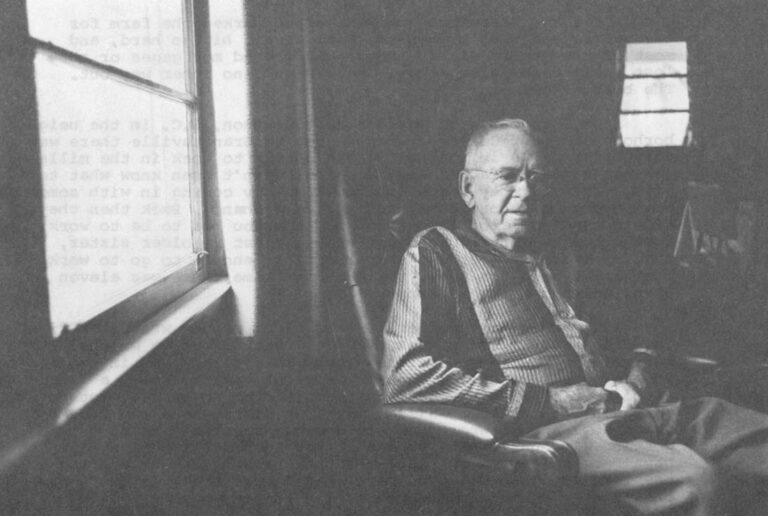

The Academy survived until after the First World War when the Company, under the urging of the State Board of Education, decided to build a full scale grade and high school only a few blocks up Front Street from its predecessor. As the years passed and the old building began finally to deteriorate, the Company at first simply considered tearing it down, then decided perhaps it should be restored into an archive museum for the Company’s historical collection of records and documents, but in the end the high risk of fire in a building of its age convinced them to donate the archive to the University of South Carolina and to give the old Academy instead to the newly formed Leisure Years Club for use as a clubhouse. Ansel Thompson is 67 years old and is one of the Club’s charter members. Early this Spring he and Harold Long, his next door neighbor and long time fishing companion, boated a 30 lb. turtle up at the Slade Lumber Company Pond, easily the biggest turtle either of them could remember having caught in a good long time. To celebrate, Ansel decided to make a stew for that week’s gathering of nook and setback players at the Club. After cleaning and dressing the turtle to about 10 lbs. of meat he took an old five gallon cast iron wash pot, rigged a small gas burner underneath it and added 12 lbs. of beef, a whole chicken, 5 lbs., of Irish potatoes, 3 lbs. of onions and a large can of tomato paste. By early afternoon the mixture had begun to bubble softly from the kitchen, and Ansel took a moment to lean back in his easy chair and reminisce.

“I can still remember way back to when all of us children were picking cotton. One day we all started back to the house and my oldest brother told me to go with granddaddy because he was way up in age. We started up the path until we got about a few hundred yards from the house, and he just kind of slumped. I grabbed him, and I let him down on the ground, and when my oldest brother got to him he was dead. He’s buried up in Graniteville cemetery.”

“My granddaddy has the same name as I have, and therefore my tombstone marker is up there in Graniteville cemetery right now. John A. Thompson. I remember when I was little he used to get mail addressed to John A. Thompson, and I used to think, well, part of that ought to be mine. But I learned better later on.”

“I could always do my figuring, but I never could write or read… other people’s writing. I didn’t have the education. I had the skill of workmanship with my hands, but I never felt like I would be an educated man. You see some people are gifted to different things. If I was gifted to any one thing, it was to work with my hands, and the knowledge I have gained from other people by watching them do something.”

“You see, when I was a child and growing up, until I was seven I had epileptic fits. So I was one of the children that didn’t get no education. And it was rough on the farm. We had plenty to eat, but we didn’t have a whole lot else. We were like a lot of people then though. You had something to eat, but you had no luxuries. There wasn’t any luxuries. Other people didn’t have them either.”

“By 1917 there were 12 of us, and one day my daddy got the flu and it left him an invalid. He couldn’t farm. Therefore the rest of us worked the farm for two years, and that’s when the boll weevil hit so hard, and most of the people either had to get second mortgages or they lost their farms altogether. There wasn’t no other way out. The bottom fell out.”

“We lost ours. It was out near Johnson, S.C. in the neighborhood of Mount Calvary. When we got to Graniteville there was only three of us in the family old enough to work in the mills at that time. My father and my mother didn’t even know what textile work was. They were farmers. Somebody coming in with some age on them in those days didn’t have a chance. Back then they didn’t have no labor laws about how old you had to be to work. That’s how we survived and got along. First my older sister, then my two brothers, and then I got old enough to go to work. Then one by one the rest, until at one time there was eleven of us working for the Company.”

“I can still remember just as clear as day what that first pay check was. $2.52 a week. We drew that for three months. They had quite a few young children then. They’d take you in and train you for the more skilled jobs. You might have to sweep a little or pick up bobbins or clean up the floor or something, but you got a chance to learn skilled work. It didn’t take one too many years to learn to where you could get a regular skilled job doffing. I count myself as one of the luckiest men of my age, to have been raised on the farm and then brought in and started a new life and made good and have what I have today. I count myself one of the luckiest men Graniteville Company has turned out.”

“The Company didn’t have any real benefits plan until about ‘35 or ‘37. When this Pension Trust Fund was set up, it was actually set up for the benefit of the overseers not the workers. You had to make maybe $2500 or $3000 a year to qualify for it, and the highest pay a skilled worker made at that time was about $30 a week. But as the rest of the people advanced in wages, they became eligible to participate in it.”

“In the fall of 1941 I went on seven days a week and worked seven days a week until I retired in 1970. I never did get a vacation in 28 years. Never a whole week at a time. During vacation time when everybody else was taking theirs, they needed me on my job. And I did stick with them, and I can say it paid off. But it was awful hard. If I’d have had my way, there was several times that I would have been on a vacation with my family because my wife was off work. But I had to work on.”

“I can see it now, and if I had it to go over I would never have worked that first Sunday. If I had my life to live over, that’s my only regret. Once you worked the first Sunday, that was it. You was hitched then. The first Sunday that I worked I didn’t want to, but they needed me in this particular job, and I committed myself to do it until they finally got to where they demanded it. Yes, it was 1941, October of 1941, when I worked my first Sunday. Put in 14 hours that day. Wasn’t but a week or two after that but what they wanted me to work every Sunday.”

“I guess I would have liked to go back to the farm if I could. I talked to my wife a few times about it, but she didn’t want to. She’s never lived nowhere else but here in Graniteville. She didn’t want to, I had a chance to take a fellow’s farm and operate it as mine as long as he lived, and then at the end of his time it would become mine through inheritance, but she didn’t want to. She didn’t want to live in the country. Therefore I turned it down and stayed with the Company.”

“She gets depressed at times, I don’t know. That’s one thing that doesn’t happen to me. Oh I have things that bother me, things I can’t control. But I feel this way, if you can do anything about whatever it is, then try to do something even if you fail. And then if you fail, forget it and start all over again. But if you can’t do anything about it, why worry about it. As far as that goes, there’s not too many people that can retire and live like we’re living and have what we have and enjoy it like we do. It’s not that I’ve got that much money, but I’ve got lots to be thankful for. And that’s what life’s all about. If you’ve learned that you didn’t have a whole lot but you had plenty, then you got all you need.”

Ansel Thompson’s home is a sturdy one story brick house that he and his wife designed themselves. It lies on about an acre of land sloping downhill from Eargle street as it leaves the strict regimentation of Graniteville’s company-built row houses. At one time this section of Graniteville was the only private property in town not owned by the Company. In 1954, when Ansel and his wife found out that the old Quimby estate was being subdivided following the death of James L. Quimby the town merchant, they decided to take a chance and make a down payment on one of the lots.

Photographs courtesy of Mr. Fraser Sofge, assistant treasurer and photographer for the Company 1935-1956.

Today it is twenty-one years later, and that acre of land and its house have been completely paid off and are theirs free and clear. It is four o’clock in the afternoon, and a cool spring rain has just begun to fall on Ansel’s garden as he walks out through the freshly seeded rows of sweet corn, collard greens, potatoes, sweet peas, okra and strawberries beside his eight pecan trees, four oak trees, three pear trees, plum, dogwood and scuppernong. It’s Sunday, and Ansel is having his picture taken.

©1975 Richard Pearce

Richard Pearce, a freelance film-maker/journalist, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Pearce and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.