"The real ruling class could not be put in question, so they were seen as temporarily absent, or as the good old people succeeded by the bad new people — themselves succeeding themselves. We have heard this sad song for many centuries now, a seductive song, turning protest into retrospect, until we die of time."

— Raymond Williams, The Country and the City, 1970.

"Happily for me, my two eldest sons have turned their attentions in this direction, and I feel that the foundations I have laid in that line of business will now grow until a mighty structure is reared, and then we may look for Manufacturing Princes among us such as they have in England…James has given a new impetus and I now feel that in my failing years, the business which I have reared will go on with renewed vigor."

— William Gregg in a letter to James H, Hammond on Jan. 7, 1859.

James J, Gregg, the son of William Gregg the founder of Graniteville, was eleven years old when he first took the eight hour journey with his mother from their home in Charleston up into the piedmont hills to the site of his father’s new factory. It was March of 1847 and the South Carolina Railroad from Charleston to Hamburg had recently opened a new depot, even though it would be almost another two years before the factory could begin production. And, as the railroad only came to within a mile of the site, the tiny new station with its freshly painted sign silhouetted against the woods seemed almost to have snagged itself like some brightly colored leaf caught momentarily in the downstream rush of a creek.

James and his mother had made the journey to be at band for the Graniteville Manufacturing Company’s first stockholder’s meeting at the new factory; and, as the train disappeared into the distance, they found themselves deposited on a bare platform not much larger than a good-sized Charleston dining room table, surrounded by what apparently was an impenetrable forest of pine. The boy and his mother must have looked on helplessly as a swarm of spring mosquitoes descended out of the enveloping silence upon the some half dozen furiously overdressed, unintroduced Graniteville stockholders standing with them on the platform, each of whom at least for the time being was determined to ignore the gathering probability that this whole thing had been perpetrated upon the lot of them as some sort of elaborate outrageous practical joke.

Even the sudden arrival of James’ father in the large wagon with its canvas awning to shade them on the drive to the factory site served only, it seemed, to confirm the stockholders in their construction of the event and further to convince them of his father’s now certain culpability in the matter. Years later his mother was to remark that she was sure that secretly those men never forgave father for being late to meet their train that day in March of 1847.

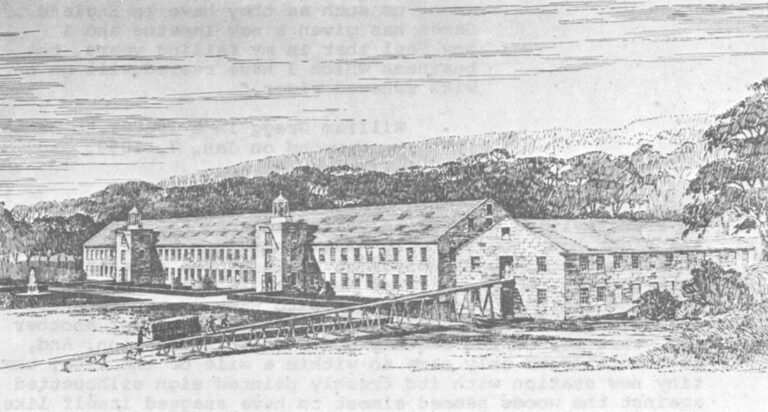

"When Graniteville burst upon our view from the summit of the hill, its main building of white granite, 350 feet long with two massive towers ornamented at the top, looking like some magnificent palace just rising out of the green vale below, with an extensive lawn in front and clean trimmed gravel walks around and fountains spouting their crystal waters in the air in fantastic shapes; the neat boarding houses and cottages for single families and the handsome little church, all constructed and ornamented in the ancient Gothic style, and each house having its own garden for vegetables and flowers; and the evergreen woods sloping from their garden doors gradually to the summit of the hill where we stood — the whole scene is as though the wand of the enchantress had called it into existence to challenge our admiration."

— Thomas Maxwell writing for the Tuscaloosa Monitor in 1848.

Father

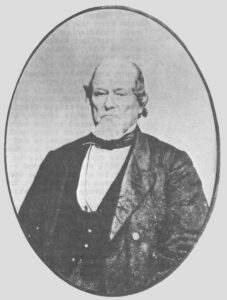

"In 1836 my career as a manufacturer commenced."

— (William Gregg to the Manufacturer's Association of the Confederate States, 1864).

"Where such men control, you never hear of strikes and mobs among their employees. They not only lift themselves up in the scale of being, but give life to all around and about them. All honor to such noble specimens of the highest type of manhood in our new South…. May God multiply such men by the thousands all over this sunny land of ours."

— (Editorial in the Raleigh Christian Advocate quoted in Liston Pope, Millhands and Preachers).

Born November 25, 1836: James Jones Gregg in Columbia, S.C., to William and Marina Gregg of that city.

It had been over a decade earlier during the summer of 1836 that William Gregg, then a wealthy merchant in Columbia, had for reasons of ill health decided to close his jewelry business in the city and retire for a time with his family to the plantation home of his father-in-law in Edgefield, S.C. Nearby, in the sandy pinewood forests of Upper Horse Creek Valley, stood a small cotton and wool factory called the Vaucluse Manufacturing Company whose 1520 spindles, 25 looms, and combined work force of 30 slaves and 20 whites had during the last several years fallen into considerable neglect.

The factory had been built about five years earlier on the burnt-out foundations of a previous mill that probably dated back to the years of the Napoleonic wars, when a series of import restrictions and embargoes on British cloth produced an extraordinary number of what only could be described as home-made textile mills to meet the country’s sudden demand for locally manufactured cloth. Most of these, including Vaucluse’s predecessor it would seem, collapsed when inevitably trade reopened and the accumulated store of British goods flooded the country selling at or even below cost in order to recover for the Lancashire textile barons of the day what had become an extremely lucrative export market,

And so William Gregg that summer began making regular visits to Vaucluse, until by the fall he had bought a considerable interest in the company and had decided to return the following year to try his hand at operating it himself. Eight months later, not only had Gregg wiped out Vaucluse’s $6,000 debt while earning a profit of some $11,000, but he had succeeded in proving to himself conclusively that the manufacture of cotton was not only a feasible and in fact profitable way of making a living in the South but was also absolutely necessary to her future preservation and well being. William Gregg’s career as a manufacturer had truly begun, and he was well on his way to becoming, in the words of his biographer Broadus Mitchell, “the South’s first great bourgeois, the forerunner of a new era.”

Unfortunately, however, some sort of disagreement seems to have arisen between Gregg and George McDuffie, Vaucluse’s president and the owner of many of the company’s slave operatives, and on February 25, 1837, McDuffie sent a letter of resignation to the company with this proviso:

“I have but one instruction to give, and that relates to the price to be allowed for my hands…. I have agreed to let my hands remain, if they will allow $700 per annum for those five, and $300 for the carpenter Jesse. I can get a dollar a day for the carpenter Jesse. If these prices are not allowed I will take them away….”

Existing records give no clue as to the circumstances surrounding McDuffie’s resignation, but one thing is clear: shortly thereafter Gregg decided to abandon his project of taking over Vaucluse and instead moved with his family to Charleston, where he returned to the jewelry business. Yet it was only just a matter of time before the graceful and leisurely pace of antebellum Charleston began to infuriate Gregg, and his attention began once again to stray from the aristocratic confines of the jewelry trade.

“What city besides Charleston,” he was to write in an outraged anonymous article in the Charleston Courier,” forbids the use of steam by its mechanics, “lest the smoke of an engine should disturb the delicate nerves of an agriculturist; or the noise of the mechanic’s hammer should break in upon the slumber of a real estate holder or importing merchant while he is indulging in fanciful dreams or building on paper the Queen City of the South — the paragon of the age?”

By the spring of 1844, James Gregg’s father had decided to launch a single-handed campaign to convince his planter friends of Charleston that the South must diversify its capital and invest it in the manufacture as well as the cultivation of cotton if she ever hoped to free herself from this steadily increasing dependence on her industrious neighbors to the north. The South must create a “domestic industry” of her own instead of just reclining on her plantation verandas while her precious wealth daily filled the coffers of Boston and New York shopkeepers and industrialists.

That summer Gregg made a tour of New England textile mills and marveled at the high level of organization of the Boston mill owners who “club together…so that they are constantly appraised of what others are doing…. Each factory (has been) erected for a particular purpose and confined exclusively to it…. Their hands, having but one operation to perform, become so completely drilled in it that they are run at a speed incredible to one who has never witnessed it.”

Finally in September the Charleston Courier published the first of eleven articles entitled “Encouragement of Domestic Industry the True Policy of South Carolina” signed “South Carolina.” The articles stirred such an immediate interest and were so widely quoted by other newspapers throughout the South that by early 1845 the Courier announced the publication of these “Essays on Domestic Industry” in pamphlet form under the authorship of one “William Gregg Esq, of this city, a gentleman by his connection with the Vaucluse Factory.. and his recent examination of Northern Factories, qualified to speak on the subject with all the weight due to practical experience and an enlightened judgment.”

“I cannot see how we are to look with reasonable hope for relief.” Gregg wrote in the first essay, “without a total change of our habits. My recent visit to the Northern States has fully satisfied me that the true secret of our difficulties lies in the want of energy on the part of our capitalists and ignorance and laziness on the part of those who ought to labour.”

Apparently with his opening shot Gregg decided to waste few words and instead to strike home directly into the heart of the Southern planter’s aristocratic self image. For the entire political, economic and cultural edifice that was antebellum Charleston was predicated upon the sacred assumption that the highest form of human activity was the white man’s conspicuously public leisure and the lowest was the black man’s conspicuously public labor. Nor was it any longer simply a defense of white supremacy. For by now the two modes of life had become interwoven into such a finely textured pattern of symbiosis that each had become a sort of inverted mirror image of the other: with the white man’s determined and desperately public leisure becoming little more than a pale reflection of the black man’s graceful and unhurried private labor, and the so-called “natural” hedonism of the slave simply an inverted image of the ferociously repressed Puritanism of the master. But in Charleston in 1844 to confuse these two was unthinkable. Worse, it was heresy. And William Gregg knew it.

“Experience has proved,” Gregg went on to write, “that any child, white or black of ordinary capacity, may be taught in a few weeks to be expert in any part of a cotton factory….” But Negroes should be preferred to whites for two main reasons:

“First — you are not under the necessity of educating them, and have, therefore, their uninterrupted services from the age of eight years. The second is that when you have your mill filled with expert hands, you are not subjected to the change which is constantly taking place with whites…. We possess the cheapest, steadiest and most easily controlled labor to be found in the United States…. All concur that there is no difference as to the capability; the only question is whether hired labor is not cheaper than slave labor.”

What Gregg is saying here is that the decision as to whether one uses slave or free labor is a relatively arbitrary one, just a matter of a few dollars more or less either way, certainly posing in itself no threat to the basic structure of the plantation economy. Of course, he is quick to point out, slavery “should be preferred” as the ideal form of all labor, “not subject to the change which is constantly taking place with whites.” But if for some reason whites could be found who were as cheap or even cheaper than slaves, and as steady and as easily controlled, then why could we not use them too? For in that case slavery would be, if not the actual agent, certainly the “foremost assistant to industrial development in the States of the South Atlantic Seaboard;

it is the means of giving to capital a positive control over labor, even in manufacturing states, labor and capital are assuming an antagonistic position. Here it cannot be the case; capital will be able to control labor, even in manufactures with whites, for blacks can always be resorted to in case of need.”

Where once the institution of slavery was simply the means of giving one race “positive control” over another, it has now become, in Gregg’s words, “the means of giving to capital a positive control over labor.” The ancient Aristocratic Problem — of getting someone else to do your work for you — has here undergone a subtle sea-change of ideological assumptions. The traditional quasi-feudal divisions of men along fixed racial or caste lines have here given way to a more dynamic, ‘economic’ division of society into its basic productive components i.e., economic classes. Yet to a society where the right to the ownership of another man’s labor (if that man was black-skinned) was as sacred as the very right of private property itself, this shift from ownership of slave labor as a race to “positive control” over free labor as a class must have sounded dangerously subversive to Gregg’s audience. But that couldn’t have been farther from the truth.

For example, here is James Taylor, Gregg’s friend and associate in the founding of Graniteville, writing a few years later in De Bow’s Review:

“…so long as these poor but industrious (white) people could see no mode of living except by a degrading operation of work with the negro upon the plantation, they were content to endure life in its most discouraging forms, satisfied that they were above the slave, though faring often worse than he…. (But now) the great mass of our poor white population begin to understand that they have rights and that they too are entitled to some of the sympathy which falls upon the suffering…. It is this great upbearing of our masses that we are to fear, so far as our institutions are concerned…. Crowd from these employments the fast increasing white population of the South, and fill our factories and workshops with our slaves, and we shall have in our midst those whose very existence is in hostile array to our institutions.”

For William Gregg and his contemporary industrial pioneers in the antebellum South, the question was not whether owned (i.e., slave) labor could be freed, but on the contrary it was whether free labor could be owned or “controlled” through new manufacturing communities which like their plantation counterparts would create a “rich harvest” for their philanthropic benefactors. “Shall we pass unnoticed the thousands of poor, ignorant, degraded white people among us, who in this land of plenty live in comparative nakedness and starvation?” wrote Gregg, “It is only necessary to build a manufacturing village of shanties in a healthy location in any part of the State to have crowds of these poor people around you, seeking employment at half the compensation given to operatives at the North.”

“Allow that two-thirds of this fifty thousand (poor whites)…be required to raise provision,* make clothing, cook, wash, etc, for the balance, and we shall have left 16,666 persons…adding to the value of each pound of cotton (leaving a surplus of) $8,586,323.20.”

While McDuffie’s offer to rent his Vaucluse “hands” at $700 and $300 per year was perfectly reasonable under the circumstances, so was William Gregg’s decision to turn him down. For, as one early visitor to Graniteville from the North by the name of Solon Robinson was somewhat ungraciously to point out, whites were “cheaper than blacks…free to starve if unable to work. ” “Free” labor properly controlled could be, according to Gregg, the salvation of the very plantation system itself, without in the slightest disturbing its operation. For, Gregg was to write as if to seal his argument against any possibility of dispute,

“…it certainly would not make such draughts upon the agricultural population as to be felt, especially as women and children principally would be required.”

And so it happened that James J. Gregg was eleven years old when he first made the long journey with his mother from their home in Charleston up into the piedmont hills where his father’s new factory was being built.

“At a court of General Sessions begun and holden in and for the County of Aiken in the County and State aforesaid on Monday the first day of may in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and seventy six, the juror of and for the County aforesaid upon their oath present.”

“That Robert McEvoy not having the fear of God before his eyes, but being moved and seduced by the instigation of the Devil on the Twentieth day of April in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and seventy six with force and arms at Graniteville in the County and State aforesaid in and upon one James J. Gregg in the peace of God and of this State then and there being, did make an assault, and that he the said Robert McEvoy a certain pistol of the value of five dollars, then and there loaded and charged with gunpowder, and diverse leaden balls (which pistol he the said Robert McEvoy then and there had and held) to, against and upon the said James J. Gregg, then and there, feloniously, willfully and of malice aforethought did shoot and discharge, and that he the said Robert McEvoy with the leaden balls aforesaid out of the pistol aforesaid then and there by force of the gunpowder shot and sent forth as aforesaid, the said James J. Gregg in and upon the chest and in and upon the left side of the abdomen of him the said James J. Gregg, then and there feloniously willfully and of malice aforethought did strike, penetrate and wound, giving unto the said James J. Gregg, then and there with the leaden balls as aforesaid so as aforesaid shot, discharged and sent forth out of the pistol aforesaid by the said Robert McEvoy in and upon the chest and in and upon the left side of the abdomen of him the said James J. Gregg, diverse mortal wounds of the depth of six inches and of the breadth of two inches each, of which said mortal wounds he the said James J. Gregg, from the Twenty first day of April in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and seventy six until the Twenty first of April in the year last aforesaid at Augusta in the County of Richmond in the State of Georgia, did languish and languishing did live, on which Twenty first day of April in the year last aforesaid James J. Gregg at Augusta aforesaid in the County and State last aforesaid of said mortal wounds died.”

“And so the jurors aforesaid upon their oath aforesaid do say that the said Robert McEvoy the said James J. Gregg in manner and form as aforesaid feloniously, willfully and of malice aforethought did kill and murder against the form of the Act of the General Assembly of this State and against the peace and dignity of the said State of South Carolina.

Received in New York on September 15, 1975.

©1975 Richard Pearce

Richard Pearce, a freelance film-maker/journalist, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Pearce and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.