"The employment of the white labor, which is now to a great extent contending with absolute want, will enable this part of our population in a very short time to surround themselves with comforts which poverty now places beyond their reach. The active industry of a father, the careful housewifery of the mother, and the daily cash earnings of four or five children will very soon enable each family to own a servant; thus increasing the demand for this species of property to an immense extent. This will be found to be the case in all those new villages which may spring up upon our rivers and streams under the vivifying influence of factory establishments. And it is as a pioneer in this great work that Graniteville is looked upon with deep interest."

— James Taylor, one of the founding directors of Graniteville, in De Bow’s Review, 1850.

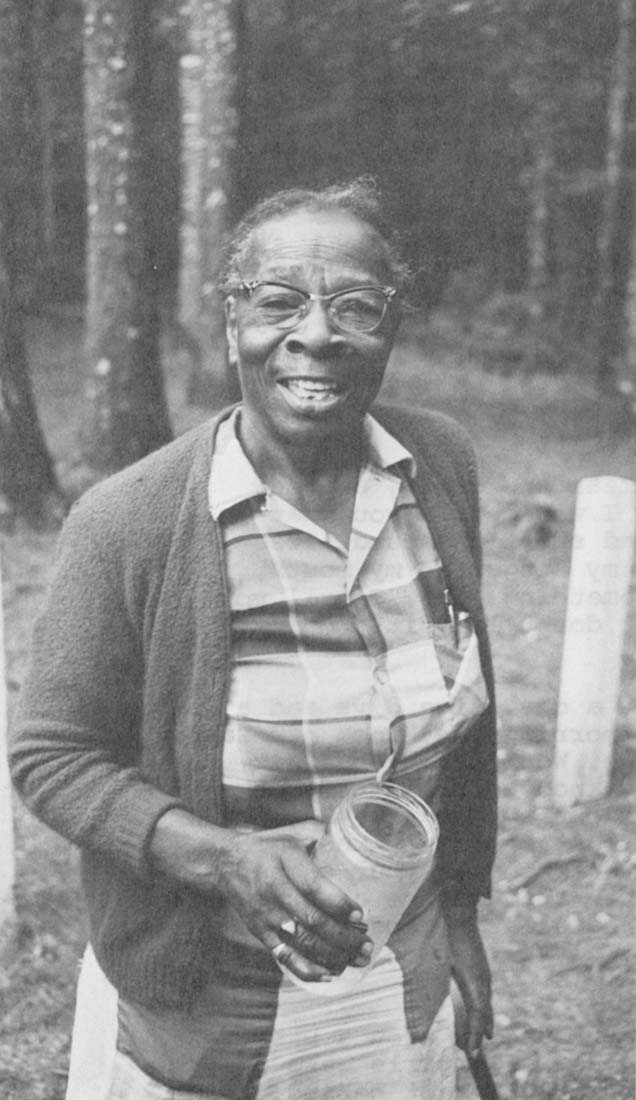

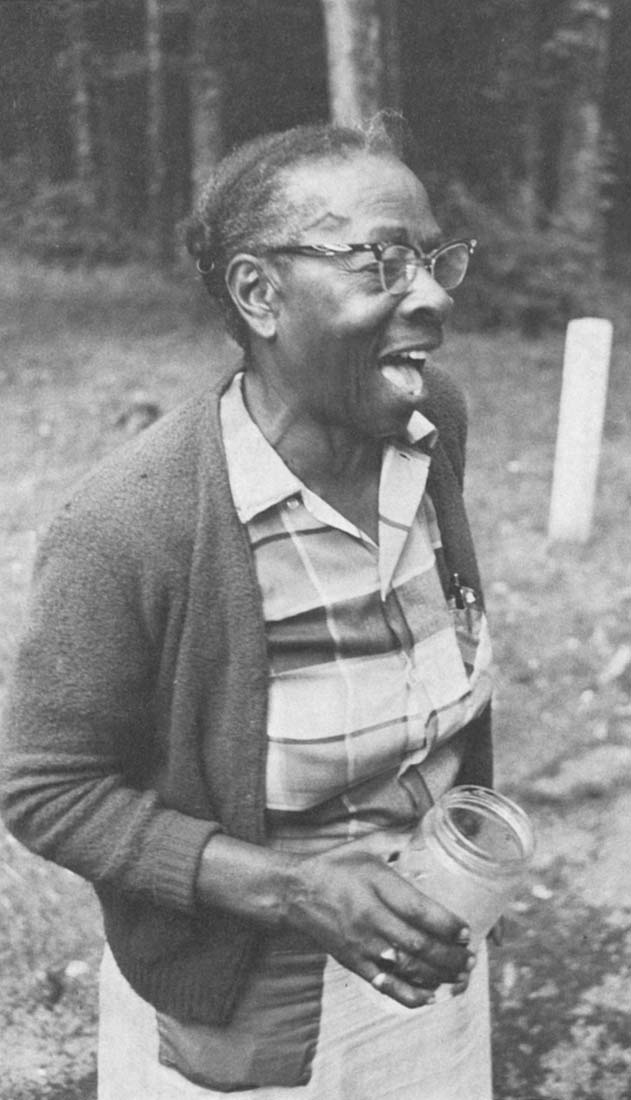

Ollie Whittle’s face breaks into a laugh like a set of china dropped from a second floor window. She leans forward in her green porch rocker with its cushion of scrap foam and throws out her arms to Raymond with a shriek that carries out past his Dodge van onto the four-lane called Gregg Highway that cuts its way like a sutured incision through this black appendage to Graniteville’s factory enclave of gleaming white row houses.

Ollie Whittle’s face breaks into a laugh like a set of china dropped from a second floor window. She leans forward in her green porch rocker with its cushion of scrap foam and throws out her arms to Raymond with a shriek that carries out past his Dodge van onto the four-lane called Gregg Highway that cuts its way like a sutured incision through this black appendage to Graniteville’s factory enclave of gleaming white row houses.

“Whooee!” Raymond, you come home to your old Aunt Whit. Put it right there. You come home.” Whit’s palm flashes up as she takes Raymond’s finger and points it into her outstretched hand. “Everybody comes home that got good sense. Give me some money boy.”

Raymond smiles broadly, and his eyes flick to the stranger on Ollie’s porch, “I am on my way home, and I’ll bring some home when I come home. I don’t have it. I’m trying to get it…But I will have it, miss Whit.”

Softs: “When?”

Softer: “When I come home.”

Pause. Another set of china drops. This time with a howl. “Oh man, are you…? I’m going in there and get me my rifle. You give away all this money to drink liquor with and never give me nothing.”

“When did I do that?”

“I watched you do that when I was living up on the corner. You know your daddy was crazy about me.”

“You know how old I am now, and poor I am? I’m almost forty and poor.” Raymond’s eyes begin laughing silently.

“Oh no, you ain’t no forty.”

Raymond soft: “Thirty-nine.”

Whit softer: “How old am I?”

“I don’t know how old you are, but you’re beautiful.”

Whit smiles.

“I want you to have your daddy’s square cleaned off before you leave.”

“What do you mean? I go there before I come here. I don’t stop nowhere that I go there.”

“You haven’t cleaned it.”

“Don’t tell me it’s not clean. You bet it’s clean. And roped off. All four corners. My spot’s there too. Done named it.”

“No, you guys are going to end up somewhere in New York.”

“No, listen, my roots are here. Sure I been in New York, but this here is my roots, my foundation. This is where I come from. That’s why I’m back here now.” Raymond gives up and bends over with laughter, “Give me something one time in your life. Please. Come on now for one time…”

Whit roars, “You know your daddy frowning on you right now.”

“Frowning?”

“About me. He gone tell you, ‘Raymond, get with some.’ That’s what he’d tell you. Cause he knows he was my boy till he died. And he never would come back to see me, and I wanted to see him so bad…How many children you got?”

“Nooo, they all grown now. I’m forty years old.”

“How many you got?”

“Oh, I had two.”

“Girl and a boy?”

“Two girls.”

“What they do now?”

“Nothing. They just grown.”

“You still working for them?”

“Nooo. They can handle themselves. Nooo, God, they out of my place.”

“Nobody home but you and your wife?”

“That’s all. When you see me, you see the family.”

“Wife with you?”

“Yeah. When you see her, you see her family.”

“What about old Frog? What’s he doing?”

“Doing it to death, really doing it to death. He’s a good hard hustler. He’s always been you know. Everybody’s super except me. I’m the oldest rat in the barn, so I always take the weight.”

“Well if you ain’t brought nothing, you ain’t gonna get nothing here, cause we ain’t got nothing.”

“No, I mean I have friends. I’m looking for return favors now. I’ve been doing them for twenty years. Now it’s my turn.”

“You ain’t done nothing for me.”

“I sold peanuts for you…” Crash and shriek. “And dug the beets.”

Whit roars until the tears pour down her cheeks.

“Do you see that boy keeps giving me his hand? I’m gonna have to go inside and get me my rifle.” Raymond waves goodbye from the van. “Oh I was crazy about that boy’s dad…I didn’t know who that ol boy was…. They must be doing all right I guess up there in New York…. New York people is the biggest liars in the whole world…. Why is it children grow so fast up there in New York?”

Miss Ollie Whittle was born in Graniteville on Feb. 16, 1900. Her father, Jacob Whittle, had moved down into the Valley from up in Edgefield County near Johnson City, where he had owned a small farm and raised cotton. These days Ollie doesn’t talk too much about her father, and her only memento of him is the crumbling remains of a bill of sale to a twenty acre lot on the outskirts of Graniteville that her father once sold to a friend of his named Dugas Davis for $100. But times were hard then and Dugas was his friend, so Jacob never collected the money. Ollie shakes her head smiling. “It don’t make no difference no how. They both dead now.”

On November 28, 1912, Ollie’s childhood came to an abrupt end, on that day her mother took sick and left Ollie age 12 to cook, wash and keep house for a family of eight. Looking back at it now she knows that her mother’s strange illness (the four years of silent agony measured only by the rivers of sweat that Ollie washed from her mother’s steadily shrinking body morning and evening and the bedcovers and bedclothes soaked out in tubs twice a day for four years until that hot still morning in June of 1916 when she awoke to find the tiny white mounds of table salt already poured on the body to help it keep through the wake, her mother all dry and brittle laid out upon the bare springs of the bed floating weightless like a leaf poised for an instant before the invisible breeze set to lift it from its coiled steel branches) was cancer. But to her then it was unnamed and unnameable, a woman’s disease “at the change of life” in a family of men, twelve brothers seven of them grown up and moved away and five still living in the house.

Ollie has never even seen one of her brothers. He had moved away to Florida before she was born, but in some strange way she felt closer to him than to any of the others. Every Spring he would send her a letter saying he was coming up to see her this year and could she send a little money just to help tide him over until then. Every Spring the same letter with the same funny sad promise that they both knew he would never keep, and so every Spring if she had any she would send along a little something to help tide him over. But last year for the first time a letter didn’t come, and so Ollie decided that he too must have passed like all the others and that she alone was left.

“After my mother passed, I wanted to go on to school and study to be a nurse, but my daddy wouldn’t let me. I just had to be the baby instead. And so I said oh shit and went on and married. I didn’t love nobody, at least who I love I didn’t marry. I just married to get grown. My mother died in June when I was sixteen, and in October — the 16th of October — I was married. Married again the 24th of May. But that first one was dead now. I ain’t gonna have no two living. He died. I always marry people that loves me. I don’t marry nobody I love. I ain’t loved neither one of the men I married. They loved me.”

“I was the first colored woman they hired in that mill. I went to the mill in 1917 when they wasn’t no men. Uncle Sam had the men. You know what I did once? One time I didn’t have a job, so when Monday morning come I just walked right up into that mill with my mop and pail and started scrubbing out the alleys you know between the machines. I worked Monday all day, then Tuesday, Wednesday. On Thursday the Second Boss come on, and he thought the First Boss had hired me. And the First Boss thought the Second Boss had hired me, And there I was just working away. I was smart then. I wouldn’t say nothing to nobody. Thursday morning, ‘Ollie, how long you been here?’ ‘Oh man, don’t you come asking me. I been here ever since Monday morning. And don’t you get my time wrong neither cause I’ll tear up this mill. I been here ever since Monday morning.’ And I had been there since Monday morning, but nobody didn’t hire me. I just went up there and went to work.”

“Now if I get tired and sit down you know in the mill, and I see the Boss Man coming around that corner, and I’m just thinking about getting up. I’ll flop right down then. I don’t want you to think I’m scared of you, running from you. Cause I work when I’m working! I do my job. ‘Ollie, what you doing? Taking a break?’ ‘I sure is. You better believe I is.’ ‘Alright.’”

“They always said I was mean and crazy, anybody that fooled around me, because I would tell you what I believe. I ain’t gonna smile and shuffle around, ‘teehee…yassuh…tee-hee’ with my finger in my mouth, saying one thing and meaning something else. I tell you what I mean. You can like it or don’t like it. Don’t make me no difference.”

“I used to work ten hours a day, five days and a half a week, go to work Monday morning and knock off Saturday dinner and get my envelope. Wouldn’t be but six dollars and five cents. And you know a lot of times the boss didn’t send in no social security for you. Well he’d tell you he was taking it out, but you didn’t know. Then when you get out of a job and want to draw your compensation, you don’t have it. You know they got me charged up with three different numbers, and all the good numbers where I made the most time they say belong to someone else. I just don’t know.”

“My job was mopping mostly. But you know I used to go through there where some of the white girls were decent and if the roping fell down or they got behind, I would just help them during my spare time because you know I was learning. But in those days colored people didn’t do those jobs.”

“In those days they had a mule and a dump cart, and in town everybody had closets you know out in the yard. And you would go around, take a shovel and clean out these closets two or three times a week and carry it off. I mean you could smell them closets from here to that sign, but they kept them clean. You went out every other day through the village and shoveled that filth up and carried it off and dumped it.

Miss Ollie Whittle was born in Graniteville on Feb. 16, 1900. Her father, Jacob Whittle, had moved down into the Valley from up in Edgefield County near Johnson City, where he had owned a small farm and raised cotton. These days Ollie doesn’t talk too much about her father, and her only memento of him is the crumbling remains of a bill of sale to a twenty acre lot on the outskirts of Graniteville that her father once sold to a friend of his named Dugas Davis for $100. But times were hard then and Dugas was his friend, so Jacob never collected the money. Ollie shakes her head smiling. “It don’t make no difference no how. They both dead now.”

On November 28, 1912, Ollie’s childhood came to an abrupt end, on that day her mother took sick and left Ollie age 12 to cook, wash and keep house for a family of eight. Looking back at it now she knows that her mother’s strange illness (the four years of silent agony measured only by the rivers of sweat that Ollie washed from her mother’s steadily shrinking body morning and evening and the bedcovers and bedclothes soaked out in tubs twice a day for four years until that hot still morning in June of 1916 when she awoke to find the tiny white mounds of table salt already poured on the body to help it keep through the wake, her mother all dry and brittle laid out upon the bare springs of the bed floating weightless like a leaf poised for an instant before the invisible breeze set to lift it from its coiled steel branches) was cancer. But to her then it was unnamed and unnameable, a woman’s disease “at the change of life” in a family of men, twelve brothers seven of them grown up and moved away and five still living in the house.

Ollie has never even seen one of her brothers. He had moved away to Florida before she was born, but in some strange way she felt closer to him than to any of the others. Every Spring he would send her a letter saying he was coming up to see her this year and could she send a little money just to help tide him over until then. Every Spring the same letter with the same funny sad promise that they both knew he would never keep, and so every Spring if she had any she would send along a little something to help tide him over. But last year for the first time a letter didn’t come, and so Ollie decided that he too must have passed like all the others and that she alone was left.

“After my mother passed, I wanted to go on to school and study to be a nurse, but my daddy wouldn’t let me. I just had to be the baby instead. And so I said oh shit and went on and married. I didn’t love nobody, at least who I love I didn’t marry. I just married to get grown. My mother died in June when I was sixteen, and in October — the 16th of October — I was married. Married again the 24th of May. But that first one was dead now. I ain’t gonna have no two living. He died. I always marry people that loves me. I don’t marry nobody I love. I ain’t loved neither one of the men I married. They loved me.”

“I was the first colored woman they hired in that mill. I went to the mill in 1917 when they wasn’t no men. Uncle Sam had the men. You know what I did once? One time I didn’t have a job, so when Monday morning come I just walked right up into that mill with my mop and pail and started scrubbing out the alleys you know between the machines. I worked Monday all day, then Tuesday, Wednesday. On Thursday the Second Boss come on, and he thought the First Boss had hired me. And the First Boss thought the Second Boss had hired me, And there I was just working away. I was smart then. I wouldn’t say nothing to nobody. Thursday morning, ‘Ollie, how long you been here?’ ‘Oh man, don’t you come asking me. I been here ever since Monday morning. And don’t you get my time wrong neither cause I’ll tear up this mill. I been here ever since Monday morning.’ And I had been there since Monday morning, but nobody didn’t hire me. I just went up there and went to work.”

“Now if I get tired and sit down you know in the mill, and I see the Boss Man coming around that corner, and I’m just thinking about getting up. I’ll flop right down then. I don’t want you to think I’m scared of you, running from you. Cause I work when I’m working! I do my job. ‘Ollie, what you doing? Taking a break?’ ‘I sure is. You better believe I is.’ ‘Alright.’”

“They always said I was mean and crazy, anybody that fooled around me, because I would tell you what I believe. I ain’t gonna smile and shuffle around, ‘teehee…yassuh…tee-hee’ with my finger in my mouth, saying one thing and meaning something else. I tell you what I mean. You can like it or don’t like it. Don’t make me no difference.”

“I used to work ten hours a day, five days and a half a week, go to work Monday morning and knock off Saturday dinner and get my envelope. Wouldn’t be but six dollars and five cents. And you know a lot of times the boss didn’t send in no social security for you. Well he’d tell you he was taking it out, but you didn’t know. Then when you get out of a job and want to draw your compensation, you don’t have it. You know they got me charged up with three different numbers, and all the good numbers where I made the most time they say belong to someone else. I just don’t know.”

“My job was mopping mostly. But you know I used to go through there where some of the white girls were decent and if the roping fell down or they got behind, I would just help them during my spare time because you know I was learning. But in those days colored people didn’t do those jobs.”

“In those days they had a mule and a dump cart, and in town everybody had closets you know out in the yard. And you would go around, take a shovel and clean out these closets two or three times a week and carry it off. I mean you could smell them closets from here to that sign, but they kept them clean. You went out every other day through the village and shoveled that filth up and carried it off and dumped it.

“You know that belt that used to run the old mill from the waterwheel down in the dungeon. Well that belt, Lord, is as wide as that chair, and it broke once and hit me in my back. I didn’t even see it. I knowed something had happened, I thought it was lightning. I said oh God, it wasn’t cloudy when I came in, Whooee! I don’t know whether I laid down or fell down, But pretty soon some white guy came up, and he took one look at me and said ‘Good God, the blood coming out of that woman’s neck!’ (Wasn’t no blood. That guy was just fooling me, making me die for nothing). Well, when he said that I woke up, but I still didn’t know what had happened. It was three o’clock in the morning. I was working both shifts then, day and night, from eight in the morning till twelve at night. You know I likes a heap of money. I’ll try and make a heap of money if I can get it.”

“Domestic, factory, field, any job I could get I’ve done. I can remember how we used to go down into the village through that bottom over there. The moon still up, and you could hear our feet slapping that dirt path in the dark. We’d go over there and cook breakfast for the white folks going to work in the mill at seven o’clock. Oh I got first class pay! I got more than anybody else cause I was a good cook. I got three dollars a week man! The rest of them got two and a half. Whooee! Cause I was a good cook!”

“Wash, iron, tend to the baby, and rake the yard. If they didn’t have no baby, you carried dinner to the mill. We were their servants. They were poor folks. You can be sure the big shots’ wives didn’t work in no mill, like the Supers’ wives. But these little poor factory people that worked in the mill, they had to work. They had to get somebody to stay there with those children and work for them. Somebody had to do it. These people wasn’t paying nothing because they wasn’t making nothing.”

“When I wasn’t in service or in the mill, I used to love to pick cotton! Now you know you used to didn’t see the land laid out like it’s laid out now. Used to be, in the country, every half a mile you’d see two or three homes. There’d be cotton, people farming. I mean you’d have a farm. You’d hire me as a sharecropper. I’d have four or five children, three or four boys, two or three girls. We’d go and make the cotton for you. At the end of the year, you’d take the crop and give us the share. That was sharecropping!”

“And then about the time that cotton was ripe, bunch of us from town here would get together, and you’d send your truck come pick us up, carry us to the field. Shit I been all the way to Wageners. We’d go off and stay one, two, sometimes three weeks what you call ‘shacking.’”

“The Man would take a house like this, nobody in it, and he would go out yonder in the woods and get some pine straw or hay and put it in here. One room for the women and one for the men. We’d sweep the floor up good (might be a snake in there), and then we’d put that pine straw or hay all around. We carried an old blanket or a sheet or something in the summertime and a frying pan, a pot to cook in, some peas, corn, butter beans, collard greens. Man, we was ‘shacking!’”

“There’d be ten or twelve of us. Oh we’d be just like hogs, all the women over here, all the men over there. You and I we’d buy all the groceries together for everybody. We’d buy quarter’s worth of meat, fifteen cents’ worth of sugar, quarter’s worth of flour, fifteen cents’ worth of rice, ‘And you all better get you some of that roll tobacco cause ain’t nobody coming in town till next Saturday.'”

“And those days, that was when the devil was the devil. We’d go to shop at a store. The Man drives up. Now you know we got to stay up in the truck. He didn’t say it to me, and he better not have. I don’t care where we are, whether we in Georgia, I don’t play.”

“’I got a bunch of “n…..”s out here and they want something.’ ‘Well, bring em on in. Tell em to come around to the back.’ (Well that wasn’t gonna hurt me. I’m used to that).”

“’Uh…mister, I want a can of Prince Albert.’ (You try that and you get your brains busted out. You go in that store and ask for a can of Prince Albert! You had to ask for Mister Prince Albert, and I wouldn’t do it).”

“I’d say, ‘…uh…give me a can of that…I can’t read it…give me a can of that one….'”

“‘This?'”

“‘Nawsuh.'”

“‘Well what you talking about?'”

“‘Yassuh, the one with the long coat on it,’ (Mister Prince Albert on a can! I ain’t gonna call no can no mister! I ain’t that weak, and I never did say it). I’d say, ‘give me a can of that…uh….'”

“‘What you mean? Can’t you read?'”

“‘Nawsuh.’ (It was alright to say nawsuh you know in those days. But I tell you I don’t allow no child to talk back to me now, say no to me. I don’t give a damn what his teacher tell him. You talking to me. I call you, you say ma’am. Yes ma’am). Some of those other fools would say it, I never would. You got to say Mister Prince Albert to a can! Now I’ll let you push me just so far, and I know you treating me wrong, but I’ll endure it till I get far enough. Then I don’t care if the judgment comes. Then anything can happen, anything can happen. I bet you think I’m a fool, don’t you. Well I am, I am, but I get what I want. I might not get it when I want it, but I’ll get it. I might not get as much as I want, but I’ll get it.”

“‘Nawsuh.’ (It was alright to say nawsuh you know in those days. But I tell you I don’t allow no child to talk back to me now, say no to me. I don’t give a damn what his teacher tell him. You talking to me. I call you, you say ma’am. Yes ma’am). Some of those other fools would say it, I never would. You got to say Mister Prince Albert to a can! Now I’ll let you push me just so far, and I know you treating me wrong, but I’ll endure it till I get far enough. Then I don’t care if the judgment comes. Then anything can happen, anything can happen. I bet you think I’m a fool, don’t you. Well I am, I am, but I get what I want. I might not get it when I want it, but I’ll get it. I might not get as much as I want, but I’ll get it.”

“Now you go out before the sun get up and get hot. And if you get out there and be out there when it get hot, you can stay out there till twelve or one o’clock. But don’t you knock off and go in yonder and get you a stick and knock a few branches down and sit down under there and eat your dinner in the shade and drink you some water and smoke you a cigarette and if you got a headache take you a B.C. or a Stanback, cause if you do, you can’t come out into that sun again. You just can’t stand it. You got to wait way down till about 6:30 before you can go back out. When you out there, stay out there.”

“Now me I just sit down and rest, but not too long. Not enough to get lazy. But sometimes I have to get in behind the rest of them. Somebody gone in the scuppernong vine. Somebody gone up to the store to get him a drink and mess around. Alright now, get on out here. I didn’t haul you out here to lay around the woods.”

“And they say, ‘0h whit, it’s hot.'”

“I say, ‘If you don’t come out here, I’m coming in there with me a smart ‘simmon stick.’ (Persimmon stick you know is tough like a sugarberry switch).”

“And they say, ‘0h Whit, we coming. You just gonna kill your fool self. Money be here when you gone.'”

“And then one of them say, ‘Ssshh, don’t tell her, I’m gonna hide. Tell her I’ve gone to the store.’”

“And I say,‘Where is so-and-so’I done heard what they said)?”

“‘They gone to the store.’”

“I say, ‘Okay, I’m gonna find me two three brickbats, and I’m gonna knock that store door open right out here into these woods.'”

“Then that one jumps up from where he’s hiding, ‘0h Whit, don’t you throw them out here.’ Whooee! Oh I had me a lot of fun, made me a lot of friends. I let them treat me any kind of way till I get tired, then they had to walk the chalk line, any color and anybody and any kind.”

“I was a good cotton picker in my time. Everybody used to come here looking for me. I had women, men, girls and boys all go out shacking with me. And we’d pick cotton. We would work. I’ve even had a crowd out there picking cotton and pulling forty middle of the night, moonshine bright like day. (I been snake bit three times. I was crazy. Snake ought to have bit me then. No, he wait till I come out there picking blackberries). I remember when we went to getting a dollar a hundred, Man, that was something! Then we went up to a dollar and a half. Whooee!”

“You know they ain’t saving nothing by these machines. When that big cotton picker come, it just go in there and pull off cotton balls, cotton stalks, cotton leaves, cotton everything and then scatters it all over the ground. You leave half of it on the ground. And you know that machine can’t pick it till the leaves die, so you got to hire a airplane. Pay him a dollar a minute. Come down and spray the rows to kill them leaves. A dollar a minute. It seems like those machines began coming in just about when things went to getting good. You know white folks didn’t used to pick no cotton. Now they beat you in the fields today.”

“But I’ll tell you what. You ride out through Breezy Hill and go into Augusta, come back any way you want, then out Pine Log Road to Aiken, you don’t see nothing the white man got, the Negro ain’t got. Nothing. Automobile, any kind, Cadillac, white Rolls Royce, a boat. ‘Cuff’ he work up there in that mill and drive the same boat you drive. Got the same kind of house you got or a little better. Honey we are on top. Them that’s living, that is. Now I ain’t, but that’s cause I’m dead. I just ain’t cold. Whooee. This thing sure come down. Broke right down where we can handle it.”

“Everything’s on equal now. Just what they pay the white man or the white woman, they pay to the Negro. Everybody got forty-eight to fifty-two frames now. I don’t care if you look like snow or look like black ink. Flesh is flesh, and blood is blood. You go out there and cut a man look like soot and cut one look like snow and put that blood together, you don’t know which is the white blood and which is the black, do you? And on top of that, if you don’t hire me here, you hire me over yonder. If I don’t work over there, I can come right here and work. And I tell them over there, ‘To hell with you man. This ain’t no slaveytime. Slave time never will be back here.'”

“But you know like with that union business, there’s some people are two-faced. That’s what I can’t stand. You’ll tell the union man you want it, and then you’ll tell the boss on the job you don’t want it, that you’re faring alright. But what you don’t know is that you got to produce your name and your signature and face it. Some people think they’ll fire you. They can’t fire you cause you sign up for a union. But a fool don’t know that. ‘Well I got to live…I done made it this long. I ain’t got but a few more to go….’ Fool! Anything good for me I want it now. Right now, in my day, not after I get cold.”

“You got to stand up and let them people know you standing up. Let them know you mean what you say. You can’t throw no rocks then hide your hand. You got to say, ‘Hey! Yes, I’m for the union. Tell everybody on the press I’m for the union.’ You want to sign that agreement and don’t want nobody to know it. Want to just slip into it. How you want to slip in and get blessed? Let the world know where you at.”

“You know they wouldn’t want a fool like me in those mills nowadays anyway. Cause I tell you what’s right and what’s wrong and stick to it. I don’t care nothing about your Gatling guns, machine guns, your National Guard or nothing else. But I ain’t got time to stir up nothing now. All I want is a living. I ain’t looking for the killing cause God gonna do that.”

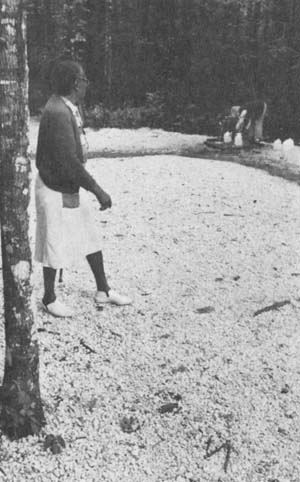

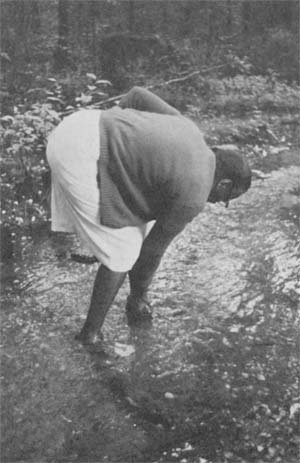

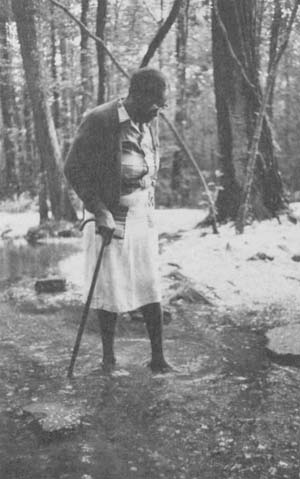

“I guess the only thing I got to say is you got to just do your duty…and drink that good old spring water. You know, healing water. I wouldn’t take nothing for it cause it has saved me many a doctor bill . I believe it’s kind of holy water. God ain’t going to spew nothing out of the ground like that for years and years for no reason. And it ain’t nothing you draw out of no well! It’s  six or seven spigots. Run all the time, just run all down those spigots and you catch it. I bet that water been here since slaveytime. They tell me they used to sell that water once. You know it couldn’t be fake. Do you think I’d leave home, go all the way down there and get that water when I can get water right here in my kitchen? Run all the time. And people there from everywhere getting it. Bring jugs and everything, just catching that water. You see that big old jug in there? Well I got all kinds of smaller ones too. Just catching that water. You go there tonight you’ll find it. That thing just running all the time, a healing spring just flowing. People there with jugs, trucks, cars, everything. Day and night. It must be good. They got some little white rocks there all in the water and the water just run down all the way down and I walk in that water. But I can’t walk on those rocks cause my feet’s tender. Got to find me some old pieces of shoes and walk on where there’s some bottom to it. I left them down there behind a tree. I know somebody done got them by now, Whooee! Put on them shoes and walk out there in that water. You know there’s a history of it down there…that healing spring. There’s a history of it. But I ain’t had the time…I ain’t had the time to read it cause I didn’t care, All I wanted was the water. I didn’t want the history, Whooee, I’m crazy ain’t I? I didn’t want the history. All I wanted was the water.”

six or seven spigots. Run all the time, just run all down those spigots and you catch it. I bet that water been here since slaveytime. They tell me they used to sell that water once. You know it couldn’t be fake. Do you think I’d leave home, go all the way down there and get that water when I can get water right here in my kitchen? Run all the time. And people there from everywhere getting it. Bring jugs and everything, just catching that water. You see that big old jug in there? Well I got all kinds of smaller ones too. Just catching that water. You go there tonight you’ll find it. That thing just running all the time, a healing spring just flowing. People there with jugs, trucks, cars, everything. Day and night. It must be good. They got some little white rocks there all in the water and the water just run down all the way down and I walk in that water. But I can’t walk on those rocks cause my feet’s tender. Got to find me some old pieces of shoes and walk on where there’s some bottom to it. I left them down there behind a tree. I know somebody done got them by now, Whooee! Put on them shoes and walk out there in that water. You know there’s a history of it down there…that healing spring. There’s a history of it. But I ain’t had the time…I ain’t had the time to read it cause I didn’t care, All I wanted was the water. I didn’t want the history, Whooee, I’m crazy ain’t I? I didn’t want the history. All I wanted was the water.”

©1975 Richard Pearce

Richard Pearce, a freelance film-maker/journalist, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Pearce and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.