ARMONK, N.Y.–Working for IBM these days is not just a job experience. It’s also a welfare experience. The company not only provides handsome pension and health insurance for its workers and their families, but also does the following: offers health classes and physical examinations, helps organize van pooling to reduce employees’ commuting costs, pays for some of the costs of adopting a child, provides pre-retirement counseling, and supplements government health insurance for its retired workers. But these benefits pale before one other: since the Depression, IBM has not laid off anyone.

IBM is exceptional in the breadth of its benefits, but its experience is hardly unique. Private welfare is now pervasive in the United States. Major employers–companies, the federal and local governments–have become mini welfare states, providing vast health, pension and fringe benefits for their workers.

It is one of the most striking of postwar phenomena. Workers have come to expect generous health and retirement benefits and more job security. Firms have increasingly regarded the amalgam of fringe benefits–the most conspicuous and costly aspect of private welfare–as a management tool. To IBM, it inspires company loyalty, reduces turnover, cuts training costs and maintains stability among the salesmen, engineers and researchers needed to service IBM customers and develop new products.

But, if private welfare has refashioned American capitalism, it has been a mixed blessing. For workers, it has–much as anticipated–bound them to their companies. But the dependence has not been entirely wholesome; like many dependencies, it continually risks turning into a love-hate affair. At the same time, the advantages to the firm have diminished while the costs have increased. The favorable effect on worker morale is no longer clear, in part because many fringe benefits have existed for so long that they are taken for granted.

Private welfare may also have imposed a considerable cost on the economy. What makes sense for the individual firm may make less sense for the nation. It makes sense, the late economist Arthur Okun argued, for firms to extend what he termed an “invisible handshake” to their workers. The handshake included, in Okun’s view, an informal commitment to be “fair” and to try to maintain workers’ living standards against erosion by inflation. But the implication, Okun said, is that inflation–once started–becomes deeply embedded, because one year’s wage and salary increases shadow the previous year’s inflation.

Thus, only prolonged stagnation exorcises inflation. It does so by raising unemployment (which lowers workers’ expectations), creating surplus industrial capacity (which puts downward pressure on prices) and squeezing profits (which diminishes employers’ ability and willingness to comply with the “invisible handshake”).

But whatever the costs, private welfare has become a permanent part of the American landscape, reflecting major economic and social changes. Employment has become increasingly concentrated in large organizations. As employers grew in size, they could no longer rely on personal contact and trust between managers and workers. Rules, personnel departments and fringe benefits emerged in their place. Generally tight labor markets since World War II induced firms to enlarge their benefits in order to remain competitive. Labor unions generally bargained for generous fringes and created a model for non-union employers–either out of admiration or fear of unionization–to emulate. The prod was substantial. One study by Harvard economist Richard Freeman estimated that unions generally negotiated one-fourth to one-third more in fringe benefits than management at comparable non-union firms offered.

The concentration of employment is astonishing. By the late 1970s, more than three quarters of Americans working for private firms were employed by companies with 20 or more employees; more than two-thirds worked for firms with 50 or more employees, and more than half worked for companies with 500 or more. Government and non-profit employment was, if anything, probably more concentrated. A list of the largest employers in the country underlines just how massive they are:

| U.S. Government | 2,895,000 (civilian) |

| American Telephone | 1,040,000 |

| General Motors | 741,000 |

| Ford | 405,000 |

| General Electric | 404,000 |

| IBM | 355,000 |

| Sears Roebuck | 337,000 |

| ITT | 324,000 |

| New York (city) | 319,000 |

| California | 310,000 |

Finally, the expansion of government also indirectly encouraged private welfare. As tax rates rose, it became increasingly attractive–for both companies and workers–to channel more and more compensation into fringe benefits. The Internal Revenue Service exempts most fringes (such as employer-paid health insurance, pensions and vacations) from income taxes.

The company pays a worker’s health insurance, but the payments aren’t counted as income. This creates an inducement for the company to buy the health insurance for the worker. Consider a worker facing a 30 per cent tax rate. With an extra $1 of income, the worker could only buy $0.70 worth of health insurance, because taxes take 30 per cent. If the company buys, an extra $1 purchases $1 worth of health insurance. By channeling more of total compensation into fringe benefits, companies can achieve higher living standards for their employees.

A Special Place to Work

Few companies better exemplify the resulting system than IBM. Employees are bombarded with pamphlets, booklets, computer printouts and video tape presentations designed to make them feel that IBM is a special place to work and that the company cares about them. There are pamphlets on financial planning, fringe benefits, pre-retirement planning, relocation, career advancement and ride-sharing. The list goes on. The company, says one video tape presentation shown to most new employees, is

“concerned about the dignity and rights of each person in the organization, and not just when it is convenient to (be) so. Since its earliest days this special feeling about each individual has helped the company grow and earn the loyalty of its employees and its customers. This concern is riot an empty credo, for management strives diligently to avoid status symbols and inequality.”

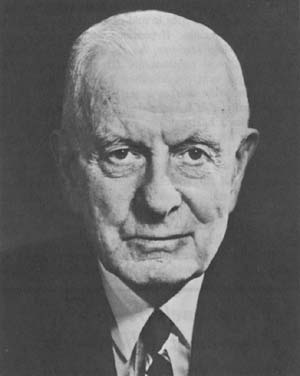

What has happened at IBM-and many other firms, too–is that beliefs that were once vaguely felt in the 1930s have become thoroughly institutionalized. In IBM’s case, the policies came from Thomas J. Watson, the company’s first chief executive officer.

A friend once described Watson as a “benevolent despot.” He grew up on a farm in New York state, where the important values he learned were “to do every job well, to treat all people with dignity and respect, to appear neatly dressed, to be clean and forthright, to be eternally optimistic and above all, loyal.” These were the values he sought to instill at IBM.

Watson likened IBM to a family. He personally adopted a policy of no layoffs, maintained it through the Depression and, although not a formal guarantee, it has continued to this day. (In the 1974-75 and the 1981-82 recessions, the company encouraged early retirement, promoted the use of accumulated vacations and relied on attrition to avoid layoffs. In addition, workers voluntarily transferred to new jobs at other locations.)

Watson was an inveterate corporate booster. There were company dinners, company country clubs, company trips (in 1940, the firm brought 10,000 workers to the New York World’s Fair) and company songs. One of the songs went:

With IBM Machines

We’ve Got The Finest Means

For Brightly Painting The Clouds With Sunshine

Some of Watson’s quainter practices (like the songs) have disappeared, but the spirit remains. Watson always wore a white shirt and insisted that others do likewise. He rarely took off his jacket. “We meet people for the first time, and they judge the company by our appearance,” he said. “The man who wishes to be a success in business must dress the part.” The white shirt is still the predominant corporate uniform at IBM, and many of Watson’s other routines have been preserved and expanded. IBM salesmen, if they make their quotas, still belong to the Hundred Per Cent Club and are treated to a special trip. IBM scientists can win special company fellowships entitling them up to five years to do their own research at company expense. What Watson sought to create–and largely did–was a corporate culture. Those at IBM call themselves (and are called by outsiders) IBMers; workers’ sense of identity and self-esteem stemmed increasingly from the work place.

In part, fringe benefits constitute the glue that gives cohesion to the corporate culture. Those benefits have soared in the past 30 years. There wasn’t any hospitalization until 1946, and the first plan limited coverage to employees’ children only to the age of 19; the limit now is 23 for dependents. Major medical insurance, covering most doctors’ bills, didn’t appear until 1956, and, over the years, the plan has expanded to include charges by podiatrists, psychologists, speech therapists, Christian Science practitioners and mental health clinics. Retirement and vacations have grown progressively more generous. In 1945, when the retirement plan was first introduced, employees received a pension after reaching age 65 and accumulating 11 years of service; pension benefits generally equaled 60 per cent of salary. Now, anyone with 30 years of service can retire with full pension benefits; benefits have risen to an average of 70 per cent of final salary. As late as 1955, employees received a maximum of three weeks vacation and needed 10 years of service to earn that. Current employees receive three weeks vacation after four years, four weeks after nine years, and five weeks after 19 years.

Bombarded with Messages

Beyond the financial bonds, IBM constantly attempts to reinforce the sense of attachment and security. Since the late 1950s, it has annually conducted a massive survey of all IBM workers to gauge morale, identify pockets of discontent and test new ideas for fringe benefits and personnel policies. To that has been added the growing stream of letters, pamphlets and video tape presentations. Says Walton Burdick, vice president for personnel: “People are bombarded by messages in our society today. From the moment you rise in the morning to the moment you retire at night, you’re being told–through various forms of media–what to do, what to buy, who to vote for. We need to compete more with that–to communicate more with our employees. Our first constituency should be our employees.”

There is an insistent effort to personalize and overcome IBM’s size (in 1981, the company was the eighth largest U.S. industrial corporation). Think, the company magazine, regularly features stories about individual employees (A sample: “Out of the Migrant Farm Fields”–a story about a Mexican-American IBMer). Beyond these superficial trappings, IBM managers–the roughly 10 per cent of IBM’s payroll that has responsibility for other workers–have standing instructions to make individual gestures to workers who either have done exceptional work or are experiencing acute illness or family tragedy.

“I spent 32 years of my life at IBM,” one former executive recalled. “In 1969, my wife had a serious accident. Then, within a month, her stepfather died in Arkansas. I was in California. The company arranged for me to go to Arkansas and flew my wife and three daughters to Arkansas in a company jet. They (IBM) were big enough to afford it and small enough to do something about it. It meant a lot to me.”

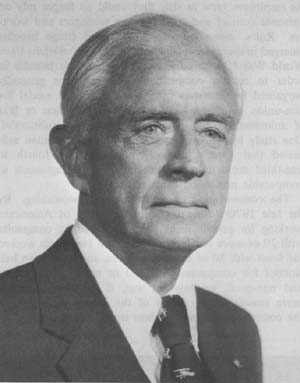

But there is another side to the bargain. “Our early emphasis on human relations was not motivated by altruism but by the simple belief that if we respected our people and helped them respect themselves the company would make the most profit,” Thomas J. Watson Jr., who succeeded his father as chairman, once said.

More crudely, the bargain is this: in return for the cocoon of security and concern, the company expects its workers to be loyal and intense; to strain–if they are salesmen–to meet their quotas; to give up weekends when needed; to work “reasonable amounts of overtime to help protect…job security.” (But like many things at IBM, even these rigors are regulated. On overtime, a top executive has written: “However, excessive overtime may be costly and may cause employee dissatisfaction as a result of decreased income when overtime is terminated. In addition, it may have mental effects on the employee’s health and family relationships. Therefore, guidelines have been established to limit and control the amount and duration of overtime for each employee.”)

This part of the bargain can be, at times, brutal. Watson, Sr. periodically administered blistering tongue-lashings to subordinates and, in this, he also set a tone that has survived. Lecturing at Columbia University in the early 1960s, his son admitted that the firm applied “harsh” measures to laggard managers that stripped them of a “fair amount of dignity.” Salesmen who lose accounts must repay commissions that they’ve already collected–a penalty that is potentially so stiff that it has forced some to leave the company. Lower and middle level executives feel intense pressure. “What they hold out to management types is rapid advancement,” said one ex-IBM manager. “There’s an awful lot of lateral movement that’s billed as promotion, to keep you interested. The worst thing that happens to middle managers is to be passed over.”

The Company Shrink

Every worker at IBM, no matter how low, is given an annual “performance plan” that attempts to set out duties, responsibilities and expected accomplishments. There is an accounting once a year; managers and subordinates sit down individually to review performance. There is a “Manager’s Guide to Employee Development” that tells managers how to deal with their workers. As a practical matter, though, “people don’t get fired very often.”

“Firing someone is a very big deal,” said the ex-IBM manager. “You give the guy a performance plan, he’s not making it, you bring him in and say, ‘Charlie, I’ve got to tell you…’ You’ve got to place him on an improvement plan–it’s got to be signed by you and shown to him. It’s monitored, and he can get counseling along the way. He can go to the company shrink.”

The protection is broader. IBM has changed with the times.

“The old view of IBM–I’ve been moved–has given way to some new sociological and economic realities; working wives, the disinclination to be moved so often, the high interest rates (which make workers less willing to lose older mortgages)…There’s a certain society, camaraderie, social system that you can call on for advice,” said the ex-manager. “If you have trouble in your career, you’re kind of insulated. You have all the stresses that the company puts on you, but, because of full employment and the benefits, you have a sense of security. They’ll pay for a psychiatrist for you, your kids, your wife…”

As practiced at IBM-and countless other firms–private welfare undoubtedly represents one of those timely reforms that have made capitalist institutions more humane and tolerable. It has subtly altered the nature of work relationships by giving employers broader social responsibilities. To some extent, employers have supplanted churches, political machines, neighborhood organizations and private charities as the focal point for the satisfaction of mass wants and the relief of individual distress. In the process, American business has fundamentally reoriented itself. Until the late 1940s, large segments of industry steadfastly opposed the expansion of fringe benefits. In 1949, the Inland Steel Co. went all the way to the Supreme Court in an unsuccessful challenge to unions’ insistence that fringe benefits be a mandatory subject of collective bargaining.

For most of the postwar period, fringes consistently grew faster than basic salary; in the early 1950s, they were equal to about a fifth of basic salary costs and, three decades later, about twice that much.

What has become increasingly clear, though, is that this system has not realized many of its presumed benefits. Liberating workers from many of the traditional economic insecurities was expected to strengthen worker satisfaction, making companies more productive. What held for individual workers and companies was also assumed to apply to the entire economy: if the parts worked more smoothly, then the whole must benefit, too. There was an unstated belief that growing corporate welfare would not only prove compatible with economic efficiency, but might actually improve it.

The actual results have been considerably more ambiguous. Private welfare–like government welfare–has created inevitable dependencies. The worker becomes more dependent on the employer, but, at the same time, employers are constrained–both formally and informally–by the welfare obligations they have assumed. For companies, welfare obligations have become increasingly costly, while the presumed advantages of greater loyalty and work effort have apparently diminished. Individuals have been relieved of many economic insecurities, but they have also lost much control over their own lives to their employers.

Employer pensions offer a case study of the opaque interconnections. In effect, Americans have transferred much of the responsibility for personal savings from individuals and families to the corporation. After housing, pensions now represent one of the largest–perhaps the largest–form of middle class saving. In 1980, private pension assets (including those of government pension funds for government workers) totaled $729 billion. Other forms of savings appeared superficially to be large. For example, consumers’ time and savings deposits totaled $1.3 trillion, the value of individual stock holdings exceeded $1.1 trillion and other securities (bonds, U.S. Treasury securities) amounted to nearly $600 billion. But much of this wealth is highly concentrated. Up to half the corporate securities are crudely estimated to be held by no more than two per cent of the population. Pension assets are almost surely more broadly based. Many Americans are saving remotely and invisibly; their employers are doing it for them.

The practical effect, though, is that many workers can’t easily quit their jobs in mid-career without suffering a huge loss in savings. If pensions were treated simply as floating savings accounts, the penalty would not exist. But, in fact, most pensions are far more complicated. About 70 per cent are so-called defined benefit plans, which promise the worker a certain benefit on retirement. Usually, this is calculated from a formula based on the worker’s final pay (or average pay over, say, the last three or five years) and the number of years of service. Leaving early greatly diminishes the pension benefit (presumably, the worker’s salary would have been higher in later years, if only to reflect inflation). Not surprisingly, studies of major companies indicate that workers respond rationally; they remain to realize the full benefit (or near it) of their savings. Companies used the plans as tools to stabilize their work force.

Only belatedly have employers and workers begun to recognize the drawbacks. For employers, holding onto workers too long can often be as costly as not holding onto them long enough. “It’s the 40 to 55 year old group that’s the toughest problem,” says one personnel executive. “If the person isn’t motivated or hasn’t kept up technologically, they’re a big challenge. They can’t retire, and they’ve got so much invested they can’t leave.”

Companies can escape this squeeze, but only by raising their pension costs and offering special “incentives” for early retirement. Many firms have done this, but it becomes more difficult as the work force grows older. As for workers, they can find themselves trapped in jobs they don’t like and would prefer to leave.

Similar conflicts have arisen across the spectrum of corporate practices; the welfare ethic and the work ethic don’t always march in lockstep. Employers often find themselves struggling between the dictates of their personnel system and the circumstances of individual cases. Workers get caught in the same conflict. Merit pay is a good example. Over the years, the prerogatives of seniority have eroded the importance of merit pay. Although firms say they pay and promote on the basis of performance, academic studies have found otherwise. The “principles of seniority, automatic progression and equal treatment” have often predominated.

Firms have apparently felt that the advantages of rewarding better employees were outweighed by the possible disadvantages of alienating other workers who felt they were the victims of favoritism, discrimination or “unfair” treatment.

But many companies are no longer so certain. By the late 1970s, many middle-managers felt frustrated by the restrictions of modern personnel management; they saw it as a form of civil service straight-jacket, which inhibited them from disciplining or rewarding workers. When Fred K. Foulkes, a business professor at Boston University, surveyed non-union firms, he discovered significant dissatisfaction by supervisors and line managers over their authority.

“Personnel people sometimes make things difficult,” said one supervisor. “They stand behind the employee. It is hard to get rid of a person after three months. They make sure there is very good documentation. Personnel always takes the view of what is fair and just for the employee.”

The 1981-82 recession has apparently reinforced these doubts. Facing squeezed profits and high unemployment, some firms (just how many is impossible to say) have begun to restore more genuine merit pay. “In the past six months, the feeling of entitlement has gone away,” said Alan Johnson, a compensation specialist for the management consulting firm of Hewitt Associates. “Companies are now using performance pay with a vengeance. Some people will get nothing (as an increase), some five per cent and some 10 per cent. There’s limited dollars. I think companies are finding that it has tremendous advantages for morale, motivation and productivity.”

The central contradiction embedded in most private welfare involves Americans’ insistence on individuality and their expectation of greater security. Providing security almost inevitably means compromising individuality. People get placed in groups: groups for health plans, groups for pension plans, groups for seniority systems. Individual choice, reward and responsibility diminish in importance. The growing significance of fringe benefits–simply another form of compensation–means that workers have less disposable income to spend as they see fit. The emphasis on seniority pay and dismissal systems reduces individual reward and responsibility.

The conflicts were not immediately obvious. Reacting to the Depression, workers assumed–naturally and logically–that greater economic security enhanced their individual choice and opportunity. Enlightened companies assumed that a contented work force would be a better one.

To a large extent, time has demolished this neat equation. A younger generation of workers, conditioned by decades of high employment and large fringe benefits, has come to expect them, while simultaneously believing that it owes the employer much less in return. Many new workers are no longer so willing to subordinate their personalities and identities to their employers’ needs. “The young workers don’t feel the same loyalty,” said one former IBM executive. “In 1948, you believed the company could do no wrong. It was a high-flying company. The old man (Watson Sr.) was still alive. In return for this, the company gave us a lot. The guys in the 1970s came in with a different attitude. They were young men or women in a hurry. They thought they knew what they wanted. They weren’t necessarily willing to move if the company wanted them to move.”

In another sense, private welfare was almost bound to be disillusioning. The efforts of individual firms–and, sometimes unions–to protect their own workers simply create economic problems for the society as a whole. Economic costs are transferred from the individual firm or workers to the economy.

Economist Okun identified one mechanism. Firms that committed themselves to maintaining the “real” purchasing power of their workers’ wages tended to perpetuate inflation. Union contracts that included cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) clauses had the same effect. Supplementary unemployment benefit (SUB) programs in steel, auto and other heavy industries are a particularly telling example of the mixed results. Highly volatile demand in these industries meant that workers were often subject to layoffs. The SUB payments–an extra payment on top of the normal unemployment benefits–were an understandable attempt to stabilize workers’ income (and the incomes of the communities where they lived) over the course of the business cycle. But, by insulating workers from the effects of unemployment, SUB programs also acted to maintain high wage inflation.

Individual companies’ efforts to preserve a “full employment” policy often suffer from the same. defect–they can only succeed by transferring the problem to others. IBM’s formula for sustaining full employment, for example, involves a policy of keeping the work force slightly smaller than the company’s projected needs. In prosperous times, IBM customarily bridges the gap in three ways: by increasing the overtime of its own workers, by hiring more temporary outside workers, and by contracting more to outside firms. In leaner periods, the operation works in reverse. Overtime, temporary employment and outside contracting are reduced. This, in effect, creates a game of musical chairs. All of IBM’s career employees may be able to sit down, but the same is not true for everyone dependent on IBM work.

The ambiguous accomplishments of private welfare serve as a metaphor for much of the postwar economic experience. In many respects, the country has succeeded in attaining goals that, in the 1930s and even the early 1950s, seemed almost beyond grasping. But reaching and surpassing them did not bring the anticipated satisfaction. Yesterday’s vision transformed into today’s reality lost much of its luster.

©1982 Robert J. Samuelson

Robert J. Samuelson, economics reporter for the National Journal, is investigating changes in the U.S. economy since World War II.