George Hatsopoulos had a vision when he graduated from MIT 27 years ago. He wanted to change the way the world makes electricity.

Starting business in the proverbial garage–it was a few miles away from MIT in Belmont–he theorized that, properly heated, some materials could give off electrons (that is, produce electricity) to a nearby receptor. If he could only find the right material, he would dispense with huge steam generating plants. There would be an immense savings in raw energy and a giant leap in economic efficiency.

Nearly three decades later, it still hasn’t worked out. But on the road to failure, Hatsopoulos has built a company with sales of roughly $250 million and hopes of reaching $1 billion. Thermo Electron Corp. is large (3,000 employees), has multiple plant operations (about 20), operates internationally, and sells a diversified group of goods and services. At the same time, it remains a “high tech” firm. Its headquarters sits just off Route 128, the fabled highway around Boston that attracted so many high technology companies in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Thermo Electron sits in the great twilight zone of American business. It is not yet an established giant–tradition bound and wealthy–but it has definitely graduated from the ranks of toddlers. (It ranked 739 among Fortune’s 1,000 largest industrial firms in 1981). It is thus an almost ideal specimen for examining the problems of American business. Thermo Electron is large enough to experience many of the problems of size, yet new enough to remain preoccupied with growth. And in its brief history can be found many of the central dilemmas of the modern American corporation, chief among them the corporation’s need for order and the inherently disorderly nature of innovation.

The problem of business is, of course, the underlying problem of the American economy. For, in some respects, business is the central disappointment of the postwar economy. The postwar economic vision–especially as it came to be appreciated in the 1960s–rested on the conviction that business served as a bottomless source of increasing wealth. The corporation became the primary vehicle by which society raised its living standards, maintained global economic supremacy, and promoted new forms of well-being–less pollution, safer products, less racial and sexual discrimination.

There was a remarkable and rarely mentioned consensus about the productive capacity of American firms. Most assumed that modern American corporations could meet society’s demands without sacrificing their essential efficiency. When it turned out that corporations could not produce endless wealth, then almost everything else became more difficult.

The nature of the economic question changed. The assumption that corporations would produce increasing wealth suggested one set of social and political issues. What should be done with this wealth? Who should get it? But if business could not automatically produce greater wealth, then new questions arose. Why not? What could be done about it? How did the system work?

Big Business

To say business, of course, is to simplify. It is not a monolith. No one knows precisely how many businesses there are: 15 million, give or take half a million or so, is a good estimate. The overwhelming reality about business in the United States is that it is heavily concentrated in organizations that are extraordinarily large. If 500 employees is taken as the cutoff point between small and large, then big companies account for about three-fifths of the nation’s output and the proportion has been increasing slowly over the postwar period. In addition, large companies perform virtually all the nation’s research and development. In 1979, more than 90 percent of the $38 billion spent by firms on research and development was done by 1,400 firms with more than 1,000 employees.

Among the largest firms, concentration hasn’t increased significantly in the postwar period and what gains were made tended to be offset by two other changes–the decline in the relative importance of manufacturing and the growth in imports, which limited the market power of U.S. firms.

What this apparent stability obscures, though, is huge growth and change. As the economy expanded, many of the biggest companies had to grow bigger all the time just to maintain their relative market share. They were also becoming more diversified. As late as 1949, according to one study, roughly 70 percent of the nation’s largest industrial firms were engaged in a single or dominant business. Twenty years later, that had declined to roughly a third, and it is surely lower today.

Moreover, the corporate lineup isn’t constant. New firms, like Thermo Electron or Apple Computer, begin and grow: old ones whither and die. Some are merged out of existence and others are created by being split off from a parent company. Seventy-two of Fortune’s “500 largest industrials” were swept off the list between 1966 and 1970 alone. In 1981, 27 companies joined the top 500. The bumping and cannibalism is constant. Of the top 10 companies in 1909, only one–Exxon, then known as Standard Oil of New Jersey–remains.

Thermo Electron has many of the attributes of older and bigger firms. It strives for orderliness and certainty, while the essence of innovation–new technologies, products and new markets–is often disorderliness and uncertainty. Modern management attempts to bridge these contradictions, but only partially succeeds. In some respects, the Thermo Electron story is an eloquent affirmation of this basic tension.

Along with Hatsopoulos, most other top executives are engineers and, indeed–because so many of them either taught or graduated from MIT–the senior management constitutes something of an MIT mafia. Most of the top executives have worked together since at least the late 1960s. Everyone calls Hatsopoulos by his first name.

The place has about it the informal air befitting a new and smaller operation, yet until the recent recession, the firm was growing at an average annual rate of nearly 40 percent–far in excess of most companies. Despite recent reverses, Thermo Electron is still considered a leader in energy efficient equipment and sophisticated instrumentation.

Research and development was, and is, the company’s soul and hope for growth. The theme of technological opportunism runs constantly through the firm’s short history. Hatsopoulos’ original idea about revolutionizing electricity generation–known as thermionics–proved correct. There was considerable interest in practical applications: the Navy envisioned compact, efficient generators for nuclear submarines; the Army wanted small, silent generators to run battlefield command posts; the National Aeronautics and Space Administration needed light generators for satellites. All this brought R&D contracts and additional outside investment from private venture capital groups.

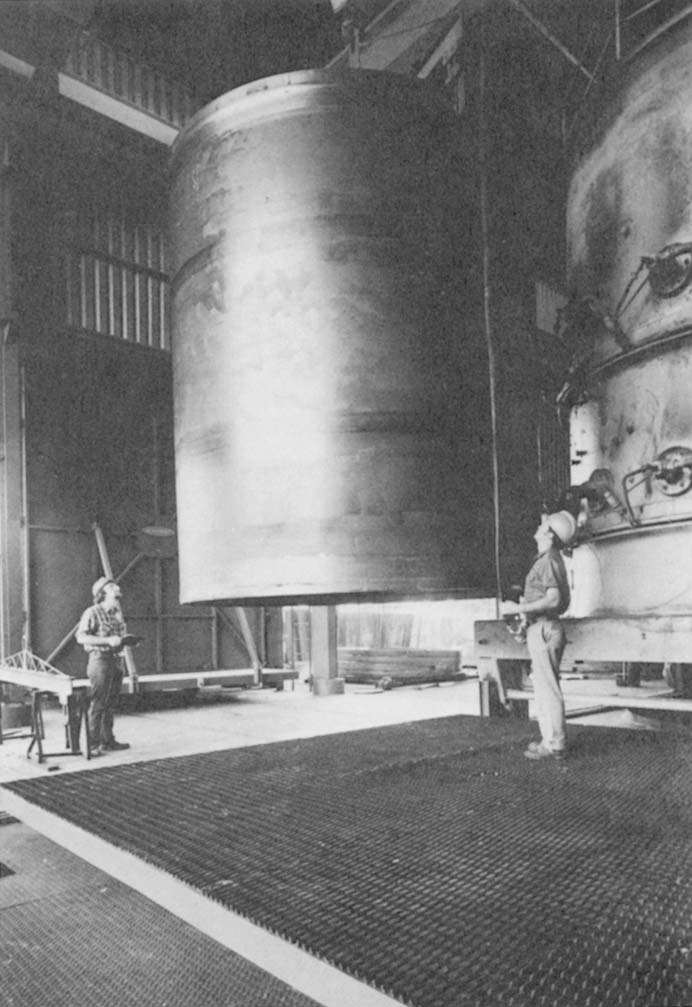

Hatsopoulos never found a material that would permit the thermionic conversion to take place efficiently (he’s still looking) but along the way the fledgling firm assembled a capable engineering and scientific staff that was soon developing specialized knowledge of a variety of related fields. They became experienced in working with alloys of various metals, which led to a new business in the heat treating of metals for other companies. Likewise, engineers became experts in the mechanics of how heat transfer and energy efficiency might be improved. Natural gas utilities–worried that electric utilities were luring large industrial customers away from gas-fired furnaces–financed Thermo Electron to design more efficient gas-fired furnaces. The company subsequently started to make furnaces.

And so it has been repeatedly: some of Thermo Electron’s greatest commercial successes have been almost accidental. One development led to another–not necessarily anticipated or even desired at the start. Hatsopoulos recalls one particularly revealing incident involving the firm’s work on a contract for Ford Motor Co. for a low-polluting, energy-efficient engine. Ford was unable to get instrumentation to detect the low levels of exhaust pollutants needed to comply with new government standards. Thermo Electron’s laboratory developed an experimental instrument capable of measuring low levels of the pollutant, but Ford officials rejected Hatsopoulos’ offer to produce the sensitive instruments for them, saying “You’re not in the instrument business, you’re out of your minds.” One week later they called back and placed an order for 10 instruments, payable only if the company delivered.

Hatsopoulos recalls that:

We went into a crash effort for three months–to set up production, to test reliability. We had no space. They took my office. It was really something. And we made the delivery–we kept our fingers crossed that it would work, and it did. What happened afterwards was really unbelievable. I wish it would happen again one day. We had no distribution system, no marketing. Within days, we got a call from General Motors, who said ‘We want 100 instruments, because Ford told us you’re the only supplier in the world.’ And for the next six months, there were calls from Toyota, BMW, Mercedes. And that business–including all the R&D and startup costs–we still netted $500,000 in profits that first year. We stayed being a monopoly for two years. By that time, (other suppliers) brought in instruments. But by that time, we were so solidly entrenched that even 10 years afterwards, we have 50 percent of the world market.

The episode reeks of romance: a genuine business adventure. And from the romance issued forth an entirely new line of business for Thermo Electron. But as the company grew, so did its need for management controls, order and discipline. The company had multiple lines of business, and increasing variety of customers and markets, a growing number of manufacturing plants and sales organizations. It also had to allocate a rising stream of funds for investment and R&D across a widening spectrum of activities. All this had to be coordinated. Hatsopoulos, who had once intimately involved himself in the firm’s research activities, could no longer afford to do so. Most other top executives had to distance themselves increasingly from the firm’s day to day operations and attend to what has progressively become, in the postwar period, the primary preoccupation of large firms’ senior management: determining their companies’ future direction and setting broad policies for R&D, product development, investment and personnel–policies that are then executed by middle level managers.

What has resulted in a new set of ideas and techniques on how executives can best run their firms. These new ideas reinforce the notion of the “professional” manager: someone who can understand and run almost any business. For the essence of the new management theory is that virtually all businesses can be understood in terms of universal principles. The Strategic Planning Institute, one of the principal centers of the new management theology, puts it this way: “All business situations are basically alike in obeying the same ‘laws’ of the marketplace.”

Strategic Planning

One widely accepted law is the “experience curve.” In simplest terms, it postulates that every doubling of production results in a drop of 20 to 30 percent in unit costs. Another common belief (in the words of the SPT) is that “product characteristics don’t matter….It doesn’t matter if the product is chemical or electrical, edible or toxic, large or small, purple or yellow.”

What matters for profits–in this view–are other indicators that apply to all types of businesses: market share, investment intensity, market growth, and productivity. To some extent, all these ideas came to be understood as “strategic planning.”

Even a short visit to Thermo Electron disabuses the idea that management is an entirely rote or totally analytic process, no matter how formalized the planning and reporting systems. Ultimately, individual judgments, prejudices and personalities count heavily. Robert C. Howard, Thermo Electron’s senior vice president, argues that one of the greatest of executive virtues is the ability to “calibrate people”: the instinct to decide who can and can’t be believed–and how much.

John Appleton, vice president for research, reports that much of the R&D is located in separate research units in the firm’s individual businesses. Part of the motive is the NIH, or “Not Invented Here” syndrome. Suggestions or solutions originated at headquarters tend to encounter resistance. Peter Pantazelos, executive vice president, regularly visits some of the firm’s more than 20 plants and offices. He believes it’s important for local managers to see someone from headquarters–to know they’re not alone.

As the company expanded, Hatsopoulos and others also began to feel the need for more formal skills. Recalls Howard:

Around the middle of the 1970s we began to develop as managers. Almost all the key people here came out of engineering. We never had any formal business training. We had to learn on the job…George ten years ago would be totally unqualified. So would I and so would Peter (Pantazelos). The people part of management, we were always pretty good at. But we started to look at markets–what we should drop, how to manage investment…Our ability to analyze new ventures or prospective acquisitions is infinitely better today. (We know better how to evaluate) how they stand next to the competition. We didn’t even know how to make those investigations.

What emerges at a company like Thermo Electron is a constant tension between the firm’s system for corporate control and the desire to maintain the looseness that nurtured its technological opportunism. Controls are formal. Business managers are evaluated, in part. on the basis of RONA–return on the net assets of their division, or profits. The company’s financial controls generally favor business divisions that produce cash–which means generating more funds than needed either for operating costs or new investment. This inevitably puts a check on risk-taking. And some executives believe that the company’s growth has, in fact, been too haphazard. They want more planning and better prediction.

Others are skeptical. Senior vice president Howard is one. He argues that the commercialization of useful R&D requires a rare sequence of events and someone–an “entrepreneur”–to make them happen. The sequence of events includes successful R&D, the creation of a useful product, the understanding of customer needs, and the development of manufacturing, sales and distribution systems. “A good solid entrepreneur with judgment is rare,” he says. “We don’t have a lot of these guys. When we find one, we nurture him.”

Most corporations grapple with this tension. Corporate performance is absolutely critical to the nation’s economic health, for it controls most of the country’s economic base and directs much of its R&D. But the great contradiction of the corporation is that the more it succeeds, the more it threatens its own future. The bigger and more diversified it becomes, the more it faces potential internal inefficiencies. Oliver Williamson of the University of Pennsylvania argues, for example, that economies of scale in manufacturing, marketing and research can easily be offset by diseconomies in communications, coordination, and decision-making.

Major corporations often also experience frustration in achieving major technological or product breakthroughs. Ralph Biggadike of the University of Virginia found that large corporations have a difficult time starting new lines of business independently. On average, he found that it takes between 7 and 8 years for them to reach a break even point.

Companies started from scratch don’t do much better. It was more than a decade before Thermo Electron was sufficiently established to issue stock to the public. Venture capital firms (which invest in new companies) report essentially the same experience: only rarely do firms become instant successes. Consequently, most venture capital funds have a commitment period of up to a decade. During that time, investors can’t withdraw their funds.

But this long gestation period and great riskiness clash with the corporation’s desire for assured growth in earnings. It also collides, according to the University of Virginia study, with internal standards for judging executives’ performance. Robert Hayes and William Abernathy, writing in the Harvard Business Review, argued that the effort to put corporate performance and goals into a rigid analytical framework often obscures and suffocates the basic sources of innovation and growth. “…Maximum short-term financial returns have become the overriding criteria for many firms,” they wrote.

Spinoffs and imitations of existing products are favored as a result of excessive preoccupation with market share analysis. Demand for these products–and presumably their market shares and profits–can be more easily predicted than for genuinely new products, where demand and potential profits might be either enormous or nonexistent.

One paradox of the modern corporation is that it is both a highly personal and impersonal creature. Most big firms are sufficiently large and diverse that senior executives have little influence over day-to-day or even year-to-year performance. In this sense, they are powerless. But the firm’s ultimate character and direction can very much reflect the ambition and vision of a few people at the top. For major decisions, they retain enormous authority.

This conditions the nature of risk-taking. In some respects, the larger the firm, the greater the difficulty. For Thermo Electron, a new business with a potential of $20 to $25 million in sales after five years would be significant–about 10 percent of the size of the current company. But for a firm with $2 billion in sales–which covers about the top 200 companies in Fortune’s 500 industrials–that new business would have a negligible effect on the company’s results.

The frustration of senior management in many large firms is that, separated from day-to-day operating decisions, the only way they can dramatically influence their firm is to make a major acquisition. In theory, mergers might represent a potent force for enhanced economic efficiency, and they often do. Firms with superior technology can purchase companies with ongoing manufacturing, sales and servicing organizations. Adapting the improved technology to existing products then results in a significant jump in sales (this happened several times in Thermo Electron’s case). Poorly managed firms can be taken over by better managed companies. Firms with superior technology–but with inadequate financing or inferior sales or distribution resources–can be acquired by firms with marketing experience and large cash reserves.

But none of this is preordained, and observers of the merger boom of the late 1970s wonder increasingly about the benefits. Most economic studies have failed to find any overall clear-cut advantage in recent mergers. At best, the effect seems to be neutral, implying that some mergers are favorable and others are not. Close students of mergers have concluded that motivations are often highly personal: excitement, ego-building. “The more recent mega mergers aren’t based on an economic justification that the combined companies will produce earnings growth faster than either of them individually,” says Samuel Ostrow, a New York public relations consultant who has advised companies involved in major acquisitions. “Something else is going on. It’s ego.” Privately, many economists and investment bankers agree.

To raise these possibilities is to recognize how the evolution of the modern corporation has changed the nature of the economy’s performance. In an economy of perfect competition–the textbook idea–the firms are small and atomistic. If they don’t make what society wants, or don’t make it efficiently, they go out of business. But the large corporation has staying power, and this alters its character. Its established businesses generate substantial profits and shelter a considerable stock of assets against which it can borrow.

This stamina represents both its greatest potential virtue and greatest potential vice. It can afford to take the longer view: that is, it can devote the time and money necessary to nurture new and costly ventures. But it can equally be a source of huge waste: that is, it can embark on a series of misguided ventures. Ultimately, it may suffer the fate of the small inefficient firm–bankruptcy. But, meanwhile, it can squander the financial, human and physical capital associated with its mistakes. The main question about postwar managerial capitalism is which of these tendencies predominates. That there is no clear-cut answer is the essence of the dilemma of the mature business system.

©1983 Robert J. Samuelson

Robert J. Samuelson, economics reporter for the National Journal, is investigating changes in the U.S. economy since World War II.