TALLAHASSEE AND SOUTH FLORIDA–Speaking softly, but with an occasional “damn,” the lieutenant governor of Florida, Democrat Buddy McKay, said last spring in his office in the Florida State Capitol that he believed a seat in the U.S. Senate was stolen from him six years ago.

“I felt that way very strongly at the time,” he said. “I felt that we had legitimately won and it had been stolen. I’ve gotten to a point now where I’m not gonna go through my life lookin’ back. That’s somethin’ that has happened and I’m movin’ on.”

Without pointing his finger at anyone, MacKay alluded to a “problem in the software” which counted the votes in computers in that election as “a separate area of suspicion”; to a ballot layout in the four biggest counties that were regarded as favorable to him which he thought caused voters not to see the Senate race; and to an unprecedented “dropoff” of the computer-counted votes in those four counties. That dropoff alone may well have defeated MacKay.

“You can understand why MacKay would feel badly,” says Mitch Bainwol, who was the campaign manager for MacKay’s opponent, Republican Connie Mack, in 1988. “But that it was stolen from his is silly.”

The puzzle of the 1988 general election in Florida has alarmed and baffled election experts ever since and bears dramatically on the general question at hand, whether the counting of votes in computers, which is where most Americans’ votes are now counted, is or can be sufficiently reliable and secure against fraud. The amiable MacKay’s observations, proffered from his present position as Florida’s number two official, may retrieve from recent political archives a wormbox of questions which have not yet been officially investigated.

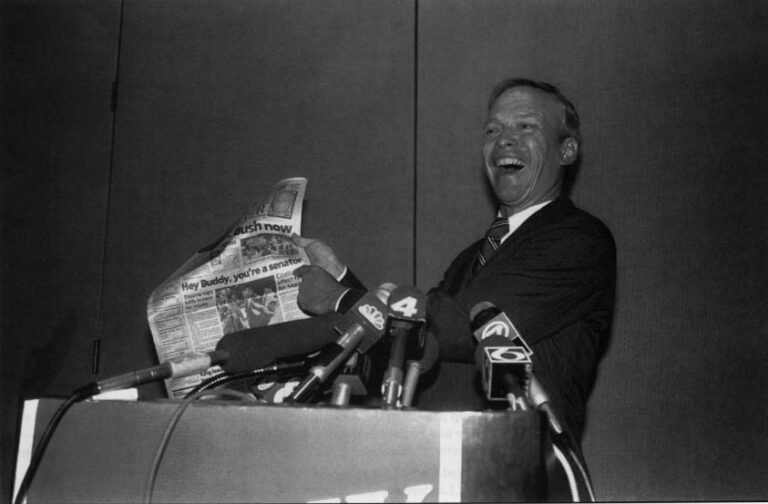

Immediately after the returns showed MacKay’s defeat by 35,000 votes out of more than four million cast in November 1988, he said there had been “irregularities” and “oddities,” and he called for a manual recount in five counties and asked to be permitted to examine the votecounting computer software. Later he said that his campaign’s late polls had showed him with a 5% to 9% lead.

Supervisors of elections in all of the five counties refused to hand over their software for examination on grounds that it was the secret property of the election-equipment companies which had sold it to them. (“A damned outrage,” MacKay called that during my recent interview with him.) An attorney for MacKay’s opponent, Connie Mack, blasted MacKay for questioning the outcome and asking for recounts “without a single shred of evidence.” Only one of the counties granted MacKay a manual recount, and that resulted in only trivial changes in the figures. Discouraged and worried that he would be branded a sore loser, MacKay abandoned his challenge and Mack became Senator Mack.

What did MacKay mean by “irregularities” and “oddities”?

His four strongest big counties were Dade (Miami), Broward (Fort Lauderdale), and Palm Beach, a tier of three urban counties alongside the Atlantic Ocean, and Hillsborough, which surrounds Tampa Bay on the Gulf of Mexico. Usually from one to three or four percent of the people who vote in a presidential race do not then vote in a U.S. Senate contest which is on the same ballot. This and similar phenomena are known as “the dropoff.” In a comparable presidential-year U.S. Senate election in these four counties in Florida in 1980, for example, out of every 100 Floridians who voted on the presidency three did not vote for a Senate candidate.

But in 1988 in the same four counties fourteen out of every 100 citizens who voted for President were not recorded as voting for either MacKay or Mack.

Comparing 1980 to 1988, in Broward County the Senate-race dropoff increased from 3.6% to 6.8%; in Dade County, from 4.2% to 13.1%; in Palm Beach County, from 1.1% to 16.5%; and across the Panhandle in Hillsborough, from a flat 1% in 1980 to a whopping 24.5% in 1988.

Thus in Democratic Hillsborough County one in four voters for President disappeared from the voting totals for senator.

The vertiginous dropoff ended at the county line. In the same election in the neighboring county of Pinellas (most of which is a peninsula between the Gulf and Tampa Bay), the dropoff was less than 1%–one-twenty-seventh the rate around the bay. Pinellas is a Republican county.

Likewise, in the entire state excluding the four big MacKay counties fewer than one out of every hundred voters for President, a total of 25,000 out of 2.8 million, were recorded as not having also voted in the Senate race. In MacKay’s big four counties 210,000 voters disappeared from the Senate race after having voted for President. He had carried the four anyway by margins totaling 121,000 votes, but if his 55.5% margin of victory in them had held among the voters who disappeared (except for the statewide 0.9% falloff), his margin of defeat would have dropped to about 12,000, three-tenths of 1%, which would have required a mandatory statewide recount under state law at that time.

Mitch Bainwol, Connie Mack’s 1988 campaign manager who is now his top staffer in Washington, contended on the senator’s behalf that the large drop-off did not change the outcome. He realized, he said, that some people argued that it did, but the Mack camp, he said, argues the contrary.

Evidently the dropoff within the big four counties was concentrated in Democratic precincts, judging from an investigation of Dade County precinct returns by the Miami News, which established that the Senate dropoff there was more than twice as likely to occur in the heavily Democratic areas where blacks and retirees lived than in Republican suburban areas. If that was true, by itself the big-four dropoff could well have defeated MacKay.

In MacKay’s big four counties the dropoff defied common sense, but the “jump-ups” down-ballot in the next two much less important races mocked it. Taking as 100% the total vote for President in the urban hotspots of South Florida–the body politic of those four counties at the polls on November 8, 1988–that body, after shrinking to 86% in the Senate race, then swelled back up to 97% in the voting for Secretary of State and 98% for Treasurer/Insurance Commissioner.

In the same four counties that day more people voted on eight of the eleven mostly minor proposed amendments to the Florida constitution than voted in the Senate race. These eight jump-ups, depending on the amendment, were as large as 14%: on amendment ten, to limit non-economic damages in civil actions, 1,413,352 citizens were recorded as voting, compared to 1,299,165 who had been recorded vas voting for MacKay or Mack.

“We have never found out why that happened,” Charles Whitehead, the chairman of the Florida Democratic Party in 1988 (who is the Ford dealer in Panama City, Florida), said to me in April. “The only race that falloff happened in was the Senate race.”

When the undeniable anomalies were reviewed in the figures for county after county and precinct after precinct, they appeared to reflect a long chain of contradictory and unbelievable events. “Something’s screwy with those numbers,” MacKay’s campaign manager, Greg Farmer, said at the time. He could not believe, for example, that in Democratic Palm Beach County, Florida’s MacKay, who won 49.6% of the state vote, had trailed the Democratic candidate for President, Michael Dukakis, who had received only 39% of the state vote. MacKay lost the state by 35,000 votes; Dukakis lost it by 960,000. “C’mon, now,” Farmer said.

Yet Palm Beach was the one county whose elections chief, Democrat Jackie Winchester, had granted MacKay a hand recount in selected precincts.

The director of elections in Florida, Dorothy Joyce, emphasized to me, concerning the 1988 Senate election: “We didn’t conduct an investigation.” Neither did any of the big four counties. What might explain the mysterious falloff in the Democrats’ best counties?

“I wish I knew, I wish I knew,” the chief of elections in Dade, David Leahy, said in his office in Miami last year.

When voting on the Computer Election Systems (CES) “Votomatic” system which was used in three of the four big counties in 1988, a voter must jab a stylus through three aligned objects:

through holes beside the names of their chosen candidates in a multipage booklet which lists all the candidates and propositions, through a perforated thin metal template which is positioned underneath the booklet, and then through tiny rectangles (each possible vote having been assigned to one of them) on a card under the template (a computer-countable card which is, in fact, the official ballot). Some computer experts suggested to David Beiler, the editor of the magazine Campaigns & Elections, that pages in the booklets could have been misaligned with the underlying ballots, causing mis-votes, or that the templates could have been constructed so as to block the recording of certain votes.

The most disconcerting suspect, a threat to the security of votecounting in every computerized system, was the computer experts’ programming which controls the votecounting. “I think somebody made a mistake in programming,” Robert Naegele of California, the most widely-employed specialist in computerized votecounting in the U.S., ventured to a Los Angeles Times reporter, William Trombley. Bad programming of a vote count can be either a mistake or intentional manipulation to achieve a desired result.

The leading authority on counting votes in computers is Roy Saltman, the computer expert at the National Institute of Standards and Technology whose two copious federal reports are accepted as bedrock in the field. “These strange results,” he muttered to me in 1989. “Nobody seems to understand them.” The cautious scientist wrote in 1991 that “the questions raised in that senatorial contest about possible computer-program errors will never be answered with any confidence, and may color Florida voters’ perceptions about the integrity of computerized voting for the foreseeable future.” Late in April Saltman said to me: “I thought it was extremely suspicious that the large counties where the Democrats were supposed to be strong were the very ones where this enormous drop-off occurred. It leaves a very, very bad taste in one’s mouth.”

According to Mitch Bainwol, Mack’s chief staffer, there were three reasons for the drop-off: “There certainly is a drop-off in every election. That’s point one. Second, the names were so close, Mack, MacKay…There was a lot of confusion between `Connie’ and `Buddy.’ Third, the placement of the race on the ballot.”

Votecounting is controlled in computers by “source code,” the electronic computer language that orders the computer (which is no adding machine) how to count and what to do. In the “Votomatic” systems in the big counties in 1988 the source codes had been programmed by their corporate provider, Business Records Corporation (BRC) of Dallas, on whose computerized systems at least 40 million votes are counted during the biggest U.S. election cycles.(1) As challenges to the 1988 Senate outcome flared in Florida, BRC (which was then called Cronus Industries) did not respond from its redoubt in Texas to urgent calls from the press and the MacKay camp. A week after the election Perry Esping, the CEO of Cronus/BRC, did tell Frank Ruiz, a business reporter for the Tampa Tribune, that his company had to stay out of the controversy and added: “It has all worked well. How we do it is our business and the counties’.”

The worst possibilities, however, were made clear enough during a series of lawsuits brought against CES, the corporate predecessor of Cronus/BRC, alleging election fraud during elections in Elkhart County, Indiana, in the 1980’s. The final suit in the series resulted in a $40,000 settlement for the plaintiffs, but, perhaps more importantly, produced in July 1988 the sworn testimony of Jerry Williams, a programmer for CES that a “subroutine,” identified by the letters “CRT-RTN,” was embedded in the “EL-80” votecounting source code which was in use in Hillsborough and Pinellas counties, Florida (as well as other places Williams said he “could not think of just now”). Hillsborough County election officials had used it, he said, for a subroutine which enabled the display of cumulative results on remote video terminals, but he conceded that “CRT-RTN” could become any kind of computer code that a programmer wanted to turn it into.

All a programmer had to do, Williams said, was key his chosen subroutine into the source code at the line for “CRT-RTN” and blank out an asterisk which stood at the leftmost edge of the line, and “at that point in the program, it will be executed.” The CES programmer’s testimony, developed under close questioning by the attorney for the plaintiffs, David Stutsman of Elkhart, established in substance that the CRT-RTN subroutine could be used for any purpose, including the secreting of “Trojan Horse” computer code that could change an election outcome.(2)

There is no evidence that any such asterisked subroutine used in Florida had any but routine purposes. Chuck Smith, the operations manager of Hillsborough County’s election department in 1988 and now, told me last year in Tampa that he was not familiar with the subroutine Williams had identified, but added: “There were several subroutines, because at that time we had the source code.” One of them, he said, was used to control the counting of absentee votes, and “we had another routine that was put in.”

The way the ballots were laid out in the voters’ booklets was also identified as one of the possible causes of the dropoff in the four counties. Last spring MacKay emphasized this explanation and seemed angry that no one on his side had known of the danger. Connie Mack’s spokesman, Mark Mills, said in the wake of the election that ballot layout (in the big four counties) may have caused people not to vote in the Senate race. “But who is to know?” Mills added. Dorothy Joyce, the Florida elections chief, said in an interview last year: “We thought all along it was purely the ballot layout that was the problem. I still believe that’s what it was…It was just very obvious.”

Both the presidential and senatorial contests had been presented to the voters on the first page of multi-page booklets in all of the four key counties, with the Senate race occupying the lesser space at the bottom of the page. Just such a layout had been blamed for a rare 13% dropoff in a Senate race in California in 1976, in spite of representations that the same layout had failed to cause such effects in the same election elsewhere in that state and on other occasions around the country.

All the election officials of the big four counties whom I interviewed in Florida disclaimed having had prior knowledge of the 1976 case in California (it had been reported prominently in 1976 in Election Administration Reports, a newsletter which many professional election people read). On the other hand, several of the Florida officials revealed or confirmed that in Florida members of a multi-county, technically-oriented “CES Users’ Group” met in advance of the 1988 election to discuss such questions as ballot layout and that similar users’ groups continue to meet in South Florida. (3)The Dade County elections chief, David Leahy, volunteered the information that the supervisor of elections in Broward County, Jane Carroll, had theorized the 1988 dropoff might be explained by unwillingness among liberal Democratic Jewish voters, many of whom live in condominiums up and down the Atlantic coast in Dade and Broward counties, to vote for the centrist MacKay.

When I asked Carroll about this in her office in Fort Lauderdale, she substantially confirmed it as her view. The self-confident, loquacious Carroll, who is a Republican, added for good measure that voters in her county were disenchanted with MacKay because of a too-recent bitter primary campaign. “The reaction from everybody was, `How could this have happened?'” she said. “Well, I think it happened because people voted for Mack.”

Carroll said that right after the November 1988 election she saw and heard MacKay on TV, standing on his porch and saying: “`There were irregularities,'” and she continued: “To me that was an irresponsible statement, even though he is a nice guy…For you to jump up and say there were irregularities you oughta know there were, because we’ve got enough people turned off on voting anyway, and we don’t really want to discourage people by sayin’ that.”

The elections chief in Hillsborough County in 1988, Robin C. Krivanek, had said that, contrary to Jane Carroll’s guess about what voters were thinking, those who had voted for George Bush for President had made a conscious choice not to vote for Connie Mack (who was being characterized as substantially to the right of Bush) for the Senate. Still, Krivanek was shaken. She wrote her own canvassing board (urging a recount which the board denied) that “this is one of those instances in which it is not sufficient to say `trust us.'”

Early in 1989 a legislative committee held hearings focused on the strange results which had put Connie Mack in the Senate. Dorothy Joyce, the state elections director, made a frightening admission to the committee. “Right now, we don’t really have any way to check that votes are being counted properly,” she said. “Right now there is no way to assure that every vote is being counted.” Robin Krivanek wrote the committee chairman after the hearings: “We still are just as convinced as before of the integrity of our system, but that certainly does nothing to explain the vote. I sensed that same lingering doubt in your mind…” A few months later Joyce was quoted: “With the big scare we had last year, the electorate doesn’t know whether their vote counts or not.”

Later in 1989 the Florida legislature passed a new statute intended to reform computerized elections, but has failed to appropriate the $669,000 which its budget staff had deemed necessary to enforce it. The division of elections has received “not one dollar,” Joyce said in the course of a series of interviews.

Even so, Florida is now said to have the toughest standards in the country for the certification of computerized voting equipment, and Judith List, the well-qualified chief of the certification program, is highly regarded across the country. Dorothy Joyce says, “I feel 1,000% better because Judith and her folks are doing everything they can” to assure good votecounting.

Yet Judith List told me as we walked across the state Capitol grounds in 1993 that tampering with the votecounting software cannot be excluded, saying: “If a trusted assistant in an election supervisor’s office wants to do something, well of course: he can. We know that.”

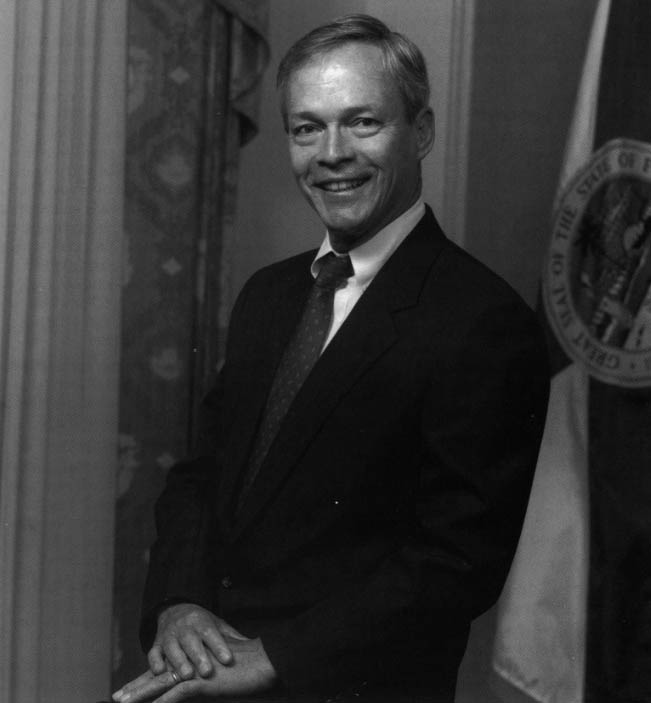

Buddy MacKay’s face forms a thin triangle topped off neatly by his close-cut graying hair. He is a rather slight person physically. Compared to most politicians his friendliness is on the quieter side.

Reliving the agonized few days in November 1988 when he had to decide whether to press his initial challenge to the outcome, the lieutenant governor said, “I couldn’t get access to the inner workings of the programming…I could not get into the computer program at all, period.”

(Senator Mack’s administrative assistant, Mitch Bainwol, snaps, “I don’t know what he’s talking about,” on that point. Bainwol insisted to me, on the basis of his recollection, that the software in the challenged counties had been given “a very rigorous test.”)

Only after the election did MacKay realize there might have been a problem with the ballot layout (his campaign people had not even looked at the layouts beforehand, so he could hardly object to them afterward). State election-fraud laws were still keyed to the switching of ballot boxes, not to “the inner workings of a damn computer,” he said, and his legal advisers told him that his best recourse was a federal civil rights suit.

“Frankly,” he said, “I was so exhausted and so dispirited I told them `Look, if that’s what it takes, I don’t have the spirit left to do it.'”

“My understanding is that it’s possible to program a computer for it to count wrong for a while and then straighten itself out,” MacKay commented. “Now that I realize the level of sophistication, I realize how easy it would be for somebody to in effect rewire that program for a brief period of time and then have it straighten itself out. I don’t know how anybody could prove that.”

Rising as the interview ended, Lt. Gov. Buddy MacKay said “I just hope it doesn’t happen to somebody else.”

Notes

- For each election, additional software also has to be “initialized” to match the source code to the specific characteristics of each election. This is usually done by local election computer workers. Local supervisors of elections sometimes, however, hire outside computer consultants to do the initializing for a jurisdiction. In either event, the identities of the local programmers are known.

- An excerpt from the transcript of testimony given by Jerry Williams during a deposition taken on July 14, 1988:

- STUTSMAN: And where is this subroutine that’s called up?

- WILLIAMS: It doesn’t exist. If you want to use that, you’ve got to write your own routine…

- STUTSMAN: If [the programmer] is a COBOL programmer, they could write whatever subroutine they preferred to write to–

- WILLIAMS: This will go call the routine that’s named CRT routine.

- STUTSMAN: As long as the programmer calls his subroutine that [`CRT-RTN’], whatever it may be–

- WILLIAMS: As that point in the program, it will get executed.

- STUTSMAN: And the program may do anything, a subroutine will do whatever the programmer says as long as he calls it that?

- WILLIAMS: Yes.

- In 1992 Florida’s Broward County again presented voters with the questioned layout (no steps have been taken in Florida to discontinue its use). Although Ross Perot’s candidacy had heated up the presidential race and the 1992 Senate race in Florida was a 3-1 walkaway for the winner, the 16.2% dropoff in the Senate race in Broward even under those circumstances hardly put the ballot-layout theory of the `88 dropoff out of its misery.

@1994 Ronnie Dugger

Ronnie Dugger is the publisher of The Texas Observer and is investigating computer vote-counting during his Alicia Patterson year.