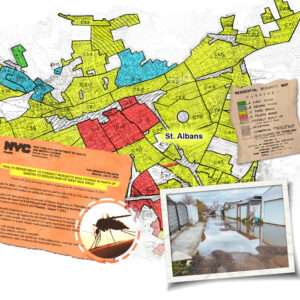

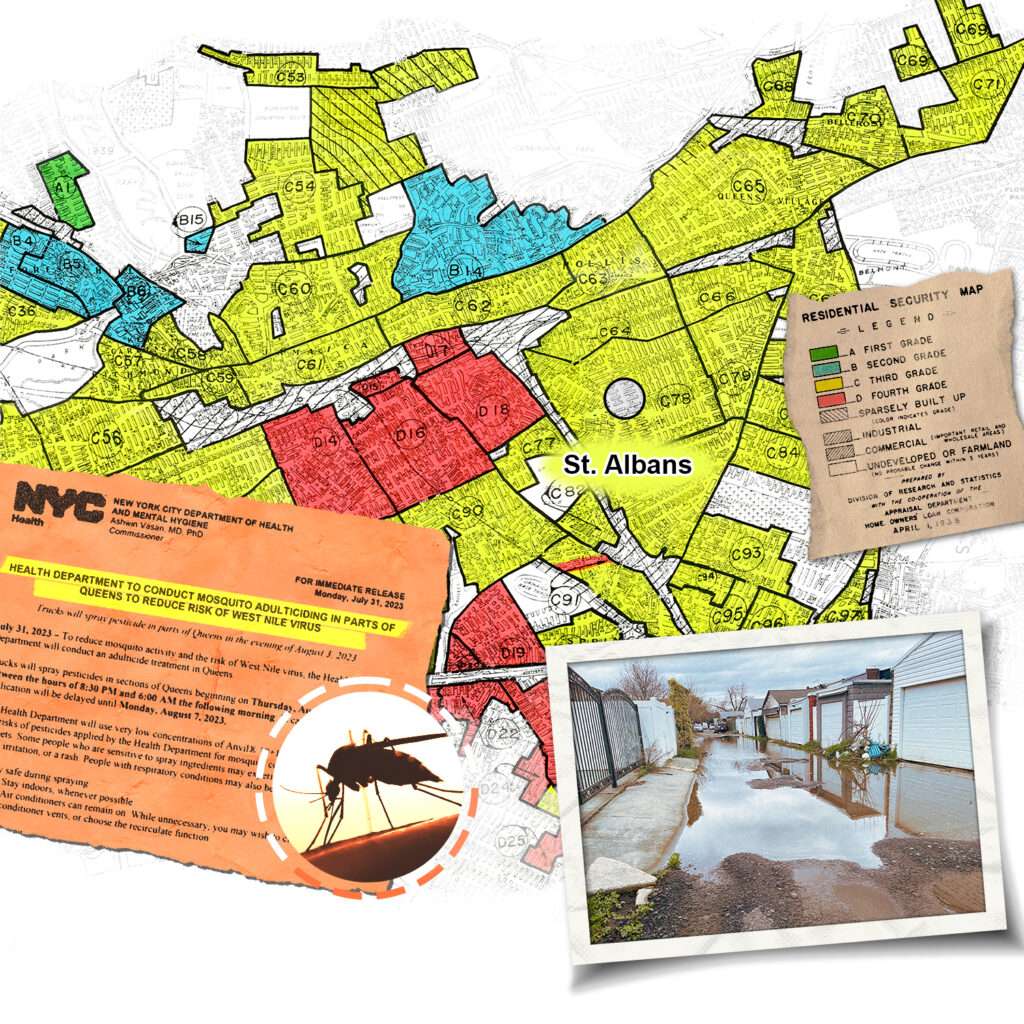

Decades before Elizabeth Blaney, now 84, moved to St. Albans, the neighborhood was shaded yellow on maps made by the federal government. The color yellow could mean there was a high number of immigrants—or that there was a possibility of Black people moving into the neighborhood.

But being coded yellow also meant environmental threats existed. In St. Albans in the 1930s and ’40s, that meant being in low-lying land or having few to no sewers or poor transportation options.

Blaney moved to St. Albans about three decades after those maps, made by a government agency called the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, were created. She didn’t have a car in the suburban neighborhood, but she was able to walk her children to the nearby elementary school. She could also walk to the grocery store and church, and she formed relationships with neighbors she’s still friends with today.

However, the aspects of the neighborhood that were first deemed detrimental by those federal maps—long before Blaney arrived—still persist. Today, St. Albans still sits in low-lying land. There are still sewer problems and these infrastructure problems are exacerbated by flooding and the even-more-intense rain that is expected to fall on the city now and in the coming years. Residents have long been vocal at their community board meetings about the issues that affect St. Albans. And now there’s another one that residents may have to add to the list: mosquitoes.

Blaney has heeded advice from the city when it comes to protecting herself from mosquito-borne disease. To prevent standing water, which attracts mosquitoes, she pours out any containers and flower pots that catch water when it rains. She lights candles to keep insects away. She uses sprays to protect herself.

But Blaney and her neighbors say they can’t do much once heavy rains, or even not-so-heavy rains, fall from the sky and leave gray water that ultimately lands in their rocky and cratered alleyways, which turns soil spongy. Neighbors say the rainfall creates “ponding” that sometimes sits there for days.

Ponding can breed mosquitoes—a vector that carries diseases such as the West Nile virus. In New York City, mosquito season lasts from about April to October, but the hotter summers and warmer springs and falls due to climate change can encourage mosquitoes to breed for longer periods of time and lead to a rise in other infectious diseases.

“I think the climate issue is a factor here when it comes to the kind of weather we’re seeing, and the kinds of rainfalls we’re seeing as well,” said Blaney. “I think it’s more of it than we usually see.”

Blaney is banding together with neighbors to come up with a fix to ponding. On the five blocks her block association is targeting, she estimates that about 300 homes are affected. New York City residents are urged to report chronic standing water to 311, but the terms etched into the deeds of some St. Albans residents—documents written decades ago that didn’t have in mind the changing climate caused by humans—state that property owners are responsible for maintaining their sections of the alleyways.

The city health department says it’s up to homeowners to remove standing water from their properties, but with more frequent and intense rain, hotter summers, and milder winters due to climate change, a private property matter such as standing water in an alleyway can become a public health hazard.

Neighborhoods of color are on the frontlines of the effects of climate change and environmental hazards, including flooding, extreme heat, and poor air quality. Black neighborhoods such as St. Albans and other parts of southeast Queens, as well as sections of central Brooklyn, upper Manhattan, and the Bronx get hotter than other parts of the city.

The city is no stranger to catastrophic weather disasters that have cost lives. Superstorm Sandy in 2012 killed more than 40 people. When Hurricane Ida hit the city nearly a decade later, more than a dozen people died—mostly residents of color. The city has plans in place to protect residents, but the creeping everyday effects of environmental hazards and climate, such as sewer backups, heat waves, heavy rain, and drought, also cause insurmountable harm. Large-scale solutions, such as surge walls, can cost billions of dollars and years to get done. Meanwhile, Blaney and her neighbors are hoping to raise $300,000 to repave their alleyway as soon as they can.

The impact of redlining

Blaney moved to her brick St. Albans rowhouse one year before the federal government outlawed redlined maps under the 1968 Fair Housing Act. Before then, maps color-coded homes that make up her neighborhood as “declining.” Along with describing detrimental factors such as the neighborhood sitting on low land, being high in foreclosures, having the railroad nearby and poor transportation services, redlining documents explicitly said that St. Albans was at risk of “negro encroachment north of the borough.”

The legacy of redlining, which began nearly a century ago, still affects health outcomes today, including those related to the warming planet. According to the city’s recently released study on environmental justice, two-thirds of New Yorkers who live neighborhoods that were historically redlined are classified by the city as “environmental justice” areas today. Redlined neighborhoods have an increased risk of flooding.

Because of redlining, inequitable zoning policies, and the disinvestment that followed, neighborhoods became further segregated and ended up with perpetual sewer backups, fewer parks, and many abandoned homes. Even before the federal government drew these maps, Black residents in southeast Queens voiced concerns about receiving inferior services compared to the northern part of the borough. Surrounding neighborhoods such as South Jamaica, which today ranks among the top neighborhoods with the highest complaints of confirmed sewer backups, formed a group as far back as 1926 and complained at one of its first community meetings about the failing sewage system and rundown roads.

The area where Blaney now lives was shaded not red on redlining maps but yellow, which indicated the neighborhood was “definitely declining.” Queens was less redlined compared to other boroughs but racist practices in the 1960s and ’70s, including racial covenants and blockbusting, scared many white residents and caused them to leave the area.

Today, anyone strolling down some of the blocks between Francis Lewis and Farmers Boulevard in St. Albans can see that the streets are lined with homes with stained glass windows and porches lined with colorful buckets of bright daffodils. But even though the majority Black neighborhood has a median income close to $100,000 and a high percentage of homeowners compared to the rest of the city, this socio-economic status may not protect them from adverse health effects from the environment.

In New York City, Black neighborhoods are more at risk for extreme heat. St. Albans is one of the neighborhoods that ranks the highest on the city’s heat vulnerability index, a tool that measures adverse health risks, including death. Lack of trees, and other factors such as high surface temperatures, can lead to the urban heat island effect that traps heat in neighborhoods, making them feel even hotter.

In the summertime, Blaney and her neighbors want nothing more than to enjoy an evening in their backyards, but with or without ponding, mosquitoes get in the way.

“We feel them biting us,” said Blaney. ‘We can’t even sit outside.”

Crows falling from the sky: West Nile virus makes a home in the world’s borough

The West Nile Virus was first detected in North America in Flushing, less than 10 miles from where Blaney lives, in 1999. “There were these…large die-offs of crows happening around the city,” Denis Nash, an epidemiologist at the CUNY School of Public Health, recalled in an interview. Back then, he was part of a training program with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to learn how to investigate disease outbreaks.

The virus can spread between infected birds and mosquitoes. Humans who contract West Nile Virus mostly get it by being bitten by a mosquito. There are about 50 types of the blood-sucking arthropods in New York City, but the virus is primarily transmitted through the Culex species.

Back then, Nash wasn’t prepared for the disease and neither was the city. “By the time this outbreak started in 1999,” he said, “there was no one at the health department that I could go to, or that we could go to, for help.”

Since landing in New York, the virus has spread throughout the continental United States. There have been more than 50,000 cases and nearly 3,000 people have died across the country, although dying from the disease is rare and only about 1 out of 150 people get seriously ill, according to the CDC. Those who do become ill may experience muscle weakness, tremors, or paralysis, or fall into a coma. Mild to moderate symptoms include a fever, headache, vomiting, or a rash. People who are 50 years or older are the most likely to get ill.

Because of the number of elders in St. Albans and surrounding neighborhoods, residents have long called for more health facilities, including a 24-hour hospital. In Blaney’s ZIP code, about 40 percent of residents are over the age of 50, according to U.S. Census data. There are currently no vaccines for the virus, although the CDC wants to move toward deploying one. The agency also acknowledges that current measures to control the virus are not enough to reduce cases.

While most people who get infected are asymptomatic, New Yorkers are still affected by the virus. Since 1999, there have been more than 13,000 undiagnosed cases of West Nile fever in New York City, according to the health department, and that might be an underestimate.

Mosquitoes start their life cycles in water. Some lay their eggs in standing water, which provides nutrients to their babies to grow before they grow up and buzz off into the sunset to live their lives on land. Warmer temperatures can make a cozy breeding ground for mosquitoes and allow them to grow faster. St. Albans boasts trees, including cherry blossoms, Bradford pears, and honey locusts—the leaves that fall from them and land in standing water can also attract mosquitoes.

Waheed Bajwa, who heads New York City’s Office of Vector Surveillance and Control, said he doesn’t expect mosquito-borne diseases to be a large-scale threat in the near future, but that climate change has affected the breeding patterns of, and transmission of disease by, mosquitoes.

“Climate change is altering weather, and weather is creating more favorable conditions for mosquito breeding and also for disease transmission,” Bajwa said. “We can expect a longer mosquito season and…higher mosquito population during the season, and also higher numbers of hibernating mosquitoes during the wintertime.” He added that the city has a robust program to keep a large outbreak at bay.

A clear and imminent threat?

Although other experts agree that a large-scale outbreak isn’t an immediate hazard in New York City, many say the country is unprepared for a potential surge in infections from these types of mosquito-borne diseases. How the warming climate potentially affects infectious diseases, such as West Nile Virus, has been a topic of interest for researchers.

According to Alexander Keyel, a scientist at the New York State Department of Health Wadsworth Center and one of the authors of a study that predicted models of vector-borne diseases in New York and Connecticut, was surprised that future models would increase the spread of West Nile Virus upstate and possibly decrease it in NYC. However, he said these models can change with the climate and that NYC isn’t in the clear when it comes to mosquito-borne diseases. “There are other diseases that climate change likely will make worse for New York City,” he said.

Those other diseases to keep an eye on in the city include malaria, “and we need to have a better sense of where some of the Anopheles mosquitoes that spread malaria are, and how competent they are,” he said.

While officials in New York City remain confident about its measures to control the spread of mosquito-borne diseases, other parts of the country show the impact of getting caught flatfooted. In 2021, the largest outbreak of the virus in the country occurred in Arizona: More than 100 people died and more than 1,700 cases were reported in Maricopa County.

Last year, Florida saw high-profile malaria cases that caused concern in the state. The cases were the first to be transmitted within the United States in two decades. Because Florida is accustomed to mosquito-borne disease, it has the infrastructure to react quickly to an outbreak. But Sadie Ryan, a medical geographer at the University of Florida, said other states may not have the resources to allocate to a rapid response to an outbreak of arboviruses, including malaria, dengue, and the West Nile virus.

The U.S. is planning for the next possible pandemic, including vector-borne diseases such as the West Nile virus, and announced a strategy this month to work with other countries to respond to infectious diseases.

Ryan is concerned about a new species of malaria-spreading mosquito on the scene—a type of Anopheles mosquito that has left its range of India and the Middle East across Africa and kept moving to places such as Ghana and Nigeria over the past decade. “A lot of the Americas are very suitable for it,” Ryan said, adding that the mosquito is happy to establish itself in urban environments. According to the World Health Organization, the species is resistant to many insecticides currently used.

Illegal dumping has entered the chat

Residents in southeast Queens have long grappled with illegal dumping, which, along with being an eyesore, creates garbage that piles up and is also a health hazard, attracting vermin, including mosquitoes. In-between homes with landscaped lawns are abandoned houses with piled-up bottles, cans, mattresses, and tarps that attract standing water and other issues.

And they aren’t alone: A preliminary study in Baltimore found higher rates of West Nile Virus-infected mosquitoes in neighborhoods of color already struggling with environmental justice issues.

Shannon LaDeau, a disease ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, collaborated with the University of Maryland on the study and has also previously looked at the connection between disinvested neighborhoods and mosquitoes. She said mosquitoes are an easy entryway to think about the unhealthy consequences of illegal dumping.

Dumps of trash that include containers, such as purses, chip bags, or discarded cups, can hold water between rain, which can be a holding site for mosquito eggs between wet times. “Especially with ponding, that comes and goes, a lot of times, those containers hold the water in between,” she said. Wild grass that can grow on the lots of abandoned homes can also breed mosquitoes.

Public messaging about emptying standing water in containers in yards can fall flat if residents are dealing with larger infrastructure issues such as dumping and abandoned homes, according to Sarah Rothman, a PhD student who also worked on the Baltimore study and is studying the relationship between mosquitoes, plants, and income for her dissertation. “You can tell residents all day to check their properties, do source reduction, dump out their containers, but if they live next to an illegal dumping ground, that is not enough. That’s not going to be an appropriate strategy,” she said.

In Queens, dumping happens sometimes in broad daylight in public spaces such as the Hollis LIRR train station and also more hidden, private places such as neighbors’ alleyways, according to residents. “I have had neighbors who dumped the couch behind my garage and I have to go knock on their door and tell them to move it,” said St. Albans resident Vivolyn Dean-Brown, 60.

Last year, the city budgeted $7.5 million for its precision cleaning initiative, which includes removing illegally dumped trash.

Dumping and its inequitable impacts are not unique to Queens. Last year, the U.S. Department of Justice settled a lawsuit with the city of Houston over how it handles illegal dumping. Residents were vocal about environmental racism and have long complained that the city disregarded dumping in Black and Latino neighborhoods.

Combatting a nuisance

As early as June, New York City’s health department has used sprays from trucks to protect against mosquitoes carrying the West Nile virus. Residents are encouraged to stay indoors when spraying occurs in their neighborhoods. The department also sprays larvicide over marshes, wetlands, and other natural areas from low-swooping helicopters to kill baby mosquitoes. According to the department, it alerts communities where spraying happens at least 24 hours in advance. Spraying pesticides, which the city states are safe to use, can help keep West Nile Virus and other diseases under control. But for many residents, environmental and infrastructure fixes are also needed

In 2023, there were more than 1,100 mosquito pools where West Nile Virus activity was detected in New York City and a majority of those were in Queens.

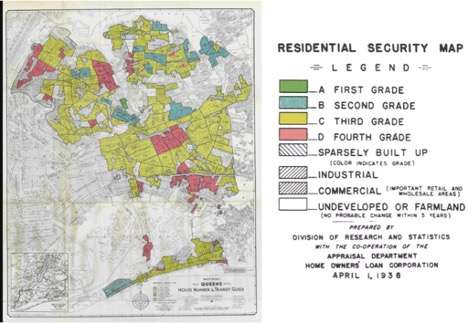

For a few residents in St. Albans, the effect of heavy rains is more than just ponding and the nuisance of mosquitoes. Dean-Brown moved to St. Albans in the early 1980s. Nowadays, the flooding behind her home in the alleyway creeps into her garage. The water also builds in her backyard and seeps into her basement, causing flooding and mold growth in her garage.

Last fall, her basement flooded during intense rain. She and her husband frantically used Tupperware containers and buckets to pour water into the bathtub and toilet to prevent the water from rising. “My husband had to call in from work that day to help with the bailing out,” she said. “It’s costly.

Dean-Brown has joined her local block association, along with Blaney, to help inform residents about the dangers of flooding in the alleyways. “The entire neighborhood will benefit with the alleyway being fixed—if they’re getting flooded, their flood will also stop,” she said.

Dean-Brown, Blaney, and other neighbors are organizing a fundraiser, as reported in the Queens Chronicle, to raise $300,000 to re-pave five alleyways in the neighborhood.

City resources for mitigation

Unlike other cities and counties, New York City’s health department does not provide free mitigation tools to alleviate mosquitoes such as mosquito dunks, minnows, or magnets, a department spokesperson told the Amsterdam News. The department didn’t answer specifically whether it looks for mosquitoes at dumping sites, but did say it keeps an eye on mosquito whereabouts and habits based on past activity, as well as where illnesses have been found.

Plans to protect New Yorkers from future storm surges and other disasters are essential. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has proposed a $52 billion plan for a series of sea barriers across the city, but residents and advocates say small-scale remediation, such as further reducing dumping and expanding government programs to help homeowners make fixes to homes in flood-prone areas, are also necessary to deal with rain.

Blaney and her neighbors aren’t waiting around for government help when it comes to the issue of ponding, although they also realize that there are some things that are just out of their hands. The everyday weather and human-accelerated climate change is one of those things. In the meantime, she and her neighbors have to deal with the buzzing bother of mosquitoes. When the rain dampens yet another opportunity to enjoy a day outside, she said there’s nothing else to do but wait for a sunny day. “I just let nature take its course.”

© 2024 Roxanne Scott

This story was made possible by grants from the Journalism & Women Symposium health fellowship supported by the Commonwealth Fund, as well as the Alicia Patterson Foundation.