Looking back, people say they didn’t much notice the two men – one fat and one thin – lurching along the unpaved roads in their gray 1980 Chevrolet pickup early on the afternoon of Tuesday, March 24.

Like most days in Huejutla, Hidalgo that time of year, it was hot, the humidity oiling in sweat anyone who happened to be out of doors.

Huejutla’s working-class Lopez Mateos neighborhood is made up of humble concrete-block homes and unpaved streets jammed crudely onto a hillside. The neighborhood is one where who owns the land is a question that can’t always be easily answered. Residents make any improvements, chipping in to install things like electricity because the city hasn’t stretched services to the area. There’s no drainage or public transport. When it rains, people walk to work in knee-deep water. A few mom-and-pop stores are what most people rely on for food.

Stopping frequently at these stores, the men would stay a couple of minutes. Then they would slowly climb into the pickup and roll off to the next one.

The men sold small packets of stamps, costing one peso apiece. In Mexico, children buy the stamps, stick them to special cards that, once filled, they redeem for prizes: toy guns, soccer balls, dolls. The men traveled through much of central-eastern Mexico hawking the stamps in poor working-class neighborhoods, but this was their first time in Hidalgo.

They were as poor as their customers. Jose Santes, 30, was an overweight father of four young children, who had given up taxi driving for the somehow more stable job of traveling salesman. Salvador Valdez, 23, recently married, had left an unpredictable seasonal job, orange picking, to accompany him. Both men hailed from Tihuatlan, a town of 25,000 people three hours away in the neighboring state of Veracruz.

Store owners remembered them only as simple traveling salesmen like dozens that pass through every month, and a little less pushy than most. The fat one was doing most of the talking. Of the 8 or 10 stores Santes and Valdez visited that day, only one — more an outside table than a real store — took any stamps.

The day would have ended with the two men drifting out of the neighborhood and out of mind had the salesmen not found themselves in the Lopez Mateos neighborhood about the time children were letting out of school.

Valdez was standing by the truck, while Santes was inside a store trying to sell to a merchant. A group of children, seeing the toys, gathered around the truck. As a joke, Valdez said later, he ran after the kids, grabbed a couple of them: Edith Hidalgo, 11, on the arm and Dolores Hernandez, 9, on a buttock. Valdez said later he was only trying to shoo them away from the toys in the truck. To Edith Hidalgo, he said something like, “What a pretty girl. When you’re older we’ll come back and kidnap you.” Terrified, the children shrieked and ran for home, reporting to their parents that someone had tried to kidnap them.

A neighbor heard the screams and called police. Officers stopped the men up a hill where they had continued on, unaware anything was amiss. Arturo Moreno, the region’s prosecutor, took the men’s statement that night. Santes denied doing anything at all. Valdez admitted what he did, repeating that he’d only been joking. “See where jokes have gotten you,” Moreno told him.

He couldn’t have imagined. That chance intersection of the children and the salesmen, leading to Valdez’s stupid but relatively minor remark, not uncommon in rural Mexico, was a spark that the next day would ignite a firestorm of rage. Yet even when it happened – that is, when more than 1,000 people finally lynched the two traveling salesmen in the town’s plaza the next night – so much had contributed to creating a voracious mob out of a peaceful demand for justice that what was surprising was that so many people could look back and say they didn’t see it coming until it came.

There was, for example, alcohol, which the region is known to consume in large quantities. Certain authority figures never intervened – notably the local police, priests and bishop, though the lynching took place in full view of city hall and the town cathedral. A local radio station assembled the crowd by airing a spot every 15 minutes urging people to the plaza to support a demand for justice.

There was the area’s profound poverty, ignorance and isolation. There was the long-standing tradition in the region of responding to community calls for help. Added to that was a spectacular regional gift for exaggeration; so when it was all over, the men were not salesmen at all, but foot-soldiers in a Texas-based ring of child kidnapers who not only trafficked in organs, but had a liver or two in their truck.

But above all, people acted on the belief that their society is unjust, and that it’s almost the authorities’ nature to free nefarious criminals, unless pressured to do otherwise.

And, who knows, a lot more than that probably went into the mix. In the chaos on Huejutla’s plaza it all festered and exploded in the tropical heat. Not even the governor, who hopped a mountain range in a helicopter late that night, could stop it. “This is a quiet town,” says Cristobal Cifuentes, a local dentist. “No one expected it to go as far as it did.”

Huejutla (pronounced Way-HOOT-la) is in fact a quiet town.

It sits on a northern edge of Hidalgo, one of Mexico’s poorest states just north of Mexico City.

Huejutla is only 133 miles from Pachuca, Hidalgo’s capital, but the distance is deceiving because between it and the capital is the massive Huasteca mountain range – culturally another world, similar in isolation and poverty to the Appalachian Mountains. Those 133 miles take about four hours by car.

Huejutla (40,000 pop.) is the political center of the Huasteca and commercial hub for dozens of small farming communities, where bony Aztec indians live from harvest to harvest. Agriculture lingers only by strength of habit. People here grow when it rains and lose what they’ve invested when it doesn’t. So Huejutla has become a magnet, as well, for poor campesinos, arriving like refugees from the battered fields and living in shantytowns radiating out from the center.

There is a bleakness about Huejutla — a deprivation and futility — as if all the tremendous effort the town can muster only adds up to life’s bare essentials. Illiteracy is high. Nightlife amounts to a small movie theater and an estimated 200 cantinas. Huejutla, though the seat of Hidalgo’s third most populated `muncipio,’ or county, has no functioning pay phone downtown.

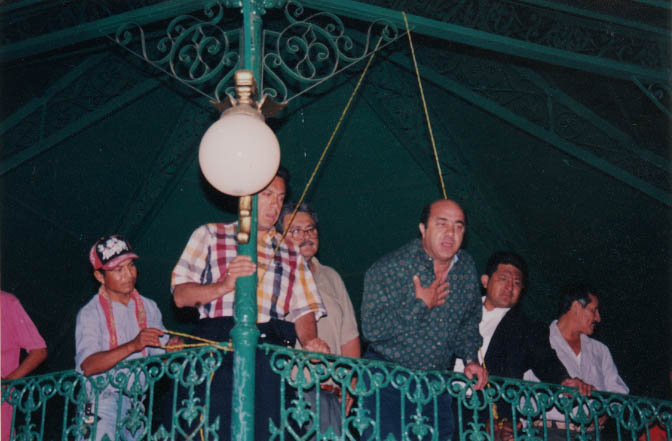

The central Plaza de la Revolucion sprawls pleasantly across three city blocks. To one side rises the town’s dark, beautiful 16th Century cathedral. Across the plaza is a line of shops – stationery stores, shoe stores, ice cream vendors – that lead down to city hall, the jail and the courthouse. Anchoring the plaza is a wrought-iron bandstand, painted forest green.

Last December, reports circulated that some children had been stolen from the annual fair. That never happened, but the stories are believed. Still, you can understand people’s awe at a sudden eruption of violence. Huejutla doesn’t have much crime, and this kind of thing had never happened before.

Nor was Prosecutor Arturo Moreno concerned when the Santes and Valdez case landed on his desk as he sat in his office that afternoon. After interviewing the two men, and looking objectively at the case, Moreno concluded he could only charge the men with attempted kidnaping. And under Mexican law, this meant bail.

In Mexico, anyone accused of a crime not legally deemed “serious” is eligible for bail. Serious crimes, in Hidalgo, are murder, rape, robbery, rustling and kidnaping, among others. Attempting to commit these crimes is, by law, not “serious.” Moreno set bail at 5,600 pesos (roughly $700) for the two men.

Arriving at the courthouse, however, the girls’ families were outraged to learn about the salesmen’s bail. These were kidnapers, being let free. Judge Anastasio Hernandez tried to explain the law. Finally he told the assemblage of about 15 people that the best he could do for them was raise the bail to 12,500 pesos. The family of Edith Hidalgo say they understood the bail concept well. “But you know these criminals pay bail and go out and do it again and again,” says Alfonso Hidalgo, Edith’s father.

Tempers flared, the crowd slowly grew and rumors spread. It wasn’t long before rumor had it that Santes and Valdez were caught with at least one girl in their truck. On-lookers were now being told a rough shorthand: two child kidnapers were going to be released for 5,000 pesos.

To the people listening to the judge that afternoon, it all began to reek of bought justice. And that sounded so familiar.

What they they believed was happening, and why they believed it, have a lot to do with the history of corruption in modern Mexico.

It starts with Mexico’s ruling party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which has held power here for 69 uninterrupted years, the world’s oldest one-party state. The PRI has achieved longevity by buying people off; it is a nationwide Tammany Hall and a remarkably successful one.

The price the ruling party has paid for loyalty is usually not high. But it almost always involves some way of getting around the law. The corruption for which Mexico is world famous is actually the oil lubricating a vast party machine. A great number of perverse results come from all this. But the greatest perversion is that of the justice system.

The PRI came to use the justice system as a lever to enforce support: those loyal to the machine could flout the law, while anyone who stepped out of line soon felt its full force. Accompanying this, naturally, was widespread corruption in law enforcement, where bribes can sway a verdict or can get a person out of jail early.

Mexico’s working classes know this. Without money for bribes, or friends in high places, they possess a fine sense of just how firmly the system is stacked against them. And so a vast folklore has emerged regarding the treachery of the “autoridades” — part fact, part fiction, but all of it believed and repeated as gospel truth. Thus, two child-kidnapers about to be released on bail would be taken for granted as another example of crafty authorities undermining the law for personal gain.

Obsessions with Crime

What’s more, the unpredictability of the justice system forced large swaths of Mexico’s working classes to organize, usually along neighborhood and occupational lines: teachers, cabbies, garbagemen, street vendors, campesinos. In these organizations they could protect themselves and, at times, force the system to allow them a chance to break the law. Leaders of these groups are similar to ward bosses. They have access to the system that members lack, so they can get things done — say, obtain street space for a vendor.

In Huejutla, these popular organizations, and their leaders, were particularly strong. On their word, members would close a highway or a community. They have been rumored to get people out of jail for a fee. “Sometimes if you don’t go to a meeting, they fine you,” says Maria Maya, owner of a taco stand and a member of the PRI’s Union of Street Vendors in downtown Huejutla. “We go to support our leaders and for unity.”

In addition, the Huasteca has a tradition of banding together to confront external threats. “For any kind of thing – a cyclone, an epidemic, a fire — people come together,” says Refugio Miranda, a teacher of the Aztec language. Miranda remembers in the mid-1980s a rumor circulated that a madman in the region was wandering around at night cutting off people’s heads. “All through the region, communities came together to protect themselves. Everyone went in groups. They’d go to dances in groups. They put guards on the highway.”

Communities respond especially fast, Miranda says, when the outside threat is posed by government authorities. “People automatically mistrust the authorities,” he says.

And so the Huasteca was bequeathed the following peculiarities relevant to the lynching of Santes and Valdez: a deep popular mistrust of the justice system and the promises of authorities; its corollary, which is that authorities will do nothing or, worse, will side with the rich and the criminal element over the hardworking poor unless pressured to action; and the traditions of strictly obeying leaders, coming together without questioning, and responding quickly to calls for community action.

And all of that convened in the next ratcheting up in the day’s events. Police say Alfonso Hidalgo paid for a spot at radio station XECY, across the street from the courthouse. The spot referred to child kidnapers going free for 5,000 pesos – with no mention of bail — and that “your child could be next.” The spot said nothing about mob justice, but it urged people to support the parents’ demands.

Radio is the Huejutla’s most important communication medium, since many residents are too poor to have telephones. XECY is one of only two local stations. Starting about 2 p.m. and lasting through the afternoon until about 6 p.m. or so, XECY aired the spot 16 times.

Sounding a lot like a call to community action, the spot turned the small collection of people into a massive crowd that by nightfall filled the plaza. “It was on the news,” says Maria Maya. “School teachers were telling children that they should go support the demand for justice. Plus, children are always being stolen. A couple were kidnaped at the annual fair in December. I think they stole like two or three.”

Off in Pachuca that afternoon, Attorney General Omar Fayad was at work in his office when he received a call from Huejutla’s Mayor Jose Luis Fayad, no relation. People were angry. So it was agreed: bail for the salesmen would be revoked.

By mid-afternoon, the crowd was growing and had barred people in the courthouse from leaving. Arturo Moreno called Attorney General Fayad. “Don’t worry,” he was told, “we’re not going to let them go until there’s a complete investigation.”

Moreno settled down to read some reports. Soon it would all blow over. Judge Hernandez went out again to tell people that the Attorney General had decided to revoke bail.

It’s doubtful enough people heard him to make a difference. And even if they’d heard, it’s unlikely many people would have believed him. The radio kept its drumbeat going, never reporting that bail was now revoked. Plus, one result of years of perverted justice is that Mexicans are simply unwilling to believe their public officials, or that the justice system ever works.

The following is a case in point: In Huejutla, two years ago, Jaime Badillo-Austria, a schoolboy and son of the owners of La Vega, the town’s best restaurant, was kidnaped. Finally, his body was found decomposing outside town. This is Huejutla’s only authentic case of child kidnaping in years.

The kidnaper turned out to be the boy’s 29-year-old half-brother. In something out of a Mexican soap opera, the half-brother was born of a rape of a maid by the elder Badillo years before. He grew up rejected by his father and resenting his half-brother. That, according to those who have spoken with him, was what brought on the kidnaping and murder. He is now serving 30 years in prison.

Yet few people in town remember justice being done in the case. Indeed, most people are certain that no one was arrested, and use the case to demonstrate to visitors their authorities’ ineptitude.

So just because Judge Hernandez said bail was now revoked didn’t mean anyone believed him. Moreover neither Moreno nor Judge Hernandez was born in the Huasteca – both hail from Pachuca, the far-off state capital – and no one knew them.

Late in the afternoon, Mayor Jose Luis Fayad met with a team of 40 delegates – essentially PRI neighborhood representatives. The delegates told the mayor that people didn’t believe the judge and that they were now hot, angry and getting drunk.

Fayad had spent the day at home. He says that the problem was not his jurisdiction, but belonged to state authorities and that anyway he had spoken on the phone with officials in Pachuca. Plus, he says, his 32-man police force, armed with only .22-caliber pistols, was unprepared to handle large crowds.

Getting toward dusk, Fayad made his first public appearance. From the city hall balcony, he guaranteed that the two salesmen would remain in custody in Huejutla. Meanwhile people insulted him from below and yelled at him to come down. Fayad went home, not appearing in public again until the governor arrived about 11 p.m. By then, the court, jail and city hall had been ransacked and the two salesmen were in the mob’s hands.

It was another of the day’s critical moments. Fayad, a man born in Huejutla, couldn’t sway the crowd.

Jose Luis Fayad had been a beloved member of Huejutlan society — a surgeon who often gave free consultations to the poor. But after taking office as mayor last year, he has since distanced himself from his constituents – which, people say, affected his ability to convince the crowd that night.

Many charge that nepotism has prevailed in the mayor’s administration. A brother-in-law is chief of police. A cousin was appointed municipal judge. A sister-in-law is treasurer of the family-assistance program. Fayad’s sister owns a building-materials firm that supplies the city’s public works projects.

“People know all this,” says Anibal Torres, a teacher, who is the mayor’s brother-in-law, as well as a political opponent. “If he’d had the moral authority of being an honest man, people would have paid attention to him.”

Moreover, he’s funded questionable public works projects: a horse-racing track – in a town where many roads are impassable – and a plaza renovation, pulling a couple dozen shade trees. Both projects were seen as luxuries that Huejutla could ill-afford.

Then came January 16. That day, Fayad gave his first “State of the City” speech, as required by law. He invited people from Huejutla and the surrounding communities to attend. Close to 4,000 people showed up, though the hall held only 1,000. His assistants erred in locking the hall doors. Seeing the chains, people thought they were being prevented from coming in. Having lost a day of work – tantamount to a day’s food — to come support their mayor, their mood turned sour. Soon a torrent of tangerines, oranges and tomatoes was arcing through the hall’s windows. Fayad finally had to burst from the hall, protected by security guards.

“Since then, people haven’t respected the mayor,” says Jorge Muedano, who worked in Fayad’s campaign as a photographer.

Fayad left the balcony on March 25 thinking he had resolved the situation. Instead, the possibility of a lynching was becoming real.

Lynching has a long rich history in Mexico. For centuries, communities occasionally rose up in spasms of mob violence against priests, tax collectors and other symbols of authority. In modern Mexico, the lynching has, if anything, grown more common.

The “linchamiento” is part of the Mexico tourists never see, hovering beyond the shimmering hotels of Cancun and the sunny hillsides of Cuernavaca, in benighted towns and pueblos where any justice that does exist is hardly blind. Dozens, perhaps hundreds, of “linchamientos” have taken place in the last few years across Mexico. Criminals, and an occasional police officer, have been tied up, beaten, shot, kicked, knifed, hacked, stoned, hung from basketball rims. In a small town in Veracruz in 1996, a crowd grabbed a man suspected of raping and killing a woman, gave him a quick trial, judged him guilty, tied him to a tree, drenched him in gasoline and burned him to death, videotaping it all.

The Mexican lynching is different from its Southern U.S. counterpart, which a powerful majority used to keep a defenseless minority in place. It differs too from the lynching in America’s Old West, which emerged in the absence of law.

Here, the lynching exists because the law exists, but serves only those with money or power to use it. The Mexican lynching is a bellow of rage by the powerless majority against protected criminals, corrupt cops and politicians — the horrifying, but not surprising, result of years of twisted justice – articulating nothing so much as the quality of justice Mexicans believe they can expect from their system.

Things began heading that direction shortly after the mayor’s speech. Someone set fire to the salesmen’s pickup. City police did nothing to stop it. The crowd found toys and stickers in the truck. They fed the rumors: the toys were used to lure children. “I left about then,” says Cristobal Cifuentes, the dentist. “I could see people were ready to do things they don’t ordinarily want to do.”

Next the crowd broke down the door to the small courthouse where Judge Hernandez, Prosecutor Moreno and a half dozen other workers were hoping to ride out the storm. Again police did nothing to stop it.

The night’s leaders began to emerge. At the head of the crowd now was a man named Martin Hernandez. Hernandez, 65, is poor, lumpy, balding and has a healthy appetite for sugar-cane rotgut. For years he sold herbs and religious candles by the cathedral. Now, drinking heavily, Hernandez rose from his anonymity for the one moment of notoriety in his life, leading the break-in at the courthouse.

“He had a large bucket filled with gasoline and he started splashing the floor with it, like it was water,” says Moreno, the prosecutor. “We were kind of huddled in the last little corner of the courthouse. He said, `Now you’re really going to get screwed.’”

Hernandez splashed gasoline on Moreno’s shirt and drenched Judge Hernandez. They and the rest of the courthouse employees made a run for it out the side door. Moreno said he ran through downtown and into neighborhoods he didn’t know and didn’t stop until he reached a government office on the opposite side of Huejutla.

Judge Hernandez wasn’t so lucky. The crowd chased him for three blocks, caught him, beat him severely and tied him up, though he was able to slip away later.

The courthouse sacked and burned, the mob poured into city hall. The crowd destroyed the city’s tax and payroll records and the births and deaths registry. Computers came flying out second-floor windows, to exploded below like ripe melons. Police guns were stolen. Several police officers escaped by jumping to the roof of an adjacent building.

Sometime around 9 p.m. the mob set to work breaking down the jailhouse door. Jailer Yasir Nochebuena remembers a continuous pounding on the door from early in the evening. Then rocks and Molotov cocktails began landing on the roof. The hammering outside grew frantic as the crowd used anything available – sticks, pipes, tubes, machetes — to rain blows upon the door. From outside, the crowd yelled at Nochebuena to open up or things would go badly for him. The jail door is imposing black steel and witnesses say it took an hour to finish the job. But shortly before 10 p.m. the crowd, led by Martin Hernandez, broke the lock and rushed in for Santes and Valdez. A while later they emerged leading the two men, now bathed in blood and gasoline. As people kicked them and stuck them with knives and machetes, the salesmen were dragged into the plaza.

Juan Ramirez, a 67-year-old campesino, was in the plaza about this time: “It was filled with people. They’d burned a car. There were fires and papers burning. The skinny guy (Valdez) was on the ground and people were kicking him and saying, `Let’s burn him.’ Then they said `Let’s tie him up.’ They began dragging him by his feet across the plaza. So I picked up one arm and another man picked up another arm so he wouldn’t hit his head. We took him up to the bandstand.”

People clogged the bandstand. The salesmen, fading in and out of consciousness, came to their wits’ end. Santes begged for mercy. The crowd began a medieval interrogation and both men started admitting to anything. Maria Maya, the taco vendor, remembers people asking Santes what he’d done with the children. “He said he had two children in Tihuatlan and that he trafficked them to Texas. He gave the names of people who were his buyers,” she says.

Martin Hernandez, according to witnesses later questioned by police, was standing over Valdez with a machete point under the man’s right eye. “Isn’t it true you trafficked in children and cut them open and cut their organs out.” Valdez said yes, and Hernandez jammed the machete in Valdez’s eye and flicked it out.

Meanwhile, back in Pachuca, Attorney General Fayad had been receiving urgent calls. Fayad called the office of Gov. Jesus Murillo Karam. Sometime about 9 p.m., as people were sacking Huejutla City Hall, both men were on a helicopter heading over the Huasteca. The trip was the culmination of a bewildering day in which the anger in Huejutla was a constant irritant in the distance but hardly anything that promised open rebellion. “I was in Pachuca and I didn’t understand,” Fayad says. “Finally when the governor decided to come here, I said, `What could have happened during this time to allow things to get to this state?’”

The governor, flanked by the Attorney General and the mayor, arrived at the plaza about 11 p.m. Looking out onto a carpet of contorted faces, Fayad remembers thinking, “How is it things got this bad?’ The crowd chanted `Justice. Justice.’ `The governor said, `That’s why I’m here.’ He said, `No one made me come. I’m here because I’m as upset as you are.’ There were more chants for justice. `That’s why I’m here,’ said the governor, `but we’re going to do justice the way it should be done. There are laws and we’re going to respect them.’”

In Mexico, people see their governor at election time and not much after that. Otherwise he’s like a prince in a far-off castle, to whom the people must go to ask favors. Now the mob saw a governor pleading with them. They began retrieving from their memory every affront, every injustice.

“What about Colosio?” someone cried, referring to 1994 PRI presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio assassinated in Tijuana, and whose killer is now serving 50 years in prison. Mexican popular opinion holds that other more powerful people set the killer up for the job. Dorisela Austria, the mother of Jaime Badillo-Austria, broke into tears and yelled about injustice in her son’s case. People yelled that they’d seen “little livers” (“higaditos”) in the salesmen’s truck. They screamed about the children supposedly stolen from the annual fair in December.

To the governor, the mayor and others, the comments were the final proof that the crowd had lost all reason. But the Colosio case nationally, like the case of Jaime Badillo-Austria in Huejutla, has melted into the popular mix of fact and fiction that leads Mexicans to assume that there is no justice.

The governor was finished. He had no microphone; the sound system had been stolen during the sacking of city hall. The crowd began with catcalls, mimickry and he left the bandstand. His aides would say later that the two salesmen were dead. In Santes’s case this may well have been true. With the governor gone, Santes, at least unconscious and with his hands tied above his head, was now hoisted like a pinata. But his weight proved too much for the knot and he slipped through it and onto the bandstand. Undaunted, the crowd tied the rope around his chest and lifted him above the bandstand’s wrought-iron railing, then swung him out over it. Again, his heavy body slipped through the knot and he dropped like a rock to the plaza floor below. There he stayed.

Valdez’s night continued a bit longer. Others on the stand lifted Valdez to the outside of the railing and tied him to it by his biceps. He hung there, splayed like Christ before the crowd.

“He was facing the crowd. Most of the time he was unconscious. Then he’d awake and scream with pain,” says Simeon Bautista, Huejutla’s chief agent for the Mexico Interior Ministry, who was summoned to the plaza about the time the salesmen were being hauled from the jail. “He tried to lift up his legs, to support himself on the bandstand railing, but it was impossible.”

Finally, someone put a noose around his neck and then cut the cords around his arms that held him to the bandstand railing. “He was left hanging there. They gave him a big pull to lift him above the railing and he died,” says Bautista.

As the crowd watched what it had done, there was some applause. In the midst of it all, a few people could be heard yelling “Viva Huejutla” and, in reference to Hidalgo’s soccer team, “Viva Cruz Azul.”

In the days following the lynching, Huejutla remained keen to believe all kinds of rumors.

One was that buses of folks from Tihuatlan, Veracruz were coming to revenge the killing of their native sons. After a television interview with Martin Hernandez in a hospital bed in Pachuca, another rumor quickly circulated that he was dead. Not true, but not so far-fetched. Shortly after the lynching, riot police from Pachuca finally arrived and broke up the crowd. They likely also gave Hernandez the beating that left him with a broken left leg, a massive scalp wound and deep purple bruises over other parts of his body. Hernandez told reporters that he was so drunk that night that he can only remember that he wasn’t in the plaza. “A lot of people look like me,” he says. The girls’ families are to blame for putting the spot on the radio, he says. As for his injuries, “maybe it was the police who beat me, maybe somebody else,” he says. “I don’t remember.”

Judge Anastasio Hernandez spent the days after the lynching at first recuperating, then hiding from reporters. Prosecutor Arturo Moreno was rotated out of Huejutla a few weeks later. He was due for a change anyway.

Exhausted and sheepish, as if after a cheap one-night-stand, Huejutlans face the task of both condemning and justifying what happened that night. Generally, this is accomplished by noting that their authorities are good for nothing, while insisting – though untrue — that the six people arrested for the lynching had lived in Huejutla only a short time. “Huejutlans would never do such a thing,” says one woman.

“Huejutla was a stage. The actors were from some place else,” says Mayor Fayad.

Huejutla’s Bishop, Salvador Martinez, issued a public letter decrying the lynching. He drew the parallel to the way Christ died and remembered Jesus’s defense of an adulteress about to be stoned to death by a mob (“He that is without sin among you”). He didn’t say why neither he nor his priests attempted to intervene in the same way.

Attorney General Omar Fayad’s office arrested six people and charged them with murder, assault, sedition and some other crimes, for which they are asking the maximum penalty of 30 years in prison. Among them are Martin Hernandez; Maria Maya, the taco vendor, and Juan Ramirez, the farmer.

“I think what some people wanted (that night) was a kind of Roman circus, where the crowd gives thumbs up or down to feed the Christian to the lions,” says Fayad. “They got one. As a civilization, it was truly retrograde to have this kind of spectacle in the plaza of a town.

“Violence is the theme of the end of the 20th Century,” he says. “The inundation of news reports gives everyone the impression that all of Mexico is in the middle of a crime wave. It’s not true. But it creates a general consciousness that can expand into a kind of collective psychosis, which is what happened in Huejutla. That night people were talking about an uncontrolled wave of kidnapings. What uncontrolled wave? In Hidalgo, there were no kidnapings last year. This year we’ve had two, nowhere near Huejutla, and they’ve both been solved.”

On April 15, Gov. Murillo Karam came again to Huejutla, this time to give his regional “State of the State” address. He said he was approving funds for riot police for Huejutla. He also praised the town for having the most beautiful plaza in the state.

On May 12, Omar Fayad went before the Hidalgo state legislature to say that nothing showed Santes or Valdez trafficked in children’s organs, were child kidnapers, or even had criminal records. He took time to note the impossibility of “little livers” surviving in the Huejutla heat.

Still, the case’s resolution seems unlikely to forge a new appreciation for the justice system. All of those arrested are working-class poor. “There were a lot of (merchants) there that night. Why aren’t they here?” says Marco Antonio Hernandez, a 25-year-old encyclopedia salesmen, who was seen in a picture on the bandstand that night, and is one of the six accused. “They’ve just picked up poor people. Why are we the only ones in here?”

Indeed, Jorge Reyes, a businessman and owner of XECY, avoided all legal problems by firing his news anchorman and cancelling the station’s afternoon news show that broadcast the spots.

Three days after the lynching, Tihuatlan staged a march behind the two caskets in the two men’s memory. Santes, especially, was well known for his and his family’s participation in the local cab-driver organization. Neighbors and friends insist that he was simply a hard-working man trying to support a family. His family is trying to adjust to the economic catastrophe his death represents.

Discussions of the case set off lengthy descriptions of public officials’ corruption and venality. “We’re poor,” says Filomena Santes, Jose’s sister. “We don’t have any money. That’s why this happened.” The natural assumption: anyone rich would have been protected that night, or wouldn’t have been in jail in the first place.

Meanwhile, the families of the girls in the Lopez Mateos neighborhood want very much to forget what happened. They say they never wanted a lynching. “We put them in the hands of the authorities,” says Antonio Hernandez, father of 9-year-old Dolores. “They were human beings. We just wanted them to be punished according to the law. Now we just want peace.”

© 1998 Sam Quinones

Sam Quinones is a correspondent for Pacific News Service in Mexico City. He is concentrating on lawlessness in parts of Mexico.