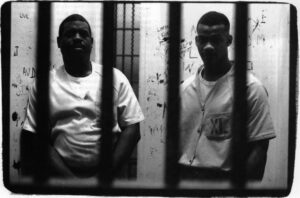

CHICAGO–“Oh, he’s a nice-looking young man,” Rose Doyle said softly, of the tall, muscular 24-year-old in jail togs who was being escorted into the courtroom by a sheriff’s deputy.

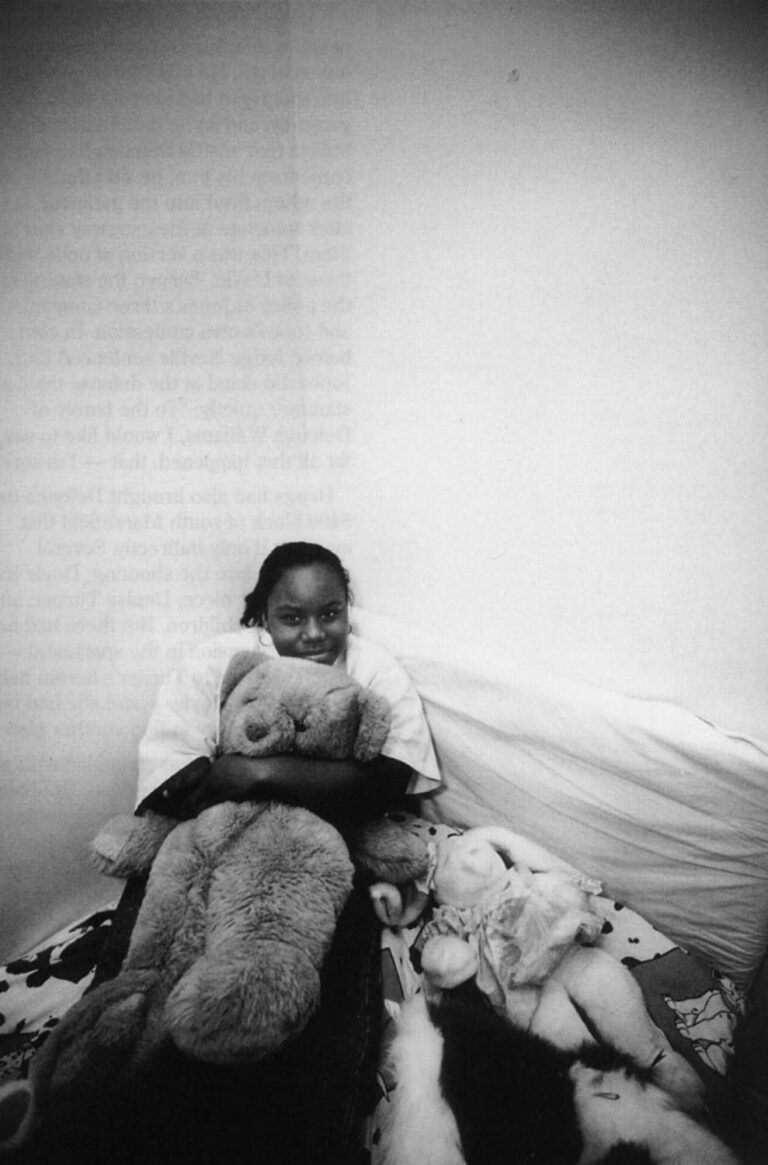

The man was Deron Jones. On the night of March 4, 1993, he pumped several bullets into a dark gangway on Chicago’s south side, in which stood the 43-year-old Doyle, her 34-year-old niece, Denise Turner, and her great-niece–six-year-old Delenna Williams. Delenna was struck in the chest and the wrist, and another bullet grazed her forehead, but she recovered. As Jones was ushered into the courtroom, Delenna was napping against Doyle’s shoulder, on the front bench of the spectators’ gallery. Doyle’s remark about Jones was directed at the women on the bench behind her–Jones’s mother, aunt, and girlfriend. “Don’t feel bad,” Doyle reassured them. “I got a big one just like him.” (Her oldest son has had his own troubles with the law.)

Photo by John Sundlof

A squabble between dope dealers had led to Delenna’s shooting. Jones didn’t know Doyle or her nieces. He told police he fired at them because he thought the women were buying dope from a rival dealer. “Is this what you’re looking for?” he yelled before opening fire, according to witnesses. He didn’t mean to hit the little girl, he told police. Actually, Doyle and her nieces had come to the block, from their home a half mile away, to see an apartment for rent on the back of the lot; it just happened that a tenant in the building in front was a dealer. Moments earlier and just down the block, Jones had shot another rival dealer in the arm. In March of this year he was convicted of aggravated battery for wounding that dealer, and of attempted murder for shooting Delenna. He was to be sentenced for those offenses this spring afternoon in the Cook County Criminal Courts building, on Chicago’s south side.

Delenna’s tragic past had made the crime even harder to stomach. She was 19 months old when a fire killed her mother and disfigured her and her brother, who was then three. Soon after Delenna turned three, her father was shot to death by a young man who wanted his Chicago Bears jacket. Reporters pounced upon the details of her misfortunes, and her telegenic grafted face and bald head made her, briefly, a media darling in this town. Less was revealed about the evil dope-dealer responsible for her latest misfortune. According to the prevailing sentiment, Jones ought to simply “be sent to prison for as long as the law allows, and then forgotten,” as one columnist put it.

Being a child, Delenna was beyond reproach–and thus the kind of victim that the press, prosecutors, and the public take comfort in: the kind that confirms the belief that crime is a matter of devils and saints, of bad people doing in good people.

“I don’t know what God has in store for Delenna, but it must be something special,” Assistant State’s Attorney Jennifer Borowitz told Judge Richard Neville, in arguing for a lengthy prison term for Jones. “She must be destined to do some great things, because in her short life she has experienced more pain, suffering, horror, and tragedy than most people will ever experience in their lifetime.” Jones, on the other hand, was “one of the most dangerous kinds of people,” Borowitz said, staring at him. “How frightening he is. How frightening for the human race.”

Photo by John Sundlof

But if everyone was supposed to fear and loathe Jones for what he had done to Delenna, the message somehow hadn’t gotten through to Doyle, Delenna’s guardian. There she was in the courtroom, consoling Jones’s relatives before the sentencing hearing began. And after Judge Neville–noting Jones’s lack of a criminal record–sentenced him to 20 years (a lot less than prosecutor Borowitz had had in mind, but more than Doyle had wanted), there were Doyle and Delenna in the hallway outside the courtroom, exchanging hugs and best wishes with Jones’s mother and aunt.

Families of victims and families of offenders don’t always see eye-to-eye. But in big-city felony courthouses such as this one, it’s not unusual for the people in the gallery to find they have more in common with each other than with the lawyers in the front of the courtroom. The spectators typically are members of the same racial minorities; they come from the same chaotic, dope-infested neighborhoods.

And if members of the victim’s cortege are not quick to denounce the offender, it’s often because some of them, too, have sat at that defense table, guarded by deputies. It’s hard to cast stones when you yourself have a rap sheet, or a loved one does. So while prosecutors thunder on about the demon who needs to be exorcised, the victim’s kin may be whispering in the gallery about another young person who got “caught up.”

Doyle is a social worker with no criminal background. But more than a few of her nephews and nieces have felony convictions–most of them for the possession or sale of drugs. The day Delenna was shot, Doyle’s oldest son had a date in this same courthouse on a weapons charge. Denise Turner, the niece who was with Doyle and Delenna the night of the shooting, served a year of probation in 1990 for possession. (But she and Doyle were indeed apartment-hunting that night according to detectives, who, after noting Turner’s record, checked out the story.)

Doyle’s heart sought vengeance in the first weeks after Delenna was wounded. But her feelings gradually mellowed. “We take more than just a little freedom from him if we incarcerate him for a long time,” she said two weeks before the sentencing hearing. “We take away a person who could contribute something.”

She wanted him to spend a few years in prison, probably no more than five, she said. If he had a drug problem, she wanted him to deal with it. She wanted him to get counseling so he could understand what he had done and so he would never do it again. She wanted him to develop job skills so that when he was released, he could earn a legitimate living and be less tempted by the money he could make from drugs. “I’d like to see him just–learn to be a caring individual,” she said. “Because that’s what we’re losing a lot of today.

“I believe everybody can change,” she said. “I have to believe that. If I don’t believe that people can change, then I lose already. I lose with my son. I lose with people I’ve known all my life.”

If offenders don’t seem to change that often, it’s because no one really tries to rehabilitate them while they’re doing their time, she said. “Someone needs to show them more alternatives, instead of just how to weight-lift. My kin folks who go to jail come back body-builders. They’re coming out with no skills, no jobs available; coming back to the same friends, same environment. And we want them to change? Can’t happen.”

What Doyle had hoped to gain from Jones’s trial was just a better understanding of why Jones did what he did–of what could have motivated him to fire into a gangway in which stood two women and a child. “But at this point, I’m not even sure that he knows why,” she said after the sentencing.

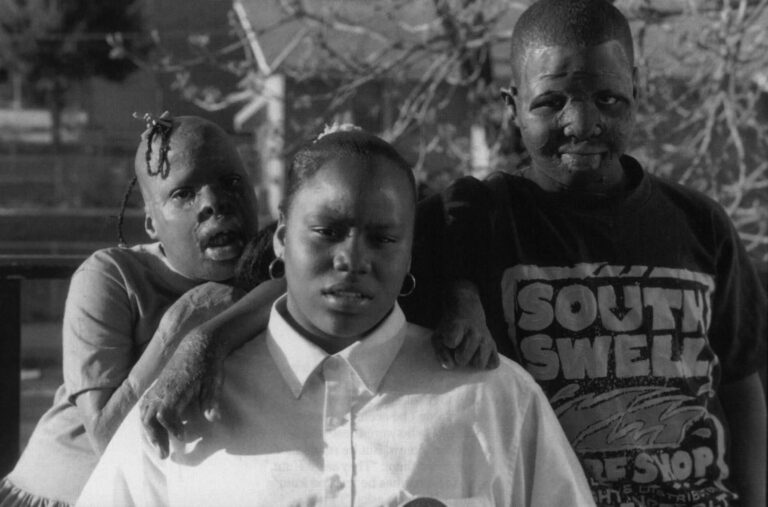

Photo by John Sundlof

Heroin is the reason Delenna is being raised by her great-aunt.

After Delenna’s mother died in the fire, she and her brother and sister were cared for by their grandmother. But the grandmother had a long-standing heroin habit, and so Derrick, 9, Keyata, 11, and Delenna wound up with Doyle.

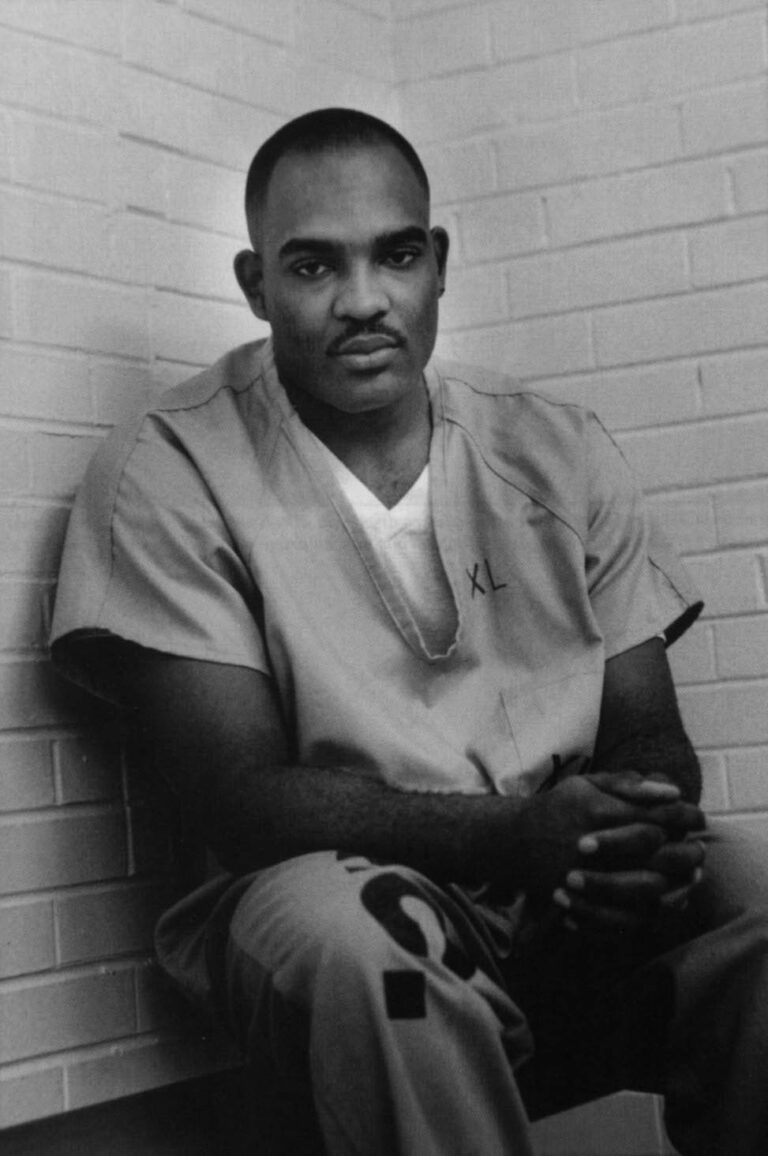

Because of heroin, Jones, too, was raised by his great-aunt. His mother had gotten hooked as a teen, before Deron was born. Deron’s father never figured in his life; he spent time in prison when Deron was young.

Deron “was born with drug in him,” said the great-aunt who raised him, 81-year-old Ollie Mae Brown. “He cried all the time. Didn’t matter what, he would just cry, cry. And at night he would cry, cry. And I said, it’s something wrong. And I carried him to every institution–to get that drug out of him. And the last one I carried him to, I got a letter–‘He is free of all drugs.’ Oh, I was so happy.”

Jones has an older and a younger brother, both of whom were raised by his mother and grandmother. Deron has always been bitter about being the one who was given away by his mother, Brown said. “He’d say, ‘How come she kept her other ones? If she had liked me, she wouldn’t have just gave me away.'”

Photo by John Sundlof

Every Sunday morning, Doyle gets Delenna and her siblings dressed up and takes them to church. Ollie Mae Brown always did the same with Deron. He was an usher and a junior deacon in his church as a youth, and he was still attending the church frequently up to the time he was jailed for the shootings. He had a paper route as a kid, and worked several jobs in high school and after he graduated. “Deron was a good child, he didn’t get into no trouble at all,” Brown said. But when he grew older he “got with a rotten bunch.”

Brown held the reins tight on Deron for as long as she could–a difficult task for a widow who was in her 60s and 70s when Deron was a youth. “I’d see him out in the street with a gang of boys, I’d say, ‘Come here, Deron,’ I’d say, ‘You ain’t got to be with them, they’re looking for trouble.’ He’d say, ‘Mama, I been knowing them a long time.’ I’d say, ‘You let them go ahead on.'” But as Deron matured, “He didn’t want me to call him away” from his friends anymore, she said.

Drug dealing is rampant in the impoverished south-side neighborhood in which Jones came up (and in which Delenna and her siblings and Doyle still live). Some time in the last few years, Jones hooked up with the neighborhood dealers. Friends and relatives knew what his fancier clothes and jewelry meant.

In Cook County Jail while awaiting sentencing, Jones allowed that he had indeed profited off cocaine, though he said he didn’t actually “serve”–stand on a corner dealing. Sometimes he stashed dope for the gang; he wouldn’t say what else he did to earn his pay. Drug dealing “wasn’t something I had to do,” he said. “But you look at your job situation, and I had just had a daughter, and–where are these Pampers, where is this food going to come from?” Since he wasn’t standing on a street selling, “I felt I wasn’t hurting a community or hurting somebody’s family, taking food away from somebody’s kids.”

He didn’t use drugs, he said. “You can never have your mind full of something and control your own life. And by me being separated from my original family because of drugs, that made me want to not use even more.” It did still bother him, he said, that he, and he alone, had been given up by his mother. “I always felt that I was the outcast.”

According to the statement Jones gave police, he and fellow gang members had learned that a pair of independent dealers in the neighborhood were selling cocaine in nickel-bags–$5-quantities–thus undercutting the business of the gang Jones belonged to, which sold nothing smaller than dime-bags. On the night of the shootings, according to the statement, he and three gang members set out to have a “talk” with these two dealers, both of whom lived on the 5400 block of south Marshfield.

Photo by John Sundlof

The first of these dealers–William Brundidge, nicknamed “Big Man”–got into a tussle with one of Jones’s companions in the entryway to his apartment, shortly after the four men came calling. Jones shot Brundidge in the arm because he thought he had a gun, he told police. (Brundidge did little to cooperate with police and ignored a subpoena for the trial, earning him six months in jail on a contempt citation from Judge Neville.)

After Jones shot Brundidge, the four young men ran. When Jones passed the home of the other nickel-bag dealer, he saw several people in the gangway, and assumed they were there to buy drugs, he later told police. So he fired a few shots at them. The three men who had been with Jones were also charged in Delenna’s shooting, but Judge Neville acquitted them, finding no evidence that they had had any idea Jones would fire into the gangway.

If Jones understood what brought him to shoot into the gangway, he wasn’t saying so in jail. He said that others with him that night had also shot into the gangway, and so he didn’t know if the bullets that struck Delenna had actually come from his gun; he said that he and the others fired into the gangway only after someone in the gangway shot at them. This was a version at odds with those of Doyle, Turner, the statements to the police of Jones’s three companions, and Jones’s own confession. In court, just before Judge Neville sentenced him, Jones did stand at the defense table and stammer quietly: “To the family of Delenna Williams, I would like to say–for all that happened, that–I’m sorry.”

Drugs had also brought Delenna to the 5400 block of south Marshfield that evening, if only indirectly. Several months before the shooting, Doyle had taken in her niece, Denise Turner, and her niece’s children. But there had been too much tension in the apartment–much of it due to Turner’s heroin habit, according to Doyle–and she had been urging her niece to find another place.

Doyle said she has struggled with guilt since Delenna was wounded. “If I hadn’t been so intent about my niece getting out, I wouldn’t have been out there trying to find a place for her. If I hadn’t been so single-minded about that, maybe I would have felt some warning of the danger. I’m usually aware of all my surroundings. I wasn’t alert enough that night.”

The criminal justice system could applaud itself for its response to the wounding of Delenna. Detectives had worked around the clock, and in a week they had arrested the shooter. He was convicted and sentenced, and will be off the streets for years.

But the guns are still blazing in Delenna’s neighborhood. Three weeks before Jones was sentenced, a 10-year-old boy was slain in a gang shooting six blocks from Delenna’s home. Five days after Jones was sentenced, another 10-year-old boy was gunned down in a drive-by shooting two blocks from her home.

The coke hasn’t stopped flowing, either. After Delenna and Brundidge were shot, police raided apartments on the 5400 block of south Marshfield, shutting down that street’s drug traffic. To this day, dope is not for sale there, according to Clarence Shearer, a longtime resident of the block. But elsewhere in the neighborhood, you can still buy a dime-bag of coke as easily as a newspaper. The block’s dealers were independents who “didn’t have any muscle,” Shearer said. “Other groups that have muscle may relocate–but they’re not going to close down.”

Donald Britton, one of the three men who was with Jones on the night of the shootings and who was acquitted, was dealing dope in the neighborhood again as soon as he was released from jail. “Got no job,” Britton, 19, said a few days before Jones was sentenced, as he stood in the vestibule of a building two blocks from where Delenna was shot. “Don’t nobody want to hire me. Can’t do nothing but sell drugs.”

Catching and punishing offenders is no easy task. But it pales compared with the job of addressing the underlying causes. Doyle speaks of the need for improved schools, more constructive recreational opportunities, better role models. “The courts can remove some people,” she said. “But does that really solve the problem?”

Photo by John Sundlof

“What can the courts do?” said Deron Jones’s aunt, Diane Bradley. “This is a family thing. Our men need to stand up and be responsible. It’s just so many broken homes and single parents and–so much drug abuse amongst our people! It’s almost in every other household. The children have no reason to respect the older people because the older people are going to the younger people to buy the drugs. It’s crazy, but that’s what’s happening.”

The day after Jones was sentenced in the courthouse, Delenna’s Aunt, Denise Turner, had a date in the same building, in a courtroom three floors below. In February, she had sold two dime-bags of cocaine to an undercover cop, and she was facing charges.

@1995 Steve Bogira

Steve Bogira, a writer with The Chicago Reader, is examining felony courts and the disadvantaged.