A spirit of optimism about children created the nation’s first juvenile court, in Cook County, Illinois, in 1899. Kids who got in trouble were still kids, the prevailing thinking went, and the focus ought to be on reforming instead of punishing them.

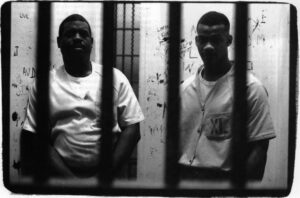

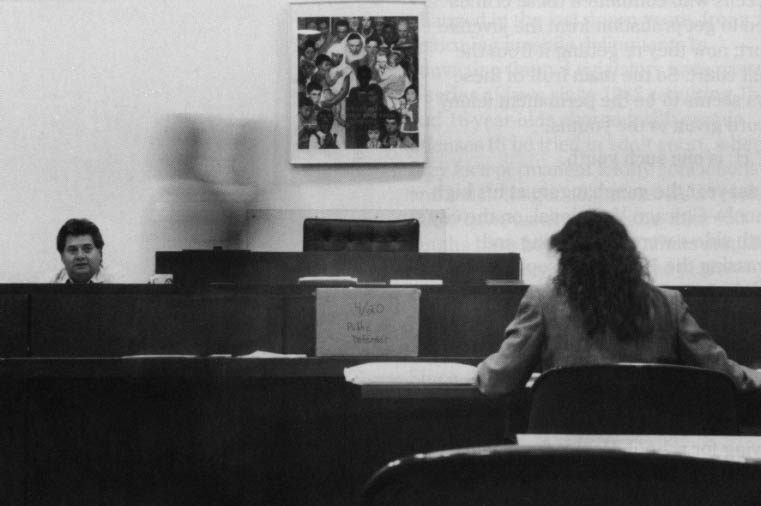

© 1993, John Sundlof, all right reserved.

Youths who seemed beyond rehabilitation could still be tried as adults in Illinois, as long as they were at least 13. Habitual offenders, and those who committed particularly heinous crimes, were transferred to adult court on the petition of the state and a juvenile court judge’s okay. Such transfers occurred rarely, in keeping with the philosophy that those younger than 17 were amenable to change, and ought not, in most cases, be treated like adults.

But the emphasis in Illinois has changed in the last dozen years, from reforming juvenile delinquents to convicting them. Legislators have passed a series of laws since 1982 requiring 15- and 16-year-olds charged with certain offenses to be tried in adult court, where they face permanent felony convictions and much longer sentences. As a result of these laws, on average more than 450 youths have been tried as adults annually in Cook County the last three years–compared with an average of 44 a year in the `70s.

Illinois is not alone in this regard. Since 1978, at least 41 states have passed laws making it easier to ship juveniles to adult court.

Juvenile courts were designed “with a different kind of juvenile in mind than we face today,” Cook County State’s Attorney Jack O’Malley says. “People weren’t thinking of hundreds and hundreds of 14- and 15-year-old murderers. We’ve got to take this alarming rate of juvenile homicides more seriously.”

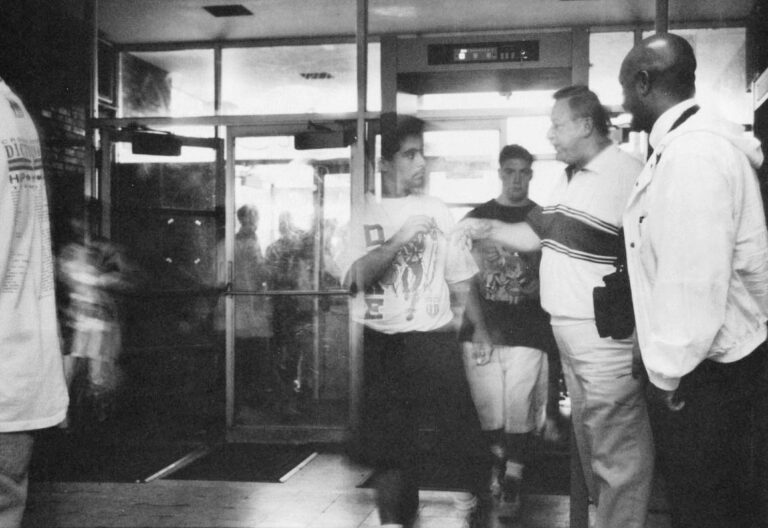

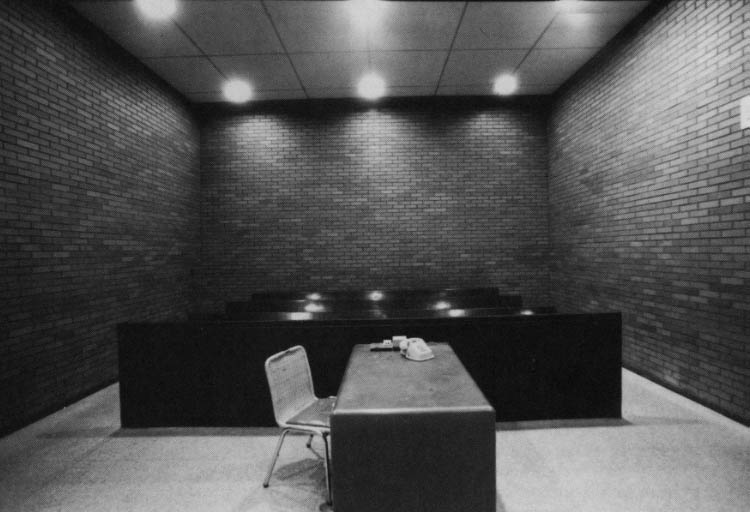

© 1993, John Sundlof, all right reserved.

The rate of murders by kids has indeed been skyrocketing across the country. According to the National Crime Analysis Project of Northeastern University in Massachusetts, the number of 17-year-olds arrested for murder climbed 121 per cent in the latter half of the `80s; the number of 16-year-olds by 158 per cent; and the number of 15-year-olds by 217 per cent.

In 1982, legislators in Illinois passed a law requiring adult court jurisdiction for all 15- and 16-year-olds charged with murder, rape, or armed robbery with a firearm. Before that law passed, 15- and 16-year-olds found “delinquent” on a murder charge by a juvenile court judge typically were jailed for two-and-a-half years. In no case could they be held beyond their 21st birthday. Now, those same juveniles usually face 20 to 60 years from an adult court judge. (They serve their sentences in juvenile facilities until at least their 17th birthday.)

“There’s absolutely no evidence that the security of the public has been enhanced by these mandatory transfer laws,” says Thomas Geraghty, director of the Northwestern University Legal Clinic, and a veteran juvenile defense attorney in Cook County. “I think what happens in some of these cases is we wind up putting people in the penitentiary who are salvageable. We spend a lot of money keeping them in the penitentiary, and when they get out they’re not going to be productive citizens.

“I think we’re getting to the point where we realize that we can’t just continue to build more prisons,” Geraghty says. “Our prison population is exploding, and we’re going to have to consider alternatives. And if we’re going to consider alternatives, it seems to me the target group ought to be the younger people.”

But Gina Savini, an assistant state’s attorney who prosecutes cases in Cook County’s juvenile court, says: “I hear a lot of liberal opinions–‘Save the juvenile, save the juvenile,’ but–when’s someone going to talk about the victims of juvenile crime?”

In Illinois, 13- and 14-year-olds charged with serious crimes still can be sent to adult court only if a juvenile court judge grants the state’s petition for such a transfer. (The judge grants the petition in about half the cases.) Savini frequently has to meet with mothers whose sons have died at the hands of a 13- or 14-year-old, to explain this discretionary-transfer process. Then she explains what will happen if the state loses on its petition: that even if the youth is found “delinquent” on the murder charge in juvenile court, he most likely will do no more than 30 months.

“And then the parent goes nuts,” Savini says. “She says, `This kid killed my son, and you’re telling me that in two-and-a-half years he’s going to be free to do whatever he wants? He’s not going to have a criminal record? This is just going to be a juvenile thing? Murder before you’re 15 means it doesn’t follow you around for the rest of your life?’ `Yes, Ma’am, that’s what I’m telling you. I don’t like the law any more than you do.’

“I see juveniles given break after break after break,” Savini says. “If they’re old enough to pick up a gun and shoot it, they’re old enough to take responsibility for their actions.”

Illinois juveniles today are facing adult penalties for more than violent crimes. Several times since 1982 the legislature has expanded the list of offenses for which 15- and 16-year-olds are automatically transferred to adult court, adding certain drug and weapon crimes. In the years 1975 through 1981, according to one study, fewer than 10 youths total were tried as adults in Cook County for nonviolent offenses; last year alone, the number was 184.

Democrats and Republicans alike have backed these automatic transfer laws. In floor debates, they have decried the “leniency” of juvenile court judges, and have spoken of the need for “stiff terms in prison” for 15- and 16-year-olds accused of the drug and weapon crimes.

But if they believed that trying kids as adults for these offenses would result in juveniles doing more time, legislators aren’t getting what they bargained for.

Of 57 youths in Cook County charged with drug or weapon offenses and transferred to adult court during a three-month period (January through March of 1992), only three received sentences of incarceration, according to Cook County Circuit Court records analyzed by this reporter. Prosecutors dropped charges in 17 of the cases; judges threw out another seven. Two youths were found not guilty; one was conditionally discharged. Two more cases were still pending. The remaining 25 youths plead guilty or were found guilty, and were sentenced to probation.

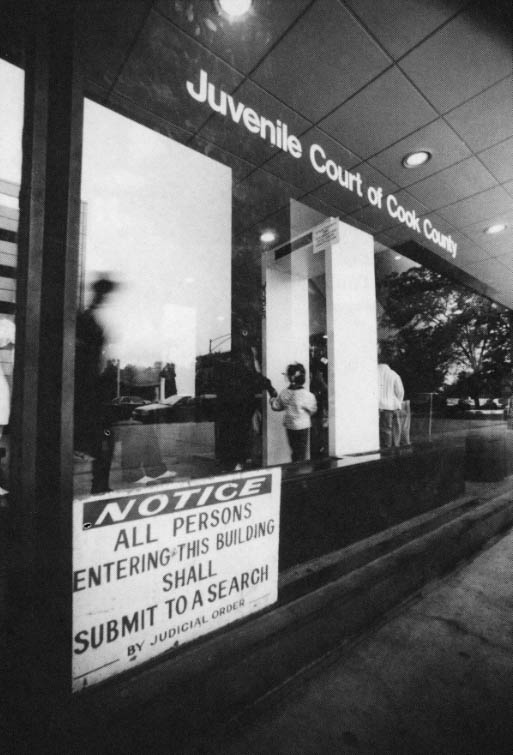

© 1993, John Sundlof, all right reserved.

Teens who committed these crimes used to get probation from the juvenile court; now they’re getting it from the adult court. So the main fruit of these laws seems to be the permanent felony record given to the youths.

C.H. is one such youth.

Last year the gangbangers at his high school–Chicago Vocational, on the city’s south side–were threatening and harassing the 16-year-old sophomore. C.H. just wanted them to leave him alone.

One morning–after a particularly distressing run-in with his tormentors the day before–C.H. took an unloaded revolver from his grandfather’s dresser and put it in a jacket pocket before leaving for school. He put five bullets in another pocket. He wanted the gangbangers “to feel the way they were making me feel–scared.” He had no intention of using the gun, he says; he’s not sure why he took the bullets. The whole thing was “a last-minute decision,” he says.

When C.H. reached school, he discovered that police were conducting a weapons search that day. He stepped out of line before going through the metal detector, told an officer what he had on him, and let the officer take the gun and bullets from his pockets.

C.H. had never before gotten in trouble with the law–not for so much as a curfew violation. He worked part-time after school at a chicken restaurant; on Saturdays he wrote stories in a journalism class offered by a local newspaper; on Sundays he sang in the church choir.

But because of the automatic transfer law, C.H. was convicted last October in an adult court of unlawful use of a weapon. The judge gave him probation. Nonetheless, it made the 16-year-old a convicted felon.

“I regret that I did it,” C.H. says. “I should have tried to go about it some other way. But I had never done anything wrong before. I don’t think I should be beat down for one mistake I made in my life.” He worries that prospective employers later in his life may learn about his record and be unwilling to hire him.

C.H. now says of the court system, “I don’t care for it much. It seems they just want to bring out the negative part, they don’t want to bring out the positive part of me.”

His family is appealing the conviction. “He’s got things going against him already–he’s black and he’s male,” his mother says. “He doesn’t need a record. Maybe if it’s a white kid, having that record wouldn’t make a difference. But let’s be realistic–black kids are having a hard enough time as it is out here getting a job.

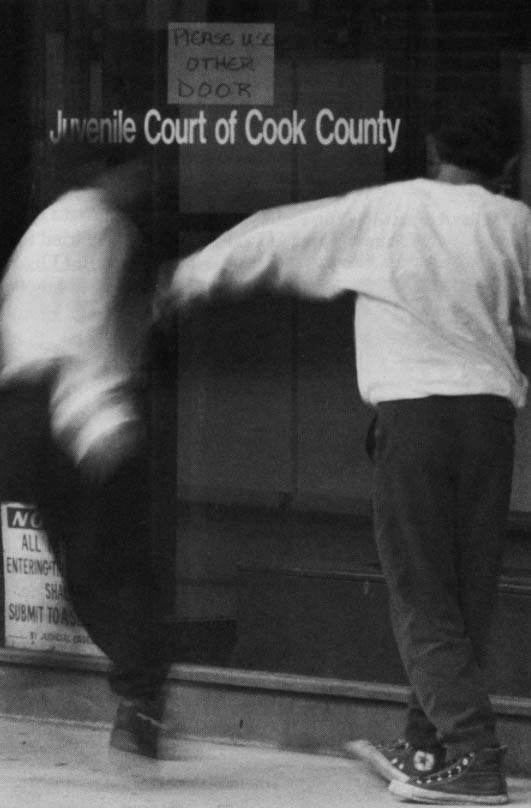

© 1993, John Sundlof, all right reserved.

“I don’t justify what he did, because it was wrong,” his mother says. “He made a stupid mistake. The question is: Do you give a child a chance when he makes one mistake? Or do you just label him because that’s what you can do?”

According to State’s Attorney O’Malley, “This notion that a kid who commits some offense is going to be marked for life is a lot of bull. If it’s on his record, that doesn’t mean he’s automatically never going to be able to get a job.”

But it often makes it a lot harder, according to a recent study by Harvard economics professor Richard Freeman. Freeman found that a felony conviction and a sentence to probation significantly harmed job prospects, with the effects lasting as much as a decade later.

In Cook County, juveniles tried as adults and sentenced to probation are assigned probation officers from the adult probation department. Juvenile probation officers typically have 40 clients; adult probation officers have 105.

State’s Attorney O’Malley says he didn’t realize that juveniles sentenced to probation as adults were assigned to the more-beleaguered adult probation officers.

According to Bob Shepherd, a law professor at the University of Richmond Law School and a consultant to the National Coalition of State Juvenile Justice Advisory Groups, many states have passed automatic transfer laws “without fully considering the consequences.”

Shepherd is a member of a legislative task force in Virginia that has been assigned what he calls the “radical” task of examining juvenile crime trends and the transfer issue before that legislature tinkers with its laws. States which haven’t hesitated to “get tough” with juveniles also haven’t paused to study whether trying kids as adults actually reduces juvenile crime, Shepherd says. And there is growing evidence, he says, that it doesn’t.

Jeffrey Fagan, a professor of criminology at Rutgers University, has found recidivism rates to be higher for teens adjudicated by adult courts than similar teens tried as juveniles. In his 1991 study, Fagan looked at 15- and 16-year-olds arrested for robbery and burglary in New Jersey and New York. The youths were identical demographically and had similar backgrounds in terms of delinquency. But the New Jersey teens were dealt with by juvenile court and the New York teens by adult court. Fagan found that the youths who were sanctioned by the adult court got rearrested more often and after shorter crime-free intervals.

© 1993, John Sundlof, all right reserved.

“Many states would like to further open the doors to the wholesale transfer of kids to adult systems,” Fagan says today, “but the fact is it does no good at all. In fact it probably does more harm than good.”

Minority youth are being transferred to adult courts in disproportionate numbers, according to Bob Shepherd. This is particularly true in states, like Virginia, where judges decide who gets transferred, he says. The task force he is a member of found that 69 per cent of the juveniles transferred to adult court in Virginia were minorities, even though minorities were only 42 per cent of those charged with transferable offenses.

But automatic transfer laws aren’t necessarily colorblind, either.

In 1990, Illinois mandated adult trials for all 15- and 16-year-olds caught peddling drugs in public housing projects. The population of public housing projects in Chicago is 98 per cent nonwhite. As a result of the law, a 15-year-old housing project resident with no delinquency record is automatically tried as an adult for this offense; while a 15-year-old caught selling drugs in his white Chicago suburb, or his white downstate community, will be tried as a juvenile, even if he has a long rap sheet.

In January, defense attorneys for two youths accused of selling drugs in a Chicago housing project asked a Cook County criminal court judge to find the housing project law unconstitutional. The lawyers presented evidence indicating that every single youth who had ever been transferred under the state law had been a minority–the vast majority of them black. Judge Michael Getty found that “the impact of automatic transfer for public housing offenses has been exclusively borne by poor people of color,” and granted the defense’s motion.

The state has appealed Judge Getty’s decision, and the case is presently before the Illinois Supreme Court.

State’s Attorney O’Malley says project residents he has met with “overwhelmingly” support the law, because they see it as a tool to fight dope-dealing and other crime rampant in many projects. Project residents are suffering with a level of crime that is “inconceivable” to the “ivory-tower paternalists” who oppose the law, O’Malley says.

Betsy Clarke, a legislative liaison for the Cook County Public Defender’s office, thinks legislators bent on adult prosecution of juveniles “aren’t willing to look at the hard issues: What should we be doing about jobs, education, and housing? “We’ve had this get-tough policy for some time now, and crime has gotten worse throughout the country,” Clarke says. “That’s because the root cause of crime is poverty, not lack of punishment. And until we address the root cause, we aren’t going to make any progress.”

@1993 Steve Bogira

Steve Bogira, a freelance writer in Chicago, is examining felony courts and the poor.