CHICAGO–A tale of two junkies:

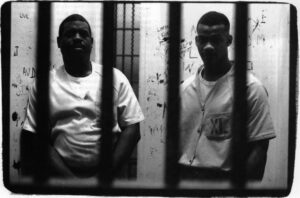

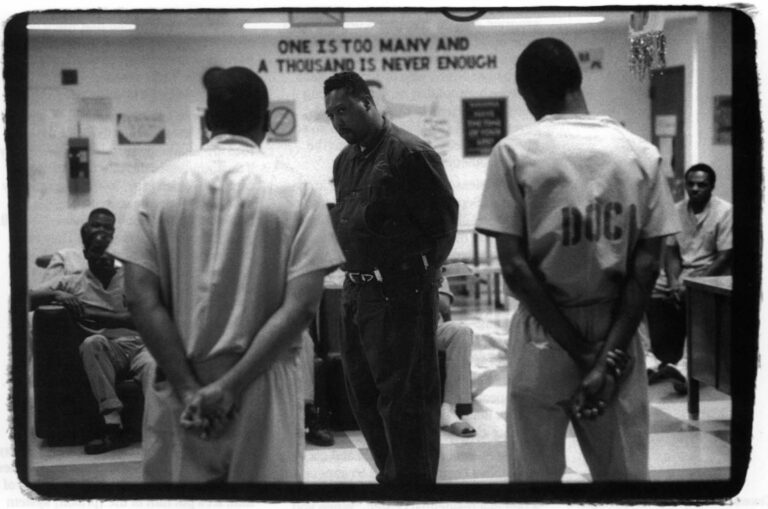

Dwight Walker sat in his cell in the Cook County Jail last September, aching, cramping, and spitting up, and worrying about how much time he’d get for his robberies.

Photo by John Sundlof

Walker, 27, craved heroin–as he has most of the time since he first snorted it, at age 20. He longed for a hit of cocaine, or at least a pint of wine. His addictions had landed him here, and now he was paying double.

Walker had bought his dope with money he got from selling gold chains to a jewelry store in the slum he lives in, on Chicago’s west side. He and a friend would get the chains by snatching them off necks. “We’d get a chain and drop it [sell it]–get 40, 50 or $60–go spend it on half-and-half–coke and dope [heroin]. Go right back out, take more jewelry, go and drop it, get half-and-half, coke and dope. We’d do it sometimes literally all day, or half a day–just doing drugs, up and down.”

One night last August, he yanked a chain off a man on a bus, jumped off the bus and ran; but a squad car happened to be nearby, and he got caught. In a lineup at the police station, a woman identified Walker as the man who had snatched her chain a month earlier. In both robberies, Walker had displayed what he calls a “shank” — a spoon with its head broken off that Walker used to persuade victims not to resist; so he was charged with armed robbery.

Walker started smoking grass and drinking in his mid-teens. Most of his friends were doing it, and he wanted “to blend in.” When he was 17 or 18, he began drinking cough syrup and downing pills; this was “the neighborhood thing.” He graduated to heroin, and when the neighborhood moved on to crack in the late ’80s, so did he.

Friends taught Walker how to climb up to the railroad tracks just west of the public housing project in which he lived and bust into freight cars. He sold his take–lamps, chairs, radios, tape recorders–on the west side, brought his money to the dope man and got high. Later, he advanced to the chain-snatching.

Walker has “messed up a few relationships because of dope,” he said. “I might have a little job supporting myself, then I mess up and lose the job. Then I’m laying on what my woman has. She start off giving money to support it–but, you know, that wasn’t what her money was for, and we would fall out.”

Twice Walker was convicted of crimes–a burglary and a robbery–that he committed to feed his habit, and he served short sentences. This cleansed his system of drugs, but it didn’t change his appetite; he resumed using as soon as he was out. One time he was freed early into a work-release program, which led to a job with a recycling company that paid decent wages. This new prosperity only let Walker get high “even better than I was before,” until he lost the job.

Both of the judges who sent Walker to the pen could have instead given him probation, and ordered him into a drug abuse treatment program. His early rap sheet–arrests for possession of marijuana, theft, trespass to property–screamed DOPE FIEND.

Armed robbery, however, is not subject to probation, and so now Walker faces heavy time–six to 30 years for each robbery. His public defender told him he’d try to get him a six- or eight-year sentence, but to expect 10 to 15.

At $16,000 a year, Walker’s penitentiary time has already run taxpayers more than $40,000. If he gets, say, a dozen years this time, and is paroled in six, taxpayers will still be spending nearly another $100,000 to confine and feed Walker. And while he vows, “I’m through with drugs now,” he allows that without treatment, he probably will return to the same pastimes. And treatment in prison, in Illinois as in most states, is not likely. Studies indicate that 80 per cent of the nation’s prison population has a history of drug and alcohol abuse. The bare fact is that Illinois has 300 beds for substance abuse treatment for its 34,000 prisoners.

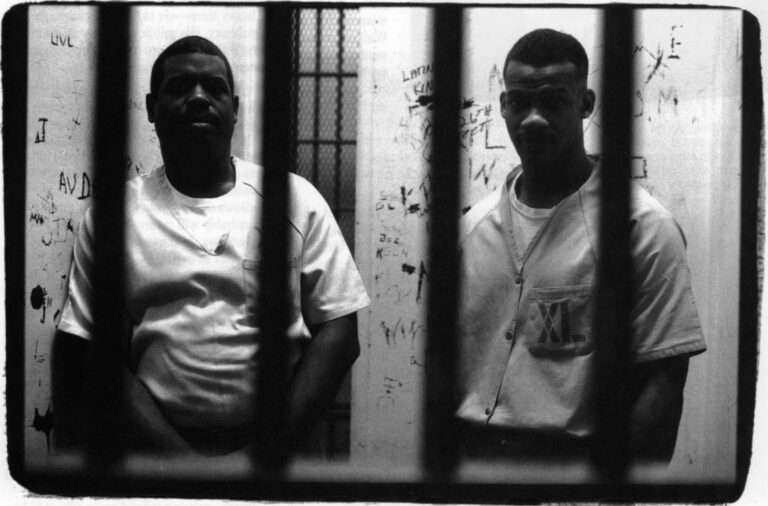

While Walker idled away in custody, Robert Grandberry was cooking meals at a French restaurant in a downtown hotel during days and at a drug abuse treatment center most evenings.

Grandberry, 40, who also grew up on Chicago’s west side, started sniffing glue at 13. At 15, he was “dropping Christmas trees”–popping red-and-green pills; at 17 he was snorting heroin, and by 18 he was shooting it. Later, he got hooked on cocaine.

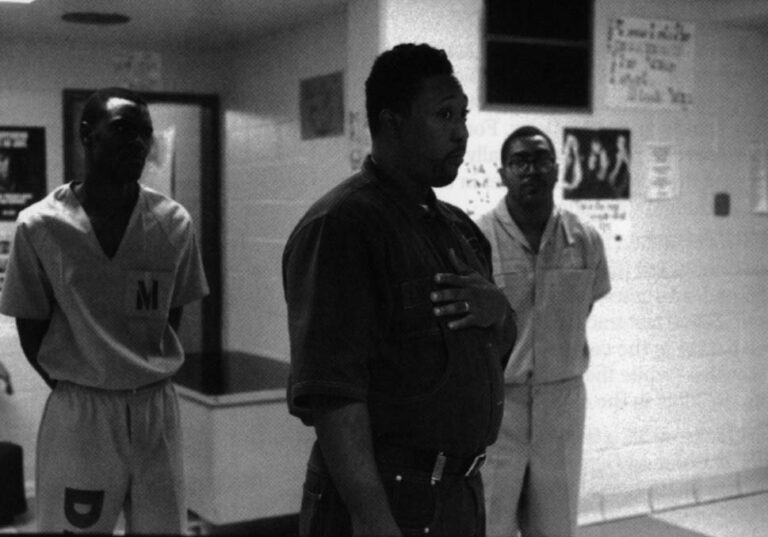

Photo by John Sundlof

Grandberry supported his dope habits by stealing bikes, snatching pocketbooks and breaking into stores and cars. He served four short prison sentences in the ’70s and ’80s. “Everytime I had gone to court it had been routine–take this cop-out [plea bargain] and go to the penitentiary,” Grandberry said. Whenever he got out of prison, “the very first thing I did when I got off the bus was went and got me some dope.”

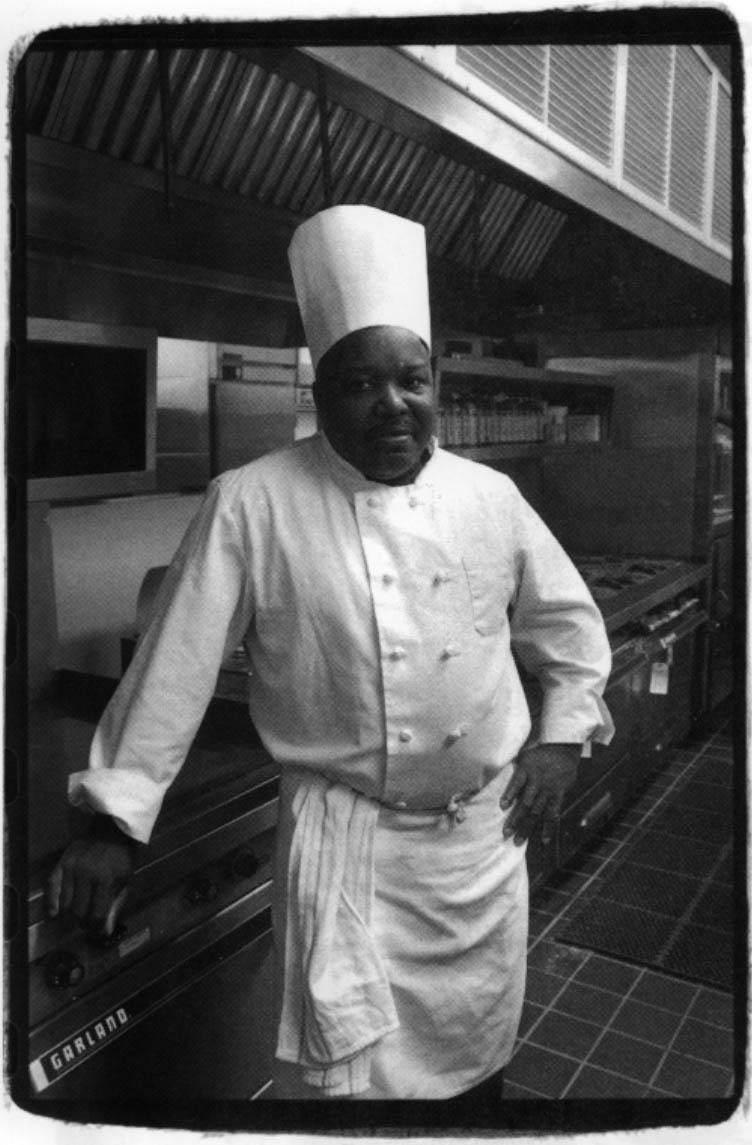

After he was released the last time, in 1988, he was arrested three times in three months for car thefts. A computer happened to kick those cases into the courtroom of Cook County Circuit Court Judge Michael Getty.

Photo by John Sundlof

Getty gave Grandberry a choice: 18 years in the penitentiary, or five years’ probation, and however much drug abuse treatment he needed to kick his habit. The judge made it clear to Grandberry that if he chose the probation but failed to comply with all aspects of his treatment, he’d get the 18 years in prison, plus perhaps more for violating probation. Grandberry chose treatment.

“I never thought in my wildest dreams that a judge would take a chance on someone like me,” Grandberry said recently.

Grandberry spent a year in a residential treatment program. He found treatment to be no picnic, and there were times when he considered skipping out. But the long sentence that hung over his head–and the faith Judge Getty had shown in him–motivated him to persevere. He completed treatment in 1989, and has been clean of drugs for five years. Instead of costing the public money, “I’m .paying. taxes,” Grandberry said. He laughs, and refers to the two jobs he holds. “A .lot.of taxes.”

If the nation could somehow purge itself of crimes committed because of drug addictions, states would be closing down prisons. Urine tests in jails across the country have shown two-thirds to three-quarters of defendants were under the influence of an illegal drug at the time of arrest.

A host of studies during the last decade have indicated that treatment, when accompanied by rigorous follow-up and careful monitoring of the recovering addict, can help addicts kick their habits, stay clean, and leave their criminal careers behind.

Most criminal court judges, though, rarely look to treatment programs as a sentencing alternative–for several reasons. Addicts typically deny they have a drug problem, and so identifying and treating them is not easy. Treatment doesn’t always work the first time. The crimes committed during relapses can haunt a judge who has to run for retention. Some judges believe in treatment, but are hamstrung by long waiting lists of treatment programs. The safest choice for a judge–even if it is costlier to taxpayers in the long run–is to send the addict to the pen.

Getty is one of the small minority of judges who manage to overcome the obstacles.

“I have a deep respect for Judge Getty–and that’s something I never had for a judge,” said recovering addict Ed Buckley, 39. Buckley was in and out of prisons for two decades before he happened to come into Getty’s courtroom, in 1990, on a burglary charge. He was addicted to heroin and cocaine; he took Getty’s offer of probation and treatment, and he has been drug- and crime-free since. He now works full-time as a counselor in a treatment center. “I was mostly a thief–and I was doing it to get more money to get more drugs,” Buckley said. “I was not a murderer or an armed robber or a rapist. Judge Getty was able to see that my crimes were drug-related. He takes a personal interest in every individual who comes through his courtroom, and that he gives probation to. He will support you in what you do, and he makes a personal check on you. I’d been in the court system for 20-some years, and I’d never been treated like that.”

Getty has a standard big-city court call: accused murderers and rapists appear before him, as well as burglars and thieves, high-rolling and penny-ante dope dealers, and those arrested simply for possession. A judge since 1983, he has long believed in substance abuse treatment for non-violent criminals. He has steered many veteran felons, like Grandberry and Buckley, into treatment, using the threat of long prison terms. Getting novice criminals, who aren’t facing so much time, to agree to treatment has often been harder. In 1989, he found a way. That year, he attended a conference in Philadelphia for judges concerned about how the legislative war on drugs was clogging the courts. On the plane ride home, he developed a protocol for his courtroom that he named “fast-track.”

Under the fast-track system, defendants are given the option of pleading guilty at their first or second appearance before Getty, in exchange for a sentence of probation. Defendants with a documented history of violence, or who are accused of using a gun in the charged offense, are excluded from the program. Otherwise, though, the offer is made to any defendant with a charge subject to probation, not just those accused of drug offenses, as Getty knows that many burglars and thieves who appear before him are addicts.

Photo by John Sundlof

In most courtrooms, defendants with charges subject to probation eventually plead guilty; under fast-track, pre-trial proceedings are disposed of in a week instead of months of motions and continuances. For defendants who are addicts, a benefit of fast-track is it gets them into treatment quicker, said Bill Gallagher, a public defender assigned to Getty’s courtroom. Addicts who are out on bond for months while their case is pending frequently pick up a new charge during that time, he said. They then face enhanced penalties and almost-certain prison time for committing an offense while on bond.

Fast-track defendants must agree to meet with their probation officers weekly (instead of monthly) and to drop urine weekly. They are not penalized for positive urine drops. The drops help determine who needs treatment, and break through the denial that characterizes substance-abusers.

“If a person drops dirty a couple of times, I can try to awaken them,” Getty said. “I’ll say, ‘Well now, wait a minute, Mr. Jones. You told the probation officer you didn’t have a drug problem–but you dropped dirty the first time, the second time, the third time. That means you continued to use drugs even though you knew I was going to find out. Now that ought to prove to you that you are out of control! And unless you do something about that, you’re going to wind up in the County Jail or in the penitentiary–because it’s just a matter of time before you get arrested on another charge.’ The first person I did that with was a young man, and I saw tears running down his cheeks. I could see that for the first time he had to admit to himself what anyone else who was watching him already knew–that he was an addict. That individual did get into treatment.”

But getting a person to agree to treatment is only part of the challenge. One judge who Robert Grandberry appeared before in 1975 gave him five years’ probation and ordered him into a treatment program, much as Getty would years later. Grandberry participated in the program only briefly though, because “I didn’t take the judge that seriously.” There were no repercussions when he left treatment.

Probationers take Getty seriously, said Sheila Griffin, a probation officer assigned to Getty’s courtroom, because of the specific conditions he sets for them, how frequently he checks on their progress, and the sanctions he imposes when they are delinquent. Typically in Cook County, a probationer who doesn’t report to his officer is brought into court only after two or three months of non-reporting. In Getty’s courtroom, a probationer who doesn’t report one week will be brought before Getty the next. The first time he fails to report, or to drop urine as scheduled, Getty sends him to jail for a week; the second time for two weeks, the third time for four weeks, and so on.

“There are immediate consequences and follow-up,” Griffin said. “Treatment can work. But if you don’t have the judicial follow-up, and the probation officer follow-up, it won’t work.”

About 25 per cent of fast-track defendants never drop dirty, or do so only the first or second time, Getty said. Either they had no drug problem, or they were in the early stages of one and were able to stop using on their own. Another 25 per cent get into treatment voluntarily: either they acknowledge their drug problem from the start, or a string of dirty urines and the prodding of Getty and their probation officer convinces them of the need.

The other 50 per cent violate their probations in one way or another, and wind up visiting the County Jail. Those who are arrested on new charges; however, are sent to prison. A week or two in jail usually convinces the probationer “to get in the swing of things,” the judge said.

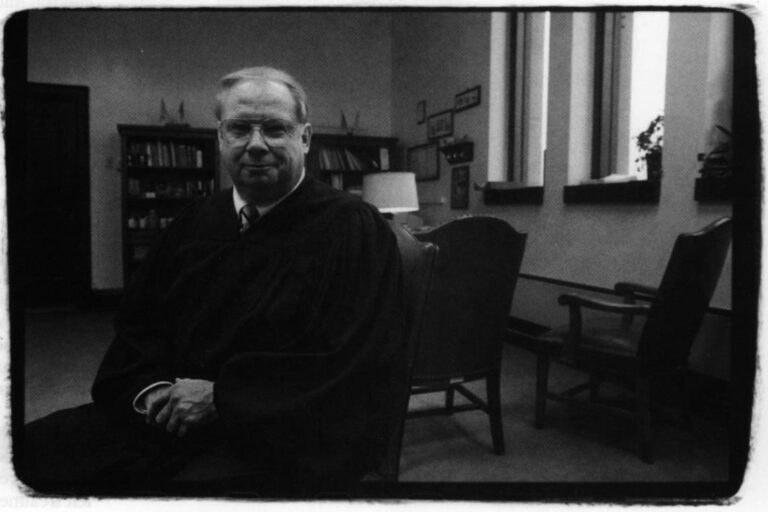

There’s an added benefit to using the Cook County Jail this way: the jail has an acclaimed substance abuse treatment center. Some fast-track probationers agree to stay in the center–occasionally for months–while they wait for treatment slots in the community.

Photo by John Sundlof

Earl Jackson, 35, a heroin and cocaine addict, was put on Getty’s fast-track probation in 1991, after pleading guilty to possession of a stolen motor vehicle. He completed a residential treatment program in 1992, and an outpatient program early in ’93. After a urine drop in June of ’93 tested positive for opiates and cocaine, probation officer Griffin brought him before Getty, who ordered Jackson to bring in proof that he was attending weekly 12-step meetings–as he had agreed to. When Jackson failed to do so in August, Getty ordered him into the jail’s treatment center.

“I just messed up,” Jackson said in the center in September. “I found out my daughter–she’s 15–got pregnant by a 25-year-old man. I wanted to kill him. If I’d have killed him, I would have gone to prison. If I would have called the police on him, my daughter wouldn’t have talked to me anymore. So I did the next best thing–I got high.”

As for Getty throwing him back in jail, Jackson said: “Yeah, I’m pissed off now–but the man’s just doing his job. I got a lot of respect for him. He gives you a chance or two, but if you take advantage of it–nothing else he can do.”

Greg Seawood, 31, a heroin and cocaine addict, has been in the jail’s treatment center since December, 1992, waiting for a bed in a residential center. “When you hear rumor that you’re leaving, you build yourself up on a high that you’re going. Then they snatch the rug out from under you—you’re still here.”

Seawood was grateful that when he got charged with possession in `92, his case happened to be assigned to Getty’s courtroom. “I was rescued—’cause I was killing myself with cocaine and heroin.”

Those who take Getty up on his offer of treatment because they think it’s the easy road are frequently surprised–particularly if they wind up in the jail’s treatment center. “We don’t say, ‘You lost your teddy bear when you were seven,'” said the center’s director, Bobby Matusak. “We tell people they’ve been assholes. They’ve been doing what they want to do when they want to do it, and their way don’t work. People come here and then leave because they can’t take a look at themselves. They feel that doing a bit [a prison sentence] is better than doing treatment.”

For many, the road to successful treatment started in front of Judge Getty. “He’s a remarkable judge,” says Robert Grandberry. “A person might have committed so many crimes, but if those crimes are all related to drugs, he will say this person needs something else besides jail. Another judge will say let’s get rid of him, let’s put him in the [prison] system and write him off. But Judge Getty says no, let’s not write him off–let’s give him the final opportunity to change his life.”

What makes these successes frustrating to Getty is the scarcity of treatment slots. Funding for treatment, in Illinois and nationwide, has not kept pace with demand. Legislators want quick fixes, Getty notes. “They think passing a law that says we’re going to lock people up longer is the answer. The statistics show how foolish that is–it just costs everyone more money to house the people.”

Robert Grandberry notes, “It’s almost impossible for a person to begin to kick the habit when they’re waiting for a bed. …When you’re sentenced to the penitentiary and it’s time for you to go, there’s no wait–they’ll take you right away. But when it’s time for you to go into a treatment center, to really address your problems and begin to make changes–you have to wait.”

©1994 Steve Bogira

Steve Bogira, a writer with The Chicago Reader, is examining felony courts and the disadvantaged.