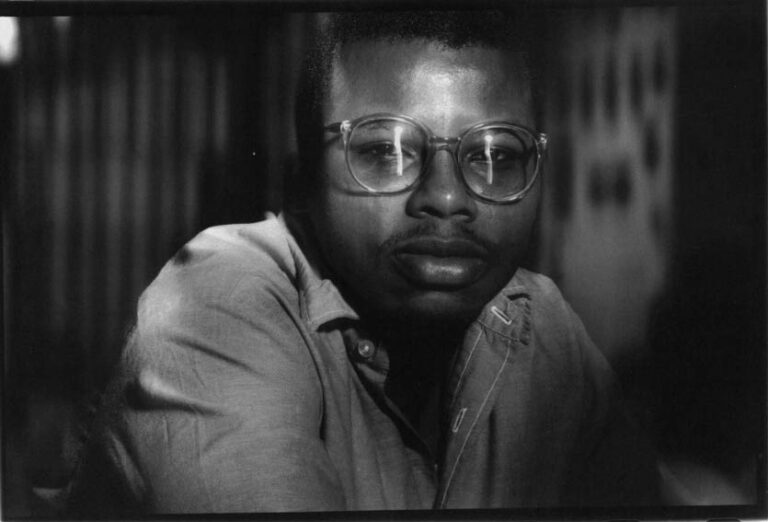

Vincent Boggan is among the few inmates in the Pontiac Correctional Center–a maximum-security prison in Pontiac, Illinois–who avail themselves of the free classes offered. He has already earned an “Associate of Applied Science”–a vocational degree–and now is working on an “Associate in General Studies”–a college-level certificate transferable towards a Bachelor’s degree. The degrees probably won’t ever win him a job, but “they’re doing a lot for me personally, ’cause I feel I’m accomplishing something,” Boggan, 27, said. “If you’re going to be down here, I feel like, school is free–take advantage of it.”

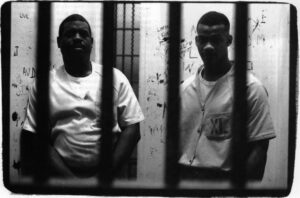

Photo by John Sundlof

If the courses of study were offered and Boggan were up to the task, he could earn several Ph.D.’s in the time he has here. His release date is October 21, 2025–when Boggan will be a half-year shy of his 60th birthday.

Five years ago, Boggan–charged with 17 armed robberies that were committed on Chicago’s south side in a six-week period–was tried on four of them and convicted of all four. He was sentenced to 75 years. (Offenders in Illinois are paroled after they serve half their terms–so the sentence translates to 37 1/2 years of imprisonment.) In the 17 robberies Boggan was charged with, the offender walked into fast-food restaurants, gas stations, and paint stores, pointed a gun at the cashier, and directed him or her to clean out the cash drawer. In none of these robberies did the offender fire a shot or injure anyone.

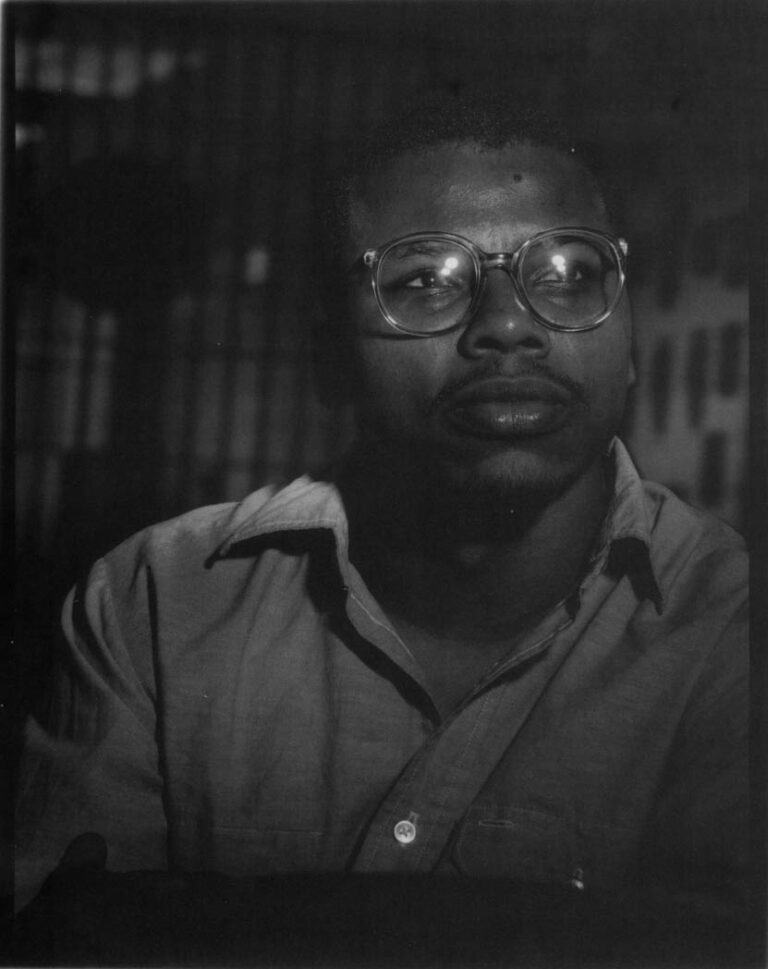

Photo by John Sundlof

Most of the 2,000 inmates in Pontiac are doing time for murder–and many of them have sentences less than half as long as Boggan’s. But Patrick Quinn, the Cook County assistant state’s attorney who prosecuted Boggan in 1989, said Boggan “deserves every second he got and more. He’s a vicious armed robber. It’ll be a good day for the people of Illinois when he expires in his cell.

“This is what happens when you get caught pulling armed robberies–we put you in a cage,” Quinn said. “That’s what criminal law is for–for warehousing evil people. And this is certainly an evil person.”

Boggan, however, would have gotten far fewer years except that he committed a worse crime than holding up cashiers: he held up court.

According to defense attorneys, the judge before whom Boggan appeared, Cook County Circuit Court Judge Robert Boharic, originally offered him a 25-year sentence if Boggan would plead guilty to all 17 robberies. (Boharic declined to be interviewed for this story.) Boggan allowed today that he committed most, but not all, of the robberies with which he was charged. He said he believed the police were using him to “clean up their books,” and that he didn’t want to plead guilty to the robberies he hadn’t committed; so he rejected the offer. Defendants in this country, of course, have a constitutional right to a jury trial. But asserting that right can be risky, as Boggan learned. The state tried him on four of the robberies, juries found him guilty of all four, and Boharic sentenced him to 75 years.

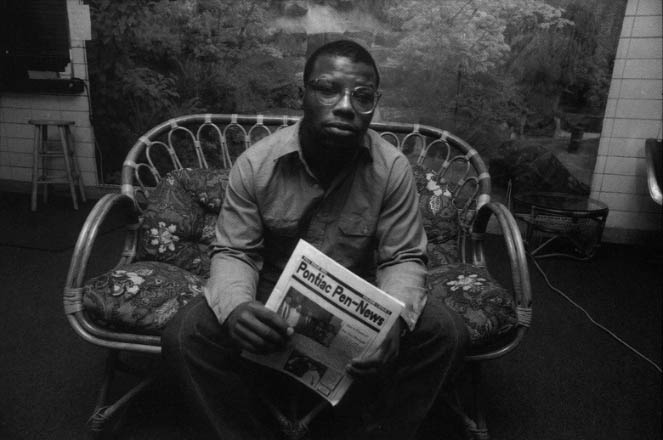

Besides taking classes in Pontiac, Boggan sings in a church choir and is a photographer for the prison’s newspaper. He creates oil paintings in his cell, and runs on the prison’s cross-country team. His discipline record is spotless, according to prison officials. “He’s doing what we want inmates to do–occupying his time productively,” said Illinois Department of Corrections spokesperson Nic Howell.

Like 75 per cent of Pontiac’s inmates, Boggan is black. He grew up on Chicago’s south side. In eighth grade, he was one of two pupils voted “Most Dedicated Student” by his teachers. He struggled academically in high school, but graduated on time. He found work in fast-food restaurants, and then as a janitor. In his first 21 years of life, he was never arrested. But in 1987, his father died. At one of his sentencing hearings, his two sisters and one brother would tell Judge Boharic how their brother seemed to change overnight after their father’s death, from easygoing to ornery. Several months after the death, he was arrested for burglary. Early in 1988, he was picked up for possession of cocaine. He plead guilty to both charges in March of ’88, and was sentenced to 18 months of probation. A few weeks later, police caught him after a high-speed chase following three robberies Boggan pulled in 10 minutes on the south side. Witnesses in these robberies and others of the previous several weeks were brought in for lineups, and Boggan wound up with the 17 charges.

Boggan’s first attorney, Lawrence Goosby, said he looked at the overwhelming evidence in some of the cases against Boggan and advised him to take the 25-year sentence. “I told him, ‘Vincent, they’re going to make you pay [for going to trial]–and the price isn’t going to be worth it,'” Goosby said. But Boggan, who was born-again as a Christian shortly after being jailed for the robberies, “kept talking about a divine power that would resolve this for him.

“I used to ask people who knew him–‘What can I say to convince him [to take the judge’s offer]?'” Goosby said. “‘Cause all I could see was a life going down the tubes that didn’t have to. But the more you would talk to him, the more stubborn he would become.”

After Boggan was convicted the first time, Judge Boharic, who could have given him from 6 to 30 years, gave him 30–five more years for one robbery than he could have gotten for pleading guilty to 17. “Vincent paid the price for tying up the courtroom,” Goosby said. “Someone more sophisticated about the system never would have done this.”

The state prepared to put Boggan on trial for a second robbery. This time, Boggan was represented by a pair of public defenders. These attorneys say Boharic now was offering Boggan another 30-year term in exchange for guilty pleas on the remaining 16 robberies. This sentence would have run concurrently with the sentence already imposed, and would not have increased Boggan’s prison time. The public defenders urged Boggan to take the deal, but Boggan again declined.

At the sentencing hearing following Boggan’s second conviction, Assistant Public Defender Jack Carey reminded Judge Boharic of Boggan’s clean record before his father’s death. The robberies were “an aberration,” Carey said, “and perhaps a response to some sort of personal tragedy that he never had a chance to..come to grips with.”

Illinois’ sentencing law, like that of most states, has a strong presumption towards concurrent sentences for multiple offenses. Judges in Illinois are directed not to impose consecutive sentences unless they deem this necessary “to protect the public from further criminal conduct by the defendant.”

That’s what Boharic found. The judge who had reportedly considered 25 years sufficient before the first trial, and who had offered 30 years before the second, now concluded that this was not nearly enough to protect the public. Calling Boggan “an extremely dangerous human being,” he gave him another 30 years, the second sentence to run consecutive to the first.

And 60 years–or 30 actual years of imprisonment, meaning Boggan would get out of prison at age 52–apparently still wasn’t enough to safeguard the public from Boggan. After a third jury trial and conviction, Boharic tacked on another consecutive sentence, this one for 15 years. “This is a person that needs to be incapacitated for the rest of his adult life,” the judge said for the trial record. After Boggan’s fourth conviction, Boharic added an extended term of 60 years. (Defendants in Illinois are subject to extended terms when convicted of two or more separate felonies in a 10-year period.) But the judge made this sentence concurrent to the two 30-year terms, leaving Boggan’s actual sentence at 75 years.

When a defendant whose guilt seems obvious refuses to plea bargain, most judges get annoyed, said public defender Carey. “From the system’s point of view it’s, ‘Okay, if you really have an issue here, take your trial. If you’re just trying to jam up the works, I’m going to send a message to the other people who are standing in line behind you, that if you take some of my time, I’m going to take some of your time.’ It’s a very practical thing for a system that has too much to deal with. Yeah, there are rewards if you play the game. If you don’t, there are some–disincentives.”

Several years ago, Carey defended another armed robber who had committed a string of hold-ups of fast-food restaurants. This defendant, in his 40s, was a veteran of the courts. He, too, had his case before Boharic, who, Carey said, was offering 18 years in exchange for guilty pleas. The defendant filed complaints against Carey and the judge in an attempt to get his case assigned to another courtroom, and he ultimately succeeded. The new judge gave him nine years. “This guy effectively cut his sentence in half,” Carey said. “He took on the system and won–but he was a little more artful about it. He had more experience.”

The day Boharic sentenced Boggan to his second 30-year term, the judge sentenced another defendant in his courtroom for killing two men–stabbing one of them 21 times, and strangling the other with a telephone cord. Unlike Boggan, this man had a history of violent-crime convictions. This defendant, though, had plead guilty–and got 60 years, the same as Boggan had received at that point for two armed robberies. Boggan ultimately would get 15 years more than the murderer.

Prosecutor Quinn said he never discloses the terms of plea offers. But if Boggan was indeed offered a much shorter sentence than he got, Quinn said, “perhaps he should have seen the light and asked to be rehabilitated instead of demanding trial.”

Boggan “was just crushed by the system,” Carey said. “Here’s a guy who had a period in his life when he certainly was not making good decisions. And that continued when he was making decisions about whether to go to trial or not. But how long do you punish somebody for those really bad choices? And how long do we as a society want to pay for this?”

At today’s rate of $19,000 a year for housing and feeding Boggan, it will cost taxpayers nearly three-quarters of a million dollars to keep him behind bars, if he lives until his release date.

Boggan’s parents both worked, making modest incomes. In 1973, when he was seven, the family moved from a decaying neighborhood near Comiskey Park to Auburn Gresham, a middle-class south-side community. Auburn Gresham was undergoing a metamorphosis when the Boggans bought their house: the census tract into which they moved changed from 96 per cent white in 1970 to 98 per cent black by 1980. The standard of living didn’t decline as precipitously, as it often does in neighborhoods that change overnight from white to black, but decline it did. The unemployment rate leaped from 2 per cent in 1970 to 10 per cent in ’80, and would climb to 15 per cent by ’90. Poverty and crime grew; drugs flowed in; and black boys began departing the area in hearses and paddy wagons.

Vincent’s mother, Velma, a dispatcher at a police station, grew marijuana in the backyard, dried it in the basement, and smoked it in the house–never in front of the kids, but they recognized the aroma. She was driving home from work one autumn afternoon in 1979 when she fell asleep at the wheel. Her car drifted into oncoming traffic, and was demolished by a truck. She was in a coma for a week before she died. Vincent was 13.

Vincent’s father, James, preferred Canadian Club and seltzer water to dope. Sometimes he would send Vincent to the neighborhood liquor store for his half-pints. A proud and protective man, he could be moved to violence by an affront to his wife or kids. Vincent saw him shoot at one neighborhood youth and pistol-whip another for insulting Vincent’s sisters.

In 1985, when Vincent was a high school senior, his father got laid off. James Boggan had house and car payments, and four kids to feed and clothe on an unemployment check. He turned to the surest source for quick money in the neighborhood: he started dealing cocaine.

He made no attempt to hide his occupation from his kids: he dealt right out of the house. He taught Vincent and his other son how to cut and package the dope. Other dealers were selling their coke in rocks, but James Boggan ground his into powder and packaged it distinctively–he wanted his customers to get their $25 worth in each bag they bought from him. “People came from way up north to buy my daddy’s bags,” Vincent said.

While dealing cocaine was acceptable in the Boggan household, using it was not. Vincent’s father “let it be known that that was a no-no,” Vincent said.

James Boggan was a diabetic who had stopped taking his insulin when Vincent was small. That and drinking caught up to him in January of 1987: he had a stroke one night and died, at age 47.

After he died, “I was trying real hard to fill his shoes,” Vincent said.

“He had four ounces of cocaine left in the cash box, and I was feeling, it got to go [be sold]–we got to go on. My sister was saying, ‘Okay–when you get through with that, it’s over.’ I’m like, ‘Is you crazy?’ People were still coming to our back door [to buy the dope]. I said to her, ‘He ain’t showed us how to do all this stuff for nothing.’ I had already justified it to myself.”

Like his father, Vincent wanted to sell a quality product. “I wanted to build my clientele, I wanted people to say.’He got the baddest stuff on the street.’ I’d be mixing it up–I’d take a bump, see if it’s all right. I didn’t know nothing about this stuff, so I’m tooting, trying to figure out what’s right and what ain’t. Next thing I know, I’m making myself little party packs–quarter-bags. It started becoming a pleasure drug.” Snorting lead to smoking; soon, Boggan was smoking up his profits.

At a party one night, a friend who worked at a chicken restaurant talked of a grievance she had with the place. “I should have someone stick me up,” Boggan recalls her saying. She proceeded to detail when she took the restaurant’s weekly receipts to the bank. Boggan offered to oblige. “I was really joking,” he said today. But when the day arrived that the woman had described, Boggan had no money in his pocket and a craving for crack. “And I said, ‘I’m going to go and do this.'”

He met the disgruntled employee at the door of the restaurant as she was about to leave for the bank, pointed the gun at her, and announced the stick-up. She was stunned; she hadn’t been serious. He got $900. Running to his car, he tossed the gun away. “I wasn’t planning on doing no more stick-ups,” he said. Later, though, “It was like, ‘I just made $900 that quick.’ Then it all started.”

Soon Boggan was doing robberies several times a week. He smoked cocaine only for four months, he said, and the robberies occurred during the last two months of that period. He doesn’t completely blame the cocaine for his actions; but the drug had a powerful influence on him, he said. “I was conscious of what I was doing, ain’t no doubt. But I was under the influence every robbery–’cause I stayed under the influence. Only time I wasn’t under the influence was when I drank the high away.”

When he thinks about the robberies now, “I’m like–man–what was I thinking? What was going through my head? That ain’t even rational.”

On April 20, 1988, the law caught up with him. That was the evening he pulled holdups of three businesses in 10 minutes, then led police on a high-speed chase involving 10 to 15 police cars. He raced down residential streets, through alleys, and over sidewalks, bowling over garbage cans, and finally skidded to a stop between several squad cars.

“When I got in that paddy wagon, it was like, ‘What a relief it is,'” Boggan said. “I ain’t want to be locked up. But I had been on an ugly run. Inside, it was, ‘Oh, thank you, God.'”

He considered it a miracle that he hadn’t killed someone or been killed during his “ugly run.” Soon after, some preachers were visiting inmates in the jail where Boggan was being held awaiting trial. “Usually I wouldn’t pay no attention to them. But I wanted to hear what they was saying because it was like–I got myself into something I can’t get out of. And then all kinds of stuff started hitting–like my father’s death. When I got in jail and he ain’t come and got me, that’s when I realized–aw, man–my pop is gone.”

So Boggan soon was born-again as a Christian. Attorney Goosby, noting how Boggan’s faith may have influenced his decision not to plea-bargain, said, “I wish he’d have gotten saved a little later.”

Boggan said today: “I feel I should have been punished, ain’t no doubt. But I feel like the judge had a personal vendetta against me. I believe in punishment if it’s for correction. I feel I learned my lesson the year after I got locked up. Maybe I shouldn’t have gotten out of here that soon–but it don’t take 37 years of my life to correct me from that.

“If I knew then what I know now I would have copped out [plea-bargained] to the 25,” he said. “I should have played the game.”

Had he taken the 25 years, he’d be in a medium-security penitentiary now instead of a maximum-security one. In Illinois, prisoners usually are kept in the maximum-security pens until they’re within 14 years of release. According to that schedule, Boggan will spend another 17 years in a maximum pen.

The chances of getting attacked by another inmate are far higher in the maximum-security pens, prison spokesperson Howell said. There are fewer educational and recreational offerings in the maximums. And while medium-security prisons are rarely on lock-down (during which all inmates are confined to their cells around the clock as a safety or disciplinary measure), Pontiac was on lockdown 115 days last year.

Photo by John Sundlof

In 1991, an Illinois appellate court considered Boggan’s appeal of his sentences. His attorneys pointed out that the four robberies he was convicted of occurred in 16 days. “According to Judge Boharic, in a little over two weeks, the defendant managed to deserve life in prison, even without harming anyone other than financially,” the lawyers argued. “The serious nature of armed robbery would not be deprecated by this court reducing the term of years from 75 to a number more in keeping with the age and background of defendant.” The appellate court noted that the sentence was within statutory limits, and rejected the appeal.

Boggan still has a post-conviction petition pending, in which he once again asks the courts to reconsider his sentence. But he acknowledges that the petition is a long-shot. He tries not to think about how old he’ll probably be before he is released. “I believe that the Lord, in his time, is going to do what he’s going to do,” he said.

In the meantime, “I’m going to try to get myself in a position where I’ll be ready to go–yesterday, if possible,” he said. “I’ve seen too many guys leave up out of here with no skills, no direction–and just come right back, or get killed out there or something, thinking they can do the same thing they was doing when they got locked up. That’s why I’m staying in school. I know that in order to do it right whenever I get out, I have to get some kind of skills while I’m down here. I ain’t planning on giving up.”

@1994 Steve Bogira

Steve Bogira, a writer with The Chicago Reader, is examining felony courts and the disadvantaged.