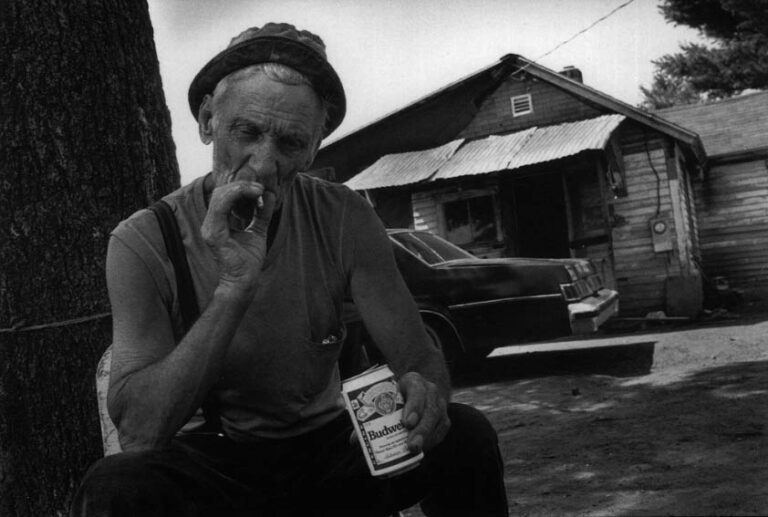

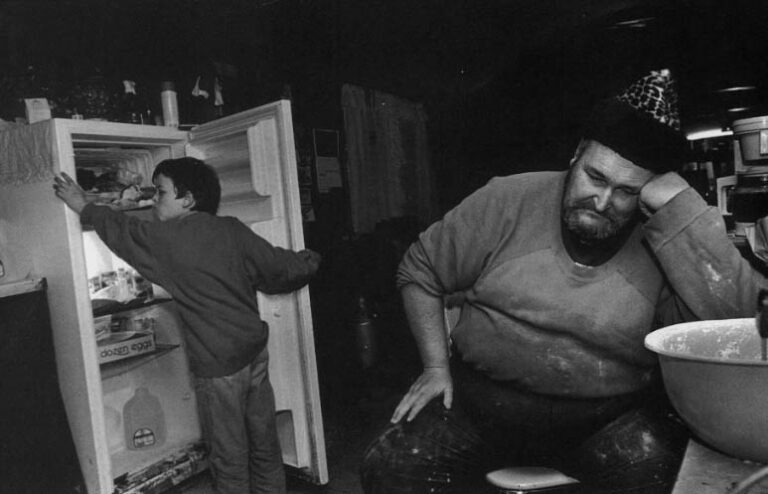

Everett York leans back and rests his massive weight on a worn Lazy Boy recliner that belongs indoors but looks right at home amidst the miscellaneous junk, cars and car parts that litter his trailer’s yard. Close by, his wife, Rena, reclines on the rickety stairs that lead up to the trailer with a gracefulness that belies her size. Everett begins to reminisce about their town’s past.

“Ayuh, there used to be stores, all kinds of stores and you could buy anything you wanted right here in West Athens. Oh, back then it was good. We had two saw mills and a shingle mill, even a cider mill down near where…”

Rena can’t refrain any longer from adding her recollections and bursts in, “I’ll tell you, mister, this was some town! We had two stores and a gas station, plus a church. We even had a hotel right here. I don’t remember it, but I’ve heard people talk plenty about it. And, let me see, there was one, two, three, four! houses right here in a bunch. Grammy Fannie told me that, when she was young, it looked just like a REAL village!”

West Athens is a town that was not meant to be.

Photo courtesy of the Athens Historical Society

In the beginning, there were saw mills. When Central Maine was settled two centuries ago, its rugged hills were covered with millions of acres of virgin forest. One place seemed particularly ideal for the lumbering: a vast amount of timber combined with a good river to power saw mills and transport the cut lumber to market. Early in the nineteenth century, several logging companies discovered the area and set up saw mills down on the Wessarunset River. At first it was called simply, The Mills. Soon, a great many people had emigrated to the settlement and it became known as West Athens, situated as it was only three miles from the town of Athens.

During those prosperous decades, 1830-1880, the lumber companies poured money and jobs into the village. West Athens became quite a backwoods metropolis. The 1870 census showed 1,540 people in the township. By 1970, and today, the village is home to about 150.

The town supported many businesses, including stores, hotels and a dance hall. The companies and citizens built schools and roads, and the town grew to overshadow Athens. Records from that time show that the majority of locally prominent figures such as town selectmen, justices and school board members actually lived in West Athens.

The sole problem was that West Athens was never intended to exist. The timber companies came there for a specific purpose, to obtain low-cost raw materials by using inexpensive and expendable power and labor. The logging industry, mobile by necessity, followed the forests. In those days, logging operations seldom remained for more than a year in one location before it became deforested, or timbered out. West Athens, however, offered a gateway to an immense amount of uncut timber — and so the logging operations stayed for decades, plenty of time for a community to root. The village that emerged was secondary to the business of logging and was to serve workers’ needs for food, housing and entertainment. It was unlike Athens, which had been incorporated a generation before to serve the communal needs of an existing population.

Eventually, the inevitable happened and the area became timbered out. One elderly native of West Athens recalls, “Around here when I was a kid there weren’t no trees. Loggin’ took most. Used to be, a crow flew over here it had to keep goin’ three more miles before it could find so much as a branch to set up on.” The lumber companies abandoned more than the usual rough, thrown-together camp when they left town. Taking with them the jobs that had built West Athens, they crippled the town left behind.

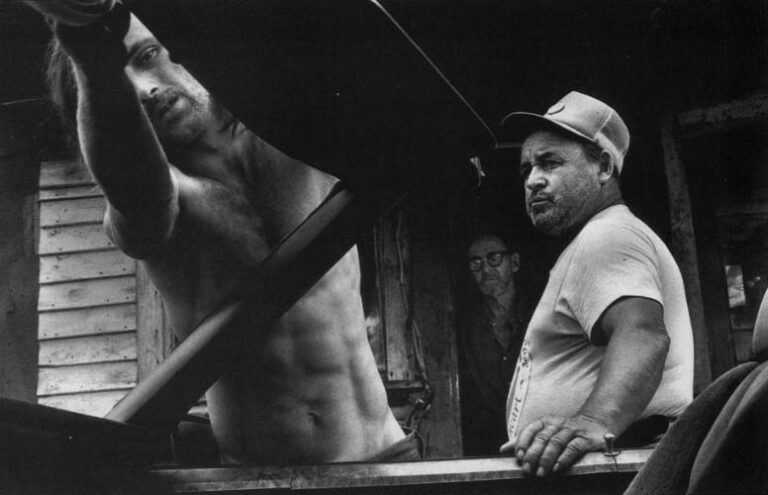

Today the village’s layout is physical evidence of its logging camp roots. The shacks and trailers where the citizens of West Athens now reside are scattered randomly along the rutted dirt roads with no plan, no center, no heart to the community. The wrecks of abandoned saw mills hunker on the banks of the trickle that was once the Wessarunset River; from there, four roads radiate toward the major points of the compass. Originally, the north, east and west roads led to the forests while the south road (the only paved one until just months ago, when the east road to Athens also was paved) led to the railroad in Skowhegan. Thus the routes that most benefited the lumber companies of 150 years ago still determine the societal geography of West Athens in 1994, where there remains no school, church or post office — not so much as a general store.

When the logging companies left, many people went with them. After all, most of those who came to West Athens had come for the most American of purposes: to make money. But there were others who, for a variety of reasons, remained; some because they had put down roots, started farms or businesses and families, others because they could not afford to move on. Workers disabled in the hazardous logging industry and women widowed by it, their children, the elderly — all those most likely to be poor in any population were trapped by circumstance in a town that had lost its economic mainstay.

For whoever remained, prospects were not encouraging. Central Maine’s rocky soil and long, harsh winters do not lend themselves to farming, and there was little else in the way of employment in this isolated region. Fate continued to be unkind to West Athens in the following decades, sending disasters such as fires that destroyed the village’s schools, which were rebuilt, and stores, which were not. A major flood in 1901 destroyed many of the surviving businesses, and wars consumed many of the village’s young men. Eventually, the post office and schools were closed. When the last operating store in West Athens burned to the ground in 1947, residents could no longer buy even the most basic of necessities in their home village.

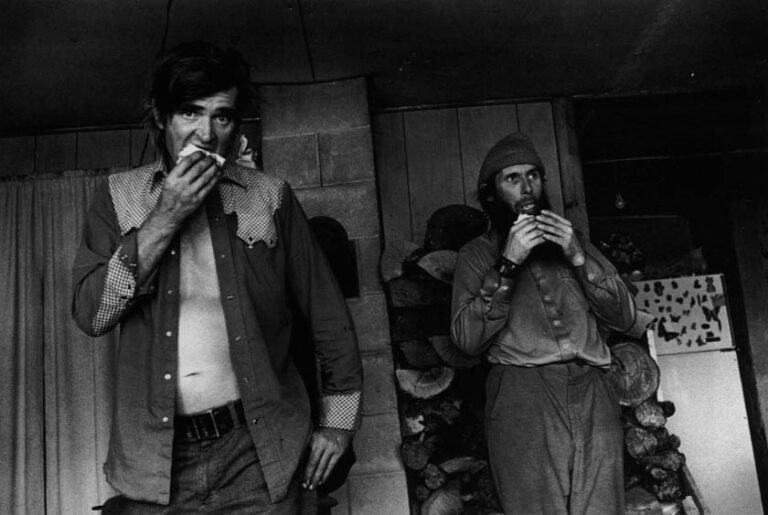

Not that there were many residents left. West Athens shrank from its 1880s peak as an active town to a handful of homesteaders in tarpaper shacks, using pioneer survival tactics well into the twentieth century. They scratched out a living from their gardens and whatever meat they could hunt, made a little money cutting timber by hand from scattered patches left by the logging companies. Johnny Avery, who was born in West Athens in 1926, likes to talk about the old days. “The Great Depression weren’t so great around here — we were so poor already we didn’t notice. You know what lard is? We used to take lard, spread it on a biscuit, leave it out all morning to warm up while we worked since there weren’t no wood or coal for a fire. Then you’d eat it for your dinner and that’s all you’d get for a day. If you had potatoes you ate potato, but then you didn’t get no biscuit. You couldn’t have both.”

He goes on, “We grew near about everything we needed ourselves. Sometimes, we’d be so hungry of a winter we’d want to eat our seed stock but we couldn’t, else we’d starve for sure. That’d be your next year’s seed crop gone, unless somebody give you some.” Which more than likely would have happened; life is not generous to West Athens, but its people take care of each other in this half-forgotten village scorned by outsiders as dirt poor and white trash.

West Athens, once prosperous, is now desperately poor. Those who fled left behind a community where poverty was even more concentrated. Worse yet, the way that West Athens adapted to financial crisis only accelerated its downwardly mobile cycle. In order to survive, residents took any work they could find — usually poorly paid, dangerous or menial jobs no one else would perform. Everett York recalls that his mother would walk miles to pluck chickens or risk her life climbing onto roofs to wash attic windows. This kind of poverty-driven desperation only reinforced the village’s lowly image to those in the outside world.

Rena and Everett York’s successful, prosperous ancestors lived in the same town in a very different era. Talking about a wealthy great-aunt, Rena exclaims “She had MOOLAH! She owned the Kincaid store, a hotel, a livery stable, and let’s see one two, THREE houses — she owned half of West Athens.” She and husband Everett go on to list other relatives and their once-upon-a-time fortunes, their businesses and real estate, with a glee that strikes the contrast between glory past and poverty present. Thoughtfully, Rena concludes, “Yeah, I had relatives with money. But they never give me none.”

Vintage postcard courtesy of the Athens Historical Society

Today, few people in West Athens have regular, identifiable jobs. Most get by doing whatever work they can find or create — hauling garbage, chopping wood, fixing cars, baby-sitting. Their only alternative is to travel outside the community and compete for scarce, menial low-paying jobs. Many depend on government aid checks, food stamps and utility subsidies in order to survive. West Athens has become a rural ghetto, where there are no jobs and little hope or opportunity for a better life. Aaron Corson, whose family has been in West Athens since 1810, summed up the locals’ attitude, stating, “The politicians talk about advancing the economy but I don’t see no one around here getting advanced.”

Its citizens are reluctant to leave, however; isolated from the rest of the world, they have little hope that life would be easier anywhere else. Leaving would mean abandoning the one thing of value they still own: ancestral land, inherited from forebears who had no heirlooms to pass on. People in West Athens, where indoor plumbing is a luxury, make up for their lack of material wealth with a rich sense of belonging to their town and its history, and so they hang on. Every day brings a new struggle to survive, but they enter it with ingenuity and independence, energy and strength.

@1994 Steven Rubin

Steven Rubin, a freelance photographer who works for JB Pictures, is examining rural Maine during his Alicia Patterson year. He is the first Josephine Albright Patterson fellow of the foundation.

The author would like to thank both Marion Hall and the Athens Historical Society for the loan of vintage photos, and Michelle Gienow for her invaluable research efforts.