Photographers enter people’s lives for periods as short as minutes or as long as weeks. Constrained by deadlines and journalism’s compressed time, the assignment ends and we leave. We never stay, we rarely know what becomes of the people we photograph. Editors may permit an anniversary special or the occasional follow-up, but rarely the follow-through.

West Athens is different. With this work I have a personal commitment to return — to accompany this village through time, to follow the children of the children I first photographed years ago. For me, this project is a history. I seek to document the life cycle of this community over real time.

The first time I walked down the dirt road into West Athens in 1982, I could tell I wasn’t wanted. Suspicious, light blue eyes peered out at me from trailer doors and from behind curtains, watching the stranger in their closed community. But with time and persistence, I began to be accepted. Eventually people extended their trust, allowing me to witness more of their lives.

Life there is defined by isolation and unrelenting poverty, yet it is lived with energy and ingenuity, affection and laughter. This is a rural ghetto with few opportunities or escapes, where even menial jobs are scarce and the only reliable sources of income are government benefits. Perennial poverty, outlasting the eternally promised recovery, never changes in West Athens, where indoor plumbing is a luxury.

People don’t leave. There are other places where opportunities are greater, winters less harsh. But who would trade a life with grandparents down the road, cousins just up the hill for the unknown, an unrooted world that just pays a little better?

Twelve years later, West Athens looks frozen in time. The dirt roads, the fallow overgrown fields, and the faces that live in these sagging, rundown shacks appear to be straight from Depression archives. Yet, every time I appear, people relate the changes since I was last up: Gregory got a haircut, cousin Lori rearranged the furniture, Sonny’s pig is big enough for slaughter now, and the Averys re-wallpapered.

There are universal passages: old timers die, and others age prematurely to replace them. Children grow up quickly, put down their toys, and have children of their own. The cycle of life continues.

©1995 Steven Rubin

Steven Rubin is a freelance photographer, now based in Baltimore. He has been examining rural poverty in Maine for the foundation.

Husband and wife.

Clara found Jesus, got fed up with Elery's drinking, moved back in with her mother and got a divorce. He died a few years ago of cancer.

The Corson family has been replenished by its newest member, Wendy's son, Christopher. Everybody calls him Bubba. Families are smaller today. Wendy doesn't think about having more children, as one stretches her welfare check.

Gregory gives his cousin Lori, a rose. They say wood warms you three times - when you cut it, when you split it and when you burn it. But nothing said about the sparks that fly when you sit on wood with a person to whom you are attracted.

Gregory gives his cousin Lori, a rose. They say wood warms you three times - when you cut it, when you split it and when you burn it. But nothing said about the sparks that fly when you sit on wood with a person to whom you are attracted.

These days Lori always looks tired. She works the graveyard shift at an old folks home in a nearby town. The job pays only $5.00 an hour before taxes, even though she's a long-term employee. Sometimes, just to make ends meet, she also works a part time job at a wood products company packing toothpicks or popsicle sticks.

Currently, Lori shares a house with Gregory and her son JD. The father of her child is wanted by the authorities and fled the state of Maine p; one of the few from the town to leave. She married Jay who decided to divorce her, but hangs around anyway, knowing that Lori still loves him. She and Gregory have remained close through the years. He brings in food stamps, which helps with the food bills and looks after the house and JD. Today the only sparks flying between Lori and Gregory are from their squabbles and arguments.

This photograph represents just a small part of the Corson family, gathered for a moment, pausing from its celebration of July 4th to pose. There's Grandma Rosie Corson, grand dame of the town and loved by all, with two of her eleven children: Aron standing solidly behind her and Elery by her side. Elery is beside his wife Clara, and surrounded by three of their five children: Jeff, Raymond, and Wendy, they baby of the family. Clara's father, Alton Jones stands at her side, supported by his grandson's hand.

With no children of her own, Laura Ann holds a friend's newborn as her nephew Justin ; her brother Harley's boy ; looks on. She moved out of her parent's place and lives with a woman friend. It's a two minute walk away. Laura Ann dropped out of high school. Over the years she has worked a couple of jobs ; construction on the town of Athens' new garage, busing table at a nearby ski area ; but usually temporary or seasonal work, never will paid. A few years back she enrolled in a program to get her GED, but that didn't last.

Deeny is dancing with cousin Kelvin's wife at a relative's wedding. Deeny has had few if any girlfriends, as there are few available women around. He seemed to embody all of his family's hopes when he graduated from high school a few years back, the only member of his family ever to do so. he studied mechanics, and then learned he suffers from night blindness and degenerative tunnel vision p; making a driver's license and employment useless dreams. Unemployed, Deeny still stays at his folks' place and rides around on his bicycle year round.

Roger is waiting for his relative to get ready for the family portrait.

Roger is sitting in his truck with his dog Bo-Bo. He dropped out of high school due to boredom. Unfortunately, life since hasn't been that different p; twice a week he'll haul relatives' garbage to the dump for a little spending money. Steady jobs are hard to find. He still stays at home, and spends most of his time hanging around or fixing up junk cars that he runs into the ground in the woods, smashing through the wilderness, running over the biggest trees the car can handle. Or he spins his wheels on the town's few paved roads until neighboring relative get so irate they call the cops.

Sanford and wife Phyllis are dressed in their Sunday best. Everybody calls her Sugar. Harley is to her left. He is named after the motorcycle. Going clockwise is brother Roger, followed by Deeny, and Laura Ann, who's named after her great-grandmother.

Debbie is pictured with her tow children from her marriage to Speedy. She and Speedy used to work sewing shoes at home, piece work for one of Maine's cottage industries. It was tiresome and debilitating work. Nothing quaint about it.

Debbie and Speedy got divorced when she moved across the road to live with Wilson Foss. Her hands are plagued by tendonitis and she no longer sews shoes. Her two younger children are Adam and Angie. She often complains of having to raise children all over again.

Bruce is outside his father, Speedy's trailer. His parents divorce, his mother moved across the road and had two children with another man. Her son, Adam, Bruce's half-brother, climbs on top. Bruce is skipping school more frequently and says he'd rather tinker with cars.

Harley is shown on the day his father gave him permission to drink alcohol for the first time. A number of times since, he's lost his driver's license for DWI, like his father. He and a girl Becky, who lived down Valley Road, had a child together. For a time they were living in the back of their pickup, parking it outside Harley's parents' place. Later , they bought a used mobile home. These days, Harley works cutting trees, the same job that disabled his father. Becky has just learned she's pregnant again.

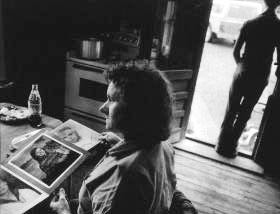

She looks after her daughter Laura Ann's school pictures. She shakers her head in disbelief not quite believing all her kids have grown. Her house is a locus of activity with people coming in and out, wearing out the door's hinges. It's hard to keep the house clean, she often says.

In 1982, Rena and Everett York were the poorest in town. They lived on borrowed land, food stamps and Everett's small disability check. Rena has three living children and lost two. She and Everett go everywhere together. In a town where physical affection is restricted to the adoration of children, they are about the only couple who openly show their love for one another.

More than a decade later, Rena and Everett's two daughters moved away. They each married and have a child of their own. Son Jimmy stays at home, and spends his time with greasy motors or with his girlfriend, Mare. Still the poorest of the poor, Rena and Everett now live on a different parcel of land borrowed from yet someone else.