Former U.S. Trade Representative William Brock and John McDonnell, the chairman of McDonnell Douglas Corp., were talking at a business conference in southern California about two years ago when the conversation turned to the company’s future.

McDonnell Douglas, a $17 billion-a-year enterprise, was in trouble. True, it was the nation’s largest military contractor, making jet fighters, attack helicopters, and gigantic transport aircraft like the C-17. But with the Cold War winding down, the U.S. military budget was sure to be cut, reducing government purchases from McDonnell Douglas. In addition, the company’s management was in chaos, and inefficiency seemed to rule the factory floor.

Particularly worrying for John McDonnell was the competition his commercial aircraft division faced from Boeing and Europe’s Airbus Industrie. He was hoping that renewed sales of civilian jetliners could make tip for the lost military business. But did the United States have the investment funds and the workers with less demanding salary requirements McDonnell thought were necessary to revive the commercial sector?

As McDonnell and Brock continued talking, it became clear they agreed American companies had to look abroad more often if they were to remain strong. “He was discussing the need to look at the world in a larger fashion,” Brock recalls. “We did a verbal scan of the world. I suggested… that one of the countries he should look to for participation in a global effort was Taiwan.”

Brock had become acquainted with the leaders of the Taiwanese government while serving as Ronald Reagan’s trade representative, and after leaving office, he set up his own consulting firm, The Brock Group, which represented the Taiwanese in Washington. Brock describes himself as a “fan” of the Taiwanese – in particular, their risk-taking, entrepreneurial spirits, and basic competitive instincts. These skills, put to use in exporting to the world marketplace, helped the Taiwanese amass ail extraordinary, $82 billion in foreign exchange reserves by early 1992.

The discussions between McDonnell and Brock continued as he was formally hired as an adviser to the 52-year-old bearded son of the aerospace company’s founder. Meanwhile, McDonnell Douglas officials, who had looked unsuccessfully for U.S. investors to shore up their company, were contacted by Taiwanese interested in developing their own aerospace industry. Aided by Brock’s ties with the Taiwanese government, McDonnell Douglas put together an agreement in late 1991 to discuss a $2 billion purchase by private Taiwanese and government investors of up to 40 percent of the company’s commercial division.

Under the tentative arrangement, Taiwanese workers would have built the wings and other parts for a new McDonnell Douglas jetliner, while the U.S. company kept control over design, assembly and flight-testing. The talks about the unprecedented deal recently dissolved over the size of Taiwan’s financial contribution, but they epitomized a dramatic transformation of the U.S. economy whereby foreign capital and managers now play a major role. Critics of the trend say it represents the sale of strategic national assets, with corresponding losses of good jobs and potentially, technological leadership.

Brock does not appear worried. For him, the proposed Taiwan/McDonnell Douglas arrangement was the inevitable outgrowth of international economic changes in which borders and national identities are much less important. It was also the logical consequence of the policies he promoted when he headed up the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), the White House trade policy and negotiating arm.

Brock came to USTR in 1981 as a moderately conservative Republican who was wary of government involvement in the private sector. His family’s business, the Brock Candy Co. of Chattanooga, Tenn., which had funded his political career as a member of the House of Representatives and Senate, was a closely-held concern with no union representatives. When it came to international trade questions, Brock was pragmatic, backing, controls on imports of textiles and other products made in his district while supporting legislation designed to continue the liberalization of worldwide trade.

When Reagan won in 1980, Brock, who had been Republican Party chairman for the past four years, took the USTR post as a reward for his role in the victory. Immediately, he was confronted with demands from the auto industry and Congress for controls on imports from Japan. About 300,000 auto workers, 40 percent of the industry’s work force, had been laid off the year before, and Japanese imports, which were running close to 2 million units annually, were being blamed for the slump.

The car issue sharply divided the members of Reagan’s Cabinet. Several were crusaders for free Market ideals, including the President’s zealous budget director, David Stockman, who wrote in his memoirs that the import limits were a “preposterous idea” and “philosophically inimical to what I thought we stood for.”

Brock says the restraints “went against my instincts,” but he supported them, believing that if the Administration failed to move, overly strict quotas would be imposed by legislation. “The Congress was going crazy,” he says.

“We had to keep from falling into the abyss, with a major draconian action.”

Reagan, like Brock, saw the political need for a deal, and decided in favor of a temporary ceiling on import levels.

Also discussed, but riot accepted by the Administration was a more elaborate arrangement involving a formal commitment by the auto companies to improve fuel efficiency, restructure management, control wages and make other improvements in exchange for the Japanese car quotas.

Such a complex deal would have been extremely difficult to enforce, but in any event, Brock indicates he wouldn’t have strongly advocated that course. “I’m not much of a believer in those things,” he says.

In fact, the car companies did promise the Administration informally to do what was necessary to become more competitive. Sales began to climb again in 1983 and 1984, but Brock was angered when the companies’ executives were given enormous bonuses. He thought it was an “outrageous and stupid” move, setting the wrong example for an industry still in need of fundamental changes, and he opposed the extension of the Japanese import quotas. But it was 1984, ail election year. That fall Brock felt compelled to back relief from imports for another major industry, steel, again without a formal promise from the companies for restructuring.

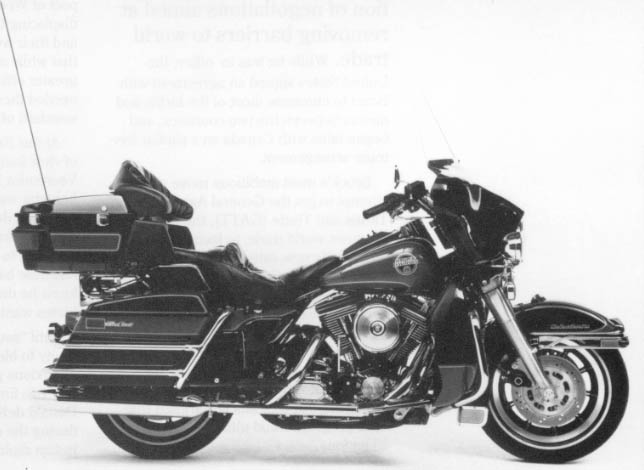

The year before, Brock had also supported the imposition of high tariffs on motorcycle imports to protect Harley Davidson Co., which was suffering from competition with Honda and other Japanese manufacturers. Brock’s general counsel, Donald deKieffer, a weekend motorbiker, shed his suit and tie for leather gear and tested one the company’s “hogs” at its York, Pa. plant. He assured Brock that the firm had a good plan for renewing itself (that, story has a happy ending: today, after successfully focusing its marketing campaigns on upscale buyers, and improving the quality of its machines. Harley dominates the “ super heavyweight” motorcycle market, and the import controls have been lifted).

But Brock believes his biggest achievements at USTR lay not in the political management of demands for protection, but in the initiation of negotiations aimed at removing barriers to world trade. While he was in office, the United States signed an agreement with Israel to eliminate most of the tariffs and quotas between the two countries, and began talks with Canada on a similar free trade arrangement.

Brock’s most ambitious move was an attempt to get the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the body that oversees world trade, to focus on dismantling whole new categories of trade barriers. Meeting in Geneva in November 1982, senior officials from GATT member countries discussed such problems as national restrictions on foreign insurance and engineering firms, and the growing trade in counterfeit goods. It was air agenda that reflected American economic strengths, but U.S. officials argued that their program could ultimately benefit all nations.

Brock got many of his ideas for the new trade negotiations from a Hungarian born staff economist at USTR, Geza Feketekuty, who had been gathering information on emerging trade problem for several years. Not wishing to “micromanage” every aspect of his agency’s often arcane activities, Brock preferred to engage in philosophical conversations with Feketekuty about the direction of world commerce and the “system” necessary to run it.

Feketekuty praises Brock as a kind of quiet “revolutionary” who wanted to “ shake up” people’s conventional ideas about what trade policy was. Instead of viewing trade as simply the exchange of goods, Brock and Feketekuty sought to extend the definition of commercial activity to the provision of services. One example Feketekuty used was Pan American Airway’s problem convincing some countries that it should be allowed to carry their international mail on its established flights, rather than always transferring it to national airlines.

These new concepts of trade freedom provoked the opposition of many countries, particularly the poorer members of the GATT. India, whose airlines, banking and insurance industries were government-run, was concerned about the prospect of Western companies coming in and displacing these comfortable monopolies and their workers. Indian officials argued that while openness might provide for greater efficiency, impoverished India needed these industries to help raise its standard of living.

At the 1982 Geneva meeting, this point of view found a forceful advocate in Veerendra Patil, an Indian Cabinet member who was the senior member of his country’s delegation. Patil, who switched that year from heading up the ministry of shipping to leading the ministry of labor, had little background in trade policy, but knew he didn’t like what the United States wanted in the GATT.

Patil “sought every conceivable opportunity to block everything … in the most obnoxious possible way,” recalls Brock. The two finally had a showdown, and Donald deKieffer, who was in the room during the closed-door session, says the Indian diplomat was spouting “propagandistic fluff” about how the United States and the industrialized world were oppressing poor countries like India.

Brock, who thought it had been agreed to keep such time-wasting rhetoric out of private meetings, became very angry, but kept it to himself until Patil finished. Then, Brock says, “I put the wood to him in no uncertain terms… I suggested that hell would be dappled with little icebergs before India got anything out of the United States if they continued to act that way.”

“He said I couldn’t say that, and I said, at eight o’clock in the morning (tomorrow) you’ll find out, if your position remains the same.”

India did need the cooperation of the United States in other matters, and Brock says relations between the American and Indian delegations were “less contentious the next day.”

But the Geneva meeting produced little, because several other countries were just its opposed as India was to some of the American ideas. Brock says it was a “success only in that it did not fail.” It took four more years of preparations before a new round of global trade negotiations were kicked off. They are still going oil today, more than a year after their scheduled completion. If an agreement is eventually produced, it is certain to be much less than what was originally sought by Brock.

Nevertheless, Brock thinks that the pursuit of a freer world trading system is the only sensible policy for the United States to follow. “Why don’t people accept this as a strategic plan?” he asks, showing some annoyance, when told that critics faulted the Reagan Administration for having no programs to aid specific industries. Providing financial backing for important companies and managing trade in designated goods is no strategy, he says, only a tactic.

In keeping with his beliefs, the Brock Group does not take on clients that are seeking protection from imports because they’ve failed to be competitive, Brock asserts. That’s not an unprofitable principle, because with the rapid internationalization of business there are always companies that need assistance breaking into foreign markets.

Brock’s vow also doesn’t prohibit activities like advising McDonnell Douglas oil its proposed link-up with Taiwan. But the Taiwan arrangement does bring Brock into an ambiguous position as far as his views on government involvement in business is concerned.

The Taiwanese side of the venture is an instructive example of how many governments around the world are nurturing industries they believe vital to their countries’ economic future. Taiwan Aerospace Corp. was founded last year after the government recruited Taiwanese engineers and scientists trained in the United States. Cash from wealthy Taiwanese firms, plus a generous infusion of government funds, were brought together to bankroll the aerospace company.

“The Republic of China (Taiwan) has a strategic plan, and part of their strategic plan is to aggressively enter the aerospace business,” said Robert Hood, chairman of McDonnell Douglas’s commercial aircraft division, at a Senate hearing.

“I’m not sure we have a strategic plan to stay in,” replied Sen. Jeff Bingaman (D-N.M.), noting that the U.S. government isn’t willing to directly subsidize McDonnell – or take action against its chief competitor, the government-supported European Airbus.

The Taiwanese aerospace initiative is something that in the United States would be seen as an assault on tree market principles, and would appear to violate Brock’s instincts (although the U.S. government has indirectly subsidized McDonnell and other defense industry companies for years through massive spending on military research and development, and support of space exploration). But Brock says that the Taiwanese were determined that the arrangement with McDonnell Douglas operated on a profit basis.

One undeniable result of the proposed deal would have been a loss of American jobs, since McDonnell Douglas planned to transfer more than half of the production operations for the new jetliner to Taiwan. Also certain to disappear were some U.S. subcontracting firms that currently provide parts and labor for the company’s operations here.

Brock, who served as Reagan’s secretary of labor after his term at USTR, defends such ventures as the Taiwanese link-up as the best way to avoid having McDonnell Douglas exit the commercial aircraft business altogether.

“What I want is growth here, jobs here, creativity here,” Brock says, hitting his desk top for emphasis. “If I can do that by forming alliances with people in other countries, and the alternative is to have a failed company, I don’t think that’s a serious choice.”

Besides, he argues, these cross-border alliances are becoming commonplace. American companies are huge investors around the world, and their health has only been enhanced by the freedom they enjoy to enter other markets. It would be “hypocritical,” he says, to think we can keep our own market all-American. And if some countries aren’t as open as we, are, that’s just all the more reason to push harder in the GAIT and other forums.

“Global means global,” he asserts. “We’re going to find it increasingly difficult to fund things oil a national basis.”

©1992 Steven J. Dryden

Steven J. Dryden, a writer in Bethesda, Maryland, is examining the role of the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative in world trade issues.