In exile, now, and far away, it is still easy to recall clearly the joy of sitting alone beside a waterhole, silently listening to the sounds of wild game. Waiting patiently, I anticipated and watched the movements of buck, of lion, of elephant or giraffe, or so many other animals. All came down to drink, each practicing a caution long learned…I have yet to find a land so full of warmth and so rich in beauty as my homeland.– No Neutral Ground, by Joel Carlson

Year after year, thousands of South African exiles follow the rise and fall of domestic South African resistance and wonder when it will all end. For some, exile has been a personal liberation, freeing them from the trauma and limitations of apartheid. For others, exile has been a kind of incarceration. No matter where South African exiles go they cannot escape their own homesickness. They meet at conferences or dinners, they exchange some words in Afrikaans or Zulu or Xhosa and laugh at their shared secrets–their arcane mother tongues and the unspoken sadness of exile.

As the struggle against apartheid drags on, the South African diaspora has grown, scattering political exiles from Leningrad to London, from the jungle of Angola to hills of Jerusalem, from Dar es Salaam to New York. Altogether there are about 20,000 South Africans in political exile, a community made up of students, guerrillas, and liberation bureaucrats. Some are private individuals who just couldn’t tolerate South Africa anymore. One is Joel Carlson, a lawyer who left South Africa in 1971 after his house was bombed, gunshots were fired into his office, his passport was seized, and his family subjected to a series of poison pen letters and ominous, late night telephone calls.

In contrast to South African whites who flee in fear of majority rule, these South Africans, black and white, eagerly await a change to majority rule and the chance to return home. By circumstance or design, they have been driven into political exile over the past three decades.

Many political exiles have grown old and gray; some now realize they may never return. Some sink into despair, like Nat Nakasa, a talented young black journalist who flung himself from a seventh floor window in New York in 1964. Recently, a student at the African National Congress school in Tanzania wrote to a friend, complaining about living conditions and isolation from his family.

One story that is repeated by exiles is told of a homesick South African political exile who goes to the South African embassy in London and says he wants to renounce his political beliefs and return to his beloved country. The South African embassy official says that in order to be forgiven for his political activity, the exile must spy on students at Oxford University. In the process of photographing a student’s private correspondence, the exile is caught and tried by an ad hoc court of South African students at Oxford. Some want to kill the hapless exile and bury him in the woods. But in the end, they decide to punish him by spreading word of his treachery and making sure that the door of every South African in England is closed to him. The South African embassy fails to make good on its promise to repatriate the homesick exile. Spurned by his fellow countrymen, he breaks down and ends up in an asylum. The story may be apocryphal, but it is one that resonates for many exiles.

Others adapt, like ANC national executive committee member Thabo Mbeki. The contours of his paunch have grown rounder, his accent is marked with British cadences, his pipe is filled with sweet smelling tobacco. To all who meet him, he is the consummate diplomat, at home abroad. Recently when Mbeki’s father was released from prison in South Africa, Mbeki the younger seemed happy just to be able to speak to his father on the phone and see his photograph in the newspapers.

Many arrived in exile by chance. On March 21, 1960, the eve of the first state of emergency in South Africa, 17-year-old Frene Ginwala received a telephone call from one of the top leaders of the African National Congress. He suggested she pay a visit to her parents. Since her parents were then in Mozambique, Frene decided this wasn’t just a piece of personal advice. She figured the ANC man meant that she should go on a mission outside the country. So she packed up and left South Africa.

That mission never ended. Days later, the ANC was banned and supporters like Frene Ginwala were left stranded in exile. A quarter of a century later, Ginwala sat in the London ANC office, brushed back her graying hair and recalled that fateful phone call. “I assume that meant I should leave the country. I don’t know. I never saw Walter again,” Ginwala said, referring to Walter Sisulu, the man who phoned her and who today is serving a life sentence in Cape Town’s Pollsmoor Prison along with Nelson Mandela.

In the 1950s, Ruth Mompati was the secretary at the Johannesburg law offices of Oliver Tambo and Nelson Mandela, the two hottest young black lawyers and political leaders in South Africa. But then life took an unexpected turn. In 1962, with Mandela in hiding and Tambo setting up the ANC in exile, Mompati slipped out of South Africa into neighboring Bechuanaland (now Botswana) for what was supposed to be a mission of a few months. While she was outside South Africa, the South African police arrested all the top ANC leaders left inside the country in a raid on ANC headquarters in the Rivonia suburb of Johannesburg. The organization decided it was too risky for her to return.

“It was a difficult decision,” says Mompati, who had left behind two infant children. She wouldn’t see either of her children for more than a decade. When she did, she says, “they were strangers.” She saw one at age 16; one at age twelve and a half. Mompati still pictured small children in her mind. “I wasn’t expecting these big tall men. That’s when I first felt the shock and horror that I had missed the childhood of my children forever.”

Today Mompati is one of two women on the ANC national executive committee. At the headquarters of the ANC mission in exile, an office in the dilapidated Zambian capital of Lusaka, a thousand miles away from Johannesburg, the 62 year-old Mompati keeps a faded photo of a young Tambo with a partially obscured image of Mandela in the lower right hand corner of the frame.

In addition to missing friends and family, many exiles worry about abandoning their comrades in the struggle against apartheid. Many remain as devoted in exile as they were before leaving. They are sensitive to those who say they are not doing enough.

One of Mompati’s colleagues in Lusaka is Joe Slovo, a white South African who was for two decades the chief of staff of the ANC military wing and is now general secretary of the South African Communist Party. One day Slovo sat down to a lunch of chicken in a basket with french fries at the Ridgeway Hotel in Lusaka, and headquarters of South Africa’s leading liberation movement, the African National Congress. Opening up the Zambian Times, Slovo, a communist lawyer and then chief of staff of the ANC military wing, spied an item about South African exiles. The author of the article complained that South African exiles weren’t doing enough to bring liberation to South Africa. All they did, the article griped, was sit around the Ridgeway hotel and eat chicken in a basket. “I nearly choked on my food,” Slovo recalls.

Guilt about leaving their friends and colleagues pains many exiles. Denis Goldberg, a white engineer, made a deal with the government after 22 years in Pretoria Central Prison, where he was serving a life sentence for treason. Goldberg agreed to leave the country and renounce violence if his sentence were commuted. “Twenty two years–7,904 days–for me was enough. I needed to be active again,” he says sitting in the ANC office in London. “When I first came out, I didn’t know how to use the telephone correctly. I had never seen television. It used to take me an hour to dress. Did I wear gray or brown or black socks? Choice! God, it’s rich. For years I never had to turn on a light, or open a door for myself.”

At first the ANC viewed him with suspicion, then slowly gave him tasks within the organization, ranging from speaking at the United Nations to manning the London office. A British student walks in and inquires about buying ANC banners, T-shirts, baseball caps and coffee mugs for an anti-apartheid fund raiser. Unaware that he is speaking to a man who spent more than two decades in Jail for making explosives for sabotage attacks, the British student treats the prominent political prisoner like a retail store clerk. The 54-year-old Goldberg makes a pitch for a Swatch watch with an ANC insignia on it. “Just 24 pounds and a one year guarantee,” Goldberg tells the student. “There’s a 20% discount to antiapartheid groups.” Upon reflection, the student sticks to the T-shirts and coffee mugs.

Goldberg smiles wryly at his transition from political prisoner to retail merchant. But he doesn’t seem to mind. He is happy to sell a few flowers to promote the cause. “I’m doing something useful. Let’s not knock it. These students carry our symbols into the streets of Britain and raise money.” Goldberg sold about 100,000 pounds of ANC knickknacks last year.

Still, his guilt about leaving others behind serving life sentences ate away at him. Then he went to Vancouver to give a speech and a young Indian woman came up to him afterwards and threw her arms around his neck. She said she had been to visit a lifetime prisoner in South Africa and he had told her that those left behind understood his decision and hoped Goldberg would stay involved in exile. “Sending that message through a young Canadian was like throwing a bottle in the sea,” Goldberg says as tears well up in his eyes. “And to say that while they remain in prison, that’s comradeship.”

Exiled architect Arthur Goldreich, once an associate of Goldberg on the logistics committee for the 1961-63 ANC sabotage campaign, was worried about how Goldberg would greet him in exile. While Goldberg was languishing in prison, Goldreich, who escaped from jail before his trial by bribing a guard, was living in a comfortable house in Herzylia on Israel’s Mediterranean coast. To Goldreich’s surprise and relief, Goldberg clutched his arm as though trying to comfort Goldreich. “We were right! We were right!” Goldberg exclaimed about their decision to wage an armed struggle against the South African government. “Our timing was wrong.”

It is difficult to imagine two men so different. Goldreich doesn’t get teary-eyed about comradeship. Nor has he built his life in exile around other South African exiles. Goldreich moved to Israel where he is a successful architect and teaches at Hebrew University. Although active in anti-apartheid groups in Israel, he is well-adapted and urbane. He gets impatient with the insular world other South African exiles inhabit, a world of refugees and liberation technocrats. “They do the same thing every day. They talk the same way. They talk to people who talk the same way they do. It would drive me mad.” At a conference in Finland, he asked Goldberg to go for a walk in the forest. Goldberg looked surprised. “They don’t go to walk in the forest,” Goldreich says.

To be sure, Goldreich hasn’t forgotten his ANC colleagues. Remembering Sisulu, Goldreich says “Walter’s smile was like a zipper and he had sharp eyes. When he laughed his whole body would respond. When I think that he is 75, it’s just devastating.” Goldreich, once believed to be the arch-conspirator in the ANC sabotage campaign, sits in a Jerusalem restaurant drawing arch upon overlapping arch on a paper napkin until they form a dark ribbed tunnel of arches. Asked if he would return to South Africa with a majority rule government, he says, “God, yes, in a moment. I miss the big sky, the feel, the texture.”

Some South Africans seem to run as far as possible from the big sky of southern Africa. When I visited the office of the Anglican church in Birmingham, England, the only clue to the Rev. Barney Pityana’s former life was the photograph of Stephen Biko on the wall above his desk. Biko, who died after being beaten in a cell in South Africa, had led and inspired the Black Consciousness movement. Pityana had been one of Biko’s top lieutenants. He had delivered impassioned political speeches, saying in 1971 that “we want a revolution–a revolution which brings to an end our weakness, so that we are never again exploited, oppressed or humiliated.”

The Anglican church in Birmingham was a far cry from the South African revolution. Instead of preaching Black Consciousness, the Rev. Pityana was ministering to a group of white-haired English matrons.

“The photograph is an important point of contact. Another of Winnie Mandela often hangs below that one,” Pityana said when I saw him, 8,000 miles from home. “I’m not a deeply emotional chap. But I feel very, very connected to South Africa. I celebrate and rejoice and get excited about what other people are doing.”

Pityana, who has moved to Geneva to work for the World Council of Churches, said he never regrets leaving in 1978. For years, he had been prohibited from attending meetings or speaking in public. He was in and out of detention. Biko was dead. Their organizations were all outlawed. “I just felt I wanted to leave. I felt there was nothing more I could do. Emotionally I didn’t feel I could cope. And one selfish reason was I wanted to be with my family more.”

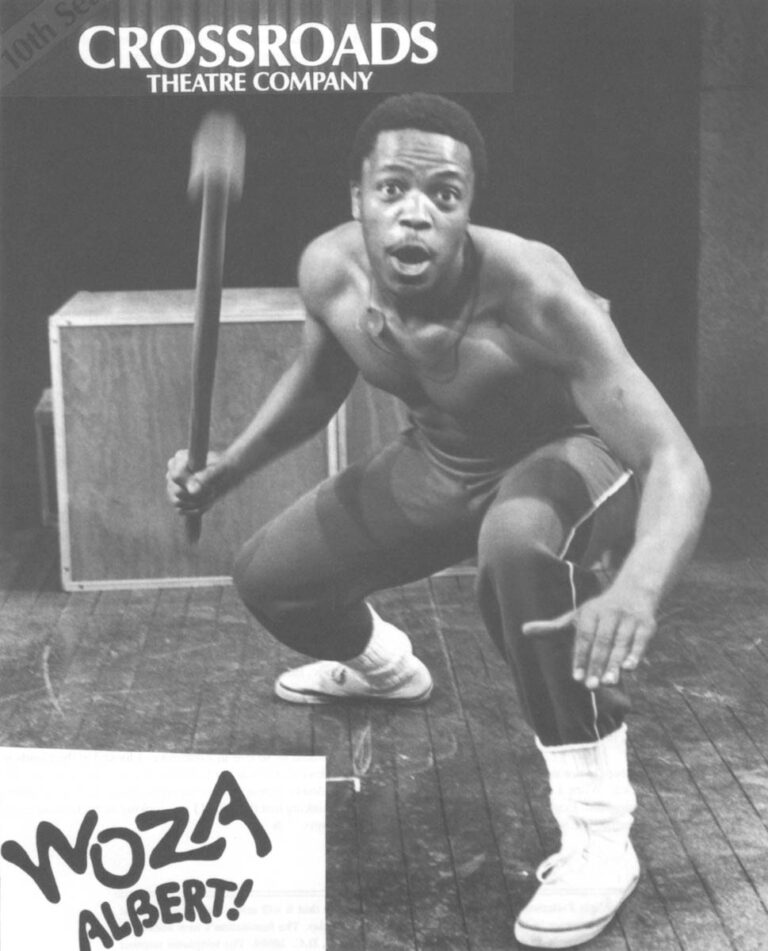

Perhaps it is easier to be in Birmingham, England or by the lake of Geneva or in the busy streets of New York’s Greenwich Village where Fana Kekana makes his home. An actor in South Africa in the mid 1970s, Kekana came to the U.S. to perform a highly political play called Survival, which was about a prison but also suggested that all South Africa was a prison. While performing in California, Kekana’s bag was stolen, with his passport inside. When he went to the South African consulate to get a replacement, the government officials stalled. Difficulty after difficulty arose. Eventually, Kekana applied for political asylum in the U.S.

Eleven years after he left South Africa, Fana Kekana sat in a restaurant in the West Village in Manhattan. An icy winter wind blew through the door and a five-foot plant poked at his shoulder. He said it was difficult being so far away from home. He sent his two-year-old son to South Africa and didn’t see his son until he returned at age five, speaking a bit of Zulu. Still, perhaps it was easier to live in New York than near South Africa. Once he went to Zimbabwe for a festival. “The worst thing would be to live in Zimbabwe. I looked at the clouds in Zimbabwe and it was hard to believe it was the same sun, the same clouds as people were seeing in South Africa. I couldn’t help thinking that that cloud I was looking at might come down in Soweto.”

©1988 Steven Mufson

Steven Mufson, a freelance writer, is reporting on black political leadership in South Africa.