I was asleep and the phone was ringing. That was wrong to begin with. Unless there’s a special reason, my wife and I turn off our bedroom phone most nights. We go to bed earlier than the world expects us to, I guess, because if the phone’s on, it often rings. I must have forgotten to disconnect, because it was ringing now. I grumbled a hello and my friend Herbie came on full steam, blurting a non-greeting: “Didn’t I tell you never to trust them! Now do you believe me?”

“What happened Herbie, what are you talking about?”

“Didn’t you hear the news? They killed some reporter out in Arizona. Now will you listen to me?”

For months Herbie had been warning me that I was in danger. I was working on an unusual investigative project–unusual because the key source was a mobster. Herbie didn’t know the guy, but he didn’t like the setup: “They don’t talk to reporters. It’s a cardinal rule. Something funny is going on and you better be careful.”

I’m always a little careful. I try to protect Herbie by never knowing his address or phone number. For testifying against the mob, the federal government has given Herbie a new identity. He thinks the mob still wants to kill him and he could be right. Just to be safe, I try to make it impossible for me to give him up.

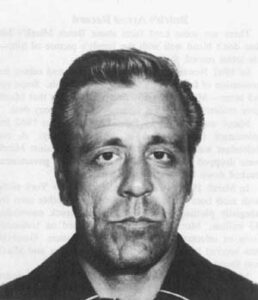

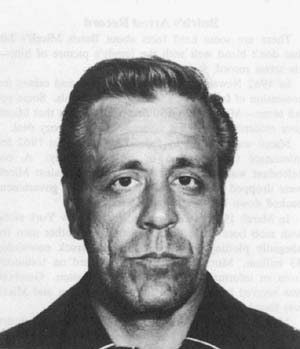

The Arizona reporter about whom Herbie was calling, Don Bolles, wasn’t killed by hoods. A bomb was planted in Bolles’ car by a social misfit, apparently serving a wealthy landowner. But Herbie’s alarm system went off when he heard about the Bolles case because he thought I was getting too close to a New Jersey hood named Frank “Butch” Miceli. For months I had been using Herbie as a sounding board, figuring that his years of dealing with mobsters might help me get some better understanding of Miceli.

When those conversations started in 1975, Miceli had been an investigative target, a minor figure at the edge of a story about corruption within a social-service agency. Part of the corruption was that agency employees had used federal funds to help build a swimming pool for Miceli with money that was supposed to go into a low-income housing project. I was working with two other newsmen on the story and we lucked out at the end.

Miceli was arrested on unrelated charges, so, instead of confronting him at his home, I arranged to see him inside the Bergen County Jail.

The setting was almost medieval. The jail’s more of a dungeon than a modern prison, a cone-shaped beehive made out of rough stone and iron bars. From the ground floor, you can look up inside the hive and see several floors of cells. Miceli was brought from his cell to meet me on the ground floor and we sat there on a bench and talked. Dressed in a loose-fitting uniform of drab green denim, Miceli stood out from the other prisoners. His posture was different–proudly erect. His hair was neatly groomed. He must have been allowed to keep his own shoes, so glossy they might have been patent leather.

Guards and inmates treated him with deference. As we started to talk, Miceli asked another prisoner who was passing by if he had a cigarette. “Sure, Butch, take these,” the inmate replied, eagerly giving him half a pack.

Our conversation centered mainly on Miceli’s backyard pool. I had expected that he would refuse to talk about how it was built or would lie to protect the people we were investigating. But, instead, he admitted getting help from his friends, including a construction superintendent who had been diverting men and materials from the public-housing project. Miceli said that he had thought the housing workers had helped out voluntarily, on their own time. I told him that we could prove that wasn’t true with time sheets and signed statements from several workmen. Their boss, Miceli’s pal, had ordered them to do the private job while on the project’s payroll.

The mobster really didn’t go to bat for his friend, saying in effect: “Hang him if you can, but I didn’t know the deal was dirty.” (Eventually the construction superintendent was indicted on federal charges. He pleaded guilty and was given a suspended sentence.)

As we were winding up, Miceli said something that jarred me. I forget the context, but it must have been something to do with his perception of right and wrong.

“You know what I really hate,” he said. “I hate those God-damn phony politicians who take my money and take my favors and then walk around pretending they’re better than me. At least I’m not a phony.”

I almost fell off the bench. I said, “Hey, Butch, I’m an investigative reporter. Those are the people I’m supposed to catch. Maybe we should be talking about them.”

“Come see me when I get out on bail,” Miceli replied. We made a tentative date to get together at his house.

Miceli grew up in Medford, Mass., also the hometown of one of his prime accusers, Vincent Teresa. Teresa is a mob informer who has written two books, “My Life in the Mafia,” and “Vinnie Teresa’s Mafia,” both co-authored by Tom Renner of Newsday. In the books and in sworn testimony before a U.S. Senate subcommittee, Teresa has identified Miceli as the head of a mob hit squad, a team of assassins.

“Butch Miceli will hunt me as long as he has a breath of life in him. That’s the way he is,” Teresa said in his most recent book. “What he can’t find out personally, he’ll have members of that enforcer squad of his try to find out. He won’t give up. When and if he finds me, he’ll pick the time and the place to try to whack me.”

Teresa’s books give this portrait of Miceli and how he grew:

As a youngster, Miceli idolized mobsters and tried to emulate them. His parents were too good to him and never challenged his lies. He used friends in the Social Security office to form a tracer bureau for crooks, locating persons who had skipped out on local bookies. Miceli had to flee the Boston area because another mob figure thought Miceli betrayed him. Teresa helped him tie up with New Jersey mob leader Joe Paterno. Paterno liked Miceli and made him his driver. Miceli became powerful when he took command of the hit squad, an internal mob police force that settled disputes with bullets.

In 1970 Teresa testified against Miceli in federal court in Boston. Teresa described how he himself has set up a crooked deal with a banker to turn fake bonds into cash by using the bonds as loan collateral. Teresa said that he telephoned Miceli looking to get a lower price on phony securities. Miceli beat the competition and allegedly delivered $50,000 worth of fake ITT bonds.

The jury believed Teresa’s story and U.S. District Judge Charles Wyzanski sentenced Miceli to ten years in jail. Six months later, Miceli sent a letter to the judge. The hand-written appeal tells a lot about Butch Miceli. Here are some excerpts:

“Dear Mr. Chief Justice:

“My name is Frank Miceli, I lived in East Paterson, New Jersey. I am 37 years old, I have a daughter 3 1/2 years old, I also have a mother and father who live in Medford, Mass., and a sister, with 6 children who lives in Medford, Mass.

“I am writing you this letter in hope, that you will consider it as a motion for reduction, under rule 35, United States Code. I am tired of hiring lawyers, and them not presenting the evidence I have furnished them with.

“I was sentenced March 15, 1971 to 10 years, section 4208-A-2, and I was sent to Lewisburg Penitentiary, where I am serving my sentence.

“Your honnor in your sentencing statement you said, in my transcript on page 188, (“I do not regard your case as being one which calls for the full service of the ten years.”) I think that you were trying to give me a break in the sentencing when you said this, and when you sentenced me under 4208A-2.

“But, the Parole Board, and the Prison, doesn’t look at the A-sentence. They only look at the amount of years you have. And this is how they judge you, and your Parole. It is common knowledge that here at Lewisburg, and it is told to you in the Parole Book, that they issue you, as an inmate, that you must go before the Parole Board twice, before they even consider giving you a Parole. And it is also known, around the Institution that the first time you go in front of them with a sentence like mine, you receive anyware from a 30 to a 36 month set off. The second time you receive half of a set off, as to the first one. Then they tell you after all this to go get a progress report. So you see you have almost all of your Maximum Release time in. Also, being that my sentence is 10 years, I am on Close Custody, Restricted mail, and cannot participate in some of the Classes that are available, for rehabilitation.

“I have gone through a great deal, in the last 16 or 17 months, and have also put my mother and father and daughter through the same problems. My mother and father have stuck by my troubles from the begining, and my troubles are killing them slow but sure. If I may explain.

“…my mother and father hired me a lawyer from Medford Mass, who new me since I was a young man, and who also new Mr. Teresa. Well he got so tied up, in trying to prove that the stuff in question, was counterfeit, that he forgot my charge was interstate. So he did not present my defense. In which I would have been found, not guilty. I had so much evidence there would have no question of my innocence. Then after I was found guilty, I fired this lawyer, and hired another. The other lawyer said, that all the evidence I had was supposed to be used at my trial. And that the only way I could present this evidence, was to get a new trial. Then I was told, that the only way I could get a new trial, was to come up with newly discovered evidence. Then I came up with newly discovered evidence, and was finally told, that he didn’t want to try to get me a new trial on this evidence. And thats when I told myself, and my mother and father, and my sister, to fire this lawyer also, and I would write you for help…

“I promise you, you will never hear of me again, all I want is to go back to my home, and raise my daughter, and repay my mother and father, for all the troubles, and expense I put them threw.

“Please give me a reduction, to a time served, or release me to Federal Supervision.

“Thanking You I remain

Frank Miceli

“PS. Please excuse my spelling, and handwritting. Thank you again.”

A week after receiving Miceli’s letter, the judge issued an order reducing his sentence from ten years to three years. He seemed moved by Miceli’s explanation of how the parole board operated. The judge’s order explained: “This court…expressly declared at the time it imposed sentence that it did not intend that defendant should be confined for the full period of his sentence.”

I think that one reason why Miceli agreed to talk with me after he was arrested in New Jersey in 1975 was that I already had written about him and had talked by phone with his mother and sister. With his arrest, I decided to cash in some of our file material and publish a profile of Miceli, even before we wrapped up the housing-project investigation. I telephoned his family in Medford, because I knew that Miceli’s mother had been active in politics and I thought she might talk with a reporter. The Boston Globe’s clippings file at the time had no entries on a hood named Frank “Butch” Miceli, but there were a few articles about his mother, who recently had been named to a third five-year term as a $9,000-a-year state labor commissioner.

Mrs. Madaline Miceli, then 68, said she hoped that news of her son’s arrest wouldn’t make the Boston papers. “There’s nothing in now and I hope it keeps out because I just got reappointed. I’ve been on there ten years…I think you know that we’re a very respectable family. We’re a good-living family and anyone can verify this. I was a presidential elector in Eisenhower’s campaign, so I couldn’t be very bad or my family very bad.”

She blamed all of her son’s troubles on Teresa. “He brought in so many innocent people that he has hurt by telling false rumors which unfortunately doesn’t help anybody. My daughter is a sacristan at the Catholic Church here in Medford and anyone would tell you what a wonderful girl she and her family are.”

Miceli’s sister, Rose Marie Pelusi, said that everyone in Medford knew that Teresa was a liar. She’s three years older than her brother, whom she described as a kind and gentle man. “I know my brother. I’m not with him 24 hours a day. I can’t say what he does when he’s not with me. All I can say is I don’t think he would ever hurt anyone deliberately.”

When Rose Marie and her brother were small, home was a brown, two-family house on Medford’s Main Street. The Micelis lived upstairs, a middle-class couple with just the two children. The father, Frank J. Miceli Sr., was a warehouse worker, loading and storing for the First National supermarket chain. Mrs. Miceli worked, too, but her major activity became Italian-American club affairs and Republican politics.

The family circumstances improved somewhat in 1965 when Mrs. Miceli’s political hobby began paying dividends and she got her first patronage appointment as a labor commissioner by then Gov. John A. Volpe. Also in the mid-sixties, Miceli’s father retired after 25 years with the warehouse and took a state job as an insurance examiner. Butch’s first job after high school also was with the state, as a truck driver for the Department of Public Works. Later he opened a toy store in Medford. He moved to New Jersey in 1960 and told the family he was working as a wholesale jewelry salesman.

Butch’s Arrest Record

There are some hard facts about Butch Miceli’s life that don’t blend well with the family’s picture of him–his arrest record, for example:

In 1962 Newark police arrested Miceli and others for possession of fake stock and obscene materials. Some got jail terms–Miceli got a $50 fine. Teresa says that Miceli gave evidence against his associates to get a cozy deal.

Miceli was indicted by federal authorities in 1962 for interstate transportation of stolen property. A codefendant was convicted and the charges against Miceli were dropped. Miceli’s lawyer said that the government backed down because it had a flimsy case.

In March 1970 Miceli was indicted in New York along with mob boss Carlo Gambino and three other men for allegedly plotting to rob an armored truck containing $3 million. Much of the case was based on testimony from an informant, John H. Kelly of Boston. Gambino was severed from the case for health reasons and Miceli was found not guilty.

My phone calls to his family in 1975 were prompted by new charges against Miceli, alleged bribery of a police officer, which he eventually admitted. Miceli had been caught up in a “sting” operation–a cop, pretending to be corrupt, had recorded payoff meetings on tape.

I asked Miceli’s mother if her faith in her son would be shaken if she were to listen to the tapes and hear him bribing a cop.

“I don’t believe it,” she said. “I don’t think it’s possible.” Miceli’s sister said tapes wouldn’t convince her: “I honestly would have to have my brother tell me that he did these things before I’d believe them.”

More than a month after meeting Miceli at the county jail, I went to see him at his home. It was a hot day and Miceli was dressed in a bathing suit and bathrobe. He led me to the backyard and we sat and talked at the edge of his pool. At 41 years old, Miceli was in bad physical shape, but it only showed in his legs. I didn’t know it then, but he suffered from multiple sclerosis. His upper torso was athletic looking, but his legs were withered as if the muscles had atrophied from lack of exercise. He walked stiff-legged, using his arms to brace his movements by leaning on railings and tables.

While he was out on bail, a grand jury was continuing to investigate Miceli and other mob figures in his circle. (No indictments were ever handed down.) The county prosecutor’s office was calling in persons who had been seen meeting with Miceli and his associates during the period that Miceli was dealing with the undercover cop. Much of our conversation that first day concerned the prosecutor’s tactics. Miceli said that innocent bystanders were being harassed by the prosecutor’s staff.

“All they’ve done is call people that have been seen eating with us, drinking with us, or coming to my house, or coming to places where I’ve hung around. They haven’t called any person for actual crimes.”

I asked him what his activities were that brought him into contact with the individuals who were being questioned.

“A guy could come and ask me for a job, and I’m in a position to get it for him. A guy could come and ask me for tickets to a play and I could get them for him. I could ask a guy to do me a favor and clean my car and he cleans my car. I could ask a guy to do me a favor and get me a discount on a barbecue and the guy does that. Or just general conversation where a guy comes down with his girl and he sits down and we have lunch or dinner together and we speak in general. Every single time that I sit down and speak to somebody or talk to somebody, it’s not pertaining to a legitimate or an illegitimate deal. This is all social relationship.”

“Do you deny you’re a member of organized crime?”

“I don’t even know what organized crime is. Nobody’s ever explained it to me. When somebody can explain organized crime to me, then I’ll answer that question for you. That’s number one. Number two, to my knowledge, I don’t belong to any organizations. Never have, with the exception of when I was a kid, I was a boy scout and I think a cub scout. I think those are the only two organizations I ever belonged to.”

“But the way you’re able to get favors.”

“It’s through many years of building up relationships with people, which average people do, only they say I’m different than average.”

“In other words, you have a lot of friends. Isn’t it true, though, that some of those friends are people who have been identified as members of organized crime?”

“Again you’re bringing up organized crime. What is organized crime? I want someone to define organized crime to me and then I will answer to the best of my knowledge what I think organized crime is,” Miceli said.

“Think of a franchise operation like MacDonalds,” I replied, accepting his challenge. “Think of a franchise-type company that operates in illicit areas, such as gambling, such as shylock loans, in some branches, perhaps even narcotics, some in prostitution, some in hijacking. Think of people that have certain territories that they handle.”

“That’s all fictitious,” he interrupted. “There’s no such thing as certain territories. There’s no such thing as a bunch of guys getting together and, just for instance, running a crap game and it’s an organized-crime crap game? Colored people have crap games. Why aren’t they organized crime? Puerto Ricans have crap games. Why aren’t they organized crime?”

“Have you seen ‘The Godfather’?” I asked.

“Which one?”

“Both”

“The first one I seen a little bit on television.”

“That’s how some would say you identify organized crime.”

“That’s wrong though. Why isn’t Watergate organized crime?”

“It’s just a different tag that you hang on something,” I said, fumbling for an answer.

“No, it’s a different tag that they hang on the Italians. That’s what they do. And you know that as well as I know that,” Miceli said. “Bruce, not to make fun of you, I know what you’re trying to tell me when you ask me about organized crime.”

He was enjoying himself. I could see the corners of his mouth move a bit as he resisted smiling.

“What I’m trying to say is this: how do I tell a reader what you are?”

“Right. How do you tell a person what I am? I’m the same as anybody else in this world. I’m no bigger. I’m no smaller. I’m no richer and I’m no poorer. I feel as though that everybody’s equal. The only thing that I feel as though is that the Italian people are being persecuted to cover up all these white-collar crimes. Because, all a guy has to do is make a big stock swindle. A legitimate broker goes into a brokerage house tomorrow. He makes a big stock swindle. And a guy out in left field is Italian. The guy that made the big swindle will get away with it and the Italian will go to jail. And he’ll be organized crime. This is my honest outlook on life. You say organizations. You’ve seen these pictures, ‘The Godfather,’ and you’ve seen these pictures, ‘The Luciano Story,’ and this story and that. These are all dramatized. Ninety per cent of these books that are written by these so-called informers–these people took advantage of the government.”

He began griping about Vinnie Teresa and then started ticking off the names of other informers he said were liars.

“What about Herb Gross in Lakewood?” I asked, trying to see if there was a mob party-line on my friend Herbie. “Do you know him?”

“No. I never met him. I don’t know him. Now these people knew from the day that they started their lives in illegal activities that they were eventually going to become FBI informers and write books.”

“You really think that it was that premeditated, or was it something that evolved?”

“Yes, no. There’s no such thing as a guy squealed because they threatened his family. Or the guy squealed because they didn’t take care of the guy’s family when he was in jail and this and that. That’s all baloney. That’s an excuse for all these informers…they have to find something to go to sleep with at night.”

And so began the poolside dialogues. When the New Jersey summer changed abruptly into fall, we moved inside to Butch’s kitchen. For nine months I visited his house two or three times a week, usually talking with him for an hour or so.

Herbie was right, of course. There was something funny going on. Butchie was feeding me a mixture of lies, myth and maybe some truth, for his own purposes. But that didn’t become clear until much later. Perhaps because of Herbie’s warnings, I kept my guard up with Miceli. Early in our relationship, without thinking much about it, I told him that we would have to operate under these groundrules:

I can never be your friend and you can never do me a favor.

Always remember that I’m an investigative reporter. I’ll remember what you say, so talk to me about your enemies, not your friends.

I deal in truth. If you lie to me, we’re through.

Butchie never did deliver the phony politicians whom he said he hated. But he let me inside his circle and I got a chance to feel the fabric of his life and the lives of people around him.

Despite the groundrules, I came to like him. I still think of Butchie as my favorite mobster. His Boston accent was disarming–it made him sound almost cultured. But little lies soon crept out. He was playing with me with that “Godfather” conversation. Long before video recorders became mass-market items, Butchie had one in his basement den. Sure, he had seen a little of the film on television–he had cassettes of both the original and the sequel before they were commercially available.

He changed me, this crippled mobster. In reviewing my interviews with him, I can see what I was and know that I’ll never again be as smug and self-assured.

But what I remember most are some moments when I think I saw the reality of Butchie’s life. Once I saw shame there, a shame I suspect is shared by other mobsters. In one of our later, kitchen conversations, he told me casually about his Sunday routine. He’s divorced and his daughter was living nearby with his ex-wife. Every Sunday Butchie would pick up his daughter, drop her off at church, and collect her again after Mass. I tried to tell him that he could go inside, that the Roman Catholic church had loosened up since he and I were kids.

“Naw,” Butchie said. “With a life like mine, I don’t belong in church.”

There was a sadness in his face and in his voice that seemed profound and real.

©1982 Bruce Locklin

Bruce Locklin, a reporter on leave from the Bergen Record, is investigating aspects of organized crime.