Record-breaking storms are wreaking havoc – compounding, not erasing, the difficulties of multi-year drought.

The renter’s home in Sanger, just outside Fresno, went dry in the spring. The well at one house in Madera has been on and off since January 2021. The homeowners in Dinuba can’t figure out why the water keeps getting lower, further out of reach. Meanwhile, the rainstorms keep coming.

While the contours of drought recede on the official California map, residential wells across its gutted Central Valley continue to run dry. California Department of Water Resources (DWR) well records paint a picture of a state in the midst of a climate-driven water crisis that seems absurd if not tragic on its face – too much and too little all at once, even in the same place.

One homeowner reached out to their local state representative for help – could they bring a pump to move some of those floodwaters down to their dry well? “I thought, wow, good for you for your creativity. I don’t think that’s going to work. But people are desperate,” said Jessi Snyder, director of the nonprofit Self Help which provides support for parched rural communities that are now also facing the devastation of flood. “It’s such an awful irony.”

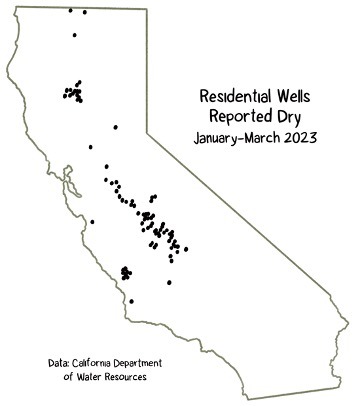

The depleted aquifers still bear the damage of decades of over pumping while floodwaters break through banks, berms and levees across the flatlands, inundating crops and towns. Between January and March 2023, DWR has received reports of 120 residential wells gone dry, 80 of which lie in the San Joaquin Valley, which is simultaneously facing a slow-motion flooding disaster, with millions more acre feet of water due to flow out of the Sierra in the coming months.

This “precipitation whiplash” is highlighting the extent of environmental devastation in the valley, along with the new risk of more extreme climate-driven storms and flooding. Water managers in the valley hope to put that water to work, relying on stored floods to limp from drought to drought – this makes up the backbone of many of their plans to reach “sustainability” as required by state law. In March, the plans covering a bulk of the valley were deemed “inadequate.” Those agencies now face imminent judgment and potential intervention from a state water board that is poised to finally step into the contentious Central Valley groundwater business.

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) was signed into law in 2014 amid what was at that time the state’s worst drought on record. It was California’s first comprehensive attempt at groundwater management after years of patchwork regulation. But like any modern water regulation, it was a package of deep compromise. The target for sustainability was 2040, and the measure of “sustainability” itself was vague. The new agencies that would craft plans and rules and enforce them would be organized locally, with control over defining their own borders and setting their own taxes to fund their operations. Some single basins became controlled by several different competing agencies who would all have to cooperate on an overarching plan. Those plans almost universally assumed that pumping would not stop or even slow for many years as a slow transition was carried out.

SGMA required engagement with and consideration of all beneficial uses and users of water. But existing water power structures were replicated in the SGMA system. Of 112 new agencies created in the seven San Joaquin Valley counties, 63 are moonlighting irrigation and water districts that manage water rights and allocations for agriculture – public agencies that work closely with, if not at the behest of, private industry. Even in cases where their borders may not include residential communities, the actions of every district will impact the fate of the shared water table, but only a handful have a codified role for residents who rely on private domestic wells.“One mistake that was made is not having the [sustainability agency] encompass the entire basin, instead allowing all this fragmentation to happen at the governance level,” said Mark Lubell, director of the University of California Davis Center for Environmental Policy and Behavior. “They should have just had a single agency that was going to cover each of the groundwater basins and said, everybody’s got to get together and form an agency with some basic governance rules that include formal representation of disadvantaged communities in some way.”

Building in local control without much if any restriction gave the new regulations the support they needed to pass. But the only way to get these new agencies to manage their basins was with “the carrot and the stick,” said former state senator Fran Pavley, who co-authored one of the SGMA bills. “You manage your own basins, fine, but you have to show that you’ll be sustainable within 20 years,” said Pavley. “But if you don’t do so, or you turn in your plans and they’re deemed to be inadequate, then here’s the stick. The state water board will intervene.”

Since they were first submitted for approval in January 2020, groundwater plans for the state’s critically overdrafted subbasins have come under heavy criticism from advocates for small farmers and disadvantaged rural residents. “The residents are not being included, when they’re really the ones that are most impacted by over pumping,” said Sonia Sanchez, senior community development specialist at Self Help. “SGMA did not have any explicit language around resident inclusion. It was all left up to the [agencies] to determine.” Even when agencies do the community outreach that SGMA requires, meetings are often held on weekdays during work hours, making public participation difficult.

But some say these plans may not be representative of what will actually happen to the water. Follow through varies from agency to agency, basin to basin — the result of the hyper-local control at the law’s foundation.

“So much time and effort has gone into just writing the plans that it’s detracting from the actual objective of SGMA, which is to slow this disaster and start to turn the ship,” said Jessi Snyder of Self-Help. Despite their passing plans, said Snyder, “there are agencies out there that are just washing their hands of the whole thing.”

Snyder sits on an advisory board representing disadvantaged communities at the Mid-Kaweah Groundwater Sustainability Agency, one of those with an “inadequate” plan. Aaron Fukuda manages the agency, along with the Tulare Irrigation District. “It’s very clear that people are getting confused with and lost in the program. They’re spending too much time and energy on the plan, and they’re losing sight of the implementation,” said Fukuda. “At the end of the day, if I have a failed plan, but I achieved sustainability, I’m happy.”

Last May, mid-drought, the district instituted groundwater allocations for its 201 farmers. The result was a 13 percent reduction in pumping, as measured by evapotranspiration. When these winter storms blew in, said Fukuda, they had a system in place to incentivize those farmers to take extra water and reduce flooding risk down river – they receive credits for taking water into their ditches and furrows, where it slowly percolates back into the ground, banked for future drought. “We’ve got to meter it down very slowly, and hope for another wet year where we bring it back up, and then we can take it down again,” said Fukuda. “We live in this cycle so that the average stays where everybody has their wells safely protected.”

This is the kind of flood managed aquifer recharge that many agencies are banking on. Few have been so willing to put their growers on water budgets just yet; they are more eager to spend their efforts on increasing supplies and storing extra water underground for later pumping. In places where the empty aquifers haven’t collapsed in on themselves, simultaneously increasing local flood risk, it’s a welcome project. But it’s unlikely to produce the quick results that farmers want or offset decades of groundwater abuse.

“Anyone with an understanding of groundwater hydrology knows that it takes years for aquifers to recover,” said Snyder. Meanwhile, a record snowpack is due to melt this spring and flood out of the Sierra peaks and into the valley flatlands. The two crises will persist.

Susie Cagle is examining the unintended consequences of California’s water policies during her APF fellowship year.