Sonny Carson is not the best known or even the most disruptive of New York’s freelance “black activists,” but he has proved the most painful thorn in David Dinkins’side. The two men’s names were first linked in the public’s mind in August 1989, just weeks before the Democratic primary that pitted Dinkins against Mayor Edward Koch. The jaded Bensonhurst slaying of black teenager Yusef Hawkins had set even the city’s nerves on edge and given Dinkins, who was promising to deliver racial harmony, a considerable advantage among both black and white voters. Then, on August 31, downtown Brooklyn erupted in a bloody racial free-for-all.

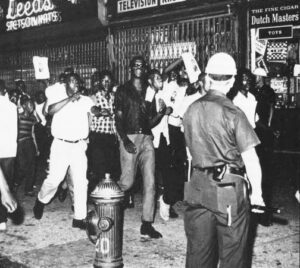

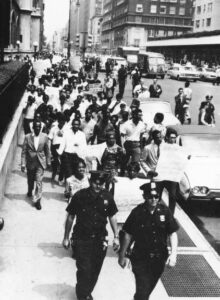

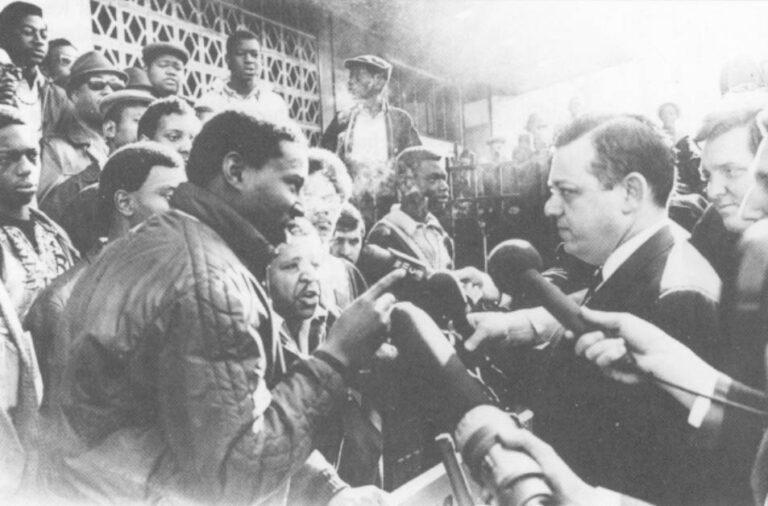

More than 7500 demonstrators, most of them black, marched six abreast down the borough’s main shopping street. Carson led the angry but disciplined column, brandishing placards and chanting rhythmically: “Whose streets? Our streets! What’s coming? War?”

At the foot of the Brooklyn bridge, the demonstrators met a heavily armed police guard determined to prevent them from blocking traffic on the span. Carson defiantly breached the police barrier and a 20-minute battle ensued. Forty-four cops and unnumbered protesters were injured, several of them seriously. But the biggest casualty, most New Yorkers agreed, was the Dinkins candidacy. How could Dinkins promise racial peace with a man like Carson gesturing menacingly behind his back?

Dinkins has been struggling ever since to find a way to live with Carson and the shadow he casts. About six weeks after the Brooklyn demonstration, in the middle of a close mayoral race, it emerged that shortly after the melee Dinkins’ campaign had paid Carson $9,500, supposedly to help get out the vote in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Skeptics charged that the money was simply a payoff, “insurance” against future Brooklyn marches. Within days, the press revealed that Carson’s so-called campaign organization was nothing but a shell–without an address, telephone or members. Under pressure, Dinkins’ people admitted that they had made a mistake, but still the candidate did not repudiate Carson. Then, with the papers still full of the payoff story, Carson called a press conference and, surrounded by leather-clad hoods, announced to the world that lie was “anti-white.” Only then did Dinkins publicly distance himself–not, for many white voters, any too persuasively.

Dinkins’ awkward dance with Carson was soon to become all too familiar to New Yorkers. The city’s first black mayor is a deeply cautious and moderate politician, eager to appeal to whites as well as blacks. Yet even in office, he has proved unable to distance himself from angry, largely separatist black leaders. Provoked again and again by the antics of men like Carson and Al Sharpton, Dinkins either turns the other cheek or, at most, vaguely deplores abstract “bigotry.” He has yet to criticize Carson by name; nor has he unequivocally repudiated the racially motivated boycott, organized by Carson and others, of two Korean groceries in Flatbush. Why can’t the mayor come out more decisively? Not, it seems, because blacks can’t criticize other blacks: Carson attacks Dinkins all the time, saying among other things that his mayoralty “stinks.” Yet apparently the criticism can only go one way: extremists can vilify moderates, but not vice versa.

It is a code that Carson knows well; he has been living by it for more than 25 years. A self-proclaimed “revolutionary,” unabashedly anti-white, he is not only radical in his beliefs, but the tactics he has relied on over the decades–death threats, intimidation, violent confrontations with police–put him quite outside the realm of what most people consider acceptable in politics. Still, many whites–and moderate blacks like Dinkins–feel that Carson has enough of a following that he must be taken seriously as a political player. In fact, no one knows how representive he is. Yet somehow, no matter how outlandishly he behaves, no one seems able to deflate or dismiss him. Not only that, but instead of seeming marginal, he maintains a hold on even far more powerful men like Dinkins. How does this work? What is the source of his influence? How is it that a man like Carson can have so much influence on the range of acceptable black opinion, undermining the moderates’ balance and ever tugging them to the extremes?

The event that drew Carson into racial politics–the threatened “stall-in” of the 1964 World’s Fair–was an early, dramatic lesson in just how this influence works. By 1964, the civil-rights movement was struggling to make itself relevant in the north, where the problem was not segregation–essentially a middle-class problem–but the tangled poverty and pathologies of the urban ghetto. The challenge from the beginning was to attract ghetto youth, and the Brooklyn chapter of CORE proved more successful than many other groups–thanks in large part to its unstinting militancy. In the early 60s, that meant more aggressive, more confrontational “direct-action” tactics: not merely sitting-in but dwelling-in for a week, lying down in front of bakery trucks and dumping garbage on the steps of municipal offices. The idea, as someone said at the time, was to do something that “drastically inconveniences people.” The purpose of the inconvenience–for negotiating leverage or simply to annoy white people–was already growing cloudy.

Brooklyn CORE’s proposed “stall-in” took this idea to its logical extreme. More than 2,500 cars were meant to run out of gas on the highways leading to the fair on opening day; hundreds of other CORE members would pull emergency brakes on subway trains and lie down on the bridges between the city and the fairgrounds. With all the world watching–and many thousands trying to get to the fair–CORE would effectively close it down, lodging a huge symbolic protest against discrimination. Never mind that the fair itself was in no way discriminatory and that the demands CORE put to the city were so sweeping as to be unmeetable. As Carson (who did not yet belong to CORE) noted several years later: “I think it had something to do with jobs, but it wasn’t important what it was all about; what was more important was the effect it had … it brought about [a] kind of pandemonium.” Just to threaten such an action gave CORE a moment of delicious revenge, placing “the city in a position that black people always find themselves in … a position of having to react.”

As it happened, the stall-in fizzled–the 2,500 cars did not appear, those that did were outnumbered by police and the city’s roads remained largely unobstructed–but not before CORE’s radicals had tasted an intoxicating new power. Not only had white New Yorkers utterly panicked, but the Brooklyn chapter also discovered that it could manipulate its much richer and better connected parent, the national CORE organization. CORE’s director James Farmer was against the stall-in from the start, but he had no answer to the Brooklyners’ claim that only they and their bold tactics could appeal to the increasingly impatient youth of the northern ghetto. After a long night of talk, national CORE repudiated the stall-in, but it had to make up for this censure by mounting its own protest at the fair–massive sit-ins and lie-ins–directed at only slightly more specific targets on the fairgrounds. Already, the radical tail was waving the moderate dog, and the black protest movement was losing its capacity to resist the pull of its own extremists.

In fact, in 1964, Sonny Carson was the very model of the ghetto youth that Brooklyn CORE aimed to bring into the movement. In his mid-twenties, out of work, thoroughly alienated from the white world around him, Carson was an all too typical product of the gangland Bedford-Stuyvesant where he grew up.

Already in elementary school, he was learning to steal pennies from newsstands. By junior high, he was an accomplished mugger, constantly high on drugs and firm in his belief that the only important human quality was remorseless aggression–whether directed against whites or blacks, enemy gangmembers or gullible women did not matter much in those days. Before he had finished high school, he was serving in a state reformatory, and even there he was known as one of the toughest boys, prepared to defy the parole board rather than bend his neck to anyone. By the time he joined Brooklyn CORE, Carson had tried the U.S. army, the civil service and the life of a grownup hustler; yet somehow, none of this could hold him. He was drifting more or less aimlessly when the stall-in galvanized him with its radical power politics. As for which branch of the movement spoke his language–the middle-class moderates or defiant nattionalists—Carson never had a moment’s doubt. “There was another Brother,” he has written, looking back on 1964, “named Martin Luther King”:

[He] was beginning to upset me because that philosophy he taught was spreading and it didn’t seem to fit right with me. That “turn the other cheek” business—shee-it. Malcolm, I think, was saying it right: that if someone hit you on one side of your cheek, then you lay him in the grave.

Carson rose fast in movement politics, and by 1967 he had become executive director of Brooklyn CORE. His roughhewn ideology was already in place–it remains constant to this day–and very much in tune with the nationalism of the time. Opposed to integration (he thinks mingling with whites can only be humiliating), scornful of the black middle-class (perpetrators of integration and traitors to their race), thirsty for open racial conflict (he believes that only fear will bring whites to make concessions): Carson personified the anger that filled the ghetto by the summer of the Detroit and Newark riots. It was then that Bobby Kennedy chose him to sit on the Bedford-Stuyvesant Development Corporation, a self-help effort backed by government and private groups. Asked why he was flirting with local toughs and militants, Kennedy explained: “These are the people we have to reach. Some people may not like it, but they are in the street and that is where the ballgame is being played.”

Meanwhile, the national civil-rights movement was struggling to catch up with the mood that Carson represented. Gone forever was the Gandhian nonviolence and integrationism of the early 60s. By 1967, mild-mannered Farmer had been replaced at CORE by the lean and angry Floyd McKissick. Less than a week after the Newark riots, McKissick defended them at a Black Power conference: it would simply be “foolish,” he said, “to try to sell nonviolence in the ghetto.” Once again, the supposed “followers” were leading, and the leaders scrambling to keep pace. Within the year, McKissick had been outflanked and supplanted by the still tougher Roy Innis. Though a rival of Carson’s, Innis had virtually identical politics–and his rise at CORE marked the triumph of a darkly bitter mood. Both he and Carson spoke loosely of violence. Neither had much time for whites. Both were committed nationalists who took the idea literally–who hoped to establish a “black nation” in America. (Carson announced in fall 1967 that Brooklyn CORE had bought a tract of land for a self-sustaining agricultural settlement.) And, like Carson, Innis derived his power from the perception that he represented the ghetto.

Carson left CORE, in 1968–he quit in a huff after a quarrel with Innis–but not before he had seen the movement virtually remake itself in his own image. Among the last speeches he heard at a CORE meeting was delivered by staunch old-timer, Whitney Young, head of the ever-moderate Urban League. Addressing CORE’s annual convention that summer, Young revealed how far even the center had moved left. This country “does not respond to people who beg on moral grounds,” he said. Blacks must develop “the power that America respects.”

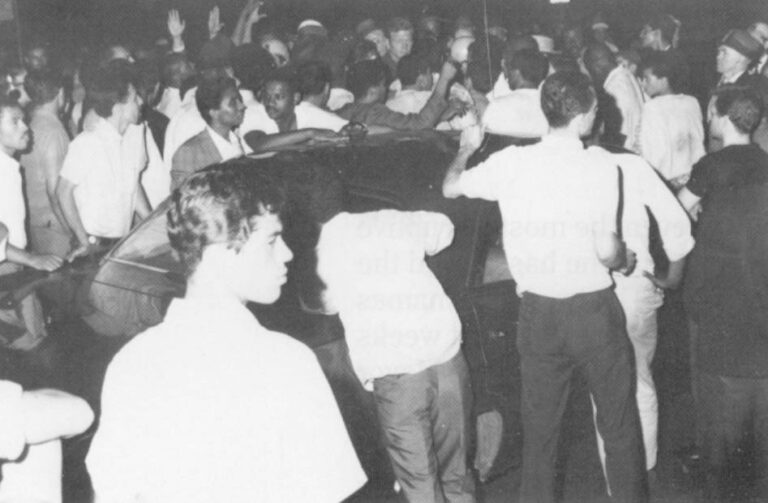

Back in Brooklyn, Carson was determined to do just that–indeed, he was already perfecting his techniques. For him, the long hot summer of 1967 was the opportunity of a lifetime. That summer, he did not have to manufacture the threat of violence; the very streets hung heavy with the possibility of unrest, and he played brilliantly on the city’s fears. Whether or not he and his followers actually encouraged rioting in Bed-Stuy remains a matter of some dispute; there is no hard evidence, though there are witnesses who charge this, and he himself admits that his CORE office provided a rallying point for angry youths. In fact, Carson’s game depended on just this uncertainty–and on his convincing the city that he could turn the violence on and off.

Mayor John Lindsay played right into Carson’s hands, coming out to Brooklyn on several occasions that summer to try to soothe him and enlist his help. With bands of kids roaming up and down the streets, looting and setting fire to trash cans, Carson and followers would sit with the mayor at CORE headquarters and tell him menacingly just how bad things were. “These kids are sore,” Carson said on one occasion. “If [the neighborhood is] burned it won’t be CORE’s fault …. We don’t want it burned down … but CORE won’t stand in the way.” What exactly he got out of this ritual is hard to say; lots of militants who played the same game got paid by the city or the federal government for their “help” in keeping the ghetto quiet. Certainly, Carson enjoyed the exercise: by the end of the summer he was calling Lindsay’s people in the small hours of the morning and insisting that the mayor or a top aide come out to Brooklyn “immediately.” Invariably they went–no matter how late or how frightening the meeting place–and invariably they were met by a new round of veiled and not-so-veiled threats.

No wonder Carson felt, through that summer of 1967, that he was an important player in the city. With both Lindsay and Bobby Kennedy paying court to him in Brooklyn–and the press obligingly printing every petty threat–he understandably imagined that there were no limits to his power. He began to look around for a place to wield his growing influence and soon found the perfect target in the Bed-Stuy public schools. With no particular authority but that of Brooklyn CORE, he announced he was going to “evaluate” 32 teachers, and after a few weeks he declared that all but five of them were “fired.” He made no effort to disguise what he thought was their key shortcoming: that because most of them were white, they could not help black students. And, as ever, his main tactic was a threat: “If [the schools superintendent] thinks we are kidding,” Carson told a reporter, “he had better wait until September and see what happens when those teachers … try to come back to our community.”

When neither the board of education nor the teachers’ union responded, Carson took the battle directly to them. First, he and a group of followers took over union headquarters, spending a night on office couches and making free use of the telephones. Some weeks later, he tried the same tactic at the board’s central office. This time, the cops were there ahead of him, and–by Carson’s own admission–he and his group provoked a nasty brawl that landed one policeman in the hospital. (He was struck on the head with a three-foot metal ashtray, then taunted with shouts of “I hope you die.”) Also that summer, Carson invited teacher-union head Albert Shanker to a “community” meeting in a Brooklyn school. Shanker was heckled and then prevented from leaving. When he appealed to Carson to call off the thugs at the door, Carson merely laughed at what he later described as “this great big honky union chief standing there, blotchy with apparent fright.” By September, Carson’s gang was illegally entering school buildings and accosting teachers in the halls, telling them among other things, “The Germans did not do a good enough job with you Jews.”

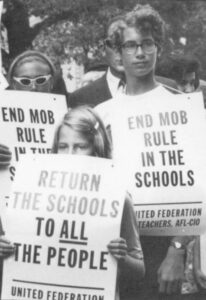

Within months, Carson’s activities in Bed-Stuy attracted the attention of more ideological militants pursuing the Black Power notion of “community control.” The idea behind community control made a good deal of sense: to try to get black parents involved in overseeing the education of their children. What’s more, by late 1967, a great many New Yorkers, black and white, Supported the idea, and it could conceivably have been achieved by peaceful means. Lindsay was trying to get it written into state law; the Ford Foundation was eager to finance a trial effort; even the teachers’ union was willing to try it on an experimental basis. Yet all this establishment power combined proved no match for Carson and his more rudimentary notions of control.

Carson did not run the Ford-financed experiment in community empowerment carried out in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Ocean Hill-Brownsville. He was not a key strategist or an important negotiator for the group of activists and educators (known as the “governing board”) who were given charge of the district’s schools. All Carson did was help them enforce their ideas–but in the end, his characteristic enforcement methods overshadowed everything else about the experiment. Certainly, his tactics made it all but impossible for most white teachers to cooperate, doing more than perhaps anything else to provoke the bitter teachers’ strikes that closed the city school system through the fall of 1968.

Carson’s methods were already in evidence in Ocean Hill in May, when the governing board unilaterally ousted 19 teachers–much as Carson had “fired” teachers in Bed-Stuy the year before. In Ocean Hill, too, a key charge against them was their race (and the fact that they did not seem loyal enough to the Black Power goals of the experiment). When the teachers’ union objected to the ousters, its representatives were intimidated in the schools. Carson and his men roamed the corridors at will, just as they had done once before in Bed-Stuy. The only difference now was that they had permission, and no one tried to stop them when they threatened Jewish teachers. (It was just such intimidation, and the ousters, that spurred the teachers to go out on strike.) Finally, when police were brought in to restore order in the district, Carson led what he called “the community” in resisting them.

On one of the worst days of the autumn, police tried to escort a group of union teachers to work against the wishes of the governing board. Cops and teachers were met on the steps of the school by Carson and some 50 of his men wearing police helmets and battle fatigues. After a tense standoff (Carson says there was violence), the teachers were admitted to the building but were given no work assignments. Later in the day, they were told to report to an auditorium in another school building. There, they found the walls lined with Carson and followers, now carrying sticks and bandoliers of bullets. The teachers clustered in the middle of the room as Carson’s men began to curse at them. “Wait till we get the lights out,” the men shouted, “We’ll throw lye in your faces. You’ll be very visible.” The lights in the windowless hall were flicked on and off; teachers were pushed and shoved and told they would leave the room only “in pine boxes.” When they finally did get out the building, escorted by police, they were–to say the least–reluctant to go back until both the board and Carson had been disciplined.

By the time the strikes ended, in mid-November, the crisis in the schools had become a two-way affair, with the teachers bitterness and their prolonged citywide strikes contributing heavily to the poisoned racial atmosphere. Still, there can be no mistaking Carson’s role in setting the tone that pervaded the city that fall, polarizing whites and blacks to the point where most wrote off the other race entirely. Where did Carson get that power? Was the community behind him? As usual, no one was sure. His rallies in Ocean Hill were never very large, and it took only a few dozen men to implement his intimidating politics. Still, he claimed to represent both the neighborhood and the rest of black New York–and as usual no blacks came forward to dispute his claim. Members of the governing board played this ambiguity for all it was worth: they gave the impression that they themselves were moderates–willing to negotiate and uncomfortable with intimidation–but then shrugged that they could not control Carson or the grassroots anger he represented. What’s more, by the time the strikes were over, there was considerable truth to Carson’s boast that he had converted thousands of black students into little “Sonny Carsons.” He made violent confrontation seem not only acceptable but glorious and convinced an entire generation of black kids that the city’s whites were their implacable enemies.

The year of the school strike was the peak of Carson’s power, but it was not the end of his notoriety. Throughout the next five years, he appeared only sporadically in the news–confronting school officals here, defending militants somewhere else, disrupting the state senate in Albany and standing by as the drapery in the hall was set on fire. Then, in 1973, he burst onto the front pages again when he surrendered to the police in connection with a local murder. He was by now something of a celebrity, riding the wave of radical chic that followed on the violence of the late 60s. He had written a book about his gangland youth and early radical politics; Paramount Pictures was preparing to make a movie of it; Carson was himself in New Haven, lecturing at Yale, when the police came to his house to arrest him.

There was never much doubt about what happened on the night of the crime. Carson’s base at the time was in a hotel in Bed-Stuy, where he and his followers kept what they called a museum of African artifacts. Several rare pieces and some money were stolen. Somehow Carson and cronies knew exactly who had done it and decided to take matters into their own hands. There were eight men in the posse, including Carson; all allegedly had guns. They found their victims easily enough, and one was fatally shot at his home in Brooklyn. The other was wounded and left for dead at a deserted spot on Long Island. He survived and testified extensively about what happened. Yet it never could be established with accuracy what exactly Carson’s role had been.

The trials–there were several and they were surrounded by publicity–dragged on into 1976. Carson spent much of that period caught up in the glittering world of Hollywood: consulting with Paramount, hanging out on the movie set, riding around in a limousine with a white chauffeur. When the film was done, he crisscrossed the country on a publicity tour, granting chatty interviews about black victimization in America. One reporter who met with him at poolside in Los Angeles said he looked as if he had been staying at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel all his life. As for his involvement in a murder case, it only seemed to add to his glamour as a streetwise militant.

In court, where he sometimes showed up in his bathrobe and slippers, Carson claimed that he and his gang had only been implementing justice. His victims were not only thieves, but drug-dealers; he had intended only a “citizen’s arrest.” Because he was black, he could not rely on the white police. Besides, he said, there would be no trial if he were not a famous militant. The case turned on the question of whether or not he had ordered the shooting. Carson said no; the trigger-man argued yes. But neither the gunman nor the surviving victim made very credible witnesses. (One was an accomplice; the other admitted lying on the stand.) In the end, the defense managed to discredit them and just about everyone else in the case as junkies, killers, perjurers or stickup men, and Carson was acquitted of murder. (He ended up serving 17 months in prison on kidnapping charges.) The day of his acquittal he stood up in court and told an applauding crowd: “I’m just happy for everyone, especially for the people in the community. It’s more a victory for them than for us.”

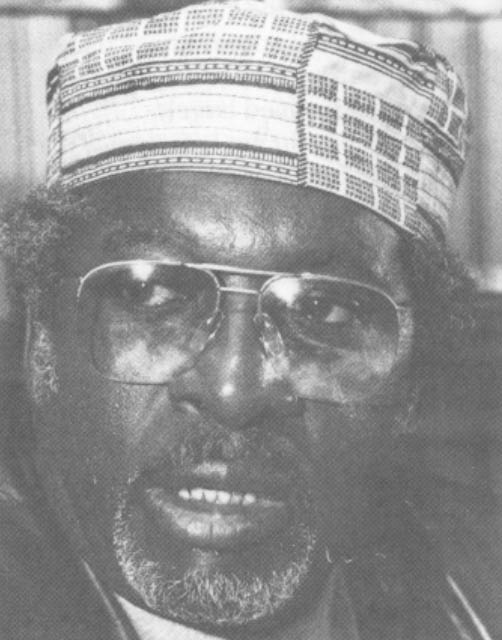

Today, more than 15 years later, Carson’s role in that community is no less murky than it ever was. No one outside his immediate circle is quite sure how strong an organization he has. It may be no more than a close-knit gang, though he regularly turns out scores of angry demonstrators in front of the Korean groceries. Not even associates will speculate about how he lives. (There was some talk at the time of the first Korean boycotts, in Brooklyn in 1988, that the protesters were extorting money from grocers. These rumors were never substantiated.) Carson’s political goals are still as vague as ever, though he now maintains informal ties to a group of Marxist revolutionaries known as the December 12th Movement. (Seven of its members were charged and acquitted in 1986 of a politically motivated armed robbery.) Carson makes no secret of his contempt for other activists like Al Sharpton, but still contributes in his own way to many of their causes. (At the time of the Howard Beach incident, for example, Carson provided a “security force” for black demonstrations in the white neighborhood where the original beatings and death took place.)

Of course, as the past 25 years show, the real size of Carson’s following makes little difference. The menace of his thuggish cadres, his unimpeded access to the press, the sheer shock value of the things he says–these will guarantee him a place in New York politics. What’s more, whether or not he represents most black people, he evidently speaks to something in the hearts of many. They may not approve of everything he does and may even deplore some of his most extreme methods. But there is clearly something in his manner that commands a wide respect. As one fellow radical, Coltrane Chimurenga, recently told the Village Voice, “Say what you want about Sonny, he always stands up for black people.” As long as the world is divided sharply into black and white, Carson’s appeal will remain–as it is today–virtually unchallengeable in the black community. As long as the battle lines can be drawn that starkly, there will not apparently be much room for scruples about tactics.

© 1991 Tamar Jacoby

Tamar Jacoby, a freelance writer, is researching race relations in several American cities.