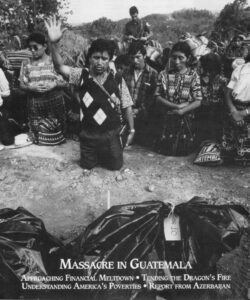

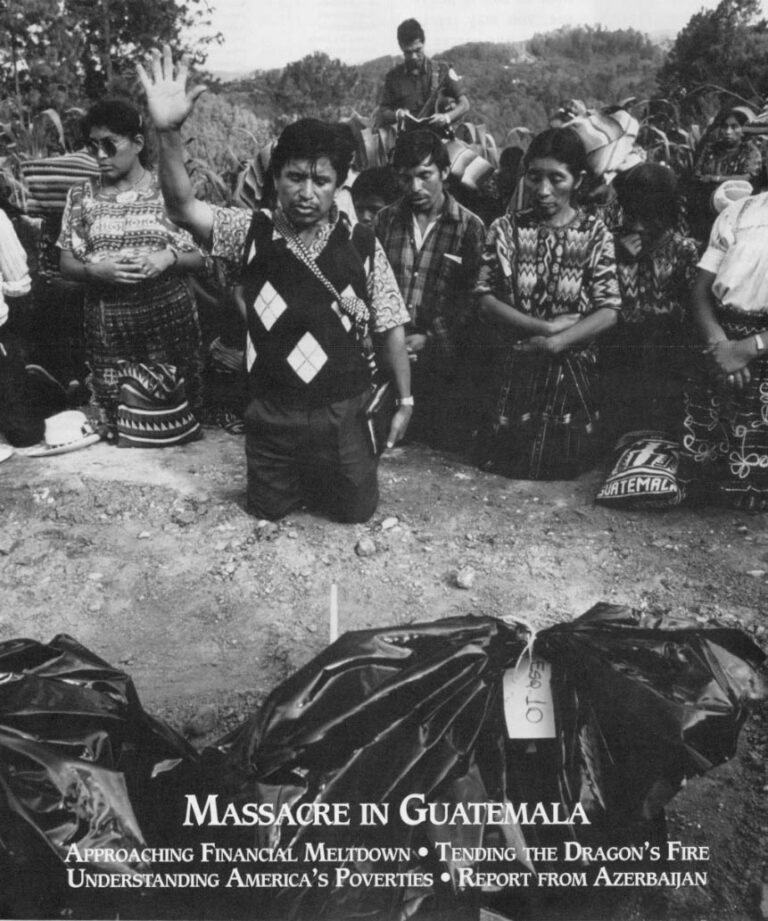

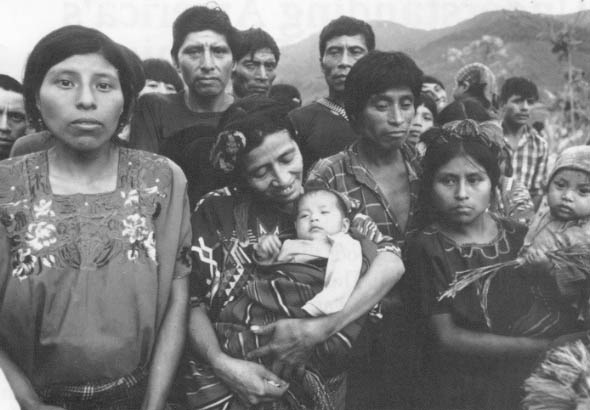

A noticeable hush fell over the small crowd of Guatemalan indigenious people. They watched in horror as forensic anthropologist Luis Miguel Alonso painstakingly unearthed the body of a young Indian boy killed in a massacre in 1983.

Indigenious women dressed in brightly-colored huipils dotted the green cornfield as a team of Argentine forensic anthropologists slowly uncovered evidence last August of a Mayan tragedy in the small village of Chontala. The village, in the western highlands of Guatemala, was part of the bloodbath by the army and civil patrols that engulfed this small Central American country during 1979-1985.

Layer by layer, Luis brushed away the rich soil to reveal what the onlooking people already knew-the boy had been shot in the head. As he continued, Luis revealed the. rope that tied the young boy’s hands behind his back had also reached around his neck.

Luis deducted that the boy had been killed by “tiro de gracia,” or a shot to the head at close range. The other twelve bodies the anthropologists unearthed suffered similar fates.

This mass grave contained 13 skeletons, bringing the total number of bodies exhumed in this tiny village to 26.

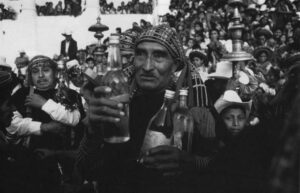

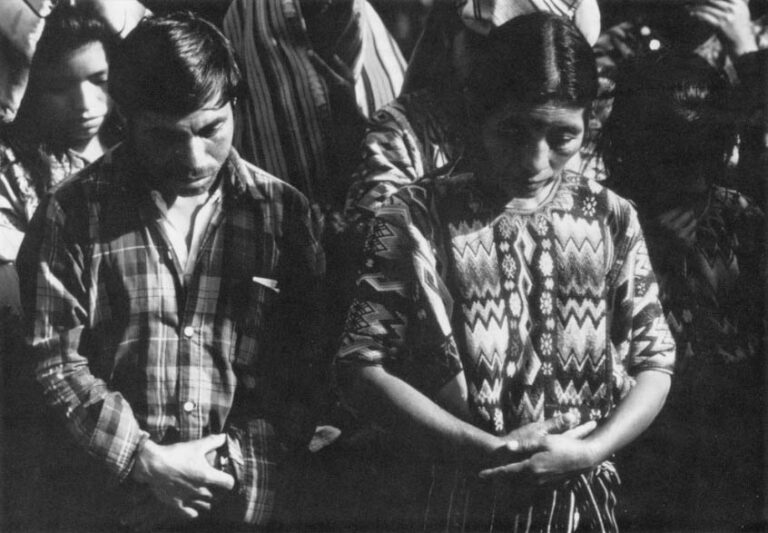

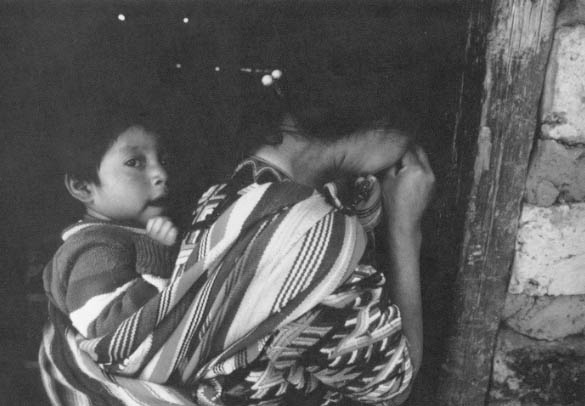

During this recent era of guerrilla insurgence and army action, thousands were killed, disappeared, displaced or made refugees. Most of the victims were direct descendants of the great Mayan civilization that populated the highlands when the Spanish conquistadors arrived to “discover” America almost 500 years ago.

The information that led to the exhumations was gathered by a widows’ organization, Conavigua. Rosalina Pu Gomez, Conavigua’s director, stood nearby, shaken by what she saw. All she could say was, “This is terrible, this is terrible. I hope now that people will believe us about what happened then.”

Another exhumation the week before uncovered the charred remains of seven other villagers. According to those present, most had been burned alive and then shot in the head.

The exhumations were carried out by the Argentines and Dr. Clyde Snow, an American forensic expert. The cynical truth about Guatemala, Snow said, is “they seem to be burying them faster than we can dig them up.

“A lot of people in the Army and the government talk a lot about human rights, but they don’t include indigenious in their definition of ‘human,’” he said.

The 27 bodies eventually exhumed in Chontala represent only part of the 115 people believed to be buried there. Those 115 bodies represent a fraction of the thousands of such clandestine graves thought to be scattered throughout the highlands of Guatemala, said Rosalina.

Conavigua is one of several popular organizations that have come to life during the first six years of democracy that have followed 30 years of miliary rule in Guatemala. Others organizations include CERJ (“all are equal”), GAM (“mutual support group for the disappeared”) and the Communities in Resistence of the Sierra and Ixcan.

CEFJ documents abuses by the army and civil patrols in the zone of Quiche. The general patrols were formed in 1983 under the dictatorship of General Efrain Rios Montt.

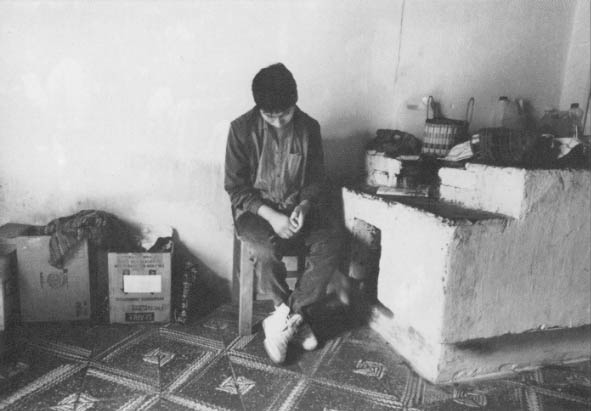

Indigenious men between the ages of 16 and 65 are required to serve 24-hour shifts guarding their villages every week or two weeks, depending on the number of men in the village. They are not paid for the patrol, and are given aged M-1 rifles to protect the villages against leftist rebels.

Although the Army states that the patrols are voluntary, indigenious men who refuse to serve are threatened and sometimes murdered by active patrol members or leaders. CERJ sees the civil patrol as a tool of the Army to further control and terrorize the indigenious population.

The risks are great. Twenty-three members of CERJ have disappeared or been killed since the group was founded in 1988.

GAM announced recently that it had information about seven clandestine gravesites, dating to the early 1980s, which hold more than 50 bodies.

The Communities in Resistence are composed of indigenious who fled into the remote mountainous regions more than eight years ago. Army officials are on record as saying these communities are rebel “collaborators and combatants.” This is denied by the well-organized communities, whose members say they fled army repression and nothing has changed to initiate their return. Although the rebel insurgents number only 1,500 by army estimates, they still pose a threat to the army in areas near where members of Communities in Resistence live.

Members of the CPR have demanded that the government formally recognize them and that the areas of Quiche, Heuhuetenango and the lxcan be demilitarized. They’ve asked that the army immediately cease the bombardments of their villages and the capture of their members and finally, that the government and army permit them to live in their villages with freedom of movement and commerce.

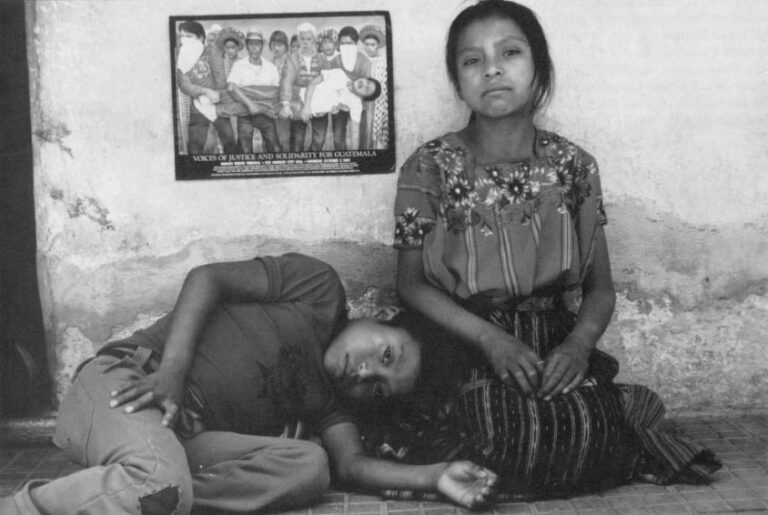

These popular and Indian movements which were formed under the first years of democracy are now under increasing pressure under the presidencey of Jorge Serrano. Threats, disappearances and the level of violence in Guatemala has increased dramatically in the early months of Serrano’s presidency.

CEPJ president Amilcar Mendez fled the country last fall due to threats. Two international news agencies, one from Mexico, NOTIMEX, and one from France, IPS, evacuated their offices in the capitol during September. A month earlier, a bomb was deactivated on the ninth floor of the building El Centro, in which NOTIMEX has its offices. The offices of human rights organization CERJ and the wire service, Reuters, are on the twelfth floor of the same building.

In a recent protest march by human rights groups, Catholic Bishop Abelino Ramazzini spoke about the recent solar eclipse that covered Guatemala. “It seems that Guatemala still lives in an eclipse… we still live in darkness.”

©1992 Vince Heptig

Vince Heptig is a freelance photographer based in Guatemala City.