Since Pearl Harbor, the United States has been in a constant state of either fighting or preparing for war, a strange fate for a liberal democracy that has allowed the military to have enormous influence on our way of life. New revelations this year about crime in the weapons industry resonate strongly because America has entwined so many of its essential attributes with warfare, for better or worse.

Although the foundation for vast military-industrial power grew during World War I and throughout the next two decades, the structure was permanently secured by the Second World War. It is to those years that one must turn to understand why efforts at disciplining the way the U.S. arsenal is purchased have never brought much change.

By 1939, a handful of aviation companies had struggled through the Twenties and Thirties nurtured by relatively small but profitable military contracts. The Great Depression had come just as a few firms were beginning to cultivate a civilian market for their aircraft, capitalizing on the public’s fascination with Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 transatlantic stunt. The industry was still young and pliable, with a coterie of designers and financiers able to regroup quickly after setbacks. Even during the depths of the Depression, there was seed money to support the most brilliant engineers, either from the government or private backers.

Grumman Aircraft, for example, opened for business on January 2, 1930, without contracts, products, or customers. Leroy Grumman, a Cornell-educated engineer who had served as a Navy test pilot after WWI and then worked for aviation pioneer Grover Loening, brought together 21 men and $58,825 on the strength of this youthful experience. Most of the money came from personal savings and family largesse among six investors who also formed the company’s management core. Roy Grumman’s stake was the largest, at $16,875. His “plant” on Long Island was a rented cinderblock garage that had previously housed a car dealership.

Within seven years, the company’s annual billings stood at $1.9 million with sales of $1.7 million. About $5 million worth of contracts were completed by the end of 1936, when Grumman moved to a 120-acre site near Bethpage that has been its home ever since. All but a tiny part of this incredible rise during the worst economic disaster in American history came from military work for the Navy, which Grumman decided to pursue from the beginning instead of commercial transport. At the start of WWII, Grumman was in a natural position to receive the Navy’s avalanche of business for carrier-based fighters.

The Glenn L. Martin Company (which became Martin Marietta in 1961), also made it through otherwise rough times by building warplanes for the government. After minor though technically distinguished production in WWI, the company concentrated on building a bomber for the Army. Glenn Martin himself was not a trained engineer, but a single-minded businessman and pilot who had spent years on the barnstorming circuit to support early ventures. He gradually was able to attract the best engineering talent of the day to his enterprises, including Donald Douglas, who designed a bomber accepted by the Army in 1920.

After Douglas and five other Martin engineers left the company that same year to form their own, the Army snubbed Martin by awarding production contracts for the bomber to three other manufacturers. For the next ten years, Martin worked exclusively with the Navy, garnering some $17.8 million in contracts for dive-bombers and torpedo planes by 1933. The company also began selling bombers to foreign governments, including Argentina, Turkey and China. By the outbreak of WWII, it was well-situated to produce heavy warplanes for the United States, Great Britain and France.

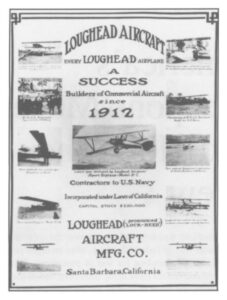

Glenn Martin’s roots in the do-it-yourself years of aviation were similar to Malcolm and Allan Loughead’s, who like Martin, rose from the dust of rural fairgrounds to become respectable businessmen. They, too, capitalized on the technical genius of others, in this case designers John K. Northrop and Gerald F. Vultee. They weathered a series of bankruptcies that even few military contracts could not prevent until achieving solid success with Northrop’s streamlined “Vega” aircraft, first sold to publisher George Hearst Jr. and flown by most of the aviation celebrities of the Twenties. With business booming at the end of the decade, the company (now spelled Lockheed) was sold to a larger corporation three months before the Crash of 1929.

By 1931, however, the parent corporation was itself a victim of the Depression. Its Lockheed subsidiary, which had been bled of everything except its illustrious name, was acquired for $40,000 by a group of four investors led by 35-year-old Robert E. Gross. Gross was neither an engineer nor a pilot, but the son of a wealthy Boston family whose fortunes lay in the relatively depression-proof coal business. From earlier financial involvement with the budding aviation industry around Los Angeles, he owned the plans for a promising all-metal passenger plane. Along with his family safety net, this and the Lockheed name were enough to keep financial support available until the company turned out its successful “Electra” twin-engine transport for civil and military customers. By the end of the decade, it had joined the ranks of major aircraft manufacturers, building hundreds of various Electra models for commercial airlines, the U.S. government and the British Air Ministry.

Lockheed’s stiffest competition in the transport market came from Donald Douglas, who had started his own company in the back room of a Los Angeles barbershop in June 1920 with $40,000. By April 1921, he had won a contract to produce three experimental torpedo bombers for the Navy, where his former M.I.T. aeronautical engineering professor had become chief of aircraft construction and repairs. Backed by Harry Chandler, publisher of the Los Angeles Times, Douglas obtained a $15,000 loan to finance construction of the warplanes, which led to steady Navy business and spin-offs for civilian transport. By 1928, the company’s net worth stood at $2.5 million.

Production of military aircraft kept Douglas financially sound throughout the Depression. Working capital increased from about $2 million in 1928 to $3.3 million in 1933,.allowing the company to develop its famous DC series of passenger planes for TWA and American Airlines. Prior to World War II, Douglas sold 623 DC-2’s and DC-3’s, not including initial orders for military versions. Douglas was known as one of the premier builders of civilian passenger aircraft, but its $69 million backlog at the end of 1939 consisted of 57.9 percent military export orders, 34.6 percent War and Navy Department orders and just 7.5 percent domestic and foreign civil orders.

Two other men whose reputations traced back to WWI, John Northrop and James McDonnell, also stood poised with their own companies at the start of WWII. Northrop, a self-educated designer whose aircraft already had made fortunes for others, was well-known within the industry and had operated a subsidiary of Douglas from 1932 to 1937. In 1939, Northrop incorporated his own company with the help of LaMotte Cohu, a WWI Navy pilot and former president of American Airlines. This management combination and rumblings of war in Europe brought precipitous success, with $20 million of unfilled orders for the first year of business alone.

James McDonnell never gained the personal technical reputation of Donald Douglas or Jack Northrop, but many years later he would absorb the Douglas business and far surpass Northrop as a military contractor. Educated as an aeronautical engineer at Princeton and M.I.T. just after WWI, he hopped between a number of aircraft companies for the next ten years before settling at Martin as chief engineer from 1933 to 1938, where he was responsible for several major bomber projects. In July 1939, he split away to found his own company, which rebounded from a $3,892 loss during its first year by subcontracting for established warplane producers and then pioneering carrier-based jet fighters for the Navy.

On the eve of WWII, thus, the companies were in place that would eventually dominate the military-industrial establishment. To be sure, there were a few others–such as CurtissWright and Consolidated Vultee–that were larger at this point and would carry a heavy burden of production during the war. But they became fodder for corporate mergers and did not survive as namesake entities, instead disappearing into such present-day conglomerates as General Dynamics and Rockwell International–just distant reflections of corporate mergers that now had nothing to do with original pioneers.

What kind of business world did these young companies face? By January 1942, President Roosevelt called for production of 60,000 warplanes in that year alone, plus 125,000 the next. These were fantastic goals, yet no more stupendous than the actual output curve: 3,000 in 1940, 19,000 in 1941 and 96,000 by 1944. The controlled profit margin on wartime contracts hardly was a disincentive, given the magnitude of orders and the small number of companies that took most of them. (Out of wartime expenditures of about $315.8 billion, the War Department spent about $179.9 billion and the Navy Department about $83.9 billion. Through 1944, the armed services contracted with some 18,539 firms, but 100 corporations received at least two-thirds of the contracts and 30 companies almost one-half. Lockheed, for example, realized a $30.4 million profit on sales of $1.98 billion during the five years ending in December 1944. This was almost ten times the total profit of the company during its first eight years, yet represented a return on sales of only 1.5 percent.)

For the government’s part, 20 years of interwar planning resulted in a mobilization system that was a refined version of WWI’s; i.e., a War Production Board controlled by elite corporate interests, based on the mutual needs and benefits of industry and the military. Labor, small business, and non-business civilian committees within this structure had little power. Although there was not as much flagrant corruption as in WWI, efforts to replace the WPB with an office staffed by civil servants and advised by all major interest groups–a notion endorsed by Senator Harry S Truman, among others–were derailed by Roosevelt.

The military had almost unlimited authority to determine its own requirements, which big business then supplied. After the war, there was a dip in this partnership during the immediate demobilization, but large Cold War military appropriations soon built up a permanent symbiosis. “National security” replaced “military necessity” as a catch-all justification for maintaining the status quo.

Contemporary procurement scandals in the weapons industry have occurred because there is no firm boundary between public and private interests. Jobs, information and capital all flow across an open border patrolled by a minuscule number of watchdogs. Although specific crimes might be new, the system that makes them possible dates to America’s last victorious war effort nearly half a century ago.

©1988 Wayne Biddle

Wayne Biddle, a freelance writer, is reporting on defense spending from World War I to Star Wars.