(BELFAST) — “Sometimes people were beaten up first, and there were fractures underneath, so you had to be careful when you removed the tar, ” says Sister Kate O’Hanlon, the buxom and motherly head nurse at the emergency room of the Royal Victoria Hospital in West Belfast. “It wasn’t actually tar, it was thick diesel oil. The oil is not as bad as burning tar, but it all makes a real mess. You remove it with eucalyptus. The Supply Department said we were using more eucalyptus than anywhere else in the United Kingdom… Sometimes they threw paint on people instead of tar. We had to call the painting foreman in, he told us how to remove it. We use acetone.

“I think they gave up tar and feathers because it made too much of a mess for the people who were doing it. Kneecapping is a cleaner job for them. “

Andy Tyrie, Fu Manchu moustache, heavy sideburns, stomach showing between button holes in his shirt, is head of the Ulster Defense Association (UDA), the strongest Protestant paramilitary group, and he claims to be, and quite probably is, a family man looking forward to his upcoming trip to Disneyworld. “Their punishment all depends on what they did, he says. “We might give them the same punishment back they gave someone else. Say they beat up somebody, the same might happen to them. For a vefy serious offense, say a rape or they really beat somebody badly, they might be kneecapped.

“This is not a normal society. You have to instill fear in those sort of people, but it never works if it occurs over a long period of time. People get used to being threatened. I know someone who has been kneecapped three times and is still doing the same things he was kneecapped for. “

Tom is a skinny 16-year-old car thief from a miserable housing project, Catholic, not hostile, not angry, not political. A blue eyesore graces the back of his hand, a bad tattoo he penned himself. In Northern Ireland, kids 12 to 22 years old who break into shops and homes are called hoods, and while some of Tom’s neighbors would lump him in that category, he claims he doesn’t belong there, that there is a difference between his pursuits and those of the others. “Id never break into a pensioner’s house, ” he says. “Id never break into anyone’s house; that’s not right. “

He admits he has been stealing cars since he was 10, that he has been in on the theft of over 200 autos, and that he has been caught just four times, once when he was liberating a car from a dealer’s showroom. He never steals from the neighborhood, however (though this may have more to do with availability than with any personal moral code). Asked why he goes in for the pastime at all, he says, “Because there’s nothing else to do. “

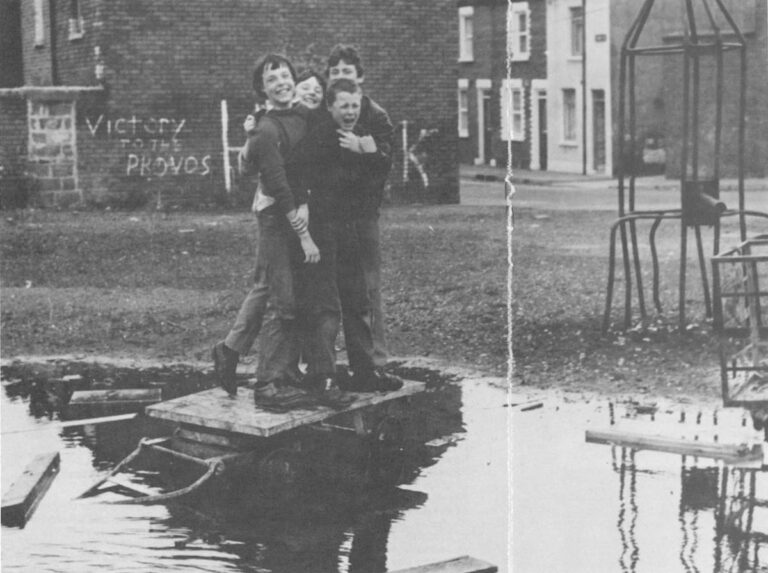

He is by no means unusual, just one of maybe a hundred kids in West Belfast who take cars out for night time cruises. Sometimes at the end of the night the joyriders set the cars aflame, sometimes the cars are abandoned by one set of kids and torched by younger ones. The flames are spectacular.

That’s just the way it is. Despite the return of police patrols to almost all of Belfast’s neighborhoods, thefts, break-ins, and vandalism are becoming more common, justice is often roughly administered, and some normal urban activities like evictions, electricity service cutoffs, even the serving of a summons, often cannot be performed. “Let’s face it,” says the press officer of the housing authority, “in parts of West Belfast there is no law and order.”

The housing official is wrong — there may not be law, but there is order, and far from a black mark on the province, the situation is really a compliment to the Northern Irish. A very normal life prevails. Women walk the streets in all neighborhoods, at all hours, without fear of rape. When people talk of the drug problem they mean valium abuse by housewives and mothers, not heroin addiction, which is almost unheard of (in fact, there is almost no market for even marijuana). One’s chances of being murdered are far greater in several American cities. There may be a revolution going on, and the revolutionaries may well be winning, but most people simply choose to ignore it.

And those people remember the good old days just 12 years ago, when the police force was half its current size, when the prisons weren’t full, and when there were no soldiers in the streets. And while street crime here may be no worse than in any other major city in the United Kingdom, to those who remember the old days, the current crime rate is unacceptable, and worse, it is multiplying at no small speed. According to insurance industry figures, the number of incidents of theft in 1979 was 50 percent higher than the figures for the previous year, and the amount of property involved went up 400 percent. And it is not the paramilitary groups which are pushing those figures up — it is the common thief, and in some cases, organized gangs of them.

A major factor in the increase in the statistics is the teenage rage for joyriding. In 1979, 1600 cars were stolen in and around West Belfast, and by the first week in June of this year, another 718 had been recovered in that area. The vast majority of the thieves are 16 and under. The commander of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) station on the Springfield Road tells of one case when his men captured two 8-year-olds in a stolen car, one at the wheel, the other on the floor operating the pedals.

Were it mere theft, the trend would probably be noted, denounced, and forgotten. The teenagers of West Belfast, however, are driving the cars at army checkpoints and not stopping. Unsure whether the car bearing down on them is a teenager playing Ulster roulette or a terrorist who is not playing at all, soldiers shoot at the speeding vehicles. Since the first of the year, three kids have been killed and nearly a dozen have been wounded or seriously injured in crashes that followed the Army’s gunfire.

The phenomenon is peculiar to Catholic West Belfast, and the deaths have only fueled anti-British sentiment there. “You steal a car nowadays,” says Esther O’Sullivan, a West Belfast community worker, “and the penalty is death.”

For the young thieves, however, death seems to be not the penalty, but the ultimate kick. Social workers in Catholic housing projects tell how hard it is to get the young interested in anything at the community centers. “I have to give them something more exciting than throwing stones at soldiers,” says Moya Hinds, a social worker at the Lenadoon estate, “and I can’t compete.” Some social workers, alarmed at the joyriding problem even before the first deaths, have set up a stock car racing program, with the former thieves driving autos they have purchased from junkyards. Maurice Hayes, former head of the Community Relations Commission, was initially skeptical when told that the program had worked in London and was therefore bound to work in Belfast. Hayes didn’t think the racetrack was enough. “You’ll need to have someone shooting at them as well,” he said.

“They are stricken by the death of a friend, but it has no lasting effect,” says Father Matt Wallace, a priest and organizer of a youth club in Lenadoon. “There was a kid killed joyriding out here on the Glen Road, but they were all out there the following night doing the same thing. Even killing them has no effect. I think death and injury is a normal thing, it is not a significant event in their lives.”

He admits he has been stealing cars since he was 10, that he has been in on the theft of over 200 autos, and that he has been caught just four times, once when he was liberating a car from a dealer’s showroom. He never steals from the neighborhood, however (though this may have more to do with availability than with any personal moral code). Asked why he goes in for the pastime at all, he says, “Because there’s nothing else to do. “

He is by no means unusual, just one of maybe a hundred kids in West Belfast who take cars out for night time cruises. Sometimes at the end of the night the joyriders set the cars aflame, sometimes the cars are abandoned by one set of kids and torched by younger ones. The flames are spectacular.

That’s just the way it is. Despite the return of police patrols to almost all of Belfast’s neighborhoods, thefts, break-ins, and vandalism are becoming more common, justice is often roughly administered, and some normal urban activities like evictions, electricity service cutoffs, even the serving of a summons, often cannot be performed. “Let’s face it,” says the press officer of the housing authority, “in parts of West Belfast there is no law and order.”

The housing official is wrong — there may not be law, but there is order, and far from a black mark on the province, the situation is really a compliment to the Northern Irish. A very normal life prevails. Women walk the streets in all neighborhoods, at all hours, without fear of rape. When people talk of the drug problem they mean valium abuse by housewives and mothers, not heroin addiction, which is almost unheard of (in fact, there is almost no market for even marijuana). One’s chances of being murdered are far greater in several American cities. There may be a revolution going on, and the revolutionaries may well be winning, but most people simply choose to ignore it.

And those people remember the good old days just 12 years ago, when the police force was half its current size, when the prisons weren’t full, and when there were no soldiers in the streets. And while street crime here may be no worse than in any other major city in the United Kingdom, to those who remember the old days, the current crime rate is unacceptable, and worse, it is multiplying at no small speed. According to insurance industry figures, the number of incidents of theft in 1979 was 50 percent higher than the figures for the previous year, and the amount of property involved went up 400 percent. And it is not the paramilitary groups which are pushing those figures up — it is the common thief, and in some cases, organized gangs of them.

A major factor in the increase in the statistics is the teenage rage for joyriding. In 1979, 1600 cars were stolen in and around West Belfast, and by the first week in June of this year, another 718 had been recovered in that area. The vast majority of the thieves are 16 and under. The commander of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) station on the Springfield Road tells of one case when his men captured two 8-year-olds in a stolen car, one at the wheel, the other on the floor operating the pedals.

Were it mere theft, the trend would probably be noted, denounced, and forgotten. The teenagers of West Belfast, however, are driving the cars at army checkpoints and not stopping. Unsure whether the car bearing down on them is a teenager playing Ulster roulette or a terrorist who is not playing at all, soldiers shoot at the speeding vehicles. Since the first of the year, three kids have been killed and nearly a dozen have been wounded or seriously injured in crashes that followed the Army’s gunfire.

The phenomenon is peculiar to Catholic West Belfast, and the deaths have only fueled anti-British sentiment there. “You steal a car nowadays,” says Esther O’Sullivan, a West Belfast community worker, “and the penalty is death.”

For the young thieves, however, death seems to be not the penalty, but the ultimate kick. Social workers in Catholic housing projects tell how hard it is to get the young interested in anything at the community centers. “I have to give them something more exciting than throwing stones at soldiers,” says Moya Hinds, a social worker at the Lenadoon estate, “and I can’t compete.” Some social workers, alarmed at the joyriding problem even before the first deaths, have set up a stock car racing program, with the former thieves driving autos they have purchased from junkyards. Maurice Hayes, former head of the Community Relations Commission, was initially skeptical when told that the program had worked in London and was therefore bound to work in Belfast. Hayes didn’t think the racetrack was enough. “You’ll need to have someone shooting at them as well,” he said.

“They are stricken by the death of a friend, but it has no lasting effect,” says Father Matt Wallace, a priest and organizer of a youth club in Lenadoon. “There was a kid killed joyriding out here on the Glen Road, but they were all out there the following night doing the same thing. Even killing them has no effect. I think death and injury is a normal thing, it is not a significant event in their lives.”

While joyriding is a West Belfast phenomenon, both Catholic and Protestant communities are suffering from an increasing number of burglaries and armed robberies of shops, most of them carried out by their sons and daughters, 12 to 20 years old, labelled hoods and hooligans by the local press. The thefts are most common in working class areas, and the thieves owe their success, in part, to the low police presence there. In some Catholic areas, like Divis Flats, for example, the police enter only in armored land rovers, and the officers don’t leave the vehicle for fear they would be stoned, or worse. The RUC admits that its response time has declined significantly in the last decade. When burglaries, thefts, and armed robberies are reported, the police purposely delay responding, sometimes even until the next day, as they have lost several comrades by arriving at the scene of a reported crime only to find it is really an ambush planned by the Provisional IRA.

In the absence of the police, or simply their scarcity, the paramilitary groups claim to be the guardians of the public order, sometimes even getting into competition with the RUC, trying to locate and punish a criminal before the police do. The paramilitaries’ performance, however, inspires little confidence. Residents are often unsure whether they have just been robbed by hooligans or by their alleged protectors, or if the two groups don’t have some common membership. In late February, an editorial in the Andersonstown News, a Republican community newspaper, came down hard on the Provisionals for their ineffective performance, asking if the IRA was behind the robberies, if they were supplying guns to thieves, if they had any control over who used their weapons and what for. In the following issue, the Provos responded, denying responsibility for the robberies, and claiming to be in hot pursuit of the hoods who had pulled off two recent hold-ups. “When we do have access to them,” said the reply, “The IRA will take the necessary action.”

The “necessary action” in these cases is usually kneecapping — punishing culprits by shooting them through the back of the leg. Years back, people were tarred and feathered, but that punishment is very rare now. The RUC didn’t keep kneecapping statistics for the first four years of the troubles, but between 1973 and 1979, the police say there were 756 kneecappings, 531 of them Catholic, 225 of them Protestant. The actual number of victims is around 700, however, as some people have shown themselves to be slow learners and have been kneecapped two or even three times.

Punishment shootings are totally non-sectarian — Catholics shoot Catholics, Protestants shoot Protestants. The number of such shootings varies considerably from year to year; in 1975, the peak year, 189 were recorded; the lowest number occurred in 1978, when there were 67; there were 41 in the first four months of 1980.

Other than for armed robbery and theft, people have been kneecapped for drug dealing, disobeying orders, sleeping with the wife of a man imprisoned for the cause, and for having disagreements with paramilitary group footsoldiers. “They don’t like admitting that they shot people who disagreed with them politically,” says Dan McGuiness, “and after they shot me they tried to say they had made a mistake, that they got the wrong person, but that’s rubbish. They questioned me for 15 hours.”

McGuiness, 26, now a solicitor and city councilman, was shot in 1972, two days before his 18th birthday. He lived in a Republican area, and was not involved in politics at any great level, but had let it be known that he supported the police. He was lifted from his house at 2 am on July 17, 1972 by two men who moved him from house to house around the district. During questioning he was burned on the neck and wrist with cigarettes, beaten with a belt buckle, and sliced on the back of his head with a razor blade. “The interrogation was much worse than being shot,” he says. “Finally I was blindfolded and tied to a lampost at a quarter to six in the evening. It was a short, sharp pain, and that was it. A passerby stopped his car and took me to the hospital, but he left without giving his name. I didn’t know until I got there that I’d been shot twice, once below the knee that broke my right leg, and one bullet embedded in my left thigh.”

“They told me to get out of the area, but afterwards I was much more determined to stay. I had hardened considerably.”

“Back four or five years ago, people were getting kneecapped who should not have been kneecapped,” says Richard McCauley, press officer for the Provisional Sinn Fein, the political wing of the IRA. “Because of the structure of the IRA at that time, decisions could be made at the local level. Now the structure is more controlled, things are done on a much more rational basis.”

“First, no one is kneecapped who is below the age of 16,” says McCauley, “For anyone below that age, you go and have a word with the family and a word with the kid, you put pressure on the parents to punish him severely. He might get a beating. I’m not talking about breaking his arms or legs, but a beating is a beating. Sometimes the kids are put under house arrest [told not to leave their home] for seven days. That’s a useful punishment, and generally the kids go along with it.”

If the child continues in his thieving, says one pro-IRA community worker, the IRA “will have to take action against the father…. They’ll beat him up and sometimes bar him from all social clubs in the area, so he’ll end up havin’ to go into town to drink.”

“There are degrees of kneecapping,” says McCauley, “and first they are given all sorts of warnings. You can be shot once or twice — once in each leg. Most are not actually shot in the kneecap, but in the thigh. They are in hospital for a day or two, and they hobble around for a week after. It’s more the scare that’s effective than the injury — it’s awfully scary to sit and watch a man with a gun pointing at your leg. On the rare occasion when they are shot in the knee, they are out for a number of weeks or months, but you have to be very bad to get shot in the knee. If you are very, very bad, you are shot in the kneecaps and elbows. But there is a definite procedure gone through, a series of warnings, it goes on for two or three months.”

According to an RUC report on the subject, the shooting usually takes place in a vacant house, graveyard, back entry, or on waste ground, where the victim either lies face to the ground or stands facing a wall. Protestant kneecappings, say the police, are done exclusively by the UDA with a .22. Their victims often escape with a flesh wound and don’t file for compensation (under the law, people who are not members of paramilitary groups can collect personal injury compensation for “malicious injury”). There is an oft repeated story that the UDA have used a Black and Decker drill to do the job, and the tale has been taken as fact at even the highest levels of government (the Secretary of State made reference to it in a speech in the House of Commons in 1974). However, according to police and Belfast knee surgeons, the story is apocryphal.

Catholic kneecapping is done with a variety of weapons, and the victims do file claims for compensation, usually saying they don’t know why they were shot or who did the shooting. The compensation office would quote no figure for a typical kneecapping claim, saying only that the payment would vary depending on the damage and on the individual (a professional athlete, for example, would probably get a higher settlement than a desk clerk); however, according to two victims, the payments range from about $800 for a flesh wound to $4,000 to $5,000 for bone damage and complications, and someone severely crippled could expect far more.

The strangest thing of all is that it is called kneecapping, as the truth is that the kneecap is very rarely injured,” says Dr. James Nixon, an orthopedic surgeon who wrote a dissertation based on a study of punishment shootings occurring between September 1974 and January 1975. Of the 86 cases he examined, only four kneecaps had to be removed. “It’s not kneecapping,” Nixon says, “it’s a back of the knee injury. Which is not to say it isn’t nasty. “

Nixon says that when the bone or major blood vessels have not been injured, the victim can be out of the hospital in a few days, but more extensive damage can have the patient in for three or four weeks. Amputation occurred in about 10 percent of the cases in the study, and he estimates that one in five of the victims will walk with a limp for the rest of their lives. Some will also bear what he calls a tattoo: when a gun is fired within inches of the skin, carbon particles discharged with the bullet speckle the flesh. All tattooing is based on carbon, and so the effect is the same, though the design leaves much to be desired.

Once a month, Nixon runs a clinic at the Crumlin Road jail, where terrorists and what the army calls “ordinary decent criminals” mingle. “I’m seeing a surprising number of men who were kneecapped ten years ago who have made no recovery,” he says. “Some of them suffer from residual paralysis of muscles in the lower leg. One fellow, for example, has lost all sense in the sole of his foot, and he gets sores there…. Surprisingly, I haven’t seen arthritis develop, I think because the incidence of joint damage is very low.”

“It’s a gruesome injury, but it has taught us a lot about the treatment of gunshot wounds.”

Kneecap victims get no psychological counselling, and since they usually have no money, they have no choice but to go back into the neighborhood they came from, where they are intended to be limping examples for those who would stray from the straight and narrow. “It always crosses your mind when you see a young man with crutches,” says Father Wallace, the Lenadoon priest, “he may have a football injury or some other problem, but you always wonder what he’s been kneecapped for.”

The old concept of shame following punishment is still applicabie among older victims, but young hoods have become particularly calloused. “All kneecapping does now is get government compensation for the person who gets shot,” says Des Forde, head of the Greater West Belfast Community Council. “It’s money in the bank if they don’t make a mess of it, if it was a clean job. As a deterrent, it’s not working anymore.”

“You ask them, ‘How’s the knee?”’ says Father Wallace, “and they’re not emotional or embarrassed about it. They’ll tell you, ‘Oh, it’s fine,’ or ‘I’m going back tomorrow for a checkup.’ They joke and talk about it freely, and everyone knows.”

Wallace tells of visiting one teenager in the hospital: “The first thing he says to me is, ‘Father, is it true I get $3,000 for each knee?”’

“The way these hoods see it,” says the Sinn Fein’s McCauley, “if you were kneecapped, that’s something to be proud of, and if it’s been done twice, that’s better, they’re looked up to by other hoods. It’s not a very happy state of affairs because we are not dealing effectively with the problem. We are only scratching the surface. But you’ve got to do something. Our people demand that we do something.

“I have talked to people who demand that if the IRA wants to seriously deal with the problem of hoods, they’ll have to shoot them dead, and there has been considerable pressure on the IRA to do just that. But they won’t do that hopefully … they’d just be playing into the hands of the Brits.”

There is a considerable risk involved in the IRA or the UDA doing anything at all. Kneecappings must now be done by hooded men, as many of the young hooligans are willing to tell police who shot them. If the shootist gets picked up anywhere along the way, he faces a certain jail sentence. Also there is the question of fitting punishment to the crime — maiming for a theft or a series of thefts is a little severe, and neither side seems ready to do it on a day-to-day basis.

In order to maintain their positions within their communities, however, the paramilitaries must appear to be doing something. The IRA bolsters its position by occasionally shooting a spate of hoods during a short period of time thereby putting the fear of the Lord into the ones who escape seniencing. Mary McMahon, the city councillor from Republican Clubs, claims that 23 young hoods were kneecapped in the Ballymurphy estate during a two week period in 1978, and that one spot favored by the shooters became known as “Kneecap Alley”. The Provos issued a statement, she says, saying that the group had been shot for “antisocial behavior”.

The effect is to quiet things down for a brief period while the hoods lie low, but once the heat has passed, the thieves reappear and the local grief starts to build again. Tom, the car thief quoted at the opening of the article, says he evades punishment simply by staying away from the local Provisional drinking club. He says he can name 40 other kids in his neighborhood who share his nighttime passions, and that few of them have ever been punished or even threatened. Youth workers on both sides of the religious divide also claim that many of the hoods are the sons of IRA and UDA members, or on the periphery of the organizations themselves, and the only kids who get punished are those with no such connections.

No one is satisfied with the current situation, except perhaps the hooligans. The British are trying to work the police force back into all neighborhoods, but at this stage policemen walk in Republican areas only when accompanied by an army patrol, the soldiers aiming their guns at the locals and the rooftops, the police trying to act nonchalant. Yet many — perhaps most — of the people in Catholic neighborhoods are glad to see the police return, despite the fact that the force is 98 percent Protestant (Catholics, once 20 percent of the force, have been intimidated and no longer sign on). “This is the dilemma,” says Father Wallace. “The people here want the police, but they don’t want the police as they are. I personally would not trust the police. I deal with them, but I don’t trust them.”

The level of distrust is extraordinary, part of it rooted in the charges of torture levelled at the RUC in the past few years, some of them substantiated. Both Catholics and Protestants have claimed that the police are playing games with the hoods. One theory has it that the police are doing nothing about the hooligan element, picking some of them up but letting them go without being charged, in order to make the local residents so furious with their plight that they beg the police to come back into their areas. Some Catholics believe the police and the Army make deals with the hoods, letting them go in exchange for information about local Republicans. The hole in the theory is that the hooligans would know almost nothing about the IRA, except in rare instances, and so would be useless as informers. They might be useful, however, in sowing distrust and suspicion in a community. “I think the police just put in the big mix,” explains one Republican, a former internee.

There are a thousand explanations for how the situation got to this point, but many of them start in the poverty here. Dave Wall, a solicitor and an instructor in criminology at Queen’s University, thinks joyriding is “quite a reasonable response to the conditions these kids live in. Their parents are on the baroo, they live in a damp, rat infested flat, and Sunday is a grim day because the checks don’t come in ‘till Monday. They’ve never had a luxury in their lives. They see people in big cars going down the Falls Road. They go downtown and see the nice things rich people are wearing, the clothes you can buy in the shops. And really, what’s the difference between two years in Divis Flats and two years in Crumlin Road Jail? Not much, and at least Crumlin Road is a change.”

“I strongly believe that a lot of crime is precipitated simply because there is a total lack of any other opportunity for these kids. They adopt a nihilistic approach to life,” Wall says, “which is quite realistic.”

©1980 John Conroy

John Conroy is spending his fellowship year reporting on the “Social and Economic Consequences of the War in Northern Ireland.”