(BELFAST) — If everything had gone according to plan, Harry Toner would be a wealthy man today. At 60, he would be taking it easy, enjoying the profits from the hotel he and his wife built up from nothing, resting comfortably on his impeccable reputation in the industry.

Instead he is running a catering service for the Belfast City Council and struggling to make the mortgage payments on his home. All he has to show for the once flourishing Hotel Windsor is a pile of debts and a medal from the Queen for his services in the industry, a medal about which he has an Irish Catholic’s mixed feelings. A lesser man would be broken completely, but Harry Toner struggles on, proud that his three children got good educations, proud that he never paid protection money, proud that no one got killed in his hotel.

“Every once in a while, something would happen and there would be a surge of feeling,” says his wife Moira of the last decade here, “a feeling that this would be the end of it, that we had reached the dregs and the depths, that this was the most awful thing that could happen and it would stop now, and that right-thinking people would do something. But God, what could they do?”

“We really couldn’t believe it could go on for so long,” Harry says. “It goes on for five years and you think, ‘this is it, it can’t go on for another.’”

The Toners opened the Windsor in 1960, and just before the troubles started they spent $95,000 adding a new wing. Even in 1969, the year the violence began, they had a bad month in August when the situation was very hot, but still managed to make a lot of money. However, two years passed and the troubles didn’t. By 1972, businessmen who formerly filled the hotel on weekdays were staying away as much as they could, and when they did come they refused to spend the night, either doing their business from the airport or flying in and out the same day. Tourists stopped coming altogether.

Catholics from the west side of Belfast, meanwhile, were getting too frightened to travel into the Protestant east, where the Windsor was located, and so they stopped booking the hotel for wedding receptions and banquets. At the same time, Protestants started avoiding the hotel because the honorable proprietors were Catholic.

Catholics from the west side of Belfast, meanwhile, were getting too frightened to travel into the Protestant east, where the Windsor was located, and so they stopped booking the hotel for wedding receptions and banquets. At the same time, Protestants started avoiding the hotel because the honorable proprietors were Catholic.

Harry Toner tells one story to show how bad things were: In one weekend in 1972, he had managed to book two Protestant functions. It was at a time when sectarian hatred was at fever level, when Protestants were boycotting Irish made goods and refusing to accept the Republic’s coins and currency. On this particular Friday, Toner had to make a last minute substitution for his table butter, as the day’s delivery had been rancid, and his supplier sent him individually wrapped packets of Kerrygold, a brand made in the South, as a replacement. When he put the butter on the table that weekend, his Protestant customers looked down their noses at the label and ate their rolls dry.

As year of violence followed year of violence, the local paramilitaries hit at the Windsor from every direction. Bomb scares became a local sport, and the delinquents who phoned in the hoax would trot down to the hotel parking lot to watch the evacuation. The Windsor was bombed twice, but by comparison with what was happening to other hotels, the damage was slight. The Toners rebuilt, though they eventually had to find a new construction crew, as the firm that had done all of their earlier work was Catholic and would no longer take jobs so deep in enemy territory.

The Ulster Volunteer Force, (UVF), the most militant Loyalist gang, solicited the Toners for a donation to its widows and orphans fund, local code words for protection money. The Ulster Defense Association, a more powerful and slightly less violent group than the UVF, muscled their way into the pub on the Windsor’s grounds, intimidating the other customers and taking it over as a club of their own. The Toners, however, had no intention of running a UDA club, and so they just closed it down.

The Toners’ friends, meanwhile, were telling them to get out of the business while they still could, and their accountant joined the chorus. Many of the Toners’ competitors turned to the liquor and disco business to try to bolster their sagging trade, but Harry Toner hated that idea. He hated the music, he hated the customers, he hated the damage they caused. A solicitor told him that what he needed was a good fire, that he knew just the people who could arrange it, and that he would be perfectly justified in taking that out because the civil authorities were no longer providing the services they should, they were no longer capable of protecting him. The Toners weren’t interested, and they hung on, hoping for peace, but their debts were getting larger and larger.

Finally, in 1978, they put the hotel up for sale. They were very lucky to be able to get rid of it at all, even at a price that would have shamed them years before. The buyer was the Royal Ulster Constabulary, Northern Ireland’s police force, and the once grand Windsor is now an RUC administration building.

“It took me 18 months to start thinking straight,” Harry says of the depression that followed the sale. “The trauma was terrible. We were just going through the motions. “

There are hundreds of men like Harry Toner, men and women of middle age who gave the best years of their lives to a hotel, a bakery, a candy store, a bicycle shop, who played it all by the rules and are now bewildered, the foundations gone. If they had been corporations, they could have simply written off the Belfast operation, and raised prices in Dublin and Edinburgh. But they weren’t, and they held on until they lost money, then held on some more, wringing their hands, glancing to heaven, chain smoking until their fingers turned brown. The Toners survived, they will come back, they have plans. Many, however, don’t recover, and walk about as Harry Toner did, “just going through the motions” in a functional stupor.

After the violence and destruction of the first years of the troubles, the British government devised a personal injury and property compensation scheme for those who suffered as a result of riots or terrorism. The scheme has saved thousands of businessmen, but many others have fallen through the plan’s loopholes.

Jim Kennedy, for instance, the owner of a large bakery firm, lost 6,000 customers in the first years of the troubles when Protestant paramilitaries told his deliverymen that they were no longer welcome in certain areas. While Kennedy could claim compensation for the vans which were stolen from the company to be used as barricades, there was no provision for customers lost due to intimidation. In 1979, the company went under. Kennedy lost the business his father started 70 years ago. He feels that he let down his stockholders and his employees. There is no compensation for that.

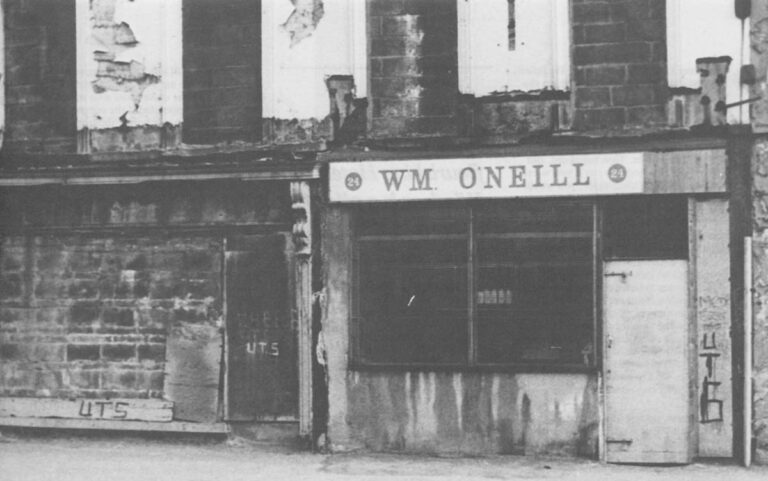

Protestants have suffered as well. One merchant spent years building up a dress shop in a working class area of Belfast, intending to have a legacy to pass on to his son. Now, however, the neighborhood is a shell of its former self, full of abandoned buildings, and it is all he can do just to stay afloat. He can’t sell the business, as no one is interested. His son doesn’t want it, and who can blame him? For that man too, there is no compensation.

Gordon Mawhinney, 37, is probably the country’s leading authority on property damage compensation, and his experience has been firsthand: His office has been damaged by bombs seven times. On the streets of downtown Belfast he has seen soldiers scrape bodies into plastic bags, and he speaks of the horror of seeing a head on the end of a shovel on one sunny afternoon. He has had friends killed, and friends who have killed and gone to jail for it. He lost all of his hair from shock — not just the hair on his scalp, but the hair on his arms and legs and eyebrows as well — after one bomb-filled afternoon in which he thought his wife and son had been killed at a beauty salon. He later discovered they had escaped injury because his wife had run five minutes late for her appointment.

Mawhinney’s job is to get people back into business after bombings and fires. “I see people at their most distressed everyday,” he says. “I have had clients put out on the street in their nightclothes with not a thing left in the world. But I try to take a very detached view. I have to.”

Flaws in the compensation procedures, Mawhinney says, have allowed some people to benefit considerably from the troubles, making fortunes immorally, but not illegally. He cites the case of a hotel purchased for $25,000 destroyed by a bomb shortly afterward. “The court gave the owner $300,000 to reinstate. He failed to do so, and there was no way to get the money back, and that was not uncommon between 1969 and 1977. If you assured the judge you were going to reinstate, that was it. People bought old buildings, insured them for full replacement value, and then burned them down. That happened. But the law has changed now, so if you weren’t putting up the building again, you would only get the value of the building destroyed.”

“I have personal knowledge of people who made hundreds of thousands of pounds individually,” Mawhinney says, “and in a large number of these cases, the people had no intention to reinstate.”

Mawhinney believes that the cases of compensation fraud are small in proportion to the number of claims, but large in relation to the amount of money involved. And most of those suspected of fraud are getting away with it; Mawhinney says that for every ten cases that the compensation authorities send to government prosecutors, only one results in criminal charges.

Of course, no one has any hard figures on the number of businesses torched by their owners or the number of shopkeepers who have paid terrorists of one persuasion or the other to do it for them. “One has one’s suspicions,” says Barry White, columnist for the Belfast Telegraph. “If you want your place burned down, you know who to ask to do it.”

Similarly, no one has any idea how many small businesses are forced to buy “insurance” from guerillas of one stripe or another. Some argue that the protection rackets are in decline, others claim that they still flourish, “I know for a fact that our builders are paying,” says one housing official who has spent a lot of time in the Protestant Shankhill, “and I don’t care what anyone else tells you, most if not all of the stores there are paying. I have seen it collected.

All of this is hard to put in perspective. After reading 10 years of press reports on the combat here, many visitors are surprised at the air of normality which prevails. The problem is that the war is acted out in very few theatres, most of them working class, and while businessmen in those areas have suffered tremendously, the rest of the province can easily plod on, ignoring the battlefields.

“For a time, ten, twelve years ago, I used to sit here and worry. I’d think, ‘So-and-so got blown up today, that means we lost a contract,” says W. A. Galbraith, manager of Rentokill, an extermination company. “We lost some business, but it’s not like that now. We’ve learned to live with the thing, which is a terrible thing to say, but it’s a fact.”

Probably most shopkeepers in Northern Ireland would say they have not been significantly affected by the war, and there are whole towns full of people for whom the fighting might as well be in Afghanistan for all that it concerns them in their daily lives. Even in Belfast, and particularly in its suburbs, there are those who have seen violence only on television, who sometimes half apologize to foreign newsmen because they have never been caught anywhere near a bomb, a riot, or a shooting.

Sometimes, however, one finds victims in even those safe places, people caught not in their own fire, but in the heat from someone else’s. One finds that in commerce there is a delicate balance, and if one species is destroyed, another is affected somewhere further down the line.

When tourists stopped coming, for example, the bedsheets and tablecloths in hotels remained unsoiled, and so laundries across the province suffered, and laundry employees were thrown out of work. In April, 1979, the secretary of the Ulster Farmers Union warned of the danger to crops presented by the increasing rabbit population; one factor in its increase, he said, was the reluctance of sportsmen to go into the fields with guns for fear they would be mistaken for terrorists. Tattoo artists have suffered a small loss of trade because recent legislation forbids them to work on minors, who were fond of getting sectarian slogans etched in their skin.

According to John Simpson, a Queen’s University economist and BBC commentator, the pool of professional people in Belfast has shrunk considerably. Middle management appointments are made from a smaller group of applicants, Simpson says, and people are now getting positions in business and at universities who would not have been appointed if the competition was of the level it was before the troubles. Performing artists and some athletes have been reluctant to make Belfast a stop on their tours, which has hurt the entertainment industry, and a good number of doctors have emigrated. British Airways pilots refuse to stay here at all, and a year ago the airline confessed that it cost $800,000 a year to fly their crews to Glasgow every night simply because they refuse to stay in Northern Ireland.

On the other hand, some businesses have boomed during the troubles. Glaziers have done very well, thanks to the bombing campaigns, as have roofers and loss adjustors. The compensation laws require that no claim be paid a business or shop which has not taken adequate precautions, and so security has been the province’s growth industry in the last decade. “If peace breaks out tomorrow,” one diplomat here says, “thousands of people would be thrown out of work due to the collapse of the security business.”

And just as security firms have been encouraged by the troubles, so too have common thieves. Armed robberies and break-ins, once rare, are now as common as the presence of soldiers. “Large corporations can absorb the costs,” says Eileen Lavery, a Fair Employment officer, “but for a small shop, one more holdup by a 12 year old with a plastic gun can be the margin between profit and loss.”

In mid-March, Michael O’Kane’s liquor store in a Catholic area on the outskirts of the city, was held up for the fifty-third time in the last ten years. O’Kane said he has a hard time getting help because of the holdups, and ruefully wondered if he should apply to the Guinness Book of World Records. That same week, Ruby Johnson, who owns a sweet shop on the Shankhill Road, was twice burgled, the twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth break-ins since the troubles began. She suggested that she might close shop.

Mita Dean, a Catholic confectioner on the Falls Road, did just that three years ago. “I had eight break-ins in six months,” she says, “The first time, I lost 200 in cigarettes. So I started takin’ all my cigarettes home every night. I still lost over a thousand pounds, and that hurts when you’re small, when you’re on your own. You can’t get insured because of the troubles. If someone has seen three people do it, you can get compensation, but if they burgled you in the middle of the night, who’s going to see it?”

“I don’t miss it at all now, ” she says. “I loved it in peacetime, but once the troubles started, you go down in the morning and see the door open, everything on the floor in pieces, and it breaks your heart.”

©1980 John Conroy

John Conroy is spending his fellowship year reporting on the “Social and Economic Consequences of the War in Northern Ireland.”