Story by Andrew Meier with photos by Jacqueline Mia Foster

You’ve won the war, now win the peace.” The words come to me from an old hand in the tangled politics of the Caucasus. We are sitting in a well-appointed foreign embassy in the capitol of Armenia. My host, a western diplomat, related his prescription for Armenia’s ailments. “This is what we must tell the Armenians all the time now. The war’s over, you’ve given the Azeris a good licking, but still there is no peace. What then have you really won?”

Stepanakert is the capitol of Nagorno-Karabakh, the disputed Armenian enclave that was within neighboring Azerbaijan on the old Soviet map. The victors of the oldest war in the former Soviet Union are at last rebuilding. After eight years of fighting for independence – first from Soviet control, then from Azerbaijan – a 1994 cease-fire is holding, and the leaders of the self-proclaimed “Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh” are patching Stepanakert’s shell-ravaged apartments and paving the craters in its roads.

You cannot miss the signs of renewal – a new children’s park here, an neon-lit café there. There is an urgent push to build normality. But the repairmen have yet to come to Begzadyan Street. On this stony road that runs between a cemetery and a steep ravine, life has not lived up to its prewar promises. The crumbling houses that line this tattered hillside are neither the largest nor the most handsome in town. Those belong to the “Commanders,” the victors in the war for Karabakh. Most of the homes on this street, during the seven decades of Soviet power, belonged to the Azeris.

“Seventy percent were theirs,” says Ashot, 27, as we walked beside the cemetery. In Karabakh, people often speak in percentages. “In Soviet times,” they will say, their autonomous region – measuring just 30 by 60 miles, with a population of no more than 200,000 – was “twenty-five percent Azeri.” It is the arithmetic of division.

“In those days we got along fine with them.” He has fought more battles than most career soldiers in their lifetime. “We played together, we went to school together, some of us even dated their girls and they dated ours.”

But in the waning years of the U.S.S.R., something happened. “Everybody grew up. I went off to serve in the Soviet Army, and when I came back, the talk had already started. There had been pogroms against Armenians in Sumgait and Baku. The Turks started to tell us they’d come for us next. They tried to put us down, keep us in our place. And we just wanted to be free, to rule ourselves. Judge for yourself, but I think we showed them who we are.”

In response to the 1988 attacks on Armenians in Azerbaijan, attacks on Azeris in Armenia followed. The demonstrations in Yerevan and Stepanakert grew bigger and more feverish. The Armenian hunger for an independent Karabagh only increased. By the spring of 1991, with a handful of childhood friends, Ashot became one of the first in Stepanakert to form a guerrilla brigade.

I noticed Ashot favoring his right leg. He had been thrice wounded. He lost a leg, he said, tapping the wood under his pant leg. That was the last wound, I presumed. “No,” he said, correcting my underestimation of Karabakh valor, “that was the first one.”

Today Ashot survives on a meager pension, and his family of seven lives in three windowless rooms. He suffers from his war memories. “When we first took to the hills to fight,” he tells me over shots of home-distilled vodka, “there were eight of us together from this street. Now there’s only two left.”

“But,” as we look through the dead neighborhood boys in his yellowing photographs, “if we hadn’t fought, today you wouldn’t have found even one Armenian here.”

The struggle for Karabakh began in 1988, the first of the little wars to break out in the Soviet Union as the empire cracked. Today, as in most of the post-Soviet conflicts, there is no war in Karabakh, but also no peace. No state – including Armenia – has recognized the Karabakh government. Having trounced the Azeris and wiped the countryside of any traces of their former habitation, the Karabakh Armenians now rule themselves. They have a president, parliament, constitution and most important, their own army.

They get generous help – fuel, funding, arms and recruits – from their big brothers in Armenia. In recent months, however, the fraternal bonds are wearing.

“The Karabakhis have to understand that we cannot fight for Karabakh forever,” an Armenian official tells me. “We must take care of Armenia first and foremost. We must open normal trade routes, we must develop ties to our neighbors. The more nationalistic members of this government will not agree with me, let alone the Armenian Diaspora, but we cannot play the Karabakh card forever.”

To ease the economic blockade imposed by Azerbaijan, Armenia is trading with Iran. Armenian President Levon Ter-Petrosyan, some observers note, at times enjoys better relations with Turkey than with Karabakh.

There’s a clear distinction between “Armenian Armenians” and “Karabakhi Armenians.” The Karabakhis are like second cousins. They are a remote, mountain people with the self-reliance and paranoia that isolation breeds. As the altitude rises, the vernacular turns to a dialect of Armenian, with Russian blended in.

In the Armenian capitol of Yerevan, there is a feeling that the Karabakh conflict is a national albatross.

“They went too far,” an Armenian journalist tells me, glancing over his shoulder, looking for government owls he says follow him. “The Karabakhis may have made a fatal mistake,” he says. “They took Ter-Petrosyan and all the nationalist-patriots at the word, thinking they’d fight for Karabakh forever.”

It is not merely a matter of an economic blockade, says the journalist. “It’s about Armenia’s need to clear its conscience.”

During the worst years of the war, from 1992 to 1994, the Armenian forces in Karabakh put ethnic cleansing into practice long before the Republika Srpska put the phrase into common parlance in Western capitols.

“Armenia will never develop into a truly democratic society,” predicts Mikhail Danilyan, one of the last Armenian human rights advocates still in Yerevan, “until we face the crimes committed in Karabakh.”

To the Armenians, Nagorno Karabakh, was first known as “Artsakh” in the 4th century. It is the tortured heart of their Arcadia, a lost kingdom that stretched from the Caspian sea to the Mediterranean. It became known as “The Mountainous Black Garden” for its sacred fruits. (“Kara” is Turkish for “black,” “bakh” is Persian for “garden,” while “nagorny” is Russian for “mountainous.”)

Karabakh fell to Arab, Turkic, Mongol, Persian, Russian control. In 1923, thanks to the gerrymandering genius of Josef Stalin, the overlords were Azeri. However, throughout the centuries, it remained vital to Armenians. Mount Ararat, the beacon of Armenia’s past glory, still dominates Yerevan’s horizon, but it is Turkish now – humiliatingly close, yet across the border.

Karabakh attracted Western headlines during the worst of the fighting, when an estimated 15,000 died and more than a million became refugees. These days, the region is quiet and sees few foreign reporters. But in the Russian press and the volatile politics of the Caucasus, it remains hot. Few in Moscow can tolerate the Karabakh solution, a legal limbo that permits de facto secession by force.

Last year in Moscow, rumors circulated of a Dayton II confab to resolve the Karabakh question. In May, Strobe Talbot whirlwinded through the region – stopping off in Baku and Yerevan for a few hours. Evgeny Primakov, the Russian foreign minister, followed up with more success: the exchange, with the help of the Red Cross, of 109 POW’s between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Not since Russia brokered a cease-fire in May 1994 had Karabakh garnered such attention. For nearly two years, the Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), via a multinational forum nicknamed the “Minsk Group,” has struggled to cajole Armenia, Azerbaijan and the Karabakhis into signing an agreement to end the conflict.

In December 1994, the OSCE came close, voting to commit its first peace-keeping force of 3,000 to the region. But the Karabakh leadership rejected the deal, demanding full autonomy from Azerbaijan.

“The Azeris offered us ‘cultural autonomy’ in a ‘broad sense’,” said Arkady Gukasyan, Karabakh’s foreign minister and representative at the talks. “We already have a sufficiently broad autonomy. Why should we give it up?”

In Yerevan, the official talk is more diplomatic. “We still have hopes that the framework agreement will be signed,” says Vardan Ozganyan, Armenia’s deputy foreign minister. “But our hopes are not strong.”

The Minsk Group may have run its course. “There’s been scores of conclaves, in nearly every European capitol,” a Western diplomat in Yerevan says. “And yet they’ve accomplished absolutely nothing.”

However, direct talks, long a secret never disclosed in the local press, are continuing between Vafa Guluzade and Jirair Liparidyan, chief aides to the presidents of Azerbaijan and Armenia. After they last met in Paris in November, both sides expressed unusual optimism, but produced no settlement.

The chief issues of contention remain the status of Karabakh and the six prov-inces beyond the region’s Soviet borders that are occupied by the Karabakh army. The Azeris demand the return of the towns of Lachin and Shushi. Lachin, an Azeri town, lies along the primary artery linking Karabakh to Armenia. Shushi – Shusha, to the Azeris – is an ancient seat of Azeri culture that sits atop a slate mountain, just six miles from Stepanakert. Given its elevated artillery sites and impenetrable geography, it is the most strategic fortress in Karabakh. Until May 1992, when the Karabakh forces seized it, Shushi had served as the primary Azeri citadel in Karabakh, from which they rained Soviet-made Grad missiles on Stepanakert for months.

The high-level talks may continue, but Karabakh held a presidential election in November, and has settled into a closed military state. Robert Kocharyan may nominally be President, but the strongest nationalism comes from Samvel Babayan, the 31-year-old “Defense Minister,” and real Commander of Karabakh.

“Why should we give up the occupied territories?,” he asked me with a steely glare. “Give me one example in the history of the world when a nation, after winning a war of independence, had to capitulate?”

Babayan is the youngest general in the former Soviet Union. He was an indisputable hero of Karabakh’s partisan war, even earning an extended stay in a Baku torture chamber during “Operation Ring,” the 1991 Azeri crackdown on underground paramilitary groups.

The road from Yerevan to Karabakh, winding through the slopes of the so-called “Lachin Corridor,” a thin wedge of Azeri territory that once separated Karabakh from Armenia, takes a good eight hours to cover. These days the drive through Lachin is getting shorter; the road is becoming the best highway in Armenia. Armenian money from America, Brazil, Argentina and France is paving the way back to Artsakh. Bulldozers are widening treacherous curves. Along the way, signs announce the road’s benefactors. This includes Hollywood mogul Kirk Kerkorian, a road worker relates.

The border along the road is manned by two lonely guards sitting in a converted cargo container. Last summer, they dispensed with any customs’ formalities. Unofficially, Armenia has annexed Karabakh.

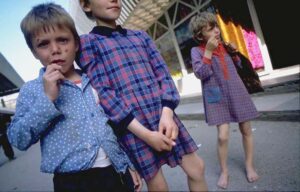

No visitor can doubt the military prowess of the Karabakh warriors, but what they have won? Electricity is a luxury, plumbing rarer. The children and elders of Begzadyan Street walk six times daily half a mile to collect water from a creekside spout.

Armenian refugees from Azerbaijan have been invited to resettle in Karabakh, and not all are happy. “They told us come to Shushi and you will find everything – an apartment, work, and shops,” said Nanar, a widowed teacher who moved here two years ago from Azeri territory bordering Iran within Armenia. “But there’s nothing here, except the ruins. We’ve been given nothing. No one here can make ends meet.”

If the residents of the Karabakh capitol face hardships, fewer still in Shushi have electricity or running water. There is no reconstruction, save for the new roof on the towering Armenian Orthodox cathedral in the center of town. In the last two years, the resettled-refugee population of Shushi has fallen by half, to 3,000.

In Stepanakert, construction crews are working. Most wear military uniforms, and are dedicated to Babayan’s army – a force that Western and Russian analysts say numbers no more than 10,000 men. This fall, a dozen new “military towns” – concrete clusters of barracks and materiel depots – are nearing completion. Draftees are required to serve two years, but the Karabakh army comprises at least 30% paid contract soldiers.

The defense bill is adding up. So, in the pastoral regions of Karabakh, brigades of pensioners are tearing out withered vineyards to plow the fields for next year’s wheat. “Bread is now worth more than wine,” one laborer, a 73-year-old ex-Communist, remarks.

A siege mentality of paranoia pervades Karabakh. The Babayan and his compatriots have fits of anti-American fury. “We know all about the U.S. advisors training Azeri pilots in Baku,” he says. “It doesn’t bother us. We’ll take on all of NATO if we have to.” Babayan claims his army is stocking up – purchasing 500 tanks, and jets, though none were at the airport outside Stepanakert. The commanders will insist they have a secret air base, but Western analysts in the Caucasus say they have only a half dozen helicopters, donated by the Armenians.

“We’re ready for the Muslims,” declares the flinty-eyed commander in Agdam, Colonel Vitaly Balasanyan. “And the next time they come, we’ll chase them all the way back to Baku and into the Caspian.”

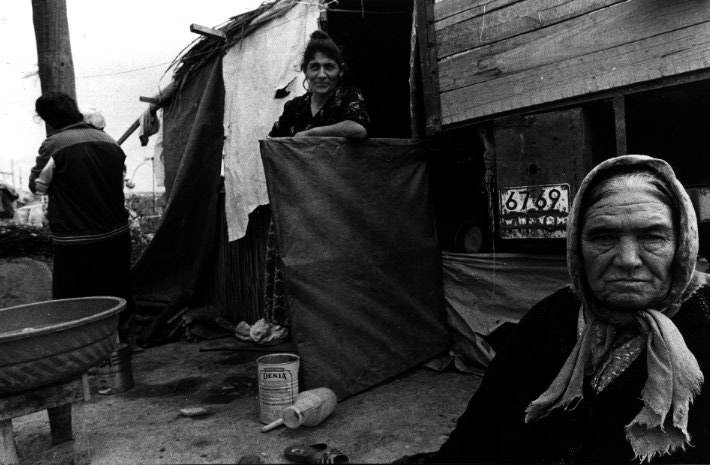

The Azeris, with troubles on their home front have scant interest in re-igniting the war. Even if the 73-year-old strong man in Baku, President Heidar Aliev, wished to regain the land lost to the Armenians, few in the Azeri government believe he could afford it. In Azerbaijan, 750,000 refugees – according to the Red Cross – remain homeless, jobless and facing their fourth winter without a foreseeable future.

Azerbaijan, thanks to the maneuvering of the Armenian-American lobby, is the sole former Soviet republic that does not receive one cent of U.S. aid. Armenia is the only republic that has a Congressional caucus on Capitol Hill. The 1992 Freedom Support Act (governing U.S. aid to the ex-U.S.S.R.) bans any aid to Azerbaijan until the blockade of Armenia is lifted.

However, the economic noose around Armenia has loosened. Yerevan now boasts new supermarkets, European sports cars and an active night-life with clubs and casinos. The blockade is porous. Trade with neighboring Georgia, Russia and Iran, is booming. In October, even the border with Turkey opened a crack, as Armenia made tentative steps toward trade. Gasoline remains in short supply and electricity is available, thanks to the recent reopening of the Soviet-built Medzamor nuclear plant. Baku’s promise of petroleum riches remains mired in a crippled economy.

The ban on American aid has not helped. Although the Azeris have signed on to NATO’s Partnership For Peace, and American corporations have invested millions in oil exploration in the Caspian, the U.S. government has only given humanitarian aid indirectly – through private non-profits – for a total $90 million since 1993. Armenia, meanwhile, is slated to receive $95 million in FY 1997 alone, if the foreign aid bill before Congress passes intact. (U.S. aid to Russia, for comparison’s sake, should near $120 million for FY 97.)

“Our hands are tied,” an American diplomat in Baku relates. “We can’t even give money for textbooks. Diplomatically, it puts us in a tough spot. Especially when politicians who’ve never even been to Baku start talking about ‘Turks’ and ‘genocide.'”

The “genocide” alluded to is the 1915 slaughter of Armenians in Turkey, when as many as a million were killed. The “Turks,” however, are not the kind in Istanbul, but the Azeris. The “politician” is Congressman John Porter, Republican of Illinois, from a well-to-do suburb of Chicago. Porter, the co-chair of the Armenian caucus, has sponsored an amendment tying any U.S. aid to Azerbaijan to funds for Karabakh, at a 7:1 ratio.

In the halls of Azeri officialdom, to call the Porter Amendment controversial is to risk verbal assault. “It stinks of the Cold War,” barked the Azeri Foreign Minister, Hassan Hassanov.

Foreign Minister Hassanov insists that “time is on our side,” alluding to the growing litany of complaints in Karabakh. But the deluge of refugees has overwhelmed President Aliev’s ailing economy. In Baku, Sumgait, Sabirabad and in a string of camps along the Azeri border with Iran, there are thousands of families who have fled not only Karabakh – where they comprised more than a third of the prewar population – but the Azeri territories to the west, south and east that the Karabakh army has occupied since the spring of 1992. Everywhere in Azerbaijan are residents of once burgeoning Azeri centers of culture and commerce. Today are defoliated and depopulated outposts for the defenders of Karabakh.

The town of Fizuli is a city in southwestern Azerbaijan seized by the Karabakh forces in March 1992, in their march into Azeri territory. Fizuli resembles the ruins of Banja Luka, Kigali or Grozny. Here, too, the populace has learned the meaning of “ethnic cleansing” the hard way.

Seen from above, Karabakh must resemble a black and green checkerboard. Its craggy landscape shows the cleansing method that guided the Karabakh forces: the green (untouched, bustling) villages are home to Armenians; the blackened (burnt out, vacated) ones are where “the Turks” once lived.

“You can see how the Soviets tried to control us,” a “guide” on special assignment from Commander Babayan explains one hard-boiled afternoon. “They deliberately mixed us in with the Azeris.”

Fizuli, once a provincial crossroads for farmers and merchants named after a famous Azeri poet, is one of several towns leveled in the Armenian Ansluss beyond the Soviet bounds of Karabakh. The crime of the Azeris who lived here was making a home on land the Karabakh forces needed as a bargaining chip.

Their military prowess and Armenia’s helping hand gave the Karabakhis a virtual sovereignty. Yet they hunger for international recognition and respect.

“We realize it’s asking too much to have two Armenian seats in the U.N.,” allows the field marshal of Karabakh’s foreign policy Gukasyan.

“One day we may have to give up the Azeri territories,” concedes Alexander Agasaryan, the Karabakh national security chief, head of its rechristened KGB. “But first we must know what we’ll get in return.”

Babayan’s commander in the bucolic district of Martouni, is Colonel Movses Akapyan. At 31, short and balding, he is charged with guarding a critical stretch of the front line. The bumps in the horizon a quarter mile east of here are Azeri border posts, manned by snipers. An Afghan vet, Colonel Movses has been fighting since he was 17. The years have built a brazen confidence.

“This was the only region never taken by the Azeris,” he says. “Although the worst battles were fought here.” Martouni is also where Monte Melkonian, an Armenian-American mercenary, led a crack brigade, grew into a Karabakh legend and died in the summer of 1993. Monte was buried in his Visalia, California home, but his death-site is a shrine, a granite statue of him was erected on Martouni’s main square (machine gun and bandoleer forever adorning his chest) and the district was renamed in his honor.

These days Monte’s battlefields are being tilled.

“Don’t be fooled,” the Colonel says. “The war still goes on. The question is not solved – and until it is, we will fight.”

At one post, a mound of dirt marks the new grave of a teenager who fell victim in the July twilight to an Azeri sniper.

The parties to the conflict often relate Karabakh to Israel. There are points of similarity: the survival of an ancient people, an embattled homeland for a far-flung Diaspora, a small territory surrounded by neighbors of a different creed, and young fighters of proven prowess. Yet an equally apt analogy might be Myanmar.

Karabakh chieftains fear an open society and a free press. The minders here try to restrict your movements by overwhelming you with hospitality. They offer you food and drink and Internet access. But they do not permit photography or poking around in places like Fizuli.

“Why do you need to see Fizuli?” became the refrain of the military guides. At last, after a series of alternating excuses – military exercises, mines, road repairs, tanks on the road -General Babayan’s boys acquiesced, escorting us down to Fizuli. Every home had been reduced to scorched plaster. No people braved the desolate streets, save the stray Karabakh soldiers who foraged for scrap metal and unpicked figs.

But on a distant street, flames climbed skyward, consuming the last homes still standing. The fires, more than two years after the last battles, are still burning.

We understood why no one in this unrecognized, ethnically-cleansed, military state was keen to have foreign reporters tour their conquered lands.

Desecration was not, of course, the exclusive domain of the Karabakhis or the Armenians from the mainland. The journey from Karabakh to Azerbaijan – impossible on land – forces a reporter into the uncomfortable role of bearing particularly bad news. Refugees have received few visitors who have seen the remains of their homes.

“If you have been,” a retired teacher pleads in Sumgait, “tell me are my cows still there?” Like most of the Azeris who fled, he left four years ago hoping to return soon. “I put out enough food for the cows and goats to last a few days.”

Ruben Karapatyan is an Armenian sociologist, a professor at Yerevan’s Institute of Archeology and Ethnography. The war has made him a self-described “conflictologist.”

“You have to study the Armenian mentality to find the roots of this fighting,” he said. “We have suffered from a victim syndrome throughout our existencethe war in Karabakh had to do with freedom and independence and for some extremist nuts, maybe even with the superiority of Christianity, but for most of us it was about breaking this victim syndrome.”

The professor explains how he watched his colleagues – physicists, historians, sociologists and linguists – take up arms. “I did not fight, but I also felt the surge of strength and nationalist pride. I, too, joined the crowds on the square and raised my fist for a free Karabakh.”

The war, the Professor notes, has cost Armenia dearly, in lost lives, in a stunted economy, and in a prolonged detour from democracy.

“But it cannot be dismissed as a mistake,” he said. “Karabakh still may not be ‘independent’ and it is hardly thriving. But now, for the first time in our lives, maybe even in the history of our people, we no longer feel like helpless victims. “

It’s impossible for you Americans to understand our conflict,” Ashot’s father, Sergei, the patriarch of Begzadyan Street in Stepanakert, tells me over an impromptu open-air feast at their home. Three generations of Karabakhis are gathered beneath a starry night.

“Our roots go deep in this land,” he says. “My father built this house. And we were raised in it knowing we’re one of the world’s original peoples. This is our pride and our strength. Did we always hate the Turks? Of course not. But this story goes far back, well before our time. It’s stronger than all of us.” By now, Sergei is crying. And these are not tears of vodka.

“All I have in the world are my boys. What would I do without them? I did my duty to give them up to the battle. But when my eldest became a fighter in the underground, the Azeris came and said they were hunting for him, that they’d cut his head off. These were my friends, my neighbors.”

In the new world disorder, “ancient hatreds” – from Bosnia to Rwanda – are blamed. But travelling among the victims and victors of this war, the religious and ethnic differences do not seem insurmountable. The more likely obstacle is politics.

To be sure, religious attacks have dominated the conflict. The iconography of Christian warriors remains visible, with crosses etched on the stocks of Kalashnikovs, painted on old Soviet tanks and drawn with bullets in the dirt of soldiers’ graves. The Azeris painted crescent moons on their tanks. These signs marked the teams. While the Armenians are deeply religious, the Azeris are not the world’s most observant Moslems. Few mosques function and few young Azeris attend madrassahs or pray five times daily. Over the decades of Moscow’s rule, both the Armenian and Azeri traditions in Karabakh were diluted by Soviet culture.

In the waning years of Soviet power, the Karabakh conflict was driven by the impulse for power and independence -first from Moscow, then Baku and now, from anyone who questions the Karabakh way. Along the way, thousands became caught in the post-Soviet politics in the Caucasus.

The Karabakh posturing has its obvious contra-dictions. Soldiers have a hard time avoiding the inconvenient truth that their purified Christian state is fed and clothed thanks to Iranian and Turkish imports. The irony is obvious. The trucks arrive daily bearing Teheran license plates. Above their windshields, aluminum tablets announce “Allah Is With Us.”

Most Karabakhis know this limbo cannot last. Leaders concede they will have to return trophies like Adgam, Fizuli and Jebrail to the hated Turks. Lachin is another matter, for Armenian refugees are settling there – with a government lure of two goats and a cow per family – to secure a vital gateway to the motherland. But Azeri lands to the east and south, now in ruins and useless for anything except diplomatic bartering, are likely to be traded.

When, and at what cost, remains uncertain. The hardened Colonel Movses in Martouni dangled a clue: “Let’s just say we’re learning capitalism – isn’t it always best to buy low and sell high?”

©1997 Andrew Meier

Andrew Meier, a correspondent with Time magazine in Moscow, is researching the Soviet Republics.