By Andrew Meier with photos by Mia Foster

SUKHUMI — One afternoon not long ago in the beleaguered capital of Abkhazia, a tiny self-proclaimed republic on the Black Sea, its reigning satrap, Vladislav Ardzinba, paced his spartan office, nervously awaiting a call from Moscow. On his untidy oak desk, amidst Soviet maps and tomes on medieval Abkhaz history, sat a satellite telephone. Since the spring, when Abkhazia’s long distance lines were cut, satellites became the sole bridges to the world beyond its narrow borders. When the call finally came, half a year late, the news was good. In the Kremlin, Boris Yeltsin had at last stirred. “Bring me Ardzinba,” he instructed an aide, “…it’s time to settle this thing.”

If the Soviet Union had a tropics, it was Abkhazia. With its palm-lined seashore and aqua-marine waters, it was the beloved summer destination of the Soviet elite, a Black Sea Malibu for Lenin’s heirs. In those days, the province fell within the borders of the Soviet republic of Georgia. No longer. A civil war that tore through its lush hills for thirteen months, from 1992 to 1993, took care of that. Today, Abkhazia stands alone — entirely. Thanks to an economic blockade, and frequent appearances of mines and bandits along its roads, tourists no longer come down to Abkhazia. These days, makeshift ministers squat in its Politburo dachas, its beaches are bare and its harbors as boatless as Havana Bay.

The Abkhaz war didn’t get much play in the West. In the first post-Soviet years, it was just one of the unlovely little wars that spread along the southern edge of the old empire. Ignited when a secessionist surge mixed with a nationalist instinct, the conflict took more than 10,000 lives, and forced some 250,000 — mostly ethnic Georgians — to flee their homes. The war, of course, deserved greater notice. If not for the numbers felled here, then at least as a precedent for the secessionist struggle that followed on the far side of the Caucasus range, in Chechnya. For in Abkhazia first emerged many of the same forces that later debuted on the world’s front-pages during the Chechen war. “Abkhazia,” says ‘President’ Ardzinba, a historian who languished in a Moscow institute for 20 years before rising on the nationalist tide, “was the rehearsal for Chechnya.”

In the late 1980s, as centrifugal forces tore at the seams of the USSR, Abkhazia was among the first ethnic vassalages to cry for freedom. Ardzinba demands that the world recognize his “suffering state,” but no one has. “Please don’t call us ‘separatists,’” he pleads. “We are an ancient people, and this has always been our land.” The Abkhaz not only have a two-thousand year history, but long memories of bloody neighborly relations. The land has oft changed hands, and faiths. Christianized in the 6th century, Abkhazia fell to Greek colonists, and later to Roman, Byzantine and Persian imperial desires, before Russia moved in the 19th century. During the war, the wire reports depicted it as a struggle between Muslim Abkhazia and Christian Georgia. True, under Turkish rule from the 15th to the 19th century, many converted to Islam. But the Russians soon brought Orthodoxy. Today, although the Abkhaz language is Turkic, crucifixes are common and there isn’t a mosque in sight.

The historical evidence, however, on the question of autonomy versus unity with Georgia is sufficiently contradictory to serve both sides. Abkhazia did enjoy a brief independence after the Bolshevik Revolution. In 1921, Lenin created the “Soviet Socialist Republic of Abkhazia.”

It lasted 9 months. A decade later, Stalin folded Abkhazia into Georgia as an “autonomous republic” — in name only. And so it stayed until the perestroika years, when the first urges of secessionism arose, and were soon followed by warfare. “We won the war,” Ardzinba fumes. “We won…our independence. Why can’t the West see that? Are they so blinded by their love of…him?” “Him” — the Unmentionable in Abkhazia — is Eduard Shevardnadze, Georgia’s president and the man once hailed as the co-architect of perestroika when he served as Mikhail Gorbachev’s foreign minister. Today, Shevardnadze almost single-handedly holds together his homeland, and in Western capitals, he remains a living reliquary of the new world order that somehow never came to pass. He and his “Western friends” are favored targets of Ardzinba’s enmity. “Mr. Shevardnadze and Mr. Clinton will rue their decision to flout international law. We will not give up,” he promises.

History has yet to decide whether the war in Abkhazia was an insurrection or emancipation. Here, as in Tajikistan, Karabakh, Moldova and Chechnya, the end of empire brought the return of bloodshed. Fighting broke out in August 1992, when Georgian troops stormed north to the capital Sukhumi to quash the surging independence movement. At the time, given the province’s rich ethnic veining, Abkhaz comprised fewer than a quarter of the population. (Georgians dominated the last Soviet census with 44%; Abkhaz, Armenians and Greeks comprised the chief minorities.) However, mercenaries rushed to their defense from across the north Caucasus: Russians, Cossacks, Dagestanis, and most prodigiously, Chechens. In Abkhazia the hero of Grozny, rebel commander Shamil Basayev, first gained fame. His brigade even adopted the name, “The Abkhaz Battalion.” With Russian hardware and air support — Moscow’s MiGs regularly flew bombing sorties during the war — Sukhumi could claim victory by the fall of 1993. Now, however, the triumph is hard to see.

“We won’t sacrifice our victory to diplomatic courtesies,” vows Ardzinba, in the cocksure cadences of a ruler vested in blood. The braggadocio affords him relief from the defiled vista outside. Few places in the former Soviet Union can compete with the darkness of the Abkhaz landscape. If more than half a million lived here before the war, less than 200,000 — by most diplomats’ estimates — remain. The land is cut off, stagnant, hungry. Georgia has won sanctions against what Shevardnadze insists is a “breakaway region.” Blockaded, the Abkhaz have had a hard time traveling, let alone trading. Geography strengthens the embargo: lodged between the Caucasus and the Black Sea, Abkhazia is bounded by the river Pso to the north and the Inguri to the south. Only a trickle of elderly men and women can cross the Inguri, walking past Russian peace-keeping posts to trade vegetables for bread in the Georgian city of Zugdidi. For young Abkhaz men “independence” has brought a virtual prison sentence. Fearing terrorism and smuggling, neither Russia nor Georgia will grant them passage. Sukhumi’s airport is idle, its railroad wrecked. And since April, when Georgia impatiently severed inter-city communications, the phonelines end at the border. (Thus Ardzinba relies on his ‘sat-phone’ — “donated,” he explains, “by friends in Turkey, Moscow, Chechnya.”)

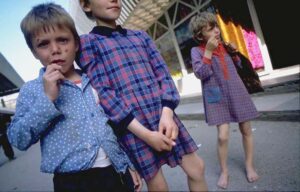

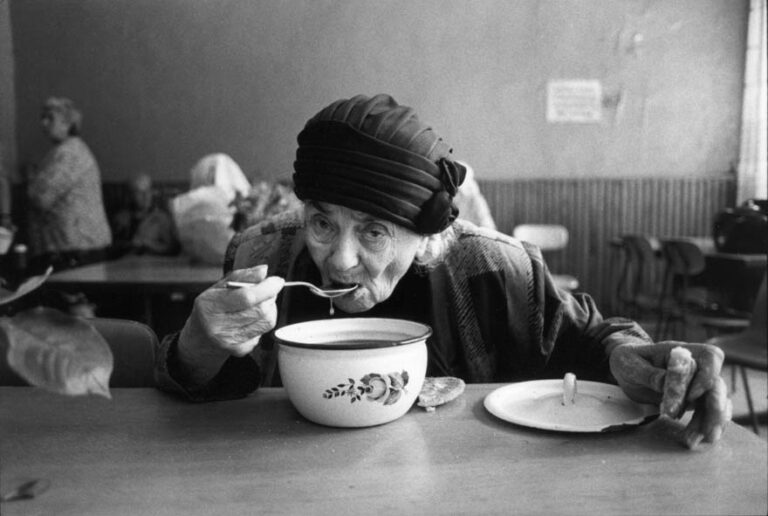

Tbilisi, meanwhile, abounds in the signs of recovery. The elegant 19th century Italianate buildings on Rustaveli street torched or shelled in Georgia’s post-Soviet cycle of coups and counter-coups have been rebuilt or leveled from sight. Georgia may still lack trustworthy electricity and telephones, but life in Tbilisi moves forward. Reconstruction of its medieval churches is underway, cafes are again crowded, stores well-stocked. Inflation is down, and growth way up. There is a future. In Abkhazia, meanwhile, the toll of the recent turmoil weighs heavily on the present. “What are we to do?” asks a young woman selling cigarettes in Sukhumi. “We’re barricaded on all sides. We have no work. How can we survive?” By dusk, as residents are quick to warn visitors, it is not safe to venture out. Anti-personnel mines, set by Georgian partisans or local jackals acting on their behalf, explode with regularity. Sukhumi’s downtown, once framed by pastel hostelries and eucalyptus-lined esplanades, now resembles the rubble of Kabul. City blocks, crushed by Soviet GRAD rockets, stand empty, abandoned. The national museum, looted and torched, is no more. Gone too are the national archives, turned to ash. Scarred busts of esteemed scholars and poets litter the oleander parks. Once an epicurean sanctuary in the Soviet age, Sukhumi now boasts soup kitchens, 16 in all, run by the Red Cross. Each day the canteens feed thousands of pensioners — mostly stranded Russians and Armenians who would otherwise spend their monthly pension on bread.

But there are other survivors still suffering. Hundreds of thousands of Georgians who fled Abkhazia four years ago, emptying entire villages overnight, still camp out in Georgia. Hotels and dormitories in Tbilisi and Zugdidi overflow with refugees, now pawns in the political bargaining. Shevardnadze, goaded by a rabid opposition to resettle the refugees, has oft declared his openness to using force to retake the Gali region in southern Abkhazia, the prewar home of nearly all the refugees. “If we must, we will move to ensure their return,” he told me earlier, shortly after Georgia paraded tanks, rockets and some 5,000 troops through Tbilisi on Independence Day.

With Tbilisi flexing its little muscles, Sukhumi has pumped up its rhetoric. “We’re a nation of fighters, not cowards feeding on Western patrons,” Ardzinba says. (He is mute, however, on the question of Moscow’s patronage of Abkhazia.) But behind the banter, the two sides have met more than once in recent months, holding secret talks. Tbilisi has offered Sukhumi “maximum autonomy” within a federation, but Ardzinba insists on “equal status.” “Federation, confederation, union…whatever you want to call it,” he says, “but we must be equal.” It is hard to fault Ardzinba’s intent. Few wish to be kept like aboriginals in a game preserve of Soviet design. Yet he may be able to boast of the accessories of sovereignty — a flag, hymn, coat of arms, stamps even — but none of the benefits. Tbilisi, meanwhile, baits Ardzinba with economic rewards, while coaxing Russia into collusion. In 1995, Shevardnadze signed a pact with Yeltsin allowing Russia to keep its bases in Georgia. In return, Russia was to shore up Georgia’s shambolic armed forces and help shepherd the refugees back to Abkhazia. This summer Yeltsin vowed that Russia would withdraw its peacekeepers as soon as a peace deal was reached. “We do not intend to keep peace-keepers in Abkhazia for a long time,” he said. “We wish that everything there will be solved in a quiet and peaceful way, that Georgia will be a single united state, but that at the same time there’ll be a large degree of independence for Abkhazia.” However, Russia has not delivered on its end of the deal, neither offering Solomonic counsel, nor bringing its boys home.

In recent weeks, the tense stalemate has shown signs of breaking. “We have reached a turning-point,” Shevardnadze says. “We cannot tolerate things as they are any longer.” On both sides of the Inguri, farmers who have seen their fields of grapes and tea go brown, call these days decisive. So, too, do the young and hungry Russian soldiers who patrol a 20-mile security zone spanning the Inguri — and who have seen 42 of their number killed in guerrilla attacks since 1994. The hope is shared by another forlorn contingent: the U.N. military observers — 126 unarmed and uniformed sitting ducks. “We’re clay pigeons,” concedes their commanding officer, a gentle Bangladeshi general seconded to the unit’s headquarters, a Soviet resort built in honor of the 15th Party Congress. Shortly after his arrival, the general discovered how far Abkhazia has devolved into a grim carnival. On a reconnaissance drive in the mountains, his land rover was ambushed. The masked gunmen spared the general’s life, but not his satellite phone. “Military observers,” muses a Danish officer, “sounds like a paradox.” Abkhaz and Georgian officials would agree, but the mission is not about to decamp.

The hope that “this year will be decisive” resounds from Sukhumi to Tbilisi. There is good reason, if only material ones, for peace. Oil and gas from the vast reserves of the Caspian Sea and Central Asia will soon course through Georgia to a Black Sea outlet — in a new pipeline that will skirt Russia. Not surprisingly, when Shevardnadze visited Washington last summer, President Clinton supported his call to broaden the peace process. What is at stake? Sovereignty, dignity and a 20th century standard of living, for the Abkhaz. For the Georgians, it’s a matter of pride and economic development. Georgian officials complain that Russia’s peacekeepers are enforcing an artificial border, ensuring Abkhazia’s de facto independence. A national security advisor to Shevardnadze recites the party line: “How can we let our country be divided under the guise of peacekeeping?” Answering his own question, he declares, “The Russians must go.”

In August, Ardzinba accepted Yeltsin’s call and flew to Moscow. But Shevardnadze, more eager than ever to enlarge the talks beyond the Kremlin, failed to show. Instead, he summoned Ardzinba to Tbilisi for a historic tete-a-tete. In only their third meeting in five years, the two sketched out a deal, but failed to sign a settlement. Shevardnadze claims the key to peace is an international peace-keeping contingent with, he hopes, U.S. participation. “If we had genuine peace-keepers,” he argues, “our refugees could go home.” However, an unpublished U.N. census claims that most of the displaced have already returned. “It’s sort of an ugly secret,” says a U.N. aid worker, “but 72% of the Georgians from Gali have gone back…on their own.” As Gia Tarkhan-Mouravi, a leading observer of Georgian politics, explains, “All the talk about status is ridiculous. It’s demographics that count. Quite simply, for Ardzinba, it’s a problem of too few Abkhaz.” At the same time, Georgian officials — who watched the West fret over Bosnia — are fond of lecturing on “ethnic cleansing.” Abkhaz leaders echo the charge, only shifting the ethnicity of those “cleansed.” For years, the verbal jousting has filled the post-war vacuum with enmity. Despite the hints of compromise, in Sukhumi the sat-phone again sits, waiting for a decisive ring.

“We are in contact more and more,” Shevardnadze reports. “We can talk,” counters Ardzinba, “but Yeltsin must act.” Ardzinba talks enviously of the peace pact his friends in Chechnya sealed with Russia last May — which put off the question of sovereignty for five years. “If it’s good enough for Moscow, why not Tbilisi?” he asks. Shevardnadze rejects the Chechen accommodation as “incomparable,” but concedes that Russia holds the key to a settlement. “The tragedy of Abkhazia was largely related to Russia. Thousands of Russians fought in the war. We would never have seen war in Chechnya, if not for the war in Abkhazia.” In an era of bound homelands yearning for liberation, Abkhazia foretold the horrors to visit the far side of the Caucasus in Chechnya. No one heeded the warning. Russia played the Abkhaz conflict masterly, in a post-Soviet updating of the classic game of divide and conquer. Now Ardzinba and Shevardnadze are left to wait for Moscow to clear its debt. For the status quo, both concede, cannot hold.

©1998 Andrew Meier

Andrew Meier, a correspondent with Time magazine in Moscow, has been examining the fate of the former Soviet republics.