Question: Which of these activities involves Head Start?

- A woman sets as her goal obtaining a commercial bus driver's license, succeeds, and then aims at a new target- taking the test for her high school equivalency diploma.

- A child sees commitment to service in adults around him and ultimately decides to join the Peace Corps.

- A woman who had dropped out of school in the eighth grade nonetheless has a yearning for more education, earns a high school diploma, then completes bachelor's and master's degrees.

- A family can't pay its rent or buy food because someone got sick and there was no health insurance. They call a federally-financed community services program seeking help.

- Thirty-six families move into new two- and three-bedroom apartments on the edge of a university town.

- Twin girls have their height and weight checked and wince as they have blood drawn so that it can be tested for lead and iron levels.

The answer, in Lee County, Alabama, is “all of the above.”

The Alabama Council on Human Relations (ACHR) is a private, non-profit agency that runs two Head Start centers serving some 350 children in Opelika and Auburn in one of the state’s easternmost counties. But it does more than prepare children for school. In Lee County, the Head Start staff has learned that when one of its families is homeless or hungry, or parents are jobless or unschooled, Head Start itself must try to address the problem rather than pass it off to a state or local government agency. They do so because of the philosophy of program director Nancy Spears and – by now – everybody who works with her: “You cannot talk to a poor family until they have food in their mouths, housing and aren’t worried about other things. Then you can say, ‘Okay, now your kid needs a good education.'”

When Head Start was gearing up for its first summer program in 1965, federal planners sought agencies that would run integrated centers. Many southern officials weren’t interested on that basis, so ACHR was asked to step in. Spears operated the program out of her basement and then astounded her bosses at ACHR by proposing that the agency keep running Head Start.

After that first summer, Spears saw that Head Start had been only that, just a start toward all the services poor families needed. “They needed much, much more,” she said, so she wrote a proposal for a federal grant for follow-through action. “They gave me a grant, believe it or not, and we went into the homes, helping families with food stamps, even though their kids were not in class” for Head Start at that point. Spears still tackles every situation with creativity, regularly applying for new programs that will help Head Start families.

Head Start emphasizes involving parents, and none got more involved than Frankie King. A tall, handsomely dressed African-American woman of 59, King was shy in those early days. When Spears first hired her as a clerk-typist although she admittedly “couldn’t type a lick,” she was hesitant even to answer the office telephone. Spears would leave the room so that King would be forced to answer it.

King had dropped out of school in the eighth grade. “I was dumb as grits when I got married, and my father told my husband that my idea of cleaning was shoving stuff under the bed.” King worked as a maid, however, cleaning other people’s homes, from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. so that she could be home when her six children returned from school. She had promised her father that she would finish her education but had no idea how she’d do it.

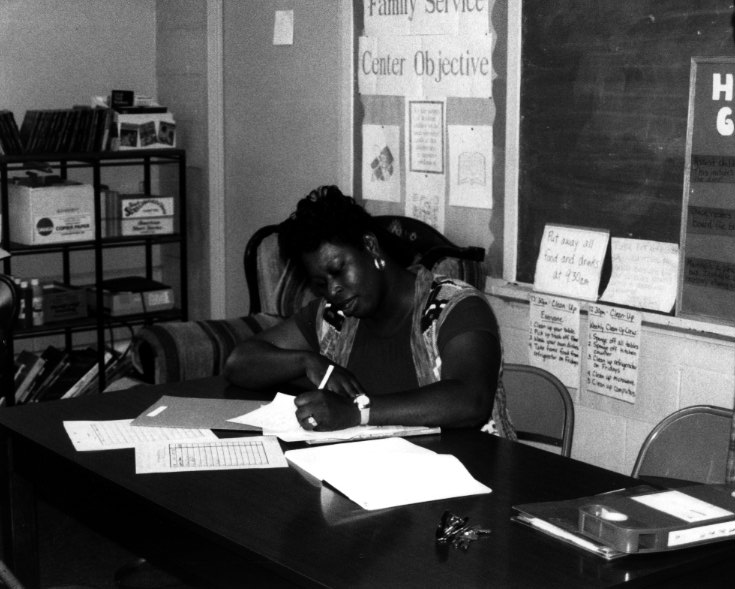

She started to work for Head Start in the fall of 1965 and soon discovered that if you were a teacher, you could get money for education. She attended classes from 6 to 8 p.m. four nights a week for 18 months and earned her high school equivalency diploma. Head Start helped her fulfill her promise to her father and her own dream. King earned a bachelor’s degree from Shaw University and in 1994 got a master’s degree from Alabama A&M. She is now ACHR’s human services coordinator.

Frankie King and her husband, who worked for the produce department of the Winn-Dixie grocery store for 34 years, instilled that love of education in their children, all six of whom are college graduates. Several hold advanced degrees. One son, Tim, runs a Head Start center in Baltimore.

Another, Stephen, attended Head Start its first full year. In 1990 he told a congressional committee: “I am a believer in Head Start because I remember it as an enterprise in which blacks and whites overcame much of the racial conflict. In very segregated Auburn, Alabama, blacks and whites could work and learn togetherI thought of it as normal that people from various cultural groups could be colleagues and friends.”

Seeing the commitment to public service of his mother and her Head Start colleagues influenced Stephen King’s decision to join the Peace Corps. He served three years in Morocco, met his wife there, and is now completing a doctoral degree in Middle Eastern politics.

Lee County, in which Spears, King and the others on the council staff operate the only two Head Start centers, had 87,146 residents in 1990, 25,000 of them in rural areas. The population then was one-fourth non-white. Although the unemployment rate was comparatively low at 5.2% (in 1994), many of the blue-collar jobs are in non-union mills or service jobs at Auburn University, and thus low paying. Seasonal layoffs are common for at least one of the county’s large employers. The Alabama Kids Count report showed that almost 20% of Lee County’s children 18 or under lived in poverty in 1990 and 21.6% of its children lived in single-parent families, which almost invariably have lower incomes than two-parent families.

“It is amazing that poor people survive in Lee County,” one ACHR report said. “AFDC payments, if one can get them, are woefully inadequate. There is no public feeding facility (soup kitchen), and food stamps are difficult to get.” To try to combat this indifference, the council started a hunger coalition that not only serves people who are hungry but lobbies for those who want to see hunger end; a child-care feeding program that enables family and group day care homes to obtain federal money and nutrition advice for providing breakfast, lunch, snacks and sometimes even supper for several hundred children a day; a newly renovated shelter – called Our House – with four bedrooms upstairs and two small apartments downstairs; and a day care center for infants and toddlers. In 1995 Spears applied for (but this time did not receive) a grant for Head Start for children under three.

The Opelika Head Start center, like its counterpart in Auburn, is housed in a building that was once the community’s all-black school. It had closed when new consolidated and integrated schools were built. Until ACHR remodeled this building for Head Start, its programs were scattered at area churches and other smaller sites. Spears brought them under one roof to eliminate duplication of services and cut maintenance costs. In addition to teachers and aides, most of the 13 classrooms have foster grandparents, who receive stipends under a separate federal program. They often comfort children who just may not be too happy to be in school that day, take the children to use the toilet and wash their hands for meals, and help supervise the outdoor play periods.

One of the downsides of the consolidation of Head Start sites into one large center is that direct parent involvement with children’s education in the classroom is difficult because so many families live far from the centers. They lack transportation, and the children travel by school bus. Faye Crandall, who directs ACHR’s educational program, encourages parents to talk more with their children at home and help them learn to find answers to their questions themselves rather than having their parents tell them what to do.

Last year she and the teachers she supervises started sending material – called RAGS, or Reading Activities and Growth for Success – home to help parents work with their children. One activity center on having children learn about money. “Many of the children haven’t dealt with money,” Crandall said. “Let them count your pocket change,” she would tell parents. “If you go to a store, tell them how much something costs and let them give the money to the clerk so that they see there is an exchange.” She wants parents, many of whom have little education themselves and may be unused to talking to their children, to increase their interaction with them.

Down the hall from Crandall’s office is the family services center, an outgrowth of a Republican administration initiative to improve Head Start. A nationwide pilot project, of which the ACHR program was a part, showed that the families of many Head Start children needed intensive help to improve their literacy and employability as well as to combat drug abuse and other problems.

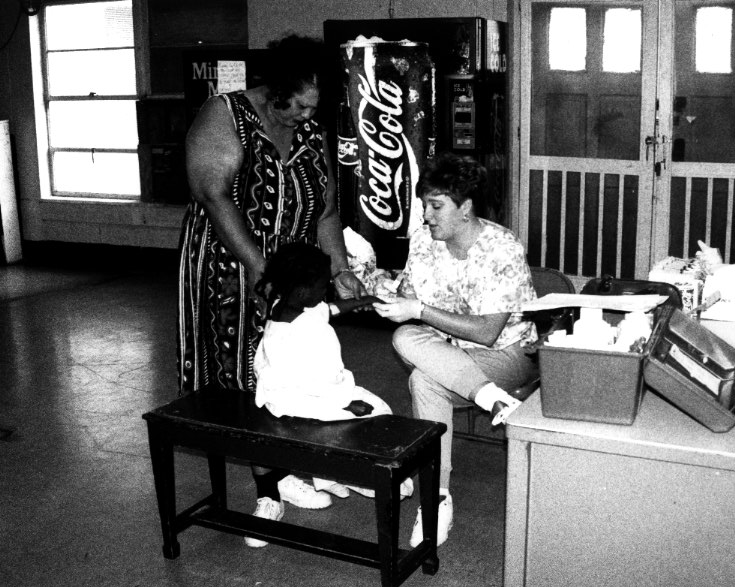

Lori Bethune, an employability specialist, was hired in January 1992 to work for the three- year family services center demonstration project, one of 40 in the country. Some of the people with whom she works have no idea how to fill out a job application, what an employer will look for in an interview, or how to behave on the job so that they can remain employed. Bethune works with them on these practical matters and also helps them set short-term and long-term goals, to look for occupations based on their values and their interests so they will be less frustrated with problems at work and more likely to stay on. Some of the people, mainly women, who have worked with her have found jobs in day care, nursing and food service.

Bethune would like to see a supportive employment program established so that she could help place people in jobs at training wages once they were ready for full-time work. Today, the jobs often aren’t there, she added.

In the past, ACHR’s staff referred Head Start parents who wanted to take classes toward their general equivalency high school diplomas to a county program. “But some of the women had topped out at third grade,” said Kay Butterfield, a literacy specialist, yet the pattern in the GED classes “was to give them a book and hope they learned. Going to class almost ended up being a punishment to get their welfare checks.” So the council started its own GED classes tailored to the women’s needs.

You cannot necessarily measure success by how many of these adults earn their high school diplomas, Butterfield said. So many people have so far to go; the reading level in her classes averages fourth grade. One-fourth of these adults read below second-grade level. Some don’t read well because they can’t see well. Butterfield noticed some of the people in her classes were holding their papers close to their eyes and moving them away or they were squinting. “All those people with low levels of reading needed glasses,” Butterfield said. “And so many of their other problems are connected with their doing poorly in school. What if their vision problems had been caught earlier?”

One of Head Start’s bus drivers, Teresa Frazier, was among the women in Lori Bethune’s class the morning I visited. She had attended Head Start herself 29 years earlier. I had heard other parents say that they had been in Head Start and now their children were. I found myself wondering, “If this is such a good program, if this is supposed to help lift people from poverty, why are people’s children following them into Head Start?” So I asked Frazier that question.

Her mother was on welfare, she told me. “People live like their mothers.” But she didn’t want to do that. She had had a job with the East Alabama Medical Clinic in Opelika but couldn’t keep it because she didn’t have her GED. She had set as one goal passing the commercial driver’s test – although she was scared about taking it – and she had done that. So she has a better job now, but she still wants that diploma. Her thirteen-year-old daughter is helping her prepare for the essay part of the GED exam, the section that intimidates her most. In short, she may still be poor but not as poor as her mother.

Janet Burns, ACHR’s administrative coordinator, said that “you don’t do 100% of the job on any family” in the time a child is in Head Start, or even in one generation. Despite the success of a Frankie King and her children, Burns added: “You just could not get every family to that point in one generation.” Twenty years ago, perhaps 60 percent of the families in the program had no one working at all. Last year Burns found that only 90 of the 387 children had parents who didn’t work. “Now we are serving the working poor,” she said. “If you could get one more generation in,” they might be able to leave poverty programs altogether.

Among the other programs that started under the council’s umbrella to help these families are a weatherization effort that has cut home heating bills and reduced energy consumption; a community services block grant that provides emergency food and housing when people lose their jobs or face other financial disasters; and construction of low-cost housing.

People want quiet, safe places to raise their children – and poor people are no different than others on that score. Students dominate rental housing in Auburn so builders have chosen to cater to their needs rather than build many apartments for low-income people, especially those with children. Spears hired Bonnie Rasmussen as housing coordinator and handed her a grant approval for ACHR to construct and co-own (with the construction firm) a $1.9 million project with a loan to be paid back to the government over 20 years. The city of Auburn helped by donating six acres of land for the 40 new two- and three-bedroom units that opened for tenants in the summer of 1995.

Shelter. Food. Child care. Job counseling. Basic education. Head Start. So what’s a program that never lacks for work doing opening a Head Start center in neighboring Russell County?

To visit Russell County, southeast of Auburn, is to step back into 1960s poverty. The statistics paint a grim enough picture: Of the 13,418 children in Russell County in 1995, almost 28 per cent lived in poverty. My abiding image of Russell County, however, lingers from a ride down a country road just outside the small town of Hurtsboro, population 770. In one yard sat abandoned cars; a pig chowed down amid children at play. Down the road an elderly black man sat in a wheelchair in the doorway of a sagging white frame house. At least he’s getting a breeze, Spears said, sadly. He had no place to go and not much of a place in which to stay. The scene could have been straight out of an exhibition of Dorothea Lange’s photographs of the Great Depression, but it’s today’s reality.

The rural area of Russell County – and it is largely a rural county – had never had Head Start. The local school superintendent didn’t care to have Head Start, Spears said. A few of the area’s black leaders and a nun who worked there urged Spears for years to go into Russell County but she wouldn’t because there were too many things undone in Lee County. “I don’t believe in taking on too much because you fail. You just can’t do all the things this program wants to do.”

Eventually ACHR won the support of a new rural school superintendent and has remodeled what used to be the black high school building in Hurtsboro. Head Start would have four classrooms for about 70 children. An adjoining wing would be a senior citizens center.

On January 16, 1996, Marian Wright Edelman, an attorney for the first Head Start programs in Mississippi in the 1960s and a strong advocate for them today as president of the Children’s Defense Fund, cut the ribbon opening the new Hurtsboro center named in her honor. The center gleamed, and Edelman and her friend and ally Nancy Spears beamed. Down the hall, little Anganique sat at a table in what the next day would become her Head Start classroom. Another chapter of the story of Head Start and the Alabama Council on Human Relations was about to begin.

©1996 Kay Mills

Kay Mills is a freelance journalist in Santa Monica, CA. writing about the Head Start program.