HARLEM, Montana – Winston Morin pulls the Head Start bus up to a pink quonset-hut classroom at the Fort Belknap Agency and joshes with teacher Barbara Long Knife as she climbs aboard for the late-morning ride. The two-way radio hanging above Morin’s left hand crackles briefly to let him know that one of the children on his route won’t need a ride this chilly morning. The bus rolls out beyond the tribe-run Kwik Stop and its gift shop onto the main road on this north central Montana Indian reservation.

The ride is my introduction to a handful of the children served by 121 Indian Head Start programs in 28 states. The 168 three-and-four-year-olds enrolled at Fort Belknap and the other Indian children nationwide make up only 4 percent of Head Start’s total, but their needs dramatically illustrate not only the impact of this federal program but also some of its problems. Indian Head Start programs also show the flexibility of a concept hurriedly put into place 30 years ago.

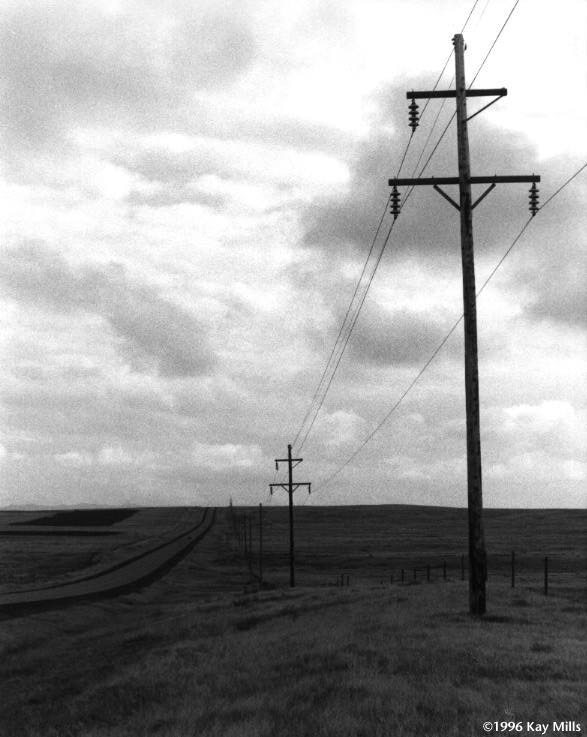

Morin drives through eight miles of virtually treeless rolling hills, spotting two antelope for me, before he picks up his first customer, a shy little girl who heads for the back of the small bus. Then we turn back north to pick up 10 more children. We’re less than an hour from the Canadian border in the vast open rangeland known as Montana’s “high line.” It’s 11:30 in the morning and at some houses both parents are home. Unemployment officially stands at about 52 percent on the reservation. Of those who do have work, 40 per cent earn less than $7,000 a year. This is not a reservation rich from oil royalties or gambling revenues.

Morin’s bus drops the children off at the recreation center where cook Panna Garrison, who has had children and grandchildren in Head Start herself, has fixed lunch. That may be the only balanced meal of the day for some. Critics may consider Head Start glorified babysitting, but Garrison disputes that notion. Not only do the children get at least one nutritious meal a day, she says, but they start learning their letters, their numbers, and their colors and “they are more sociable” with other children.

Sociability, mingling, self-confidence: whatever the words the parents and grandparents use for it, that adjustment is not to be taken lightly at a place like Fort Belknap. Some children live on such isolated farms and ranches, 40 and 50 miles from even the reservation headquarters, that they rarely get to town. When they do, they are in Harlem, Montana, population 882. It has two grain silos along the railroad tracks and a Main Street shopping area of two blocks. Occasionally, tumbleweeds outnumber pedestrians. The nearest town of any size – Havre (pronounced HAV- er), population 10,000 – is another 40 miles away.

Because of this isolation and poverty, some of Fort Belknap’s children have rarely had medical attention until they attend Head Start. The program’s health screenings catch many cases of tooth decay, poor vision or hearing, and potential learning problems, like fetal alcohol syndrome. Holly Allen-King, a guidance counselor at one of the schools on the reservation and herself a 1965 Head Start graduate, said that the screenings allow staff to work with these children before they start falling behind and failing classes.

One morning at Fort Belknap, Jari Werk’s class of four-year-olds first had breakfast of cereal, toast, milk and banana, then played with dinosaur toys and plastic building blocks while their teacher corralled them to brush their teeth. That’s a regular feature after each meal. Then the children sat at their kid-sized tables to cut out and decorate drawings of Indians. Later they paired up and walked, in mostly orderly fashion, to the gym to practice dancing for the mini-powwow that Head Start was sponsoring that week.

“Head Start helped bring back our culture,” program director Caroline Yellow Robe tells me. Government guidelines call for Head Start programs to be responsive to the culture of the people they serve, in this case the Gros Ventres and Assiniboines of Fort Belknap, plus a few white children from town. Their parents enrolled them because there is no Head Start program in Harlem.

Yellow Robe remembers the hostility toward Indian people when she was growing up, when restaurants had signs declaring: NO INDIANS OR DOGS ALLOWED. “The public schools and mission schools tried to erase our culture. When my mother and grandmother went to school, they couldn’t talk their language. They couldn’t sing their songs. They couldn’t dance their dances. They were made fun of. My people couldn’t practice their religion. The elders had to practice it at night in secret.” Head Start allowed the culture to re-emerge, she added. “We didn’t have to hide.”

As Linda Kills Crow, past president of the Indian Head Start Directors Association, put it: “We often have to teach our children they are Indian. They think that Indians are in ‘Dances With Wolves,’ but don’t realize that they, themselves, are Indian, and we try to teach pride in who we are. This is very important in our communities if we are going to preserve them.”

Many Americans may not care whether Indian children know their culture, but their parents and neighbors care deeply; several hundred showed up for the mini-powwow at Fort Belknap. Yellow Robe feels this level of involvement sets many Indian Head Start programs apart from others not on reservations. “It’s like that at all our functions,” she says. “When we have events, we have parents, community people, aunts and uncles.” Even more than programs in small towns, Head Start centers on reservations and pueblos are unique in that they are self-contained, self-defined communities. Teachers have known the families for years, and many community activities revolve around Head Start.

Parents are encouraged to volunteer in their children’s Head Start classrooms, to learn what their children should be able to do at each stage of their development and to advocate for their kids, Dawn Bishop-Moore, president of Fort Belknap’s parent policy council, says. But when they get to the public schools, it’s different. “There you have to go to the office, you can’t go to the classroom. You turn ’em over in the morning and you get ’em back in the afternoon.”

Bishop-Moore, 34, credits her own rise out of poverty to Head Start. “At a time when my second daughter was going to Head Start, I was a single mother on welfare.” Bishop-Moore attended Head Start parent meetings but always sat in the back and never said anything. “I went to the teacher of my second-oldest daughter and I told her when I was going to go to treatment because I had an alcohol problem and they held her slot open for me. I went to treatment, and I came back, I started feeling more confident in myself. I started basically moving up those rows of chairs, and pretty soon I was sitting in the front and I was voicing the things I would sit there and think about.”

Now married and the Indian parent representative on the board of the National Head Start Association, Bishop-Moore also has been named postmistress in Hays, a small town at the south end of the reservation. “I feel that Head Start has had a major role in my accomplishing that.” Her oldest daughter, the first of her children in Head Start, belonged to the National Honor Society in high school and then worked with AmeriCorps in volunteer projects on the reservation to earn a voucher toward a college education.

Years ago, Caroline Yellow Robe was a Head Start volunteer herself. She had attended an Indian boarding school in South Dakota where she was never encouraged to consider a career. “I was led to believe that the only thing I could do was go back to the reservation and raise a family.” Under the federal government’s relocation program, which placed Indians in jobs off the reservations, Yellow Robe and her first husband lived in California from 1959 to 1964. When her husband was out of work because of an operation, she picked strawberries and other crops in the Watsonville area, then moved back to Montana.

Later divorced, Yellow Robe, the mother of four, had been working as a motel maid when she first volunteered for the Head Start program in Havre in 1965. She kept working when she saw how the program helped others. “We were poor, but there were others so much poorer. I remember one family – the mother had run off and left the father with all these little kids,” she says, gesturing with her hand to show how tiny the children were. “We picked them up on the school bus – they had no shoes, no socks, and some had no underwear.”

Yellow Robe realized that education was her avenue to a better-paying job. By going to college in the morning before work and at night afterwards and attending classes every summer, she got a bachelor’s degree, then a master’s. It took her seven or eight years and there were times when Yellow Robe was frustrated. “My grades were like a graph of how I felt – up and down.”

After graduation, she taught for five years in the school at Hays on the reservation, then was named to run the Fort Belknap Head Start program in 1979. Yellow Robe, 54, a round-faced woman with a wry sense of humor and a grandma’s warmth, was honored last spring along with Rep. Maxine Waters, film director Matty Rich and six others by the National Head Start Association as the program’s “stars,” either as alumni, administrators or volunteers.

Teacher training is a major focus within Head Start, now more than ever because all its teachers must have a child-development associate (CDA) credential by September 1996. Some Indian programs, like the ones serving the Blackfeet in Browning, Montana, or the Standing Rock Sioux at Fort Yates, North Dakota, are in good shape in terms of meeting that requirement. But of Yellow Robe’s nine teachers, only one has a bachelor’s degree and two have the CDA. The rest are working toward that credential, attending satellite broadcasts on the reservation every Friday afternoon. It takes longer to earn the CDA this way, but there no longer is enough money to send teachers and teachers’ aides away to school.

“They set programs and staff up for failure without providing adequate training,” Yellow Robe laments. “Twenty years ago you could send your staff to some college for half the summer. They’d come back better prepared to go into the classroom. There was money that helped with tuition. We don’t know where it went to.”

A few years ago, all the Fort Belknap teachers had CDAs but they were either promoted into jobs as coordinators for parent involvement or health services or left for better-paying positions with public schools. No one goes to work for Head Start to make money. Yellow Robe pays her teachers with bachelor’s degrees between $9,000 and $12,000 a year and says they could make $21,000 in the public schools. Nationwide, Head Start teachers’ salaries average $16,700, up from $10,000 five years ago. Fort Belknap Head Start staff also have no health insurance; the Indian Health Service is supposed to care for them.

Indian Head Start programs – and others in rural areas – have difficulty recruiting teachers because of their remote locations and low pay. They share another problem: Head Start was set up to be run as cheaply as possible, not to pay for bricks and mortar, so its programs must buy, rent or renovate existing buildings. Until very recently, they could not build them and even now they must jump through many hoops before being allowed to undertake construction. Tribal leaders say few buildings are available on the reservation either for rent or renovation so they are forced to turn to prefabricated modular units.

The Oneida Tribe in Wisconsin received $185,000 for one such unit. “The modular is essentially four pieces of tin, and, of course, arrived unassembled,” Oneida vice chairwoman Loretta V. Metoxen told a Senate hearing last year. “The tribe had to pay (from its own funds) a contractor approximately $200,000 to ‘construct’ the modular. Then the tribe had to pay for ‘extras’ such as heating units, flooring, landscaping, fencing, sidewalks, a handicap entrance ramp, a driveway, a security system and an overhead sprinkler system.”

For the $605,000 total spent for the modular, Metoxen added, “we could have built a brand new, structurally sound, state-of-the-art facility. Instead, we have what the community calls ‘the chicken coop,”‘ which has problems with the heating, tile and linoleum, a sagging ceiling and lack of rain gutters.

Yellow Robe has her own building saga. Fort Belknap applied for money for a modular unit to serve about 22 children who live too far away to attend any of the three existing centers on the reservation. By the time Fort Belknap received approval for the money, the price of the unit had doubled. Yellow Robe could no longer afford it. Besides, the community wanted a log-kit building, which would be more in keeping with its surroundings and the tribal culture. But would a log building qualify as modular construction and thus be allowable?

Eventually, the government decided that the log building could be erected. Ground was broken last spring with help from the child whose grandfather had donated the land in hopes that the boy could attend Head Start. In the two years of negotiations, the child outgrew Head Start. He began kindergarten last fall.

Remoteness accounts for two other problems that regularly confront not only Indian but also other rural Head Start programs: attendance and the high cost of transportation. Head Start programs must maintain 85% attendance. However, the children they serve are three- and four-year-olds so they catch all the childhood diseases and are absent, sometimes because medical care is inadequate. Some of the parents live far from town – it’s 48 miles from Lodge Pole to reservation headquarters – so if they have an appointment, they take their children with them rather than send them to Head Start because they won’t be home when the youngsters return.

When snow blocks the roads in Montana or other areas with scattered population, the buses cannot get through or parents choose not to let their children go to class. Those buses cost money, an expenditure the budget writers far away in Washington don’t always understand. For example, Yellow Robe allots about 10% of her $795,000 annual budget for bus maintenance, gasoline and drivers’ salaries for vehicles to serve Head Start centers near agency headquarters, in Hays and in Lodge Pole.

Underlying these concerns is a larger one: the threat that the federal dollars will be cut drastically or that Head Start will be placed in a block grant to be administered by states. Indian programs already are tapping meager local resources to meet the law’s requirement that they find 20% of their budget as in-kind services, says Dorothy Still Smoking, who is Head Start director for the Blackfeet.

With expansion, her program in Browning, Montana, is now seeking $365,000 from its community rather than the $100,000 in services needed six years ago. “We’re looking for three times as much money, but it’s the same community. That didn’t expand.”

Budget cuts would kill Head Start for an area as poor as hers, says Yellow Robe. Without Head Start, Indian communities feel that they would lose one element that helps them unite around their children’s futures or resurrect their own lives. Whole families turn out to watch their children perform tribal dances. Dawn Bishop-Moore has a good job now. Holly Allen-King works for the school system. Panna Garrison is paying off a house and a pickup truck. Jari Werk and others take satellite classes to learn more about teaching young children. These are not isolated examples. Every Head Start director can tell similar stories.

And without Head Start, Yellow Robe says candidly, “I probably wouldn’t even be here. Where I was living, so many people have become alcoholics. I’d be six feet under from cirrhosis or whatever. That was all there was to do. You go where you feel comfortable. I went back to some of those lounges and some of the people I grew up with, they’re still there.” What her first boss at Havre’s Head Start did, Yellow Robe adds, “was give me the feeling I’d accomplish something – that my opinion counted for something.”

©1996 Kay Mills

Kay Millsis a freelancer who is examining the role of Head Start in America.