Text and photos by Jill Freedman

APF fellow Jill Freedman traveled to eastern Europe to document the remnants of Jewish life in Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia.

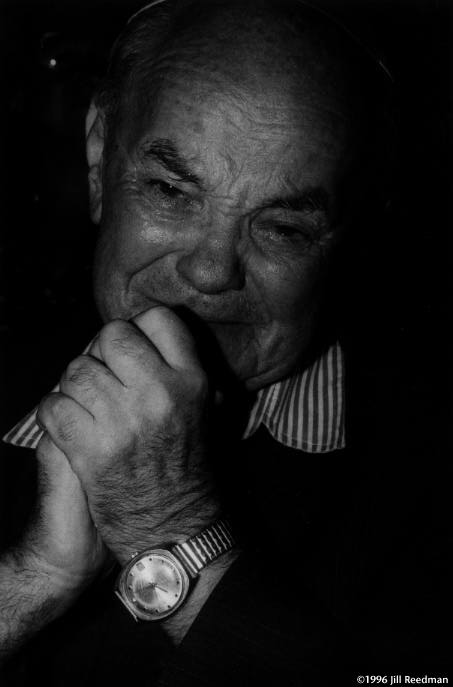

These residents of the Jewish home for the aged in Szeged, Hungary listen during a concert of the Israeli Women’s Choir in a synagogue now used for concerts. There are only 400 Jews left in Szeged, most in their 70s and 80s, and there are not enough people to support services, except on Rosh Hashonah and Yom Kippur. More than 3,000 were killed by the Nazis. On the walls of the synagogue vestibule is a poem, in Hebrew and Hungarian, found written on the clothes of a 13-year-old girl. The clothes were lying outside the gas chamber in Birkenau.

On April 19, 1941, the Nazi conference on “The final solution of the Jewish problem” was held in Prague, and soon after the first transports of Jews from Nazi-occupied countries left for ghettos and extermination camps. More than 150,000 Jews were sent to Theresienstadt, in Czechoslovakia, from 1941-45. This is its crematorium, where 30,000 Jews were burned. The ashes of 22,000 people were thrown into the nearby River Ohre.

Tourists peering into the doors of the Old/New Synagogue, the oldest synagogue north of the Alps in Europe. It’s part of the popular “Jewish Prague” tour. There are only one thousand registered Jews in Prague, most elderly. For the first time, Jewish is in, since there are virtually no Jews, just their artistic remnants. And everybody likes their art. It is strange for me to listen to German tour guides saying “Jude this” and “Jude that” and seeing German tourists walk on Jewish graves in the old cemetery.

The Jewish cemetery in Prague, which was founded in 1890. Franz Kafka is there, with his family. There’s a memorial tablet for Max Brod, and many other tablets for victims of the Holocaust. There’s also a monument, planted in 1949, in memory of the victims of Theresienstadt, erected above a grave with ashes of thousands of victims. There are many outstanding art-nouveau tombstones, and after the Nazi occupation in 1939, the cemetery was the only place Jewish children were allowed to play.

Three Polish students, part of a group called Aktion Suhnezeichen, help clean up the Jewish cemetery in Prague. The group was founded after the war by a German minister to assuage consciences. “And yet when I spoke with them, they said the richest families in Poland were Jewish, and therefore that was the reason many Poles didn’t like them’They lived like they were poor, but they had gold, silver, etc.’ Their grandparents told them about the Jews. So there you have it. Even obstensibly good kids, on the face of it, telling me that they hadn’t learned a damn thing.”

Dancers celebrate at the Joint Distribution Committee/Lauder Foundation summer camp in Szarvas, Hungary. The camp is for some 1,700 Jewish children from eastern Europe and the last week is for families. Much of the staff is Israeli and they teach Israeli songs and dances. Many Eastern European Jewish families are mixed and know little of Jewish religion or customs. Money from the Ronald S. Lauder Foundation has added a swimming pool, buildings, gym, tennis courts, classrooms, and air conditioning.

This father and son from Sarajevo were reunited at the Szarvas, Hungary summer camp after a two-year separation. The father, Albert Pesach, 68, is now a refugee in Croatia with a Bosnian passport. The son, David Pesach, 34, has a Serbian passport and cannot go to Croatia. “Who knows when we will see each other again?” said David. This is the second time his father is a refugee. His entire extended family, 30 people, was murdered by Ustashe, Croatian nationalists, during World War II.

The Jews first settled in Prague in the early 10th century. The third Jewish settlement originated in the 12th century, in the place later known as Jewish Town. From the 13th century until 1848, Jews were forced to live within a walled ghetto, cut off from the rest of the town and subject to a curfew. This was 300 years before the word “ghetto” was coined in Venice. They were made to wear, first, a yellow cloak (11th century), then in 1551, under Ferdinand I, a yellow circle, distinguishing them from Christians. The forced marking of Jews was strictly enforced and signaled bad times ahead, which were abundant.

The Jewish town (ghetto) was damaged by devastating fires in 1240, 1336, 1369, 1523, 1689, and 1754. Each time the Jews rebuilt their community. They were expelled from the city from 1543-45, 1557 (Ferdinand I), and 1745-48 (Empress Maria Theresa).

They were decimated by plague in 1348-49, 1660, 1713-14.

There were bloody pogroms all along, theft of Jewish property and Jewish life. The first pogrom was in 1096, during the first crusade. One of the worst was in 1389, when 3,000 Jews were massacred over Easter, some while sheltering in the Old-New Synagogue, which is in use today. It almost wiped them out, and the terrible anguish, hopelessness and impotence can be heard to this day in the words of a mournful elegy composed by a witness, the poet Avigdor Kara. Every year on the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur, the words of this elegy sound as a warning cry among the walls of the Old-New Synagogue. But warnings were not enough to save Prague’s Jews. The Nazis were not the first to steal and slaughter, but they were the most thorough and now there is little left to steal or murder.

©1996 Jill Freedman

Jill Freedman is a freelance photographer in Miami who examined the Holocaust.