Text and photos by Jill Freedman

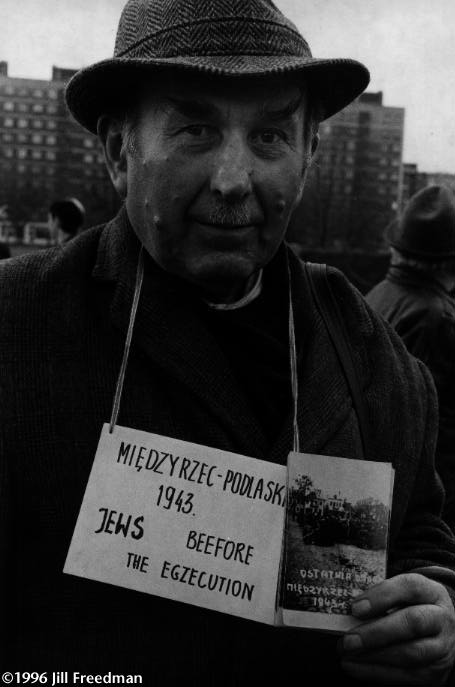

In the Lublin region of Poland, on November 2, 1943, an operation, given the code name “Harvest Festival” by the Germans, was begun. Its object was the murder of those survivors of the Warsaw ghetto uprising who had been held since April in labor camps at Poniatowa, Trawniki and elsewhere in the Lublin region.

In a few days, fifty thousand Jews were shot in ditches behind the gas-chambers of Majdanek, among them more than five thousand Jewish soldiers of the Polish army, who had been held prisoner for the previous four years in the Lipowa Street camp in Lublin. Brought to Majdanek in small groups from Lipowa Street on Nov. 2, the instinct for survival could not be crushed. Led by a former Hebrew teacher, with the surname Szosnik, the Jews broke through the armed guards shouting, “Long live freedom.” Members of the SS, Hitler and the Nazi Party’s paramilitary organization (Schutzstaffel), opened fire. Most of the prisoners were killed. According to Shmuel Krakowski’s “War of the Doomed: Jewish Armed Resistance in Poland 1942-1944,” ten were able to escape.

Other Jews from the Lipowa Street camp, also former soldiers, were taken to Majdanek and refused to the last moment to remove their army uniforms. They, too, were shot. Only one camp in the Lublin region escaped the “Harvest Festival” slaughter, that at Budzyn, whose labor was needed to operate the Heinkl aircraft works. But even at Budzyn, all elderly people were “selected” in November,1943 and taken to Majdanek. One of the Jewish cleaners in the camp, Jacob Katz, saved the lives of seven elderly Jews by hiding them under mattresses during the selection, and later smuggling in bread to them. The rest, taken to Majdanek, were shot.

Anna Hyndrakova, of Prague, smuggled photos of her mother, and sister, Trude, into the labor camps. They perished in the gas chambers, along with her father, brother-in-law and her niece. When the Nazis took over Prague in March, 1939, the Jews lost all human and civil rights. Anna was 14 when she was deported with her family to Theresienstadt in 1942, and later, Auschwitz-Birkenau.

They tattooed a number on her arm, then Anna and her mother reported for selection together, filing naked past a committee of SS-men, most of them drunk. She had just turned 16 and was selected for work. They didn’t take her mother, and her father said he wouldn’t leave her mother. She and her parents were parting forever.

“The SS-men yelled, I cried, my parents kept telling me to go but kept holding on to my hands! I shall never forget that moment. I can still see them. I didn’t know what I should do. I wanted to be with them, but I probably also wanted to live.

“For a long time I reproached myself for my decision to leave Birkenau. I felt I’d betrayed my promise to my sister that I would look after our parents. It still haunts me to this day.”

Anna had photographs of her mother, father and sister. With a pair of nail scissors, she cut out just their heads, wrapped them in cellophane and hid them in her hair under a bobby pin. She kept transferring her treasures when she was in the Women’s Camp, in the showers. Once she had them in her mouth and had to open it. ‘What’s that you’ve got in your mouth, you elephant?’ the guard said. ‘Photos’ I replied. ‘Whose?’ ‘Mom’s.’ ‘Get along then’ she said and so I smuggled them through.”

Two of those pictures are all she has left.

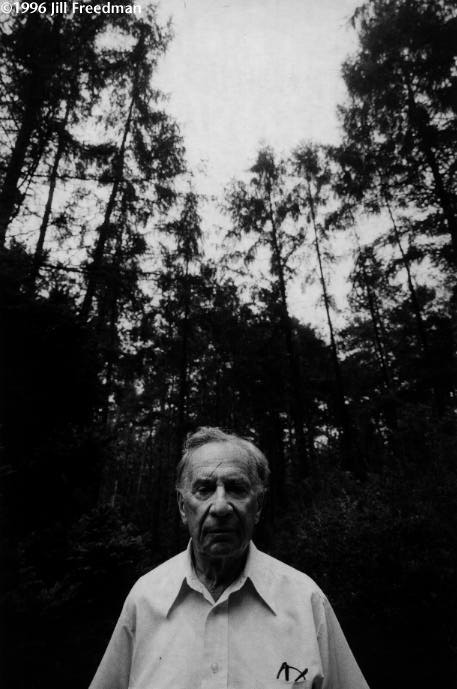

Lou Salton, founder of the Salton kitchenware company, stands in a national forest preserve ten miles from his Polish birthplace, Wieliczka. His father, grandmother, step-mother and step-sister were shot here, along with all Jews in the town. Poles dug pits and threw people in, burying many alive.

Salton left Cracow in 1940, but his grandmother refused to go, so the rest of his family stayed and were killed. His mother and sister were choked in gas vans by carbon monoxide from diesel engines. The Saurer Company of Austria supplied the vans and they killed his relatives and 580,000 other Jews in Belzec.

Salton, 82, returned to find his family’s death place. Surviving Jews had dedicated a stone to their memory. There were no signs, no paths leading to it. We found it only with the help of an old peasant. Salton stood where his father had 52 years earlier. All around us the trees were dying of pollution from Cracow and from fallout from Chernobyl.

©1996 Jill Freedman

Jill Freedman, a freelance photographer based in Miami, spent her Patterson year documenting the Holocaust, 50 years later.