Alice Salazar worries about the changes that newcomers are bringing to the Houston neighborhood her family has called home since the turn of the century when her grandparents immigrated from Mexico.

“This place is full of fly-by-night people now,” she said speaking English with a distinct Texas twang. “They’ve been dropped off by the bus and are waiting for someplace else to go. And while they’re here, they just act like they were still in Mexico, not taking care of anything, putting garbage wherever they feel like it. No wonder the place is deteriorating.”

Mrs. Salazar’s neighborhood, called Magnolia, has steadily attracted Mexican immigrants since the first docks and factories were built nearby in the 1900’s but never have so many come as in recent years. The staid blue-collar community Mrs. Salazar knew as a child has become an impoverished, bustling port of entry.

It has been a difficult adjustment for people like Mrs. Salazar. Yet despite her occasional outbursts of disparagement, Mrs. Salazar spends hours a week selling cookies and raffle tickets at a local parish school and holding community meetings in her living room so the new arrivals can get better social services.

“For the longest time I could see they needed help, but I’d turn my back because I didn’t want to have anything to do with them,” she said, “well, I’ve realized that these are our folks and we’ve got to do something for them.”

Mrs. Salazar’s disdain and her concern, her fears and affection, her resentment and her sympathy are all manifestations of an acute ambivalence towards recent immigrants increasingly common among native-born Latinos.

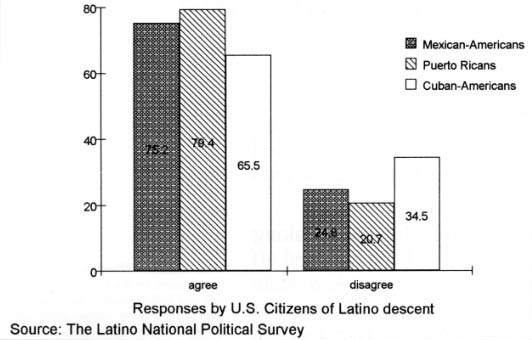

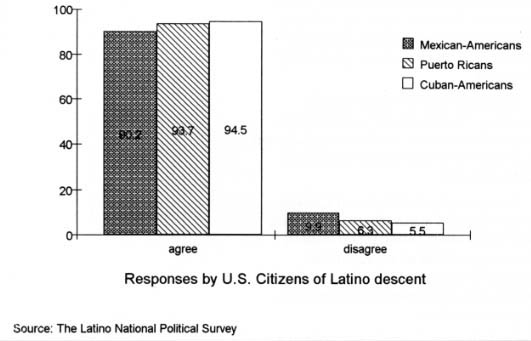

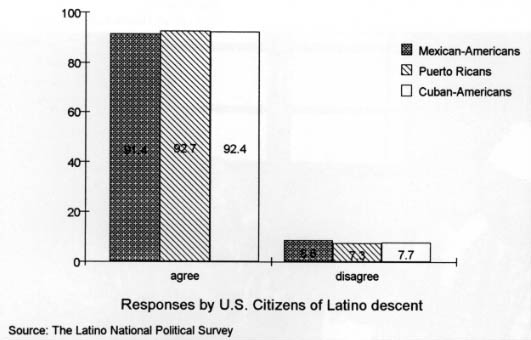

Similar sentiments emerged from the Latino National Political Survey, a major public opinion poll released last December. An overwhelming majority of the Hispanic respondent, said there was too much immigration. However, equally large majorities expressed deep allegiances to their national origins. More Latinos who are U.S. citizens preferred to be identified as “Mexican-Americans” or “Puerto Ricans” rather than think of themselves as “Hispanics” or “Latinos” or simply as “Americans.”

With the nation in the midst of the largest wave of immigration since the 1920’s it is uncertain how these painfully mixed feelings will be resolved. Latinos could become a cohesive and powerful force in American society or they might be permanently splintered into groups and sub-groups with competing interests.

Given the size, complexity and rapid growth of the Hispanic population, however, there is no doubt the outcome will have an impact far beyond places like Magnolia because relations among Latinos will shape ethnic politics in the United States well into the 21st century.

During the last great wave of immigration, ethnic solidarity played a major role in helping newcomers adjust to America. Self-help groups eased people through their financial and social problems. In their jockeying for political position the Italians, Poles, Irish and others worked to make citizens out of the new immigrants because ethnic bloc voting led to power and patronage.

Given some of the unique characteristics of the Hispanic population as well as changes in the nation’s economy and its political system, it is unlikely those patterns will repeat themselves precisely.

Unlike any other major segment of the American population, Latinos share a common linguistic heritage but otherwise make up an assortment of classes, races, cultures and national origin groups. And, they are split between immigrants and indigenous Latino groups, primarily Mexican-Americans and Puerto Ricans.

In the 1980’s the overall Hispanic population increased by 53 percent to 22.4 million in the 1990 census, a growth rate five times the national average. But at the same time the number of immigrants from Spanish-speaking countries grew almost twice as fast, nearly doubling in the census figures from 4.4 million in 1980 to 8.5 million in 1990.

“Our numbers as Latinos may be going up but that’s not getting us any place as divided as we are,” said Victor Lopez, mayor of Orange Cove, California and a veteran politician in the San Joaquin Valley.

The signs of these divisions are everywhere, he noted. Longtime Mexican residents become visibly annoyed when recently arrived Salvadoran immigrants take on public roles, like reading scripture in church. Mexican farm workers often encounter the harshest treatment from Mexican-American crew bosses. Gang fights between immigrant and native born Latinos are more common than those between Latinos and other ethnic groups.

“As long as we are our own worst enemies, we’ll remain poor and powerless,” he said, “and if we are powerless, then it’s no surprise that immigrants don’t become citizens and citizens don’t vote and the whole thing perpetuates itself.”

This year could prove a turning point for the complex internal dynamics of Latino communities. Starting in October some 2.5 million people who gained permanent resident status under the 1986 amnesty for illegal aliens will become eligible for citizenship. How many take the opportunity, and how much encouragement they get from native born Latinos will color the social and political complexion of places like Magnolia and Orange Cove for years to come.

“Some people argue that naturalizing all these people from the amnesty, could become an occasion of ethnic solidarity,” said Rodolfo O. de la Garza, a professor of government at the University of Texas at Austin. “It could just as easily bring out the open class rivalries and other differences that have been simmering for years.”

Economic frictions undoubtedly increased during the recent recession especially because the downturn followed a decade of record immigration from Latin America.

For example, the late Cesar Chavez, of the United Farm workers of America, and many other Latino union leaders have argued that an overabundant supply of immigrant labor has undercut wages and undermined their ability to organize workers.

Paul Aleman, business manager of a construction laborers’ local in San Diego, said, “we’ve lost whole segments of the industry, like landscape construction, to non-union immigrants, and there’s no way we’ll ever get those jobs back given the wages they’ll work for.”

Yet Mr. Aleman clearly reflects the divided feelings common among many Latinos. “Sure, it upsets me,” he said, “but most of us in this local are Mexican-Americans or Mexican immigrants”.

So, we’re torn. We feel for these people. Besides that, we ask ourselves who created the problem. Was it the people who came across looking for jobs or the contractors who hired them?”

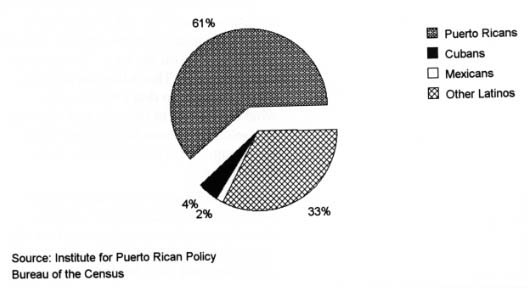

Another factor producing divisions in the Hispanic ranks is the ever greater diversity of national groups making up the Latino population as a result of immigration. Persons of Mexican and Puerto Rican origins, the two largest groups by far, still make up more than 70 percent of the Latino population, but the number of immigrants from El Salvador nearly quadrupled during [be 1980’s and those from (be Dominican Republic and Columbia doubled.

These tensions reflect a major difference between European immigration in the first halt of the century and the growing Hispanic population today. Nearly two-thirds of all Latinos are native born Americans, and many of them feel little connection to the immigrant experience. Indeed, many see no advantage in being associated with immigrants.

Ben Benavides, president of the California chapter of the Mexican-American Political Association, grows visibly angry discussing the subject.

“We’ve been here fighting the discrimination, getting very oppressed since the beginning,” he said, “and now you see these Salvadorans coming right in and demanding everything they want, and you know, a lot of times the Anglos would rather deal with them than with us.”

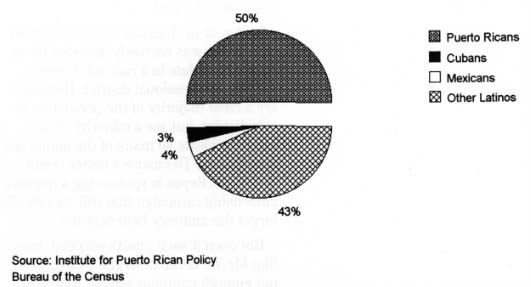

In New York City, Puerto Ricans once held an exclusive franchise on Latino politics but the growing Dominican population has begun to assert itself quite independently, electing its first representative to the City Council, Guillermo Linares, in 1991.

“A lot of Puerto Ricans feel that they are fading from view, and that Dominican concerns are taking the spotlight,” said Angelo Falcon, director of the Institute for Puerto Rican Policy. “That leads to tensions, even hostilities. It is not at the stage of all out war but we have to work on it because none of us can afford more fragmentation.”

The dangers of this economic and political competition in an increasingly diverse Hispanic population were laid bare during the Los Angeles riots last year.

Once the looting began, television pictures showed that many Latinos joined at least this part of the disturbances. The immediate assumption in many quarters was that these were primarily immigrants. Traditional Mexican-American neighborhoods like East IA)s Angeles remained peaceful while most of the violence occurred in Pico Union and South Central, neighborhoods that have acquired Hispanic populations relatively recently. The impression was reinforced when Los Angeles police began sending many of the Latinos arrested in the disturbances to the Immigration and Naturalization Service for possible deportation.

During the riots several local black political leaders, such as Rep. Maxine Waters, made highly visible efforts to restore calm. There was no similar effort from the most prominent local Latino officials whose constituencies are centered in the Mexican-American east side. At the very moment that the largest Latino community in the nation needed leadership, it got disclaimers instead.

City Councilman Richard Alatorre was quoted in the Los Angeles Times as saying, “I try my best to be an advocate for (immigrants) concerns, but I didn’t get elected to represent them.”

And, Gloria Molina, the only Hispanic on the powerful Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, admitted to The New York Times, that she really didn’t know much about the Latinos in the riot areas. “At a time when we really needed to reach out there we found that we were not as informed as we could have been about who the Latino leaders were in that area,” she said.

One local Latino official who did go into the streets during the riots was Mike Hernandez, a recently elected and relatively unknown city councilman whose district includes Pico Union. Although he is careful not to criticize his Latino colleagues directly, he is derisive about those who claimed not to have a stake in the burned out neighborhoods.

“You know what Bo Jackson said about the Super Bowl?” he asks rhetorically and then shoots back the answer with no hint of a smile on his face. “‘Bo not in it., Bo don’t care.’ That’s the attitude of a lot of people who don’t want to see what’s going on in this city and who can find excuses for not looking real hard by saying, ‘they’re immigrants, they don’t count.”‘

With the Hispanic population in the midst of rapid demographic change, experts and activists differ over how the internal divisions of the Hispanic population will be solved.

Harry Pachon, director of the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials, believes that sheer political necessity will bond citizen and immigrant Latinos. Noting that in California, more than half of all the Latino adults are ineligible to vote because they are non-citizens, he said, “naturalizing immigrants has not been a priority in the past, but Latino leaders are now realizing that is the way to get real numbers to the ballot box.”

The beneficiaries of the 1986 amnesty soon to become eligible for citizenship represent “perhaps the best opportunity we’ve ever had to work with a large bloc of people,” he said.

Last year in Houston, city councilman Ben Reyes was narrowly defeated by an Anglo candidate in a race for a newly drawn Congressional district. Hispanics are a clear majority of the population in this district, but are a minority of the voters because so many of the adults are immigrants. To ensure a better result next year, Reyes is sponsoring a massive citizenship campaign that will specifically target the amnesty beneficiaries.

But even if such efforts succeed, some, like Mr. de ]a Garza, argue that there is not enough common ground to unify Latinos politically.

“Native born Latinos feel so culturally different from immigrants they are often embarrassed to be identified with them,” he said. “Also, they have different economic interests because they are mostly better educated and better off than the immigrants. So, there is no reason to assume they can all come together as a cohesive political force simply on ethnic grounds.”

However, F. Chris Garcia, a professor of Political Science at the University of New Mexico, believes that powerful forces outside the various Latino communities could promote greater unity.

“You have government, the media and advertising all promoting the idea of a pan-ethnic ‘Latin o’ or ‘Hispanic’ population so much that eventually it will start sinking in.” he said. “Beyond that Latinos will bond together for self protection to the extent that the core culture treats them all as a distinct ethnic minority and discriminates against them all. If there is less discrimination or Anglos learn to differentiate among Latino groups, there will be less solidarity.”

With almost half of all Latinos less than 18 years old, these dynamics are likely to resolve themselves in a process of generational change.

Pedro Pedraza, director of the Centro de Estudios Puertoriiquñeos at Hunter College, said, “Among the young you start to see a mixture of identities evolving where the national identity is strongest in some situations and a trans-national Latino identity emerges in others.”

He notes that gang fights still break out along national lines but that increasingly young Latinos all listen to each others’ music. Also, while the young preserve distinct national accents when they speak Spanish, they have the same accent and use the same slang in English.

“There is a huge generation of Latino kids, mostly citizens, raised in this country, growing up with all this immigration around them, and they will hit voting age around the turn of the century,” Mr. Pedraza said. “Then we’ll learn how this all turned out.”

©1993 Roberto Suro

Roberto Suro, the former Houston bureau chief of The New York Times, is examining Hispanic life in the U.S.