Photos and article by APF Fellow Roberto Suro

LOS ANGELES — During Los Angeles’ days of fury in spring,1992, the sounds of gun fire and helicopters reminded Elsa Flores why she had left El Salvador more than a decade earlier and made her wonder what she had accomplished by coming here.

As the rioting flared all around her home in South Central,Mrs. Flores bundled her family into a back room of their little bungalow, and from this refuge they watched the mayhem outside on television. On the second day of the disturbances she saw something familiar on the TV, and putting the helicopter shot in perspective she realized the building that housed her small clothing business was on fire.

“I watched and held my daughters,” said Mrs. Flores, who had worked nine years as a salesclerk, eventually saving enough money to put up her own stall at one of the big indoor flea markets where many immigrants do their shopping. “As it burned I held them tighter and tighter and as I watched the flames I thought, `It is all lost, all lost, everything I’ve earned in this country, all lost.'”

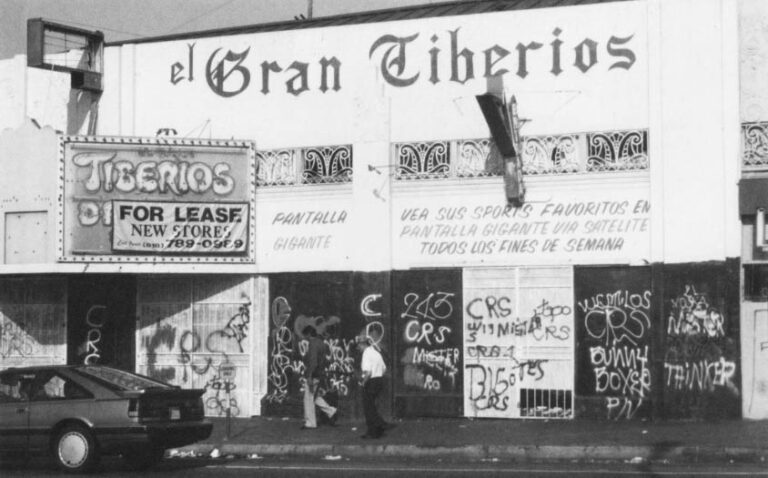

More than a year later and now loaded with debt she has opened another clothing stand in a converted movie theater, but she measures her loss in the riot in more than money. The lessons she and other Latino immigrants draw from those events will reshape the city.

“In this kind of neighborhood you have to learn to live with worry about all the crime and the drugs and the gangs, and I thought I had,” she said. “After this I don’t know. In El Salvador there is violence, but you can understand it, but here I ask myself, how can it be that in such a big and developed nation there can be so much violence.”

For her and thousands of other Latino immigrants the appeal of South Central, an overwhelmingly black neighborhood just a few years ago, was cheaper, less crowded housing than in the city’s older barrios. Now she and her husband, who has his own stall at another market, are wondering whether the inner city is such a good place to raise daughters ten and three years-old.

A small woman with broad shoulders who bargains hard with every customer, Mrs. Flores said, “I know people who have moved out to parts of the city far away, even the desert. They say it is better for hard working people. I’ve thought about it, but it is hard to think that all we are doing is so we can pick up and start over.”

Every year hundreds of thousands of new Latino immigrants pour into the nation’s inner cities. They are by far the largest single group of new entrants to the urban population, and they are learning to become Americans amid myriad urban ills. Each of them are absorbing the culture around them, adapting to it and in some cases becoming alienated from it. The outcome is far from certain.

The Los Angeles riot is often compared to the black ghetto uprisings of the 1960’s, but the chief similarity is that these events serve as a warning and the Los Angeles riot warned of new problems in a new type of city marked by massive immigration.

While the anger of blacks towards Korean store owners grabbed headlines at the time, it is now apparent that Latinos played the most complex role as both perpetrators and victims of the riot. Some 51 percent of the people arrested were Latinos as were some 30 percent of the dead, and Latinos owned up to 40 percent of the damaged businesses, according to a study by The Tomás Rivera Center.

And, Los Angeles is not the only place that Latino immigrants have expressed a kind of alienation through violence in the streets. It happened in New York City’s predominately Dominican Washington Heights neighborhood in July 1992 and in Washington D.C.’s heavily Salvadoran Mount Pleasant community in May 1991. On both occasions the police shooting of a Latino provided the spark for disturbances that lasted for days.

During the last great wave of immigration around the turn of the century, poor inner city neighborhoods served as ethnic havens where immigrant groups built-up their economic and political strength so that they could move into the American mainstream. The cities are a different place now.

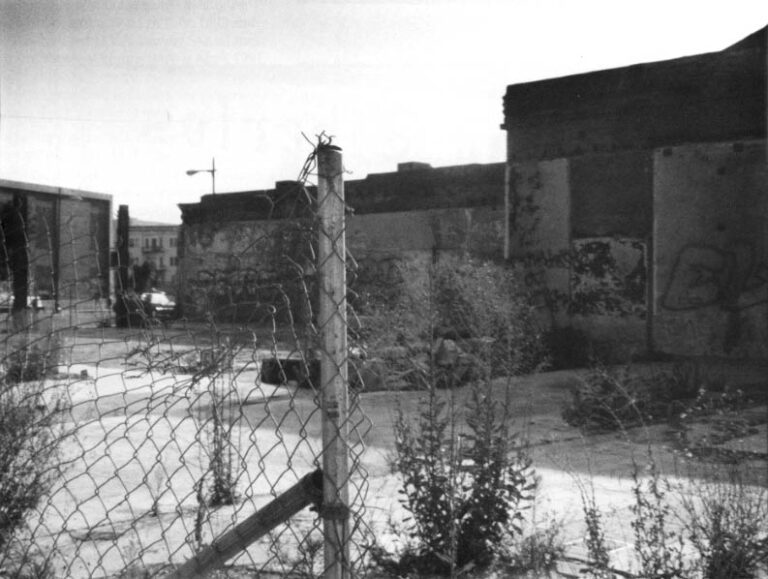

Among those who arrived in the 1960’s and 1970’s as the current wave of immigration began, many have moved up and out to the suburbs. But starting in the mid-1980’s the pace of Latino immigration accelerated rapidly with up to as many as a million newcomers a year. As in the past, the great majority went first to the urban core, but this huge group of immigrants arrived to find the American city in a profound crisis.

The crack epidemic, bankrupt local governments and a stagnant economy are making life more difficult for all city dwellers, but these problems hit the new arrivals especially hard. Even as they learn a new language and new ways, today’s immigrants must overcome obstacles that have defeated many of the native born now relegated to the urban underclass.

As this period of immigration unfolds, a key question will be how many newcomers make it out of the inner city and how many become trapped there in a life of chronic poverty.

“I call it the `East L.A. short circuit,'” said Art Revueltas, “and the way it goes is that if you come from Mexico to East L.A. and you have kids, the clock is ticking on how long you’ve got to make it out. If you get stuck, the kids don’t make it through school. So, they don’t make it out. Then, you get teenage parents and those kids won’t make it out. All of a sudden you’re talking about third generation gang members.”

Revueltas is the son of a Mexican immigrant who came to East Los Angeles, the city’s oldest and biggest barrio. About a quarter of the Latino families there live in poverty and some of the street gangs do indeed trace their lineage back more than three generations. Revueltas and his family got out. He is now the vice-principal of an intermediate school in Montebello, a Latino middle class suburb of Los Angeles.

He is deeply worried that an ever greater number of immigrants are getting short-circuited.

Looking back, Revueltas, 40 years-old, sees that the immigrants of his parents’ generation established themselves in the 1960’s when the industrial economy boomed and government mortgage programs helped assure a supply of affordable quality housing. As a result, he went to college, and his parents helped him buy a home after he graduated.

“They developed enough equity to allow me to become vested in the system,” he said.

Now, a large and often unbridgeable gap separates the working poor from the middle class, and the social dynamics of the city have become especially lethal for the young people of immigrant homes.

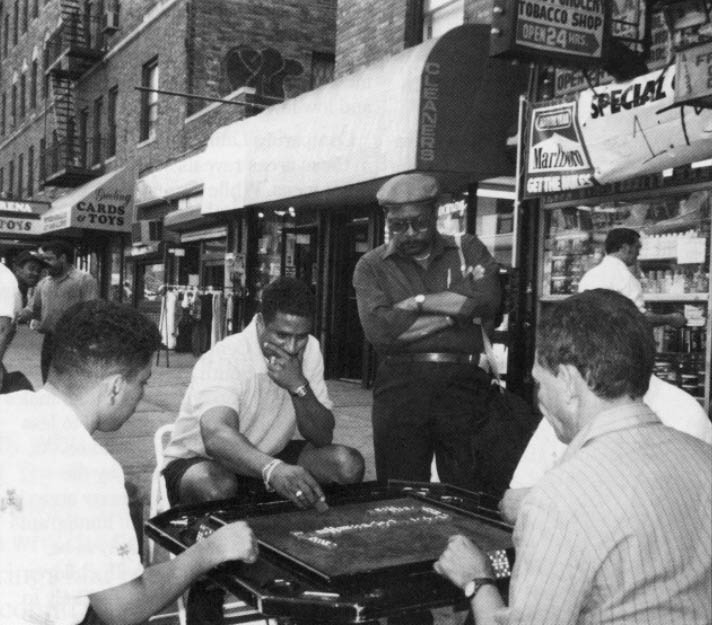

“It’s changed, it didn’t used to be this way,” said Emilio Betancourt, as the sound of gunfire echoed through the alley behind his home in East Harlem.

“There’s always been hustlers and tough guys around, but there was hardly anyone getting killed,” said Betancourt, (TK)years old, who has lived in New York’s oldest Hispanic neighborhood since he came from Puerto Rico as an infant.

“Now, there’s this bang-bang-bang every night,” he added,”and it really just started when crack arrived. The guns and the money came with crack. That happened in about 1986 around here, and it hasn’t been the same since.”

Residents of almost any inner city neighborhood can mark that grizzly event with equal precision. For people in communities that serve as ports of entry, however, the arrival of crack in the mid-1980’s has a special significance because it coincides exactly with the arrival of a massive new wave of immigrants.

Overall, immigration in the 1980’s was more than twice that of the 1960’s and the pace quickened through the decade so that immigration in the latter half of the 1980’s jumped by at least 10 percent from the first half.

These two distinct and unrelated events –crack and immigration– overlapped to deadly effect in Washington Heights.Some 50,000 new Dominican immigrants settled in the neighborhood in the last half of the 1980’s even as it became one of New York’s major cocaine trading centers.

The result is most grimly obvious in the crime statistics.From 1985 to 1990 the number of murders in New York rose by a horrifying 63 percent, but in the northern Manhattan precinct that encompasses Washington Heights there was an increase of 115 percent. And, similarly, the number of felonious assaults and total arrests rose more than twice as fast in the Dominican enclave as for the city overall.

Many recent immigrants, and many others, have found they could endure the other hardships of inner city life but have drawn the line at the increasing violence associated with the crack epidemic. The result has been an out-migration of those who are most mobile due to their education or their success in the work place.

“More and more we see some of the best people going,” said Moises Perez, director of the Alianza Dominicana, the largest social service agency in Washington Heights. “The last wave of immigrants included a lot of professionals and a lot have gone back or just moved out. After all, if you have a choice, why would you want to raise your kids with the most overcrowded schools, the most overcrowded housing and on top of that the highest crime rates in the city? No, it doesn’t make sense. If you have the option, you move out as soon as you can.”

What worries community leaders like Perez in immigrant neighborhoods around the country is that this is not the gradual, generalized movement out of the inner city that marked the overall advancement of immigrant groups in the past. Instead, it is the brusque departure of the most able, and it leaves behind those of lesser means and possibilities.

William Julius Wilson, the University of Chicago sociologist who developed the concept of the underclass, argues that the exodus of middle and working class families from black inner city neighborhoods has made the poverty there more permanent and more profound. The out-migration, he says, deprives communities of leaders, role-models, and connections to the job market as well as steady incomes to help maintain local commerce.

Replicating this experience among Latino immigrants would greatly increase the size of the underclass and would also create a new category of urban poor further separated from the mainstream by language, culture and, in many cases, by lack of legal immigration status. But, such an outcome is by no means inevitable.

A study of ethnic settlement patterns in Los Angeles by Ali Modarres, a geographer at California State University, Los Angeles, found that Latino immigrants who arrived in the 1980’s are highly concentrated in several different communities.Sometimes they are the predominate ethnic group and sometimes they cohabitate with poor blacks, whites or Asians. But, in each case these communities are marked by similar characteristics such as overcrowding, low incomes, a large number of young people and low levels of educational attainment.

Comparing Latinos to their neighbors in these areas reveals some stark differences. While a greater proportion of the Latinos live in poverty, the actual circumstances of their poverty is quite different from that of the native born. The Latinos are working poor, and they live in intact families.

The Rivera Center study, for example, found that in South Central Los Angeles more than 80 percent of the Latino males are in the labor force, compared to less than 60 percent of the non-Latinos. An extensive survey conducted by the University of Chicago of poverty areas in that city found that Mexican immigrants were more than twice as likely to be living as married couples with children than blacks and five times less likely to be single mothers with children.

The Chicago study also found that Mexican immigrants show a stronger preference for work over welfare compared to blacks and that the Latinos expressed markedly negative attitudes towards welfare recipients compared to blacks.

Even more important than these attitudes, the Chicago study found that the immigrants share distinct advantages over blacks in benefiting from tightly knit networks of friends and relatives who provide access to jobs and child care among other things. These networks amount to a powerful new “Latino civil society” in urban areas says David Hays Bautista, a UCLA sociologist, who is studying immigrants in South Central.

“They come from cultures where people have survived poverty for centuries with little recourse to government or other institutions,” he said, “and here they have very little connection to community groups or city agencies but they have established very effective linkages among themselves.”

So, after Elsa Flores lost her clothing stall during the Los Angeles riots, she didn’t even think about going to a bank or seeking reconstruction relief. “Those places always ask for a million papers and things that are impossible,” she said.Instead, she rounded up $6,000 from friends and relatives to get started again. “They know I learned how to do this from my parents,” she said.

Latino immigrants are redefining the nature of urban poverty in other ways as well. By their sheer force of numbers, they are creating new barrios far from the urban core. In some cases, this is a mark of success by Latinos who have established themselves solidly in the middle class. But, from the San Fernado Valley to the Washington beltway, there are new Latino communities marked by large numbers of recently arrived immigrants living with low incomes.

These communities are suburban in location only. They haven’t followed the traditional immigrants’ route of arriving in the central city and then migrating out as finances improve. They go right to the suburbs without the finances.

“The movement of Latinos in the 1980’s is something very different from the suburbanization of whites,” said Leo Estrada,a demographer at UCLA. For one thing, Latinos,. blacks and Asians are moving into residential areas being abandoned by whites,transforming them initially into new multi-ethnic communities although eventually one group or another becomes predominant.

And, Estrada notes, “even though Latinos are moving towards jobs in new centers of economic activity outside the urban core,they may not be very good jobs. Household incomes go up for awhile and then fall back and this seems to happen about the same time that the new communities develop an ethnic concentration.”

Just as the last great wave of immigration remade the American city in ways unpredictable when the steamships were still unloading at Ellis Island, urban America is now in the process of being reinvented again. From the fires of South Central to the emergence of suburban barrios the landscape offers signals that a process of change has begun but is still very much underway.

@1993 Roberto Suro

Roberto Suro, the former Houston bureau chief of The New York Times, is examining Hispanic life in the U.S.