Back home in Austin, Texas, Bob Kafka and Randy Jennings usually fight each other. Yet both came to Washington the same week leading delegations of Texans to lobby for passage of a civil rights bill for disabled people. They shared the same goal, but their style and tactics could hardly have been more different.

Kafka, a savvy protest veteran, brought 30 militant activists, all disabled and all members of American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit, or ADAPT. They came to disrupt Congress with protests, sit-ins and other acts of civil disobedience. Jennings and his 17 colleagues–only one of whom has a disability–are rehabilitation professionals who belong to the Texas chapter of the National Rehabilitation Association, or NRA. They had come for polite meetings with members of Congress to explain why their clients need their rights protected. At issue was the Americans with Disabilities Act, landmark legislation to extend to disabled Americans the types of guarantees against discrimination in public accommodation and employment that were granted blacks, women and ethnic minorities in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Kafka and Jennings are contemporaries, two Vietnam veterans who have devoted their lives to helping disabled people. Kafka, 44, is a paraplegic who uses a wheelchair, the result of a 1975 automobile accident. Jennings, 49, is not disabled. To Kafka, full-time activism seemed a natural calling for the grandson of Russian-Jewish immigrant labor organizers, whose work on behalf of leftist causes had brought FBI agents occasionally to their Co-op City apartment in the Bronx. “Rebel with a Cause,” says the epitaph on his grandmother’s gravestone. Kafka’s sentiments were on the sleeve of his tee shirt, which listed a half-dozen other cities that have been sites of ADAPT sit-ins since 1983. Two ADA buttons were pinned to the corduroy cap on top of his mass of curly black hair. It seemed right, too, that Jennings, a folksy, fifth-generation Texan in a suit and cowboy boots, should work getting jobs for disabled people. His grandfather, at 19, had gone off to fight on the killing fields of World War I and had come home with a hook for an arm, a glass eye, partial hearing and a crooked smile from mustard gassings. He then worked as a security guard on the San Antonio-to-Laredo train, repelling the robbery attempts by the remnants of Pancho Villa’s gang and other border bandits.

Kafka and Jennings arrived in Washington at a time when huge changes are taking place in the lives of disabled people.

Perhaps most significant is the rise of a civil rights movement around disability issues. Disabled people–whether they are blind, deaf, have mental retardation, or use wheelchairs–now see their problems as ones of rights, instead of as problems of health. Rejected is the traditional notion that it is up to a disabled person to overcome a physical or mental limitation. Instead, goes the new thinking of the disability rights movement, it is society that needs to change. The biggest obstacles are the result of society’s prejudices, be it a building inaccessible to someone in a wheelchair or an employer who refuses to hire someone with epilepsy. As a result, disabled people are demanding more control over their own lives.

The sunny week in March that Kafka and Jennings came to Washington showed that disabled people, working with the professional disability groups they have come to distrust, could successfully raise the consciousness of Congress and the nation to the countless acts of discrimination disabled people face daily in their lives.

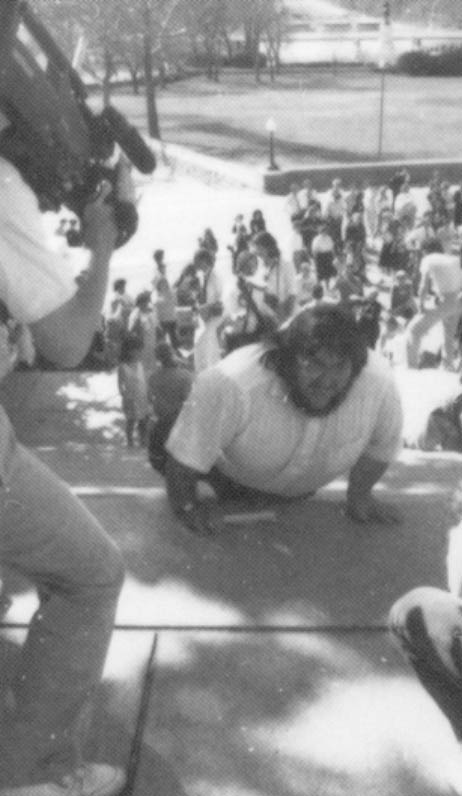

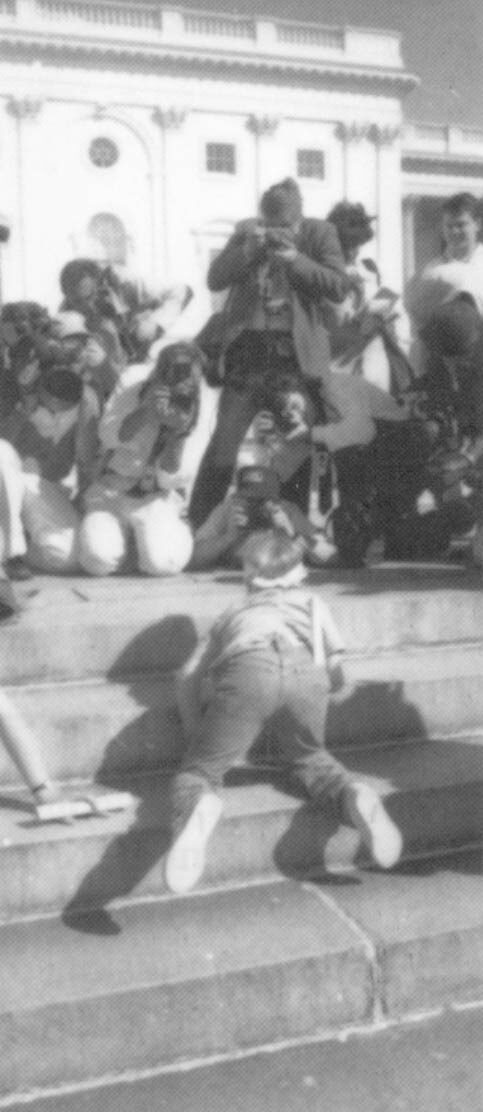

MONDAY: “The preamble to the Constitution does not say ‘We the able-bodied people.’ It says, We the People,’ ” Mike Auberger, the leader of the DAPT protest in jeans and a tee shirt with his hair in two braids down to the seat of his wheelchair, spoke to a crowd at the base of the Capitol. As the protesters chanted “Access is our civil right,” about three dozen ADAPT demonstrators threw themselves out of their wheelchairs to begin a “crawl up” of the 83 marble steps to the Capitol.

Some 475 people representing a wide array of disabilities joined ADAPT’s Wheels of Justice march from the White House to the Capitol. Another 250 people came for the rally. In the scheme of Washington protests, the number was minuscule. And yet history was being made. The rally was the largest demonstration ever by people from different disabilities. Representatives from many of the hundreds of disability interest groups–including a dozen members of the Texas NRA delegation–showed up. Unlike the fight for rights by blacks, women and homosexuals that are often pointed to by disabled people as models, the disability rights movement has never filled the streets with tens of thousands of protesters. One reason: Many disabled people find it hard to travel. At the hotel where 200 ADAPT demonstrators were based, for example, only three rooms had bathrooms accessible to wheelchairs. And because there are hundreds of different disabilities, various groups often have different agendas. Many deaf people, for example, want funding for separate schools where sign language is taught, which they say are crucial to nurturing a deaf culture. Most people with other disabilities–and even a minority of deaf people, the oralists who learn to speak and read lips–reject segregation and insist on being educated in “mainstream” schools.

How then could this largely invisible and deeply fractured movement be so strong that its far-reaching bill was gliding through Congress? Former Representative Tony Coehlo (D-Calif.), who has epilepsy, talks about a “hidden army.” More than one in seven Americans has a disability. Not surprisingly, key support for the ADA bill came from people with personal knowledge of disability and chronic illness, including President Bush, who lost a young daughter to leukemia; Senator Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), who has a deaf brother; Senator Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.) whose son lost a leg to cancer and whose sister has retardation; and Representative Steny Hoyer (D-Md.), whose wife has epilepsy.

As ADAPT activists demonstrated, seven women from the Texas NRA delegation visited a member of that “hidden army,” Rep. Steve Bartlett, a Republican from wealthy north Dallas. The conservative lawmaker had come to appreciate the efforts of disabled people to get off of welfare and into jobs. Most of the opposition to the ADA bill came from business groups, particularly small ones, worried about their liability under the new law. But even the business community’s opposition–which was fierce to civil rights legislation in 1964–was surprisingly muted. Bartlett ran a small plastics manufacturing firm before coming to Congress in 1982. Like him, many business owners see disabled Americans as a pool of potential employees in a shrinking labor market, as well as a base of new customers. From his experience, Bartlett also knows that disabled people must fight low-expectations and prejudice. He told the NRA women of a girl with Down Syndrome from Harlingen. Her parents fought to get her into classes with non-disabled peers. Yet, even then, unthinking school officials excluded her from pep rallies and refused to let her pose with her schoolmates for her class picture.

Such discrimination is a common denominator that binds people of various disabilities. Seventy-four percent of disabled Americans say they share a “common identity” with other disabled people and 45 percent argue they are “a minority group in the same sense as are blacks and Hispanics,” according to a 1985 poll by Louis Harris and Associates. Taken together, people with disabilities–numbering 43 million, according to the Library of Congress–would make up the largest minority group in the country. Also fueling the rise of a movement is a new generation of better educated and more politically active disabled people. Millions have completed school since a 1975 law that guaranteed disabled children an education.

At the end of this day, some of the activists questioned the crawl up. Mary Johnson, editor of the Disability Rag, the irreverent movement newspaper, worried that it conveyed precisely the image disabled people want to avoid–of being pitiable and child-like. Indeed, the cameras had zoomed in on 8-year-old Jennifer Keelan struggling up the steps. Yet the network news reports that night stressed exactly the message ADAPT wanted to get across: That disabled people are demanding civil rights.

TUESDAY: “I can understand that you’re frustrated,” said Representative Bob Michel, who was called in to speak to 150 ADAPT demonstrators who had taken over the rotunda of the Capitol to demand that the bill go to the House floor the next day. Atlanta activist Mark Johnson shouted down the Republican House leader: “We’re not ‘frustrated,’ we’re pissed off.” That set off a chorus of chants and yells, eventually sending Michel and House Speaker Tom Foley from the rotunda. The ADAPT members had scheduled a “tour” of the Capitol, but when they chanted and chained their wheelchairs together, the Capitol Hill police started making arrests.

ADAPT represents a growing militancy among disabled people and this was the kind of angry guerrilla theater for which it is best known. Wade Blank, the group’s non-disabled founder, a Presbyterian minister whose models are Martin Luther King, with whom he worked in Selma, and organizer Saul Alinsky, says such actions underscore, over and over, that society is set up to exclude disabled people. Today’s 104 arrests, he said, would “short-circuit the system.” Steps and narrow doors make the city’s jails inaccessible to those in wheelchairs. Other demonstrators need attendants to feed them or interpret when they speak. So Washington police would have little choice but to release the demonstrators quickly. Once free, the activists would find another target and get arrested again.

While police carried the protesters down an elevator only big enough for one wheelchair at a time, across the street in the Rayburn House Office Building the Energy and Commerce Committee was marking up the ADA bill. Tom Sheridan, a lobbyist for the AIDS Action Council, stood outside the committee room, urging lawmakers to vote against several anti-AIDS amendments. Many disability activists are envious of the public fascination with the gay rights movement. The week before ADAPT arrived, a national news weekly devoted a cover story to ACT-UP, the gay rights movement’s media-savvy version of ADAPT. But Sheridan watched in awe of the score of disability lobbyists, representing hundreds of disabilities from epilepsy to mental illness, working outside the committee room. It is because of the influence of these established groups, including the NRA, that federal and state governments will spend $60 billion on disabled people this year. People with AIDS do not have the same network of federal programs to give them such clout on Capitol Hill, Sheridan noted.

Because AIDS is a chronic disease, people with AIDS or who are HIV-positive are protected from discrimination under the ADA bill. The alliance between the disability and gay communities helped spur the bill. But that alliance worried some lawmakers. “I don’t want to hand out anything more to those damn homosexuals,” Ralph Hall, a Texas Democrat from the rural district descended from former House Speaker Sam Rayburn, told the NRA women. Gay people, Hall argued, get AIDS because, by their own choice, they engaged in risky sexual behavior. “We don’t make judgments when we help people with head injuries,” shot back Valerie Jean Schwille, who followed in her father’s footsteps to become a rehabilitation Counselor. “We don’t ask first, ‘Were you speeding in that car crash?’ Or, ‘Did you have too much to drink?’ We still help them.” Hall conceded, “You’ve got a point there.”

As the different groups in town lobbied, they debated amongst themselves: What is the most effective way to bring about change? One disability activist was distressed when Senate Republican leader Bob Dole (R-Kansas), who lost use of an arm due to a World War II injury, walked by the rotunda sit-in and said, “This doesn’t help us any.” Traditionally, non-disabled professionals like Jennings, who works for the Texas Rehabilitation Commission which gets disabled people into jobs, have run the groups that help disabled people. But now Kafka and other disabled men and women are demanding the right to make their own decisions and run their own organizations. Even well-meaning professionals, Kafka says, are too often patronizing to the people they want to serve. Jennings says Kafka and ADAPT are good at getting attention with their shouting, but lack credibility because they then refuse to sit down and negotiate. That is not ADAPT’s role, counters Kafka. ADAPT demonstrators, he says, knew they were seeking the impossible when they demanded an immediate vote on the ADA bill. The point was to force a confrontation to show that disabled people care deeply enough to go to jail for their rights.

Taking such a drastic stand, Kafka says, gives disabled people a sense of empowerment after lives of dependency. “Most people see disabled people as childlike and helpless,” says Kafka. “We’re not Jerry’s Kids. We’re not going to be passive recipients of charity anymore. We’re changing our image. We’re demanding our rights.” Such rude protest challenges widely-held expectations of disabled people to be unfailingly polite, explained activist Eleanor Smith. Exhausted after driving over 12 hours to Washington from Atlanta, she had moved her wheelchair into the elevator at her hotel Saturday night. “What floor would you like?” asked a woman in her early-30s standing near the control panel. “Three,” said Smith, who is 47. “Aren’t you forgetting your manners?” asked the woman’s husband, who added in a treacly voice, “It’s ‘three, please.’”

WEDNESDAY: The ADAPT demonstrators, off the high of their sit-in the day before, planned an even bolder action: To close down the subway system that links the Capitol to the House office buildings. But the plan went awry when four groups of demonstrators got lost in the subterranean maze of walkways under the Capitol. As he flew out onto Independence Avenue in his motorized wheelchair, Auberger cursed himself for his botched strategy and, like a Civil War general, made a mental note to “never again” diminish the group’s power by dividing into small units. The demonstrators regrouped to take over the office of Representative Bud Shuster (R-Pa.), author of an amendment to exclude sparsely populated areas from making new buses accessible. There were 59 more arrests.

One of those at Shuster’s office was a 35-year-old former financial analyst who joined ADAPT after being unable to find a job. He had successfully managed multimillion trust funds, but when the market crashed in October of 1987 he, like many in his field, was out of work. Despite his qualifications, the man, who wants his name withheld, spent months without work, briefly becoming homeless. Some potential employers told him to his face they would not hire a paraplegic–an excuse that would be against the law under the ADA bill. According to the Harris survey, 70 percent of disabled people are unemployed and of those two-thirds say they can work and want to work. Even those who do work earn only 64 percent of what their non-disabled coworkers make, according to a U.S. Census Bureau survey.

To Kafka, rehabilitation professionals, or “suits” like Jennings, are part of the problem. Rehabilitation services, such as job counseling, training and placement, were required by an act of the U.S. Congress in 1920. The NRA formed five years later. Today, rehabilitation is a $2 billion-a-year industry, funded by federal and state governments. One million people were served last year, of whom nearly a quarter found jobs. Yet despite those numbers, the system reaches only one of every 20 people who need help, according to NRA officials.

Kafka complains that rehabilitation counselors “cream”, or take on the easiest clients and do little or nothing for those who need help the most. Few of the 30 protesters Kafka brought to Washington have full-time work. Most are angry over having slipped through the cracks of the rehabilitation and welfare system. They included people like James Templeton and Victor Ramirez. Both have cerebral palsy and spent three decades of their lives in state institutions, where they were given little education and few choices, until lawyers helped them get out.

Jennings, too, wants to see more of his disabled clients working. Rehabilitation professionals are restricted by funding limits and by the law, which says only someone deemed employable can get help. The ADA bill, he says, would significantly boost the numbers he could serve by, among other things, requiring employers to make inexpensive accommodations in the workplace, like raising the height of a desk for someone in a wheelchair. The need for a bill like ADA first became apparent to Jennings years ago when he found a 19-year-old paraplegic a job in a muffler shop, but could not get him to work the next day. No city buses had lifts. The ADA bill would require them on all new buses. “This bill is the most significant piece of legislation to come along for disabled people in a long time,” says Jennings. “It’s civil rights; it’s what’s needed.”

The NRA delegates wrapped up their session and left Washington.

THURSDAY: “When I was born, I had a problem with my left arm, which was paralyzed. There were a lot of things I couldn’t do. But I didn’t break the law.” D.C. Superior Court judge Robert Scott, 68, told the ADAPT demonstrators how, despite his disability, he went on to law school, eventually being appointed to the bench by President Carter. Then he meted out punishment, some of the toughest, ADAPT leaders said, they have ever received. Scott was astounded to find out that Auberger had 25 arrests on his record. (The ADAPT leader did not mention that on an at least equal number of occasions all charges against him had been dropped.) Auberger was fined $500 and put on supervised probation for one year–in essence, putting ADAPT’s captain out of action by forcing him to avoid arrest or else be brought back to Washington to serve jail time.

Scott’s tough sentencing infuriated the ADAPT activists. Even worse, they felt Scott had slighted those who have trouble speaking by addressing questions to people next to them, instead of letting them struggle with their words. Another ADAPT leader who got a heavy fine, Stephanie Thomas, Kafka’s wife, says Scott is a familiar disabled type–one who hides his disability to “pass” in the non-disabled world. (Scott, in an interview later, noted his reputation for being a no-nonsense judge and said he treated the protesters the same as he would anyone else. “If they expect because they are in wheelchairs to flaunt what is clearly the law and not expect anything to happen,’ he said, “they’re crazy.”)

Tied up in court all day, the ADAPT activists reluctantly ruled out another action. They returned to their hotel dispirited, unsure what Friday and another day of courtroom appearances would bring.

FRIDAY: Auberger, Thomas and the three others sentenced by Scott showed up, as ordered, at the parole office–only to find there was no wheelchair ramp to the building. A court officer eventually met them outside. But Tim Cook, the group’s attorney, quickly filed a half-million dollar lawsuit against the court. A federal law requires that all government buildings be accessible. That 1973 law, amendments to the Rehabilitation Act, prohibits discrimination by any agency, institution or business that receives federal funding and is the prototype for the ADA bill. One of the strongest selling points for the ADA was that this law, pushed by rehabilitation professionals, proved such anti-discrimination measures could be effective, without being burdensomely expensive.

If the day before court proceedings had gone poorly, the remaining ADAPT members to be sentenced could hardly have been more surprised by the reception they got from judge Bruce Beaudin. It started when Arthur Campbell, who has cerebral palsy and has difficulty speaking, asked if someone could read remarks he had written out. The judge agreed. “Take this courtroom,” Campbell wrote. “We cannot use the jury box…We cannot get on the witness stand…And we can not get on to the judge’s bench.”

Beaudin was moved by Campbell’s words and soon everyone in the courtroom was speaking, telling their most personal stories of discrimination and struggle. For many it was the first time someone in authority had listened to their tales of pain. People who could not speak, like Claude Holcomb of Connecticut, slowly spelled out their statements, letter-by-letter, on boards they carried marked with the alphabet. People who rarely talked at all, out of shyness and fear, spoke with eloquence. The courtroom took on the air of both a revival meeting and a political rally. People clapped, shouted and cried.

“I’m here for Kenny,” said Christine Coughlin, a one-time Easter Seals poster child, referring to Kenny Perkins, who had died six weeks before at the age of six and who had been to eight ADAPT demonstrations. Unable to speak, the result of severe head trauma from an automobile accident when he was an infant, Kenny would blink his eyes twice to say “yes,” once for “no”. His mother Ronda was in the courtroom helping interpret when Coughlin unexpectedly mentioned her son. Startled, she broke down in quiet sobs. “I’m here for the children,” Coughlin, a college student, continued. “The children of the future who shouldn’t be told they can’t sit in a restaurant because they cause a fire hazard, and for the children who shouldn’t have to be told that they can’t ride a bus or get into a bathroom, or have adequate nursing care.”

George Roberts of Denver, who also has cerebral palsy, asked that Blank be allowed to tell his story of being abandoned by his parents “on the doorstep of an orphanage” to spend 25 lonely years in institutions and nursing homes until he got help to sue to get out.

Even Judge Beaudin was choking back tears by the time the last speaker, Wayne Spahn of Austin told his story. “When I was a baby, they wanted to put me away. But my mother and father fought and I stayed home with them,” he said. “All we want is education and jobs, good jobs, to try to get out in the community and be like everybody else.”

It ended with Beaudin praising the demonstrators. “The rightness of your cause is a big one,” he said. He imposed minimal,$10 fines. “I’m going to take a break, I can tell you that,” Beaudin said, teary now himself. And with that, the judge stepped from the bench and went around the courtroom shaking the hand of each of the activists.

Note: Returning to Texas, Kafka sparred with Jennings’ state rehabilitation agency for not giving disabled people more of a say in its new budget. On July 26, President Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act into law.

©1990 Joseph P. Shapiro

Joseph P. Shapiro, an associate editor at U.S. News & World Report, is examining the changing world of the disabled.