“One thing we’re going to vote on is a revolution!” Deep-felt cheers erupt from the convention crowd. “Resolution” is the word that T.J. Monroe wanted. But revolution, really, is more like it. Monroe and the 300 people in the hotel ballroom are retarded (a word they despise, but more on that in a moment). They are trailblazers of the self-advocacy movement, a new and spreading crusade of people with mental retardation to make their own decisions about everything from where they live to what they are called.

“You have to do two things today,” Monroe exhorts his rapt followers to open the assembly. “You have to make thunder. You have to speak for your rights.” For his listeners, just gathering at this meeting is a daring and heady act of subversion. Others have always laid out their lives for them, telling them what to do and what to think. “You’re not gonna get in no trouble speaking for yourself, because there aren’t going to be laws in this room,” Monroe reassures the audience. “I want to hear thunder!”

By the end of the day, several revolutionary resolutions will be passed with raucous joy, unanimity and plenty of thunder. Close down all state institutions for people with retardation. Give us paid sick leave, vacation time and holidays at our job sites and at sheltered workshops. Recognize our right to relationships, and that means our wish to have sex with those we choose in our institutions and group homes. And please, do not call us retarded. That is an ugly word that makes us seem child-like and dependent. Change the name of the state “department of mental retardation.” Avoid the word, whenever you can. Refer to us as people with retardation, if you must. See us as people first.

And so went the truths stated in the declaration of independence forged at the first-ever convention of the self-advocates of People First of Connecticut.

Among people with mental retardation, self-advocacy refers to any banding together to secure rights. In California, self-advocates have picketed the state capitol to protest cuts in social service programs; others in Denver went on strike at a sheltered workshop where they were paid at piece rates, to demand the same pay as non-disabled employees there; members in Washington, D.C. started a voter registration and education project; and in Connecticut, Monroe helped self-advocates still living at a state institution call a well-attended press conference to demand their release from the institution and to be moved to group homes. Self-advocacy also is sometimes used to describe any act of self-determination, from picking a job to deciding not to have sex with a boyfriend or girlfriend.

There are thought to be at least 10,000 Americans with retardation who are active self-advocates around the country.

For certain, the movement is growing rapidly. There were 374 chapters of People First and other similar self-advocacy groups in 1990, according to an informal nationwide survey by the Association for Retarded Citizens of the United States. That compared to 200 in 1987 and 55 in 1985. Self-advocates have modeled themselves after the broader disability rights movement, the expanding battle for civil rights by people of various, usually physical, disabilities.

Underpinning the self-advocacy movement is a faith that people with retardation–even the most severely retarded person–can be taught to make good choices. “This is a free country. You can talk for yourself,” is the way Monroe explains it at the convention. “You might need some help, but you can talk for yourself.”

People with retardation cross a range of capabilities and experiences. This is reflected by the Connecticut self-advocates. Most live in group homes or with their parents, although a few live by themselves. Some, however, will go home from this convention to a cottage at an institution that has been home for most of their lives. Most have mild retardation, which is not surprising given that 90 percent of the six million Americans with mental retardation are classified this way.

Retardation means that a person has much greater difficulty learning than others. Some of the Connecticut self-advocates can read and write, while others have trouble making themselves understood. Most have jobs, although many are segregated in enclaves with only other disabled people.

The self-advocates run a model convention, starting with registration and coffee in the morning and concluding with a dinner-dance that ends at midnight. There is a seriousness to their work. The men come in coats and ties, the women in skirts and dresses. Monroe has worked for several months planning the conference, along with several self-advocates and advisors. He carefully decided every detail, from not having a head table–to avoid putting “all the big people up front”–to the issues for the resolutions.

Political leadership fits Monroe neatly, as if it were his birthright. The bearish Monroe, nattily dressed in a dark grey pinstripe suit, white button-down shirt and a red tie, is expansive and open. He is a populist hero and role model to the self-advocates, who know the outlines of his story. From the age of eight, he spent 11 years at the Southbury Training School, a state institution where he says he was raped and abused, and then another dozen years living in a large group home.

Now, at 38, Monroe has acquired the symbols of success: His own apartment in Hartford; a Japanese-model compact car with a sunroof; and a full-time job. Since 1984, he has worked as a veterinarian’s assistant, cleaning cat cages and giving flea baths to dogs. Monroe is a familiar figure, too, around the marble halls of the state capitol building, where he buttonholes legislators to urge them to spend more money on community group homes or to change guardianship laws. Several weeks before the convention, Monroe had been one of 3,000 activists invited to the White House to witness the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act, which expanded guarantees against discrimination to people with disabilities. As President Bush strode across the gently rolling South Lawn, Monroe had boldly presented him a handprinted letter with his thoughts on self-advocacy. “We are as good as any other person,” it said.

Monroe says self-advocacy is the most significant development yet for people labeled retarded. Many experts in the field of developmental disabilities agree. “This is of great importance and very positive for the future,” argues Brandeis University Professor Gunnar Dybwad, who is writing about the movement. Self-advocacy, he says, is a natural progression. Over the past decade there has been a consensus among professionals to create programs that take into consideration the individual needs of people with retardation. “It’s obvious,” says Dybwad, “if you start with the individual, then individuals need to learn to speak for themselves.”

Monroe says self-advocacy is the most significant development yet for people labeled retarded. Many experts in the field of developmental disabilities agree. “This is of great importance and very positive for the future,” argues Brandeis University Professor Gunnar Dybwad, who is writing about the movement. Self-advocacy, he says, is a natural progression. Over the past decade there has been a consensus among professionals to create programs that take into consideration the individual needs of people with retardation. “It’s obvious,” says Dybwad, “if you start with the individual, then individuals need to learn to speak for themselves.”

Self-advocacy is a second wave of revolt against the professionals who have run programs for people with retardation. The first came over the past three decades in the parents movement. But that movement, says Dybwad, one of its primary advocates, is “getting tired.” Jean Bowen, an advisor to Connecticut People First, believes self-advocates will be more forceful fighters for their rights than their parents ever were. “Parents have been told to have such little expectations for their sons and daughters to contribute anything, that they have been willing to settle for less,” she says. In the future, impetus for new programs will come largely from people with retardation, says Dybwad.

But if self-advocacy is a revolt against professionals and the non-retarded world, it also, paradoxically, remains dependent on people who are not retarded. Almost always, a self-advocacy chapter relies on a facilitator. This is a non-retarded advisor who helps break down complicated information but who, ideally, leaves decision making to the advocates. It is a fine line. Usually, a chapter’s character is determined by the advisor. Some chapters are primarily places to socialize. Others press an agenda dominated by political activism. That is the case with Connecticut People First whose chief advisor, Bowen, as director of the Western Connecticut Association for the Handicapped and Retarded, is active nationally on issues of the rights of people with mental retardation.

And if in Connecticut self-advocacy is a revolution, it is one that is encouraged, at least at arms’ length, by the very regime that is being challenged. Speaking at the Connecticut People First convention is Toni Richardson, the state commissioner of the department of mental retardation. “You are going to create a new world where everyone is included,” she says, comparing the self-advocates to Martin Luther King Jr. “All of you are responsible for a new era and I take my hat off to you.”

In the end, Richardson knows that self-advocacy will create more headaches for her. The people her department serves are being encouraged to complain about the way they are treated. But there are potential advantages, too. Richardson’s department faces budget cuts in fiscally-troubled Connecticut. The self advocates could become effective political allies to help push for more money for, among other things, the new group homes she would like to open. But the biggest selling point for self-advocacy, says Richardson, is that it is the right thing to do.

Richardson has known Monroe since 1969 when, fresh out of college, she took a job at Southbury Training School, where he was then living. Working in one of Southbury’s cottages as a residential aide, what she calls a “bottom of the heap” job, Richardson helped people eat, get to the bathroom, or get ready for bed. “A lot of the people who are part of self-advocacy now, I knew personally at Southbury 20 years ago. I remember what they were like, and what we, the staff, thought about their abilities. Now I see them in a whole different way, as colleagues and friends,” says Richardson. “I’m not sure if they grew, or we just grew in the way we looked at them.”

Ultimately, self-advocacy comes down to the issue that has always been at the heart of how we deal with people with retardation: How much protection do they need? For most of this country’s history, protection was something good, compassionate and progressive. Institutions for people with retardation had been built first in the 19th century by reformers seeking to help a vulnerable population. But today, these institutions are being depopulated and even shut down, as professionals come to agree that it is wrong to isolate people from the community around them. Today, such protection is seen as a paternalistic response that mires people in dependency, prevents them from learning how to take care of themselves and, in the long run, costs society more by forcing government to continually look after a dependent group.

At the same time, people with mental retardation, by definition, function at a significantly lower intellectual level than others. And that affects how they learn and how they make decisions. The Connecticut self-advocates are adults, but by virtue of their retardation they are also sometimes vulnerable adults. This distinction is clear at two afternoon workshops at their convention.

A standing-room-only crowd of 70 fills the workshop titled “Doing the Right Thing: How to Flirt.” A woman advisor to the People First chapter in New Haven shows videos of a party and then leads the group in some spirited role playing. You like someone you meet at a party. How do you let them know you are interested? Among the tips: Compliment that person on the clothes they are wearing; learn their name and use it frequently in conversation.

Ten steps directly across the carpeted hallway is “Saying No: We Don’t Want to Be Touched,” a solemn session run by the director of a local rape crisis center. Again, there are videos and role playing. Participants get on an imaginary bus and are approached by a molester, who sits next to them. Among the tips for spotting a potential molester: He compliments his victim on the clothes they are wearing; he asks their name and uses it repeatedly to win their trust.

Of the two seminars, the one on flirting succeeds precisely because it starts from an assumption that the people in the room are adults and, like others their age, are interested in flirting, dating and sex. The anti-rape session misfires because the moderator assumes, correctly, that the participants are vulnerable, but then incorrectly that their vulnerability and retardation makes them less than adults. People with retardation who live in group settings are thought to be more likely the victims of rape. Because of their retardation, people will try to take advantage of them. When the woman from the rape crisis center begins the workshop by asking for a definition of physical assault, hands shoot up. One woman says she was raped at an institution, but no staffer believed her. Another tells of being raped by a neighbor who knocked on the door of her group home when she was alone.

The 30 adults have come to the anti-rape seminar because they desperately want to exorcise their own bad experiences and to learn how to protect themselves. Instead, the moderator keeps everything safely in the third-person of role playing. She shows a video of elementary school children being approached by caricature-evil child abusers with arched eyebrows and smarmy smiles. She leads the group in unison in shouting out how to spot danger (“You get that uh-oh feeling!”) and then repeat what to do (“Say No! Get Away! Tell a Responsible Adult!”).

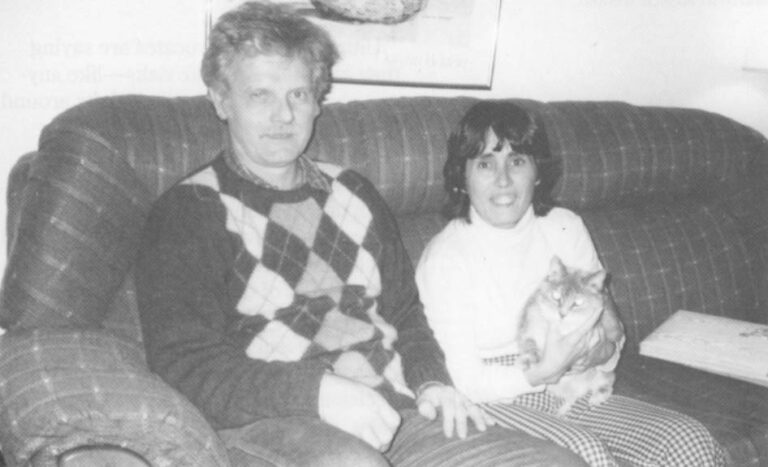

Ultimately, self-advocates arc saying they are willing to take risks–like anyone else–to live like other adults around them. They want places to turn to for support, but they want the feeling of respect and self-confidence that comes from taking chances. One of the most interesting self-advocates, at the Connecticut convention is Nancy Cleaveland, who is president of the People First chapter at the Southbury institution. She has lived at Southbury since she was nine. There, other people have always made basic decisions for her: What to eat, when to eat it, when to get up, when to shower, where to live, where to work, when to sleep. Now, at 52, Cleaveland wants an apartment on “the outside” with her longtime boyfriend, Richard Carlson, another resident of the institution.

The decision to leave is not Cleaveland’s. It belongs to a beloved 82-year-old aunt, her only family, who is her legal conservator. Cleaveland, with Jean Bowen’s help, has asked a legal service attorney to sue her aunt, Marion Mattoon, for control over such decision making. To Cleaveland, it is an issue of her “right” to live with Carlson. “Nancy is being incarcerated,” argues Bowen. “She is being held against her will, kept from her preferred place to live.” Mattoon calls it foolishness to think that Cleaveland and Carlson can make it on their own.

Her niece, she says, has been “brainwashed” by advocates and lawyers. “Everybody wants to paint the picture so rosy. But it’s not rosy,” says Mattoon, a retired special education teacher who taught people with retardation. She knows that a few previous attempts to move Cleaveland into a group home ended disastrously.

It is Cleaveland who steers a commonsense middle ground. She understands that living with Carlson, who is less capable than she, is fraught with risk. Besides, she has been hurt before when Carlson, who has a child by another woman, has flirted with other women. It is Cleaveland who ultimately decides that she wants to start out by living in a group home with Carlson and other men and women, or to have Carlson in a separate residence nearby. That way they can have their “privacy”, but also time to work out being together. In December, Southbury Probate Court Judge Mary Kay Flaherty agrees, making Cleaveland her own limited guardian. Cleaveland turns down a chance to live with Carlson in an apartment in Danbury, because it is far away from her aunt and Carlson’s mother. It will take at least several months to find a place that fits what Cleaveland and Carlson want.

To Monroe, self-advocacy means taking such risks. It means, as he told Bush in his letter, “being more independent, standing on your own two feet and sticking up for your rights.” Monroe’s own transition has been an often rocky one, sending him from heights of self-confidence to suicidal feelings of failure. There are bills past due, an unkempt apartment, a gnawing loneliness over scarce friends and lost family. “Do you ever get hurt?” he asks, and then, as if addressing Cleaveland’s aunt, continues. “Are you going to put a blanket over her again and suffocate her? You don’t need to do it.” It is like, he says “when a child gets on a bicycle the first time and falls off and gets a little bruise. Are you going to keep that child off the bicycle? No, you get right back on. That’s how people learn.”

©I991 Joseph P. Shapiro

Joseph P. Shapiro, an associate editor of U.S. News & World Report, is examining the disability rights movement.