The story of the disability rights movement could be written about Marilyn Hamilton’s impatience. It would start the summer day in 1978 when Hamilton crashed her hang glider nose down into the side of a California Sierra mountain. Her spinal cord was bruised and Hamilton became a paraplegic–a very impatient paraplegic.

Hamilton zipped through rehabilitative therapy in three weeks. Most people take at least three months. Then she was impatient with the bulky wheelchair–”a stainless steel dinosaur,” she called it–that her physical therapist ordered for her. It was too heavy to get back out on the tennis court. So Hamilton sought out her friends and fellow glider pilots Don Helman and Jim Okamoto. Helman was driving a truck delivering parcels for UPS. Okamoto was managing a motorcycle shop. But the two, best friends since kindergarten, were also brilliant weekend inventors. They had begun designing hang gliders from a shed on the farm near Fresno owned by Helman’s parents. Build me an ultralight wheelchair, Hamilton asked them, out of the aluminum tubing you put in your gliders.

What Helman and Okamoto designed was light and sturdy, weighing 26 pounds compared to the standard 50 pound wheelchair. It had a stunning geometry. Instead of being big and boxy, like other wheelchairs, Hamilton’s sky-blue wheelchair was sleek and sporty, with a low-slung back and compact frame that looked more like it belonged to a high-speed racing bicycle. So Hamilton, Helman and Okamoto went into the wheelchair manufacturing business, pushing the hang gliders to one side of the tool shed. They started selling their Quickie wheelchairs as fast as they could turn them out.

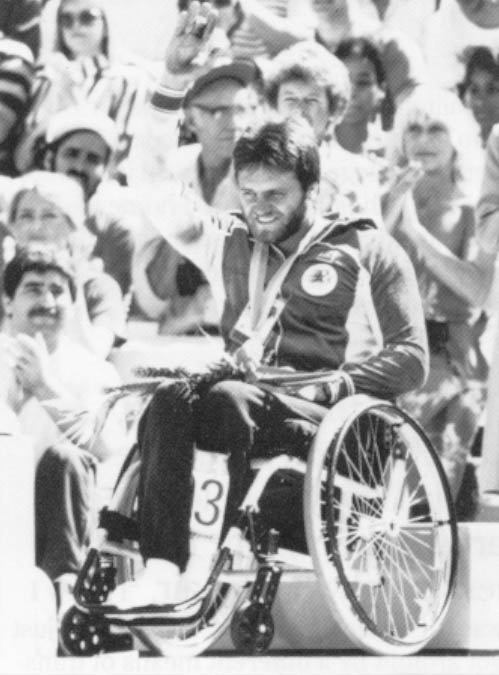

Hamilton would compete in wheelchair sports tournaments. With her cutting-edge chair, she became a two-time national tennis champion, beating out men and women, and a member of the U.S. disabled ski team. Other wheelchair athletes–a community known for cleverly modifying chairs in search of a competitive edge–would want a copy of Hamilton’s featherweight wheelchair. Sales skyrocketed once a folding version of the Quickie was introduced in 1983. Then people wanted the chair not just for sports, but for everyday use. Its lightness was liberating. It was light enough for a rider to wheel up to the driver’s seat of a car, jump in, and then, unaided, fold the chair, pick it up with ease and store it in the back seat. Within 10 years, Quickie would grow into a $40 million-a-year business and relocate to a 150,000-square foot facility. Purchased by Sunrise Medical, a large medical equipment company, in 1986, Quickie’s lightweight chairs would be imitated by all other wheelchair companies.

Most important, Hamilton had reinvented the wheelchair. She took a piece of medical equipment and made it fun and sporty. She took the universal symbol of sickness and turned it into a symbol of disability self-pride.

Uncle Bill was waiting for her, with tears in his eyes, at the back of the intensive care ward the day after the accident. Marilyn and this uncle by marriage always had been kindred spirits, two gregarious and instantly likable people who loved life, family and friends. Yet not until now would Marilyn start to understand how truly remarkable this uncle’s life had been.

Bill Hamilton was a quadriplegic. When he was a high school student, Bill was thrown from a Model T Ford. His neck snapped on the hard road. Quadriplegics almost never lived in those days between the World Wars. Rehabilitative medicine was just developing in a crude form in response to the return of paralyzed war veterans.

Now Bill, a large and dignified man, was at his niece’s side to pass on his more than fifty years of wisdom as a quadriplegic. “You can do anything,” he told her. “You’re bright. You’re adventurous. Don’t let that spirit die.” The high school where Marilyn taught home economics was reluctant to have her back. Bill welcomed her into the family fruit brokerage. The trade newspapers wrote about the “crippled” uncle and niece selling fruit out in California. She would work with Bill during the fruit season and spend several months each year traveling to sports events. At the same time, she began her wheelchair business.

Most of all, Bill made Marilyn understand that the wheelchair represented her liberation. When Bill was injured, the wood and wicker wheelchairs were rigid and rectangular with high backs. They were too wide to get through most doors, a reflection of the fact that most disabled people then were considered useless members of society. Wheelchairs were made for people who were closeted at home or who lived in institutions. Weighing 90 pounds, Bill’s first wheelchair was too heavy to move far by himself. Wheelchairs then were still largely for those rich enough to afford to hire someone to push the cumbersome contrivances. The Hamiltons hired two attendants for Bill, who assisted him 24-hours a day. He went to college and law school in Los Angeles. Then he returned home to oversee the expansion of the family orchard, successfully organizing other San Joaquin grape and tree fruit farmers.

From the beginning, Hamilton hated the “weird” way people acted around her in her first stainless steel wheelchair. “I knew I was the same as always,” she says. “I just got around by a different means of transportation.” But the gleaming wheelchair scared people, putting up a chromium wall of discomfort between her and the world. Even her doctor addressed himself to her husband, as if she were helpless or not even present. Friends saw her sitting in a wheelchair and their faces would cloud up, putting Hamilton in the odd position of always being perky and bright, the one to cheer them up.

So Hamilton designed wheelchairs to put people–users and those around them–at ease. Instead of chrome, Hamilton’s chairs came in a rainbow of hot colors. The customer could personalize a chair in candy apple red, canary yellow or electric green. Neon pink was added at a user’s request. “Screaming neon chairs,” Hamilton called them. A Quickie chair was fun, refuting the idea that the user was an invalid. (Quickie’s biggest competitor today is Ohio-based Invacare, a name that is an abbreviation for “invalid care.”) Quickie chairs said its riders were neither sick nor to be felt-sorry-for, nor were they less than anyone else. The only difference was the way they got around. “If you can’t stand up,” Hamilton likes to say, “stand out.”

Hamilton’s proud chairs struck a chord with the emerging disability rights movement. For one thing, there were more wheelchair users, up from half a million in 1960 to 1.2 million by 1980, most of whom were no longer living in nursing homes or institutions. By the 1980s, survivors of automobile accidents and other spinal cord injuries were cheating death in increasing numbers. People with degenerative neuromuscular diseases, such as muscular dystrophy, were living longer. Thousands of paralyzed veterans came back from Vietnam. They all had enjoyed full citizenship before their accidents and illnesses and, like Hamilton, rejected as old-fashioned the idea that they should be hidden away. A new class of wheelchair users was newly politicized and wanting a life of maximum independence. They were demanding curb cuts, lifts on buses and handicapped parking spaces. They had come to expect that they would go to college, take jobs, get married and sometimes even start families.

Hamilton’s brightly colored chairs tapped into this growing sense that there was no shame in being disabled. The only tragedy about being disabled, went the philosophy of the new disability rights movement, came in the barriers thrown up by society, whether it was an employer’s refusal to hire a paraplegic or a building made inaccessible to a wheelchair. Hamilton’s wheelchairs reassuringly said it was okay, it could even be cool, to be in a wheelchair. Even the double entendre of the wheelchair’s name, Quickie (“You need a Quickie,” goes one company advertising slogan) was a light-hearted mocking of the pitying “walkies,” the rest of the world, who seemed to automatically assume that the loss of the use of one’s legs must also mean the end of a sex life. Or that paralysis meant the end of a life worth living.

Some wheelchair history: A man who became a paraplegic in a 1918 mining accident sought out a friend in California, an engineer, and asked him to design a lightweight wheelchair. In 1932, the engineer built one that could be folded and put in the back of a car. It was such an improvement over existing chairs that the two men started a wheelchair manufacturing firm. Together, Herbert Everest, the paraplegic, and Harry Jennings Sr., his mechanical engineer friend, revolutionized wheelchair design, cutting the weight of a wheelchair from 90 pounds to 50 pounds. Their company, Everest & Jennings, would dominate the wheelchair market for the next 50 years.

It is 1991 and Barre Rorabaugh, the new president and chief executive officer of Everest & Jennings, is sitting in his spacious office in Camarillo, California late on a Friday evening. His wall to wall windows look out over the Ventura Freeway, an aquarium of colorful cars whizzing past, headed off for the weekend. E&J has hit on hard times and Rorabaugh, a corporate turn-around specialist, is talking about how he plans to return the company from the brink of bankruptcy. E&J lost over $88 million in 1989 and 1990 and laid off one third of its local employees. Rorabaugh is retelling the story of the paraplegic who asked an inventor friend to design a lighter chair and how their creation revolutionized the wheelchair and led to the establishment of the hottest wheelchair company in America. Rorabaugh speaks in respectful tones. He could be relating E&J’s proud story. But he is talking about Marilyn Hamilton. He is talking about how he will turn around E&J by learning from Hamilton’s success: He will listen to consumers; he will seek to dominate the lucrative lightweight market with a new generation of wheelchair made of even lighter plastic composites.

E&J lost its edge because the company got smug and stopped paying attention to what people in wheelchairs wanted, says Cliff Crase, editor of Sports ‘N Spokes, a magazine for wheelchair athletes. In the late 1970s, the justice Department brought an anti-trust suit, later settled, charging E&J with monopoly practices that set prices of wheelchairs artificially high and squelched competition and innovation from other companies. “People would suggest a change, something like a lightweight chair, and E&J would say, ‘Fine, make it yourself,’” says Crase. Even when Quickie came out with its ground-breaking chair, it took E&J several years to even enter the lightweight market. By that time, Quickie and other companies were battling for this fastest growing share of the wheelchair market.

By the 1980s, the company that had made wheelchairs for FDR and Churchill, shahs and sheiks, no longer had strong disabled officers at the top to advise them. E&J missed the rise of a newly independent generation of wheelchair users who, with new jobs and less welfare, were emerging as a powerful consumer group. In some ways, it was easy to overlook this consumer uprising. Unlike virtually every other product, wheelchairs are not sold directly to users. Instead, they are marketed through occupational and physical therapists and medical supply dealers who recommend them to disabled clients and customers. But Quickie understood that, to make its mark, it had to reach beyond these usually non-disabled professionals and speak to the growingly self-sufficient wheelchair users. Their product brochures showed their chairs being used by active people, who were pictured at the office, on the basketball court, on the dance floor, or in wedding chapels. The E&J sales material, until recently, kept to the tradition of showing their chairs pictured in hospital rooms.

Hamilton is relaxing at her stone and wood-beam weekend condominium on top of a mountain ski resort. She has flown in from an Atlanta meeting to unwind for the weekend, before taking off on another cross-country business trip. Hamilton is a familiar figure on the slopes, where she uses a special skiing device invented for paraplegics. There is constant pain from her injury. But she stays in top physical condition and, until a recent automobile accident, could wheel herself with ease from the base of the mountain to her condominium in the thin air at the top. She lives a good life now, validated by the little “presents” she has bought for herself: The ultra-powered red sports car; this vacation spot big enough for 14 family members to spend Christmas; and a new house of glass and steel so unconventional that she had to find a commercial builder to construct it.

On the way to the resort and back, the road winds past Tollhouse Mountain, the scene of her hang-gliding accident. As she drives past, she matter-of-factly notes its presence, but without looking directly at it. Its peak rises arrogantly in the distance. She speaks freely of the accident. For the first five years after the injury, Hamilton was convinced she would walk again. At first, she mastered a way to take “steps”. Putting all her weight on a short leg brace, she would plant one foot, then throw the opposite hip to send her leg swinging forward, repeating the painful process, literally a form of self-torture, for hours during morning physical therapy sessions.

It is not uncommon for paraplegics to believe they will walk again, despite all evidence to the contrary. It is a way to hide from the stigma of disability. There are daily reminders of the shame of not walking–from telethons seeking to cure “crippling” paralysis so that pitiable poster children can take steps again, to inaccessible homes, stores, offices and buses that say only those who walk can be included. But now, finally, the woman too impatient to ever take no for an answer accepts the fact that she will never walk again. It is only right that Marilyn Hamilton, who took the stigma out of using a wheelchair, should so be at peace.

©1991 Joseph P. Shapiro

Joseph P. Shapiro, an associate editor of U.S. News & World Report, is examining the disability rights movement.