Gary Zahm remembers it as just a feeling, a vague impression that something was wrong at the Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge, which he had just been put in charge of.

Mostly, it was the smell.

“I’ve worked in alkaline marshes all my career,” Zahm said. “And this was an alkaline marsh, but it didn’t smell right. It was like nothing I’d ever smelled before.”

There were other signs of trouble: The tips of the cattails were turning brown. Huge mats of algae were floating in the water. And, eeriest of all, the place was utterly quiet. The noises a person would normally expect to hear in a marsh–the croaking of frogs, the splashing of muskrats–were noticeably absent from Kesterson.

“It just wasn’t a healthy place,” Zahm said. “There were things missing that should have been there.”

That was in October 1980, and as things turned out, it was only the beginning. During the next four summers, prodded by Zahm’s observations and the curiosity of two of its biologists, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service uncovered a stunning wildlife disaster at this obscure refuge in California’s San Joaquin Valley. Ultimately, thousands of migratory birds were found dead, poisoned by a toxic chemical element called selenium. Its source: Subsurface drainage from irrigated farms, dumped at the refuge in ignorance by the Service’s sister agency, the Bureau of Reclamation.

In the eyes of irrigators and wildlife advocates alike, the Kesterson episode–and others like it–have brought irrigated agriculture to a crossroads. The nation’s taxpayers have already spent more than $11 billion to build the world’s most extensive irrigation systems. Now they may have to spend billions more to rescue those same systems from disastrous side effects like Kesterson.

Most of the San Joaquin Valley fits the climatologist’s definition of a desert–less than 10 inches of rain annually. Yet when the first Anglo settlers reached the valley in the mid-19th century, they found an immense marsh, fed by snow-melt from the Sierra Nevada. Vast flocks of waterfowl fed and nested in the marsh. Tule elk and pronghorn antelope grazed its fringes; grizzlies came down from the mountains to feast.

All that changed in 1942, when the Bureau of Reclamation put a concrete plug in the biggest Sierra river, the San Joaquin, and stopped the flood in its tracks. Today, the San Joaquin, its water diverted for irrigation, is mostly dry until it is joined by tributaries downstream. In a matter of a couple of years after its gates closed, Friant Dam dried up virtually every marsh in the valley.

Once the water was gone–too late, in other words–the Fish and Wildlife Service began to set up wildlife refuges in the valley. Finding land was not as big a problem as finding water; by that time, most of the water in the valley had been locked up by the Bureau or by private irrigators.

Meanwhile the Bureau had a problem of its own. In 1960, Congress authorized a new system of dams and canals called the San Luis Unit of the Central Valley Project. Unfortunately, the San Luis service area had one of the world’s worst drainage problems, thanks to a buried layer of clay called the Corcoran formation. For 30 years, growers had been pumping water out from beneath the Corcoran clay and dumping it all over their land to grow cotton. As much as half of that water trickled back down to the Corcoran clay and stayed there, creating a vast layer of brackish water that slowly crept upward. Now, with the growers’ wells running dry, the Bureau was going to put more than a million acre feet per year of new water on the same soggy ground.

The Bureau’s plan to deal with the drainage problem consisted, mainly, of more concrete. A 188-mile drainage canal, lined with concrete, would be built from the San Luis service area to the Delta. Farmers would be able to extract the shallow groundwater from their fields with networks of buried pipelines; then they would dump the drained-off water into the drain canal. There was only one complication: The people of Contra Costa County, which would be at the mouth of the San Luis drain, were incensed at the idea of millions of gallons of junk water being dumped in their backyard. They got Congress to put a rider on the project’s annual appropriations act that blocked the Bureau from finishing the drain.

At that point, a more prudent bunch of bureaucrats might have held off on delivering water to the San Luis service area, to avoid making the drainage problems there any worse. Instead, the Bureau decided in 1967 to go ahead and deliver the water and then wait, hoping the opposition in Contra Costa County would somehow go away. In the meantime it built the first part of the drain, an 82-mile section from Mendota to Los Banos, where there would be a set of holding ponds designed to even out flows in the drain from season to season.

By 1969, the Fish and Wildlife Service was desperate for any scrap of duck habitat it could lay its hands on, no matter what the strings attached. So on July 23, 1970, the Service and the Bureau signed an agreement to make the holding ponds into the Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge.

Years passed, and the Bureau watched in dismay as the Contra Costa County forces grew stronger, not weaker. Meanwhile, farmers in the Westlands Water District, the largest district in the San Luis service area, kept dumping scads of water on their land, and their water tables shot upward. In the late 1970s, in desperation, they started putting drain lines under their fields and dumped the excess groundwater into the half-finished San Luis Drain.

Thus in 1978, the Bureau had an 82-mile drain; 1,280 acres of ponds at Kesterson and a flood of salt-rich water coming down the drain from Westlands. The Bureau then did the only thing it could do–it dumped all of the rotten water into Kesterson and left it there. Slowly, the salt content of the ponds began to rise. Gary Zahm was assigned to the refuge two years later; by then, the flow into Kesterson consisted almost entirely of drain water.

“When I first got here, I noticed there weren’t any fish in the reservoir, other than mosquitofish,” he said. “There weren’t carp; there wasn’t anything, and there should have been. I just assumed–and I’m not sure it was a good assumption–that it was just from the salts. But a striped bass should have been able to live in there; it’s a goddamned ocean fish, you know?”

Zahm mentioned his concerns to his supervisors, but otherwise kept them to himself until 1982, when he talked to Michael Saiki, a Fish and Wildlife Service fisheries biologist. Saiki’s interest in Kesterson and the San Luis Drain had been piqued by a meeting he attended in February 1982 with people from the Bureau of Reclamation and the state Water Resources Control Board. At that time, the Bureau was getting ready for another try at getting the drain finished to the Delta, and it was testing the drain water to find out what chemicals were in it. One chemical was selenium; it was beginning to look like there was quite a lot of it in the drain water.

In April, Saiki and another Service biologist, Harry Ohlendorf, went to Kesterson to tour the refuge. A month later, Saiki netted some tiny mosquitofish from Kesterson and sent them off to be tested. He also submitted some fish from the nearby Volta Wildlife Area, a small refuge that usually received clean water that escaped from a Bureau canal. The results showed that selenium levels in the Kesterson fish were 70 to 100 times higher than they were in the Volta fish.

Saiki called Ohlendorf with the results, and Ohlendorf went to the library. After a couple of hours of research, selenium suddenly began to seem like a very big deal.

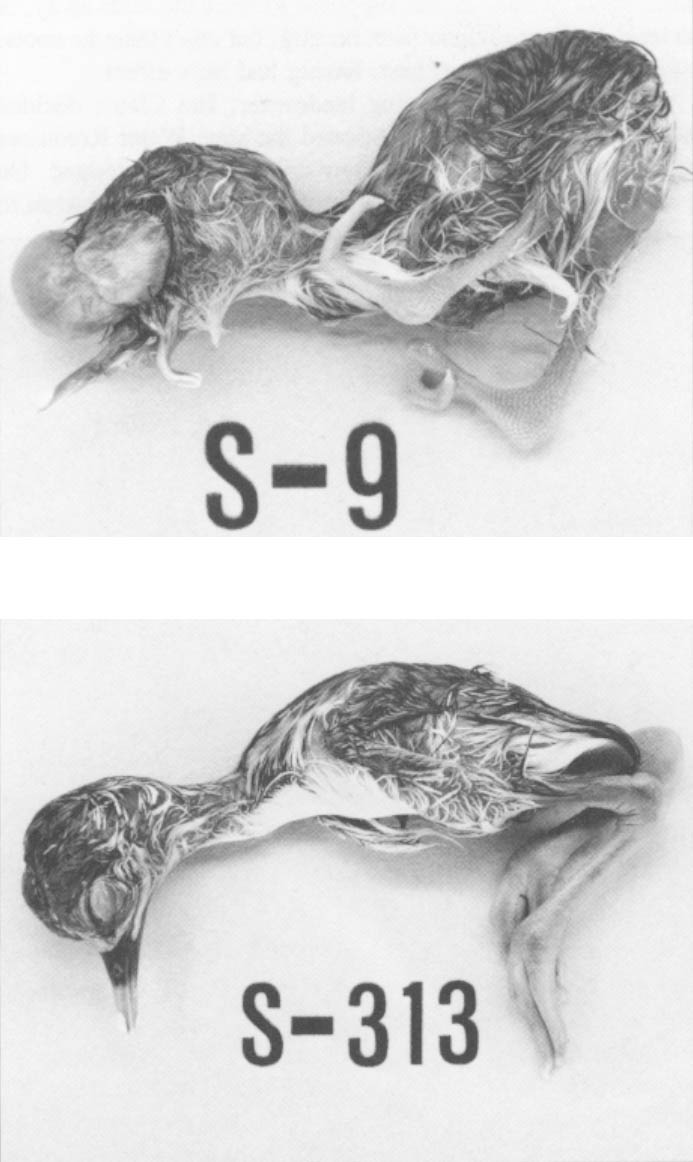

“The levels of selenium in the mosquitofish at Kesterson were roughly 10 times the levels that had caused reproductive effects in chickens in studies that were done back in the mid-30s in South Dakota,” Ohlendorf said.

“In the South Dakota studies, what happened was that at many of the farms, the farmers were unable to feed grain they grew on their farms to their chickens, and have the eggs hatch. The eggs wouldn’t hatch. They’d have either dead embryos or severely deformed embryos.

“Basically, what they found was that the selenium levels were very high in the grain, and this was causing monstrosities, as they called them then, in the eggs and the embryos.”

By that time, Saiki and Ohlendorf had already proposed a major study on Kesterson. They tried to get money from the Bureau. But in a meeting with the Bureau’s regional water quality branch chief, Don Swain, and one of his engineers, the scientists were told the Bureau wasn’t interested.

“Even if money was available,” Saiki wrote in a memo to “the record,” “[the Bureau] has decided not to fund our research at Kesterson Reservoir because the data would not immediately help [the Bureau] to obtain the [drain water discharge] permit for the bay-delta.”

Once the mosquitofish results came in, the Service brass decided to pay for Ohlendorf’s and Saiki’s proposed studies out of the agency’s own budget. In 1983, Ohlendorf spent most of April, May and July at Kesterson collecting eggs and hatchlings of ducks, shorebirds, coots and grebes. Saiki sampled water, sediment, plants and insects. The birds, Ohlendorf discovered, had selenium levels 10 to 20 times higher than the same species at Volta. They also had the same kinds of “monstrous” deformities that had been found in South Dakota.

“Here were these birds hatching out,” Ohlendorf said. “They had no eyes, no legs, no beaks…Some of them couldn’t hatch because the deformities were so severe. Then there were also these embryos that just died before hatching. Mostly it seemed to be related to selenium.”

Ohlendorf spent the next summer collecting more eggs from Kesterson, but he narrowed his focus to just two species, coots and stilts, both of which had been nesting plentifully at Kesterson the summer before. It wasn’t long before he noticed something else was wrong.

“We searched all the same places where we found coot nests in 1983, but we found 92 nests in 1983 and in 1984 we found nothing,” Ohlendorf said. “What we were seeing instead were dead birds.”

First, the fish had died; then the chicks hatched with deformities; and now adult birds were dying in the ponds. It wasn’t long before somebody in the Fish and Wildlife Service opined that the Bureau was violating the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which makes it a crime to “pursue, hunt, take, capture or kill any migratory bird, nest or eggs” except as authorized by law.

The Bureau’s remedy was to get rid of the birds. Crews were stationed at the refuge with shotguns and propane-fueled noisemakers; scarecrows were planted within the ponds. The “hazing” program, as it was called, was expensive–it cost $180,000 per year for more than three years–and it was an utter waste of time. It was supposed to scare the birds away, or at least discourage them from nesting, but other than the coots, which were too sick to nest, hazing had little effect.

Eventually, a neighboring landowner, Jim Claus, decided he’d had enough. Claus petitioned the state Water Resources Control Board to order the flow of drain water stopped. On Feb. 5, 1985, the board did just that, ordering the Bureau to stop the flow of drainage into Kesterson and purge it of selenium within three years.

By that time, Kesterson had become the biggest news in the valley. On March 15, George Miller, a Contra Costa congressman who had just become chairman of the House subcommittee on water and power resources–the Bureau’s overseer–called a field hearing on Kesterson at the Los Banos fairgrounds. It was there that the other shoe dropped.

Carol Hallett, a special assistant to Interior secretary Donald Hodel, was the first major witness. Eleven sentences into her testimony, she dropped a bombshell: “Policy-level officials in Washington have concluded that because the hazing program at Kesterson has not proven to be as effective as was hoped, and because of the prohibitions of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, immediate action must be taken…” she said. “Therefore, the secretary has instructed the Bureau of Reclamation and the Fish and Wildlife Service to begin the process of shutting down the Kesterson reservoir. This process will result in plugging the San Luis Drain and stopping the delivery of irrigation water to the lands which drain into the reservoir.’

Hallett’s bombshell couldn’t have come at a worse time for farmers on the 42,000 acres that drained into Kesterson.

“My name is Jim Gramis, ex-farmer, as of about an hour and a half ago,” a grower testified after Hallett was finished.

“We are in the middle of production, or in preparation for production, for planting. We have tomatoes that have emerged. We will never bring those crops to harvest. We are not only bankrupt; we are devastated.”

Not surprisingly, Westlands immediately threatened to take Hodel to court over the irrigation shutoff. During the next two weeks, officials of Westlands, the Bureau, the Service, the Interior Department’s solicitor’s office and the Justice Department worked out a compromise. Water would continue to flow to the 42,000 acres; Westlands would cut back the flow of drainage in five stages; and by June 30, 1986, the subsurface drain lines emptying into the San Luis drain would be plugged, stopping all flows to Kesterson.

The deal was a bittersweet one; in return for a definite shutoff date, Interior would have to accept that Kesterson could remain polluted by drain water through two more nesting seasons–1985 and 1986. Ultimately, the Fish and Wildlife Service found dead and deformed birds at Kesterson in each of those years, and in 1987 as well.

By the end of 1988, the last water had been drained out of Kesterson. No longer a marsh, it had become an arid grassland. In the spring of 1989, wildflowers sprouted by the thousands. Field mice moved into the old ponds; killdeer, eagles and hawks hunted there. The poisoning of waterfowl at Kesterson, which had been a fact of life for most of the past decade, was a thing of the past.

Harry Ohlendorf testified before the state board again on June 28, 1989. New data from Kesterson, he said, showed that killdeer and meadowlarks–dryland birds–had levels of selenium in their bodies that were 10 times normal, probably high enough to cause deaths or deformities.

There was no reason, really, to believe that Kesterson was unique.

Six months after the Kesterson shutdown, the Sacramento Bee published the results of its own tests showing high selenium levels at wildlife areas throughout the West–California’s Salton Sea; Arizona’s Imperial refuge; Bosque del Apache in New Mexico; Desert Lake and Stewart Lake in Utah; Bowdoin, Benton Lake and Freezeout Lake in Montana; Deer Flat in Idaho; and the Belle Fourche and Cheyenne rivers in South Dakota. The following spring, the Interior department added a few more–the Kendrick reclamation project in Wyoming; the Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge in Nevada; the Tulare Lake basin in California. More were added later: Malheur refuge in Oregon, Sweitzer Lake in Colorado, the Arkansas River in eastern Colorado and western Kansas. Other substances joined selenium on the list of drainage water chemicals that could be toxic to wildlife–arsenic, molybdenum, lithium, boron–a virtual periodic table of contaminants. They had been there all along, apparently. But until Kesterson, nobody bothered to look.

©1990 Russell Clemings

Russell Clemings, a science writer on leave from the Fresno Bee, is writing about salinity, selenium and the future of irrigation in the American West.