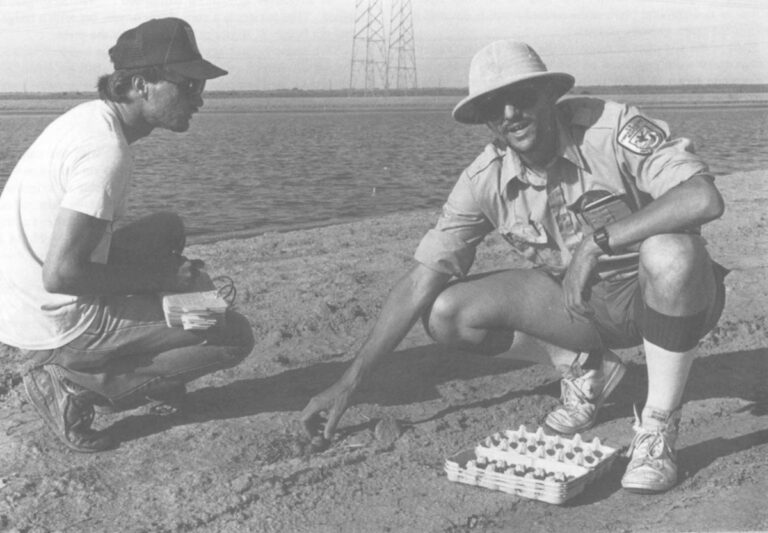

LOST HILLS, Calif.–On a recent May afternoon when the temperature was toying with triple digits, Dr. Joseph Skorupa, a federal wildlife biologist looking for bird eggs, walked a low earthen levee between two vast pools of shallow water.

With light-colored clothing and a broad-brimmed hat, Skorupa was dressed for the desert appropriately, because this place, where the mind-numbing heat can evaporate a year’s worth of rainfall in a couple of weeks, is exactly that, climatologically speaking: A desert.

But if this is a desert, then why was Skorupa surrounded by water, more than a solid square mile of water in all? Why, on the plains beyond the pools, were there manicured squares of green and gold crops, instead of the usual desert hues of brown or gray or rust? The answer lies in the one thing that makes the western United States the relative paradise it is today, instead of the moonscape it used to be–its far-flung system of plumbing. Hundreds of reservoirs; thousands of miles of canals and pipelines; countless pumps–all delicately choreographed to move water from where God in his wisdom put it to where man, in his wisdom, thinks God ought to have put it.

Now Joe Skorupa, the biologist who picks up eggs on these ponds and takes them apart in his lab, may be the man who brings down that technological house of cards.

The water that nourishes the farms around Lost Hills fell to earth not here, in the southern San Joaquin Valley, but 400 miles away, in the Feather River basin of the northern Sierra Nevada. It was shipped here in a network of canals that took 40 years and $6 billion dollars to build and may swallow $12 billion more if it is ever completed. Through these canals and their pumps, water defies gravity; it literally runs uphill toward money and political power, it is sometimes said. Through these canals, western farmers have brought 40 million acres of new land under the plow since 1939, thereby helping to drive 118 million acres of other farmlands into retirement. Through these canals, California has become the most productive farm state in the nation, leading Texas and Iowa, its nearest rivals, by a margin of almost $5 billion a year.

Skorupa is here to study what happens to the multitudes of birds that swarm at the other end of this plumbing system, around the vast pools of water known as evaporation ponds, shallow basins where the Feather River water is dumped when it’s too full of salts and minerals to be of any use for farming, when the only thing left to do with it is to give it back to the sky. Growers say that if they couldn’t use evaporation ponds, their crops would be slowly poisoned by a buildup of plant-killing salts in the soil. But now, Skorupa is proving that whatever their value to crops, the ponds are also death traps for migrating birds–luring them with the promise of calm water, plentiful food and safe nesting sites, then maiming their progeny with a strong dose of naturally occurring chemicals that are concentrated to lethal levels by irrigation.

Unless you’re hunting in accordance with the game laws, killing migratory birds is illegal. So now, the districts and farmers that operate these ponds–including some of the biggest growers in the world–are being threatened with prosecution under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. In public forums around the state, their hired experts have vilified Skorupa, attacking his competence, questioning his conclusions, accusing him of conducting bad science. Even the brass in his own agency, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, has ganged up on him. In Skorupa’s most recent report, which contained his latest data on birds in the evaporation ponds, a deputy director of the service’s research branch excised Skorupa’s conclusion, which advocated stricter contaminant standards on the ponds.

“The final paragraph was basically the ‘so what?’ paragraph,” Skorupa said. “It was the whole point to the document…”

“I began with the Fish and Wildlife Service because I wanted to work for the Fish and Wildlife Service. But what I’m working for is the Timber, Minerals and Agribusiness Service. At least that’s the way it’s been operating.”

On this May afternoon, like most other weekday afternoons the past three summers, Skorupa was collecting eggs. This particular day, he was looking for the mottled brown eggs of two spindly species of shorebirds–American avocets and black-necked stilts–that teeter through the shallow water on clownishly long legs, pecking at brine shrimp and fly larvae. Hundreds of these birds, maybe thousands, flew away as Skorupa approached their nests.

How these two species of birds happened to be nesting on the evaporation ponds is a lesson in how things can go wrong. In 1983, another group of federal wildlife biologists was studying the effects of irrigation wastewater at the Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge near Los Banos, about a hundred miles north of Lost Hills. The federal Bureau of Reclamation, which built most of the vast California irrigation system, had been dumping the wastewater to evaporate in 12 shallow marsh ponds covering 1,280 acres at Kesterson. Among the things the biologists found were an almost complete absence of fish and frogs, and monstrous deformities in the unhatched embryos of ducks and other waterfowl. The photos the scientists took were gut wrenching: Tiny ducklings, their downy feathers still matted with amniotic fluid, were posed against a pastel background in harsh lighting like so many thalidomide victims.

After a year and a half of debate, with the Fish and Wildlife Service squaring off against the Bureau of Reclamation and the irrigators, the government invoked the Migratory Bird Treaty Act against itself and shut off the flow of polluted water into Kesterson.

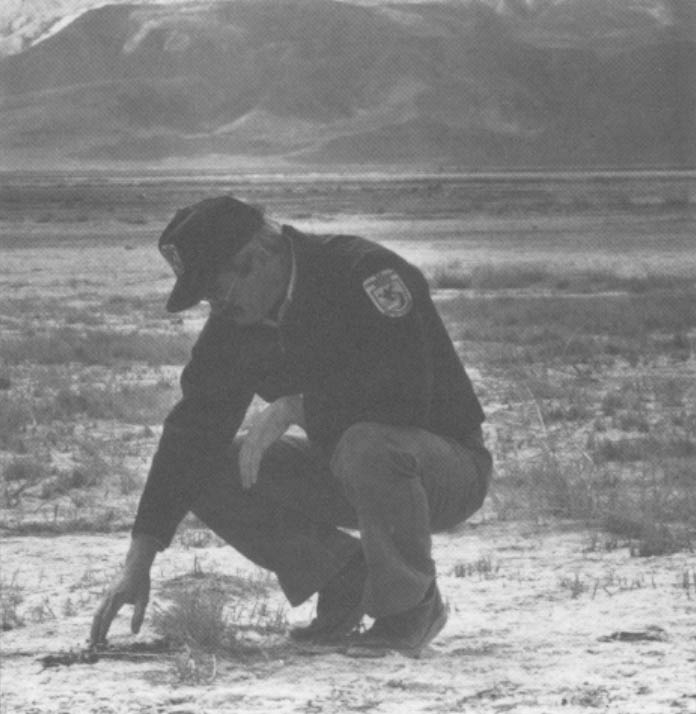

Though the irrigators insisted that Kesterson was a fluke, the Fish and Wildlife Service wasn’t convinced, so it widened its search for the effects of wastewater from irrigated farms. First, it looked next door to Kesterson, in a 52,000 acre system of privately owned duck marshes known as the Grassland Water District; there it found that the birds and their eggs were carrying a potentially lethal load of selenium, the chemical element that was blamed for the damage at Kesterson. Later, with the help of the U.S. Geological Survey, the service started looking at other irrigation projects around the western United States. So far, it has found serious problems with selenium and other natural trace elements at wildlife areas in 11 of the 17 western states. One major hot spot was the Tulare Lake basin, location of the Lost Hills evaporation ponds. Another was across the Sierra, near Fallon, Nev., where the Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge was quietly choking on an irrigation-related soup of chemicals.

Ronald Anglin, manager of the Stillwater refuge, is in the unenviable position of watching the marshes he manages sicken and die. That he is not alone is scarcely a comfort.

“These species have got the same problems at Ouray refuge in Utah, at Great Salt Lake, and up in Montana,” Anglin said. “They’re coming down the flyways and they’re just getting socked.”

Although selenium and other trace elements pose a serious threat to wildlife and irrigation throughout the West, there is an even more insidious substance that may pose a greater peril to agriculture in arid lands–the very salt that the flow of wastewater is supposed to carry away from the farms.

All water, except that which falls directly from the sky, contains significant amounts of various salts–not just the familiar ones such as table salt (sodium chloride), but obscure chemical salts like sodium sulfate and calcium sulfate, or gypsum. Ordinarily, the natural cycles of evaporation and precipitation keep salt levels pretty much in balance in the soil. But when mankind alters the natural regime–most notably in large-scale irrigation projects–the salt balance can be drastically altered as well. River waters of low salinity are hoarded behind dams, where the sun drinks up pure water and leaves all of the salt behind in the remaining water. Later, when the stored water is used to irrigate a field, the same thing happens: Pure water evaporates from the soil, or is transpired from the pores of the crops. All of the salts stay behind. Very quickly, they can build up in the soil to levels that are harmful to plants.

“Even though there is salt dissolved in the water, the plant basically has to take up pure water,” said Glenn Hoffman, a salinity researcher and head of the agricultural engineering department at the University of Nebraska.

“So the saltier the water is, the more energy the plant has to expend to keep the salt out,” Hoffman said. “If it expends energy to keep the salt out, then there’s less energy left to grow. So what you end up with is a plant that’s just smaller, and grows slower.”

To avoid the loss in yields that results from a salt buildup, farmers in irrigated regions use extra water, beyond what the plant needs, to wash the salt away from the roots of the crop. What happens next to that extra water–called the leaching fraction–is problematic. In regions where the subsoil is porous or the water table deep, it may not cause any trouble at all. It may just seep into a nearby river bed, or accumulate far below the surface of the ground. But in many desert areas that’s not the case. The soils themselves are dense, and below the surface lie even denser layers of clay or concrete-like hardpan, which blocks the downward flow of water. Instead of draining away, the salt-laden water stops at the clay layer, forms an underground pool, and eventually builds up until it affects the crops growing above.

Such is the situation in much of the San Joaquin Valley. Dense clays were deposited on the valley floor in the late Pleistocene epoch, 600,000 years ago, when the valley was a vast, shallow lake of glacial meltwater. In later geologic times, erosion washed sand and silt down from the nearby Coast Ranges, making the land perfect for the plow. But beneath the marvelously friable soil still lay the layer of clay, known now as the Corcoran formation, at 400 to 600 feet beneath the surface. When irrigation began in earnest during this century, season upon season of salty leaching fractions began to build up atop the Corcoran clay. Today, an estimated 500,000 acres of the San Joaquin Valley have a saline water table within five feet of the surface–close enough to affect the growth of plants. In short, the valley is like a giant flowerpot without a hole, a bathtub without a drain.

An entire branch of engineering has grown up around the problem of salt in irrigated agriculture, and it goes by the rather mundane name of drainage. Within the U.S. Department of Agriculture there is a group of scientists at a Riverside, Calif., laboratory who are experimenting with salt-tolerant plants, techniques to reduce the leaching fraction, and novel methods to re-use saline drainage water. Yet none of these methods is in wide use. Instead, the most popular means of dealing with the drainage problem is two-step: First, install a system of perforated underground pipelines, emptying into an open ditch, to carry the saline water away from the field. Then, just get rid of the drainage water, by any means possible.

In the San Joaquin Valley, much of the drainage is flowing into the San Joaquin River, causing problems for farmers in the river’s delta downstream, near Stockton. Most of what’s left goes into more than 7,000 acres of evaporation ponds like the ones at Lost Hills. For a time in the early 1980s, some of the drainage also went to the Kesterson refuge. Now that the government has ordered that flow stopped, the salty drainage is once again building up beneath 47,000 acres of active farmland, its eventual fate still to be decided.

The problems posed by irrigation drainage, and what to do with it, are far from new. Archeologists since the late 1950s have attributed the decline of the great Mesopotamian civilizations of the Fertile Crescent, at least in part, to a miserable failure in dealing with the consequences of desert irrigation. What was once the breadbasket of ancient Sumeria is today a salt-caked wasteland in southern Iraq.

But though irrigation is not a new practice, it has never before seen the kind of growth it has had in the present century. As a result, the dramatic deaths of baby birds at Kesterson, and the specter of other Kestersons throughout the West, are now forcing modern irrigators to confront head-on a question they would just as soon ignore for a few years longer: How to keep the fragile prosperity of 20th century irrigation from withering away in the 21st.

Jan van Schilfgaarde, an associate director of the Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service, has spent much of the past four decades working on answers to that question. The prognosis, he says, is unclear.

“Is irrigation agriculture sustainable?” van Schilfgaarde asked. “The answer is a very clear-cut yes, but with a hedge, and the hedge is: If you’re willing to pay the price…

“We know enough about how to manage irrigated land so that we can keep it productive indefinitely. But we’re kidding ourselves if we say we can do that without some environmental insult. And whether we’re willing to pay that price is a political decision, not an engineering decision.”

The stakes are enormous. California, with the nation’s largest farm economy, is utterly dependent on irrigation–82 percent of its agricultural output is attributable to irrigation. The figures are even more extreme in other western states. Except for a narrow strip of land in the Pacific Northwest, the West today is what the historian Walter Prescott Webb, in a May 1957 Harper’s magazine article, called “an oasis civilization,” largely unfit for humans without irrigation.

It’s no wonder, then, that local and state politicians in the West are sensitive to the threat that the drainage problem poses to their irrigated farming economies. Yet on a national level, there is a lot of evidence that retiring some irrigated lands from production might not be such a bad idea.

Irrigation projects built by the Bureau of Reclamation, which serve 9.9 million acres of irrigated farmland, get several subsidies from the federal treasury–the most significant being that although farmers who use Bureau water have to pay back the cost of their project, they have 50 years to do it, without interest. Meanwhile, the Department of Agriculture provides another subsidy through its price support programs for major crops like barley, cotton and rice–three crops that are widely grown on irrigated farms in the West.

A 1984 study by the two agencies showed that 48.2 percent of the seven USDA “program” crops grown in California were grown on land irrigated by Bureau of Reclamation projects. California grows more than half a million acres of upland cotton–equal to a square plot of cotton measuring 28 miles on a side. Fifty-five percent of that cotton is grown on Bureau projects.

Joe Skorupa’s study of the Lost Hills evaporation ponds began in 1987. That year, he found 300 nests of shorebirds on 398 acres of ponds. Since then, the growers who operate the Lost Hills ponds have expanded them to their present 680 acres as more and more of their fields have required drainage. Last year, Skorupa found 600 nests. This year, he’s expecting even more.

“It’s not out of the question that we could have more than a thousand pairs of shorebirds nesting there this year,” he said. “In the three years that we’ve been working there, and after we reported that there was a problem, the system’s expanded and it’s exposing three times the number of birds to contaminants than it was when we reported there was a problem.”

Skorupa is critical of the failure of state and federal government agencies-including his own–to protect the birds from the contaminated ponds. But he said he thinks that is changing–that the Interior department is about to invoke the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, just as it did at Kesterson.

“The evaporation pond game is almost over,” Skorupa said, “and the growers had better start thinking of somewhere else to put this water.”

©1989 Russell Clemings

Russell Clemings, a science writer on leave from the Fresno Bee, is examining salt, selenium and the future of irrigated agriculture in the American West.