Text and Photos by Victoria Pope

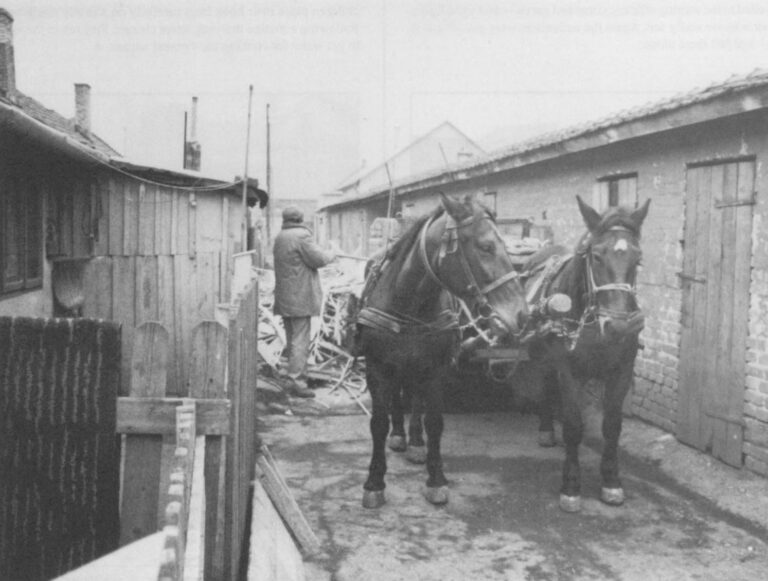

MISKOLC, Hungary–On streets without names, collapsed sheds circle the slag-heaps of the metal factory. Pigeons coo among the refuse. When dawn breaks, the wake-up sounds of coughing and coal-shoveling echo through the treeless hinterland. The gypsy community of Miskolc is waking up.

Eva Gulyas is already dressed and combing her daughter’s hair when the two men arrive at her door. It is 7 am, but she offers the visitors shots of Barack, an Hungarian peach brandy. The men toss down the drink and Gulyas starts putting boots on her three year-old daughter. The boots are the right size for a child twice as big as the black-haired girl dangling her feet from a settee covered with torn cotton batting. A snow jacket goes on next. Its sleeves stop at the child’s elbows, and it is too small to zip up. “They say I need to pay a fine,” says Gulyas, pulling a dog-eared paper from the pocket of her parka. The men huddle over her and read it, taking notes.

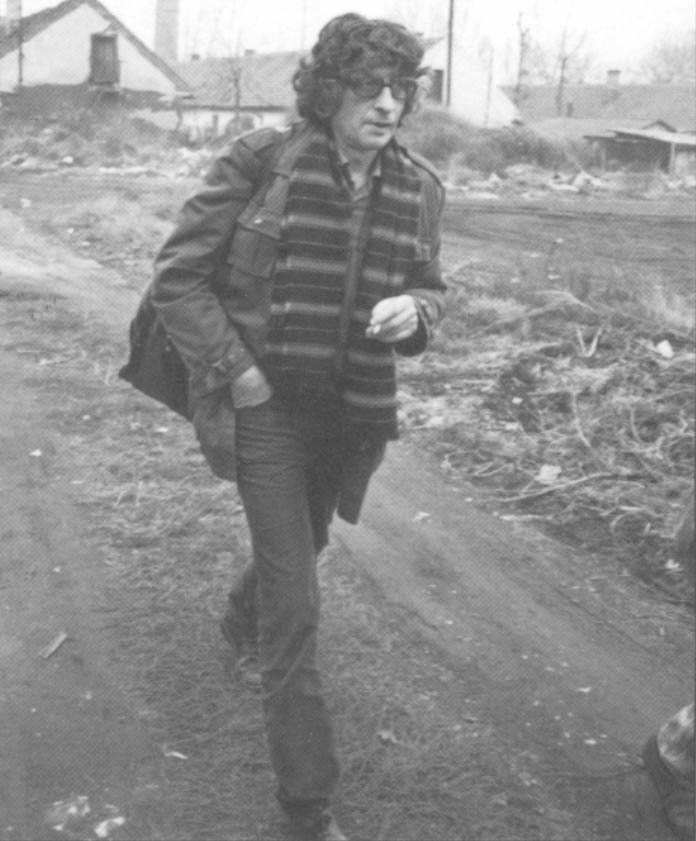

The visitors begin their questions in quiet, monotone voices. The older of the two is Gabor Havas, a well-known sociologist and dissident. Havas has spent countless hours in homes like this one, working with Hungary’s poor over several decades.

Whether by design or natural inclination, his approach is gentle, almost shy. He speaks very little and listens hard. Dark curls flap over his black-rim glasses as he nods in assent.

Standing next to Havas is Aladar Horvath, a young gypsy activist. Horvath, in charge of a community center down the road, has come to know these shanty-town dwellers by name. Some of them come to the roundtable discussions he leads. Horvath gets right to the point in these evening sessions. “Why are gypsies so hated?” he asks. The answers reflect bewilderment. “We have dark skin;” “We are different;” or “We were born under an unlucky star;” are common replies.

Changing times brought Horvath and Havas together. When new freedoms came to Hungary, even the downtrodden began thinking about ways to improve their lot. The end of the communist monopoly on power ushered in the creation of new independent groups. To the surprise of many Hungarians, the gypsies were quick on the mark, announcing the creation of their own political grouping. Called Phralipe–meaning Brotherhood, it was the first gypsy group in Hungary to speak out for gypsy rights. In a similar move, a party for gypsies was also founded recently in the Slovakian region of Czechoslovakia. In the past, the only voices for gypsy communities were the “official” organizations which marched lock-step with the regime.

The new political pluralism also gave a leg up to organizations that wanted to help gypsies. Social workers like Havas had worked for years at the barricades, fighting a poverty that was not officially acknowledged. With a newly unfettered press, and more accurate compilation of data, social scientists may now work more like professionals.

One of the biggest tests for gypsy advocates came right in the city of Miskolc. The trouble began when local communist bosses hatched a plan to revitalize the downtown. Miskolc is a gritty city, full of smokestack industries and ugly high-rise neighborhoods. But in the heart of the old town there remains fine old Baroque architecture and Hapsburg-style coffee houses. Local politicians saw their chance. Just 3 hours from Budapest, Miskolc could realize a tourism boom, with the proper restoration effort. There was one thing standing in the way of success: The downtown was full of gypsies who lived or congregated in the downtown.

So they went about solving the problem as they had solved it many times before. Bureaucrats shot off official slips demanding the gypsy families leave the area. Then they hatched a further plan. They would build gypsy housing outside the city limits far from any tourist’s itinerary.

But if the good old boys of Miskolc were just doing what came naturally, their adversaries had other ideas. Emboldened by the new political climate of openness, gypsy activists fought back. Declaring the city’s proposal an attempt to create a “gypsy pogrom,” leaders of the gypsy community protested the decision through the Raoul Wallenberg society, a human-rights association based in Budapest. They had other objections besides the forced nature of the move. The housing site was smack in the middle of a swamp. It was many miles from the closest bus station. Shocked by the backlash against the move, city officials put the housing plan aside, although they never officially canceled it. But they still evicted as many gypsies as possible from the center of town.

Valeria Zsiga and her family were among those forced to relocate. They were moved from a downtown flat to an apartment building, not far from where the gypsy housing development was planned. It is a barren corner of the city. Its window frames are crumbling. Glass panes are shattered. Most apartments haven’t central heat. Most of the tenants leave the doors of their stoves open to warm the rooms. Everywhere there lingers the sickly smell of flesh: A slaughter house is on the ground floor. Many of the young children are afraid to use the hallway toilets at night: too many rats. Zsiga says she is ashamed to tell her friends where she lives because it is so broken down. Indeed, from a distance, the building looks abandoned.

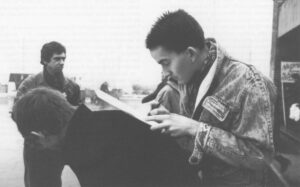

Havas, Horvath and a third colleague, sociologist Janos Ladanyi, visit the apartment building and take note of the squalor. Ladanyi is as boisterous as Havas is quiet. He careens down the hall of the ramshackle apartment building, exclaiming and muttering over the decay. The gypsy teenagers smoking cigarettes in the corridor smile, and laugh over Ladanyi’s intensity.

In the course of the visit, the social workers decide to take the case to a local lawyer. They choose Laszlo Matyi, who greets them warmly at his modest office near the city center. The office gives the impression of great industry: a long line of case folders cover the worn beige carpet in back of his desk. Matyi’s tie is loosened, and his shirt-bottoms hang out, though it isn’t even noon.

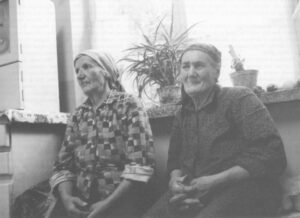

The lawyer will try and see what he can do for Mrs. Zsiga, who is fighting to relocate back in the city center. She breaks down and cries when she recalls the relative advantages of life in that neighborhood. “My grandchildren went to the kindergarten in the downtown when we lived there,” she explained. “Now they can’t go–we live too far from public transportation.”

At one time Mrs. Zsiga’s complaints would have been ignored by all but stalwarts like Havas and Ladanyi. But now she has other tools for combating discrimination. She was invited on to a local radio program which got wind of the controversy. Today, in preparation for another press interview, she has changed into a ladylike black nylon dress with yellow-rosebud print. Her hair is curled and her expression serene. A television reporter from Budapest enters the room with cameras rolling. Press censorship has been almost completely lifted, and journalists are only too happy to write about the social problems that were taboo for so long.

Some of Hungary’s political parties have expressed interest in the plight of gypsies. But only the Free Democrats, a free-market oriented party, has included them in their party platform. One Free Democrat supporter, a veteran dissident, notes the position and said wryly: “This support (for the gypsies) may be the kiss of death for the party.” He explained that prejudice against gypsies is so widespread that it may hurt the party to show sympathy for the group.

There are roughly 400,000 gypsies in Hungary–comprising 4-5% of the population. The official communist media has often linked them to criminal activity, and many Hungarians agree with this characterization. Gypsy advocates say that while one sector of the gypsy population is prone to live outside the law, the majority of Hungarian gypsies want to earn an honest living.

Gypsies have had problems with social acceptability since they left India, probably around 1000 AD. They aroused suspicions on many counts. As nomadic people, they relied on seasonal work in circuses or fairs. Or they accepted jobs that locals found distasteful. In Romania, for example, many became undertakers or dogcatchers. In Bulgaria, the job of hangman and executioner was often carried out by gypsies. It was not uncommon for gypsy women to tell fortunes, beg, or operate as con artists.

After World War II, gypsy men were cheap unskilled labor for the newly created state-organized economic sector, accepting jobs other Hungarians disdained. But as factories cut back workers as part of the new economic reform, the gypsies aren’t wanted in industry anymore. They are also an easy target: It is simple to sack gypsies: they won’t have trade unions stepping in to protect them, and they haven’t any other base from which to fight back.

In the Stalinist years, East Europe’s gypsies were forced to settle. All the Soviet-bloc countries created fixed-address laws which said it was illegal to live a nomadic life. There were other, more insidious campaigns against the gypsies. In Hungary, scores of gypsy children were taken from their parents to be trained as musicians, a traditional occupation for gypsy males. In Czechoslovakia there were periodic campaigns to sterilize gypsy women.

As harsh as these measures were, there were nothing new for the gypsies. In olden days, the gypsies of Eastern Europe were treated like animals, or worse. In the 16th century, gypsies were shot for bounty money. During World War II they suffered their own holocaust, with 400,000 perishing in concentration camps.

Today, Hungarian opinion makers see the gypsies as the country’s most stubborn social problem. They are the hard-core of a swelling underclass. With the spiraling prices, the ranks of the poor are growing quickly. “The situation is changing because impoverishment has started hitting people who up until now had a middle-class existence,” says Havas. “And these are people who are capable of looking after their own interests.”

Before World War II, Hungary’s poverty was so conspicuous that the country won the nickname, “the country of three million beggars.” With the installation of communist regimes after World War II, the banner cry was equality for all. But in truth, privilege and disadvantage were simply less talked about. One of the last subjects to be freed from censorship in recent months was the embarrassing question of poverty. After trying so hard to present Hungary as a communist showcase to the West, the ruling elite didn’t want the dark side of Hungarian life exposed.

Before the rise of free speech, social workers like Havas and Ladanyi were trying to press for change behind the scenes. They spoke out about the inequities under communism. “There is one class in Hungary that can afford all sorts of luxuries.” Havas says of the present situation. “At the other end we find people who can hardly have anything to eat.”

Some 20% of all Hungarians now live under the poverty line. If the disenfranchised were to unite, they would represent a sizable voting bloc. Though political analysts don’t expect such movement anytime soon, they see a growing awareness in the population of the power of protest. This winter, the homeless of Budapest showed just such acumen. They held a match to protest their eviction from train stations around the capital, and embarrassed the authorities into commenting on the problem. When the police came to shove them out of one station, the homeless collected all their identity cards, which every Hungarian citizen must carry as identification. They threw them in one pile and yelled to the waiting officers: come and get us–and try to figure out who we really are. Again the authorities were put off guard–and left them alone.

Now that social problems are openly aired, the public is shocked–and a little confused. Not long ago they were told the system would provide everything. “Now we learn that old people spend their entire winter in bed–to stay warm without heat,” says Mraia Herczog, a social worker in Budapest. “People are very tired and very fed up.” Social tension grows as living standards soar for about 1/3 of the population–mostly those in private businesses–and decline for at least 1/4 of the population.

The coming job layoffs will make matters worst, especially for the gypsies. Still, it will be up to them to make their own way, with very little help from the outside world. Even with the support of one political party, or more, change will come very slowly to this despised tribe, locked into a life of poverty and helplessness.

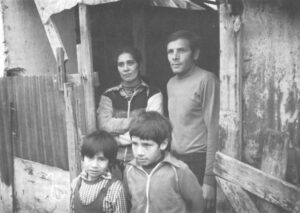

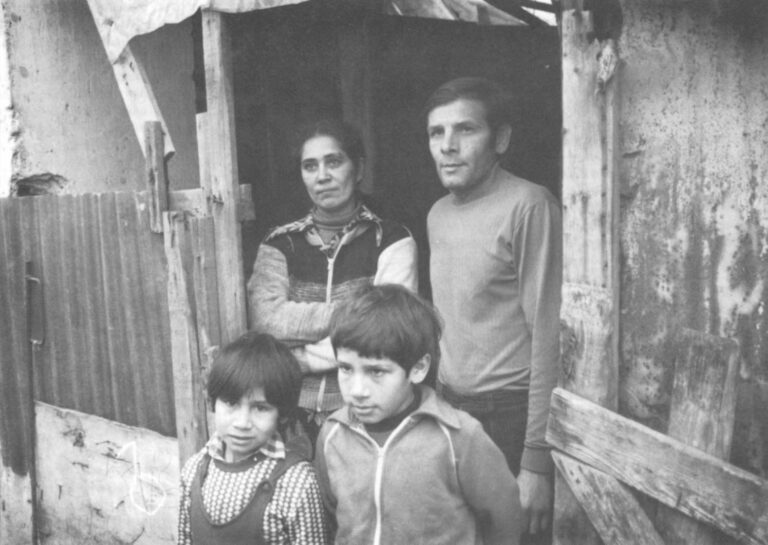

Such is the case in Miskolc. At the far end of the gypsy compound there, a couple greets their children from the front of their tin-roofed shack. With only one small window and no electricity, the house is always dark. The family tried to install electricity but the authorities say it isn’t possible. So a coal stove keeps the small space cozy. Years ago they applied for government housing. but it’s never come through. It seems inconceivable that these four can fit into this small hovel, built with nothing more than planks of wood and sheets of tin siding. The young children place their book bags carefully on a neatly made bed. Following a routine that may never change, they run to the well to get water for cooking the evening supper.

©1990 Victoria Pope

Victoria Pope, a freelance writer, is examining Eastern Europe in the era of Gorbachev.