May 15-20, 1989:

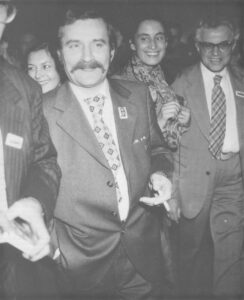

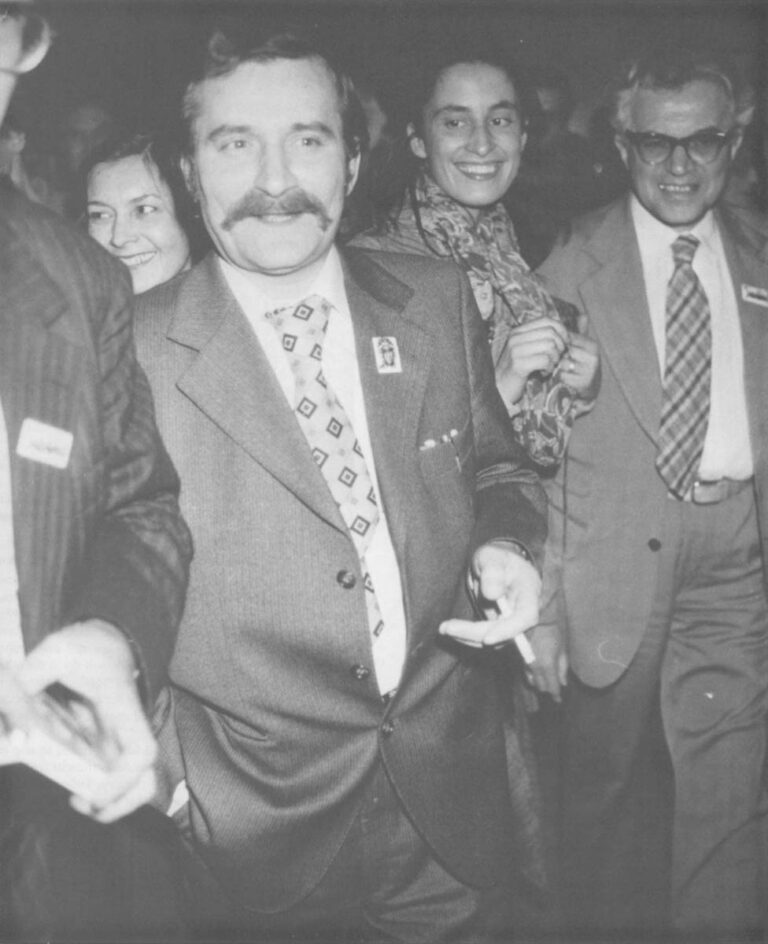

A week of highs and lows for Lech Walesa. In Strasbourg, France, the Council of Europe honors him with a human-rights award. In ceremonies there, he is accorded the protocol usually reserved for heads of state. Before Mass at the Strasbourg cathedral, the archbishop warmly greets the Solidarity trade union chief at the door. Then Walesa proceeds to Brussels, and meets with King Baudouin of Belgium. The talk barely gets underway when the awe-struck translator, a distinguished Polish intellectual, breaks down in tears.

By the weekend Walesa is back in Poland, visiting the provincial city of Bydgoszcz. He leads a rally to bolster support for the local Solidarity candidates competing in Poland’s first partly free elections since World War II.

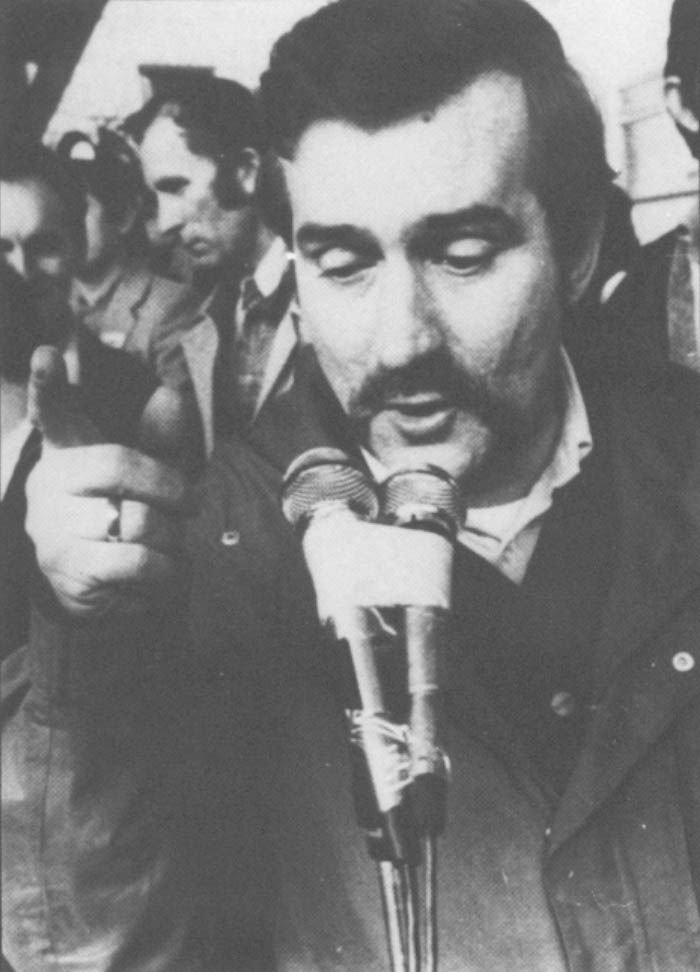

Walesa meets with Solidarity members for a pep session. He enters the meeting hall of Bydgoszcz’s cable-manufacturing plant to the welcoming chant of “Lechu! Lechu!” But in the left-front corner of the room, a low rumble of voices turns into high-pitched cries of “Rulewski! Rulewski!”

Clearly, Walesa hears the name of the long-time Solidarity militant, but doesn’t let on. It is not the first time Jan Rulewski, a political foe nicknamed “the pistol,” has fouled Walesa’s party. The man with the famous moustache doesn’t break pace, and keeps his arms aloft in the gesture of victory. Not until he takes his seat at the front of the room does his nodding, smiling face turn secretive, even sly. He lowers his chin, and his mouth turns to an expressionless slab. His nose does the talking. It wags disapprovingly like a bony finger. “I have three naughty places in Poland–Bygdoszcz, Szczecin, and Lodz,” he says, referring to certain cities where he faces heavy criticism. “But I’m particularly sorry to see the opposition here. This is the region where I was born.”

The crowd isn’t moved. An undertow of murmuring punctuated with taunts makes that clear. The workers are angry that some local opposition figures, such as Rulewski, weren’t picked as candidates for Parliament, and blame the union leader. Walesa steps up his appeal. He reminds the assembly that the murdered body of the blessed Father Popieluszsko was discovered not far from Bydgoszcz. He asks for unity in his name. But even this evocation fails to calm.

August 15-20, 1989:

Walesa holds a series of high-level meetings. In a stunning series of events, Solidarity has nominated him to be the next prime minister of Poland. One Gdansk-based reporter, a regular at the Walesa home, asks the union leader for his view of this amazing development. Walesa, stone-faced, answers mostly in pantomime. He draws a finger menacingly across his neck to mimic a throat-slashing. “That’s what will happen if I take it, and that’s what will happen if I don’t,” he says. Later in the week, he turns down the offer, and his advisor and friend Tadeusz Mazowiecki accepts the position. Walesa seems relieved. He declares his “political crisis” over, and vows to concentrate on the rebuilding of Solidarity, the trade union he helped forge when he climbed the Lenin Shipyard wall in August 1980, and changed the face of Poland.

WARSAW, Poland–A hand-written sign at Solidarity’s besieged headquarters here underscores its present-day dilemma: “We do not handle family or housing problems.” Telephones ring; many must go unanswered. It is difficult to help Poles get through each day and rebuild a nation at the same time. When visitors ask for help with the reading of a lease or in confronting a janitor, the overworked volunteers sigh, smile ruefully, and ignore the sign. In this tired and ruined land, Solidarity’s brief is by necessity wide.

In the decade since its birth, Solidarity has lived the great themes of life: victory, betrayal and vindication of its cause. Now comes perhaps the hardest part for the trade union and de facto political party. After years at the barricades, the trade union now seeks a less turbulent era of consolidating its base and organizing a platform. But the times are against it.

Months of fast-paced political change have given Solidarity strategists little time for long-range planning. They have become entangled in the here and now. As the leading party in a new coalition government, Solidarity has burgeoning political clout, but needs to learn how to use it. As a trade union it must become strong and cohesive, rebuilding its regional bases and regaining members lost during nearly a decade as an illegal organization. Caught between such large, and potentially conflicting duties, Solidarity in time will change, potentially even splitting into several entities.

But at the top of the agenda for both its politicians and trade unionists is the pressing problem of engaging a public that’s losing hope, even in Solidarity. Long gone are the glory days of Solidarity when the touchstones of martyrdom and common roots could galvanize a crowd. Gone are the days when the sight of Walesa alone bred respect and loyalty. For easy accolades, Walesa must go abroad.

“Solidarity was a huge national front against the totalitarianism and for the defense of human rights,” recalls Zbigniew Romaszewski, a Sejm deputy and member of Solidarity’s national executive commission. “When there was a question of basic rights–freedom of speech, of faith, of gatherings, of demonstrations–Solidarity was there, and all the groups were united. Now we have entered quite a different phase, a stage of solving very concrete problems. One can expect many new political groups. It will be more like a Western country.”

Though significantly strengthened by Mazowiecki’s election as prime minister, Solidarity has abiding frailties. In both its roles as political force and trade union, it is hobbled by a short supply of experts and organizers. Many of the able minds Solidarity counted on during its 16 months of activity in 1980-81 are now lost to the cause. Despondent over the crushing of Solidarity, some emigrated to the West. Others broke ranks and joined more militant groups opposed to what they call Walesa’s policy of accommodation with the Communist authorities. Still others have become lost to inertia, unwilling to take the plunge once more. “I got really very excited when the elections came around (in June),” says a leading Polish writer. “But then I saw that others around me weren’t very excited. It made me question my own commitment.”

The wait-and-see attitude of many professionals comes at an inopportune moment. For Solidarity needs good advice on how to stop the looming collapse of Poland’s economy. It is no longer a scrappy outsider trying to push its way forward, but a major player with the possibility of mounting a rescue plan–albeit against great odds. It will take great skill–and know-how–to change Poland’s bad economic habits and achieve labor peace. “Organizing a union that simultaneously defends workers’ interests and promotes economic reforms will be extraordinarily difficult,” Romaszewski muses.

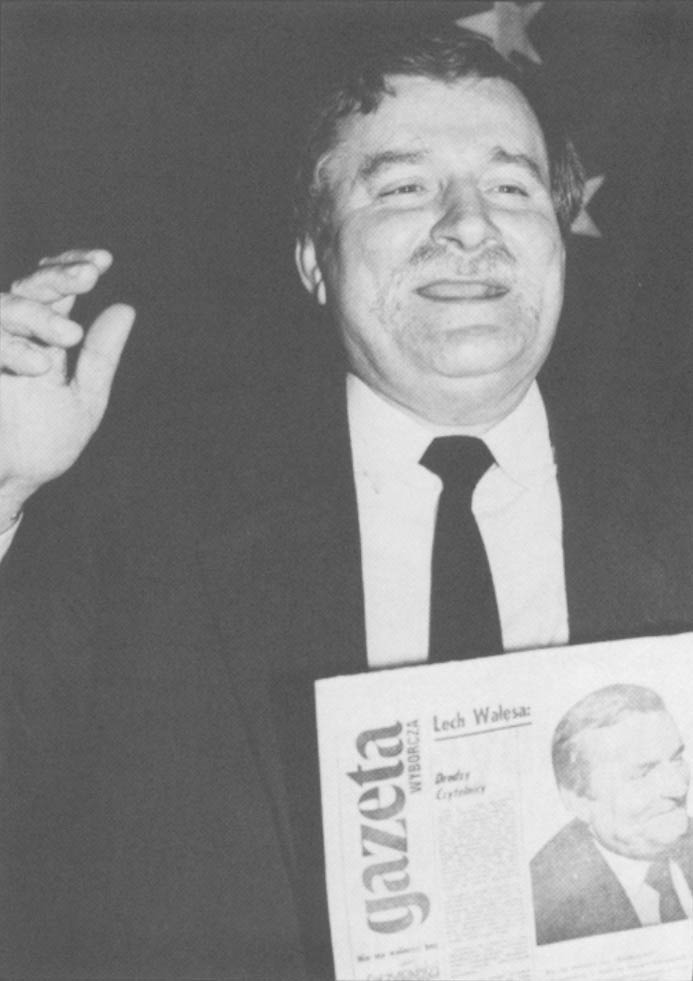

Capturing the interest of workers at a time of inevitable austerity will be hard. Since its legalization in April, membership to Solidarity has reached only one million, a far cry from the union’s 8.5 million card-carriers in 1980. Andrzej Celinski, a pro-Solidarity Senator and veteran Walesa advisor says one problem is simply that Poles learned over the years to live without a true trade union. Many workers will need strong reasons to come back. So far, the recruitment of new loyalists is moving slowly. Even the Gazeta Wyborcza, the Solidarity daily, hasn’t created a Solidarity union chapter after a half-year of operation. An editor there explains that staffers simply wonder if they have time for union activity on top of their other duties.

Solidarity needs a clear profile as a trade union to survive. But a sharply defined role will keep some old supporters away. “I’m a newspaper publisher, so I’m by nature against trade unions,” quips Marcin Krol, the chief of Res Publica, a weekly opposition journal. He is being arch, and not altogether serious, but his point hits home. Solidarity can no longer exist as simply an umbrella group under which all freedom-loving Poles rally. It must cater to the specific interests of working men and women. “I have a house in the country,” Krol continues. “So I am joining Rural Solidarity”–the farmers union.

The question of catering to labor’s needs has convinced many experts in and out of Poland that Solidarity would eventually reject a re-structuring plan that would force workers out of outmoded, inefficient industries into other areas of the economy. But such skepticism may be premature. In interviews, key Solidarity leaders such as Zbigniew Bujak and Wladyslaw Frasyniuk have stressed the need to shift from heavy to light industry. Asked if Polish workers–in the style of West German workers, for example–would balk at being forced to take new jobs in new cities for the sake of restructuring, both men insisted that such resistance would be lower than might be expected. Many workers are in fact the sons and daughters of farmers who were wrenched away from agricultural work during Stalin’s forced industrialization of the countryside, and do not have deep roots in urban neighborhoods.

But Solidarity should be expected to adopt many classic trade-union positions. At the roundtable meetings this spring between the government and the opposition, it pressed successfully for an indexation plan for workers’ relief. Even the most maverick of Solidarity’s economic planners have embraced the indexing of wages and pensions as the only way to stop the escalation of strikes and maintain social peace. Poland’s communist leadership, as well as many Western economists, criticized this option as an inflation booster at a time of already triple-digit inflation.

But strong labor politics alone won’t attract members to its ranks. With the emergence of freer speech and political pluralism in Poland, Poles are defining their political leaning more specifically. Once they had only Solidarity as a counter force to Communism. Now they have an increasingly sophisticated menu of groups to chose from, some of whom also claim to serve the needs of the working class.

Some of these groups have successfully wooed young, more militant workers away from the Solidarity fold. Most pesky among Solidarity outgrowth groups are Fighting Solidarity and the Working Group of the National Commission of Solidarity. The latter is comprised of Solidarity leaders who broke with Walesa in 1987. These groups accuse Walesa of bully-tactics, and say the union is undemocratic in its decision-making. Many Poles are cool to these renegades because of their strident, negative tone, and lack of concrete ideas. But their existence does highlight Solidarity’s loss of a widely based grassroots appeal.

“The working group and other dissidents within the union can be accused of many things: insufficient loyalty, inflammatory rhetoric, personal ambition,” the political commentator David Warszawski (a pseudonym) writes, “On the other hand, despite many virtues…the group centered around Lech Walesa seems to be losing its feel for society, its sense of what is non-negotiable regardless of strategic and tactical considerations.”

Solidarity’s union leadership fueled such grumbling when it dissolved the citizens’ committees, which were created after the April roundtable agreement. These committees shaped election strategy but also served as a valuable brain trust for Solidarity. The trade union hierarchy led by Walesa called for the disbanding of these units after the election. It was seen as a clear bid to eliminate the possibility of a dual authority within Solidarity. Some members of the citizens’ committees were openly annoyed by the move, and complained it was an obvious tactic to force them into mainstream union organizing, something they say they won’t do.

In a similar vein, Solidarity has been accused of trying to amass too much power at the top. In choosing candidates for their election line-up, the leadership decided to forego a primary-style nomination process. Indeed it selected candidates whom it viewed as the union’s best and brightest. It was, they often told their critics, a question of too little time to handle the nominations any other way. But open letters to the Solidarity leadership appeared in the press anyway. Their authors questioned whether Solidarity, as a front-line fighter for a democratic Poland, could afford to appear undemocratic in its internal decision-making.

Still, one young pro-Solidarity deputy, Jan Maria Rokita. downplays the damage done. “The emphasis should not be on who draws up the list of candidates from the opposition,” he says. “It’s how these lists are drawn up that matters,” he says.

These decisions have left tensions between the union and its political allies. Rural Solidarity, also legalized as the result of the roundtable, admits to awkward relations with its union partner. “Solidarity considers us a competitor,” says Jacek Szymanderski, part of Solidarity’s parliamentary bloc and spokesman for the farmers’ union. He says worker Solidarity is already pressing its demand for parity between worker and farmer incomes. While workers on average still make more than farmers, Solidarity is afraid the scale will tip in the other direction, Szymanderski says. But Rural Solidarity, which is pushing for full-blown market forces in the agricultural sector, is demanding attractive incentives and doesn’t want to see any such controls.

With its new political vigor, Solidarity is bound to step on toes. But it can’t afford too many dissidents from its ranks at a time of increased militancy in the country. Independent and government social scientists agree that more and more Poles want to take matters in their own hands. The Polish government institute for research into public opinion says that 10 percent of the population desires a violent confrontation with the authorities. Another 20 percent expect such a confrontation. These are arresting findings in a country which has been notably non-violent throughout its history.

Solidarity perhaps once could have stopped the splintering into many political groups, or quelled its rebels. But today groups such as the strongly anti-communist Confederation for an Independent Poland (KPN); the pacifist, anti-draft Freedom and Peace, the Polish Socialist Party and smaller anarchist factions are true competitors for the hearts and minds of Poles. Even within the center of Solidarity different political postures are coming into relief. Within Walesa’s circle, for instance. potential factions are forming. They include Christian Democratic leanings, which Mazowiecki represents.

Given these differences, a Balkanization of Solidarity may become inevitable. Indeed. as the new parliament becomes an arena for democratic politics, the legislators who came from Solidarity may openly oppose the union in certain issues. Some already have balked on the question of price indexing. One leading Solidarity figure in the Sejm admitted that he voted the straight Solidarity line–that even striking workers who won pay raises should be included in price indexation relief–because the union told him to, not because he believed it was best for the country.

Such loyalty is still ingrained. But as the political climate becomes more fluid, new allegiances are emerging. Solidarity leaders themselves admit such change is healthy. They say that many of the older Solidarity leaders who directed the activities of the underground opposition during martial law prize loyalty too highly–acting like old partisans who stayed too long in the hills. With bonds forged in eight years of clandestine life, loyalty to individuals and to conspiracy itself became a raison d’etre. “In the underground you can’t really build an organization,” says Wladyslaw Frasyniuk, a top Solidarity leader who was a key force in the underground movement. “In particular, you can’t build a democratic structure. For conspiracy limits peoples activities and experiences.”

Those first-generation Solidarity activists had only 16 months experience in running a legal organization before martial law struck. Coming out from the catacombs, they must learn the vocabulary of an open political culture. “There are some who have been active for seven years and now, for the first time, they have the chance to address people at meetings,” says Wladyslaw Frasyniuk. “It’s a real shock for them.”

Another jolt for these old-timers is the rise of a new breed of union activist. “The present leaders of Solidarity on the shop floor are very different from those in 1980,” Frasyniuk explains. “Then, they were well-educated workers, skilled workers–almost all had secondary school education. Now the level of education is much lower. People of higher education like engineers and technologists–do not enter these activities.” Frasyniuk straddles these two groups. Though he has a secondary-school education, his first job out of school was as a driver for the Wroclaw transport department. From there, at age 26, he was catapulted into the union’s national presidium. But his greatest fame came during his time on the run from the authorities. He earned a reputation in the underground for leadership and bravery.

Today Frasyniuk is one of the few Solidarity leaders who also can bridge the enormous gap between the average Polish worker and the intelligentsia. Workers find him unpretentious and mild-mannered. Intellectuals like his native intelligence and steady reasoning. Most important, Frasyniuk enjoys the trust of Walesa, who privately has dubbed him his heir-apparent.

But for now, amid the country’s apprehension about the future, Walesa commands the center of the stage. His role as mediator between the communist status quo and the opposition invites criticism. But more often than not. Poles call him a great man, and a cunning political operator.

Speaking from the stage at Bydgoszcz, Walesa succumbs to a fit of pique, referring to himself in the third person. Lech Walesa is tired. Lech Walesa wants to go home to his daughter’s first holy communion. But he holds back saying what is also perfectly clear: Lech Walesa has seen this all before. Lech Walesa would rather be anywhere else in the world but here.

Bydgoszcz for Walesa brings back memories of the difficult, fractious route to consensus within the union. Walesa’s bobbled handling of the “Bydgoszcz crisis” of 1981, when several local Solidarity leaders were beaten by police, was a turning point for the union. Walesa and Rulewski go back a long way. Rulewski was one of his union hotheads–one of the leaders which pulled the union inexorably towards clash after clash with the communist authorities. He symbolized the threat within Solidarity which weakened the union through interline battles. At the Solidarity national congress, Rulewski openly broke with Walesa.

Walesa suffered Rulewski in those days. But he no longer has to mince words. In an open-air rally in Bydgoszcz, Walesa tells thousands of supporters that Rulewski, quite plainly, betrayed him. “I’m unhappy about some people who are trying to break us up,” he adds. “Later we can break up. But today we have only beachheads of democracy–we need to stand together.”

Rulewski, too, gets his turn before the workers. Shouting, he accuses Walesa and Solidarity of heavy-handedness. He says he was excluded as a candidate on purpose. Walesa retorts with a voice that’s either full of pity, or mocking pity. “Jash, I could never count on you,” he says. “You had good days and bad days.” Rulewski and his followers rear up again, with fresh accusations. In the end, Walesa doesn’t back down, but shakes Rulewski’s hand. Rulewski looks close to tears. Walesa leaves, saying as he often does, “Let’s do something for Poland.”

Solidarity’s great gains of the last dramatic months may well mean it will indeed, do something for Poland. But no one, especially not Walesa, would deny that there are a multiplicity of fires for the union to put out. To be sure, Rulewski is a symbol of Solidarity’s feudal, even primitive side. But he is also an ever-present reminder of the importance of rudimentary loyalty on the plant floor, and the finesse Solidarity requires as it tries to forge ahead, leaving some of the union’s loose cannons behind.

Solidarity faces an enormous task to bring a suspicious and isolated public into the political arena. Even now, with political power in its grasp, the healing process for Solidarity has only just begun. “Our former freedom lasted 16 months and people aren’t eager to place things in public view–like their printing machines–just in case of a change,” says Zbigniew Romazewski. “This complex of conspiracy will last for a long time.”

©1989 Victoria Pope

Victoria Pope, a freelance writer, is examining Eastern Europe in the era of Gorbachev.