Text and Photos by Victoria Pope

BOJARY, Poland–in this cluster of small villages near Bialystok, Poland, there is a funeral every month and a wedding every two years.

The planting cycle, like the life cycle, is out of kilter. Though it’s harvest time, fields aren’t cut. Others tracts left fallow are overrun with wildflowers. Roads that should be abuzz with tractors are silent. Most all the local farmers are wasting their day in the gasoline line trying to buy fuel for their idle machines.

Bojary’s main street is empty. The only immediate sign of life is the clothesline. It tells a story of poverty and old-age on the Polish farm. The clothes–rags really–are tatty and limp as they wag in the hot summer wind. Not even the blazing sun can bring form to them. Flesh-colored stockings with lead-colored streaks hang next to patched overalls, checkered handkerchiefs and black shirtwaists threadbare to a flat grey. There’s nothing frivolous, nothing new, and nothing for the young.

About 40 percent of the Polish population still live in villages that usually aren’t much larger or better-off than Bojary. But only 27 percent of all Poles actually make their living from agriculture. This proportion is much higher than in many Western countries, but it is a far cry from the 1920’s, when Poland was Europe’s breadbasket and 70 percent of its population worked in the agricultural sector.

Farming, though in decline, remains a key sector of the economy. As Western traders and bankers try and pinpoint new business in Poland, they are giving agriculture special scrutiny. It is an ideal guinea pig for Poland’s ongoing efforts to create a market economy. With an overwhelmingly private base–most of Poland’s farms are owned by individuals–agriculture can respond more quickly to reform measures than, for example, the country’s shipyards or coal mines developed as key components of the socialized, state-owned industry. For all of agriculture’s deficiencies, there is less to undo, and great potential for success. “If the billions that were pumped into industry had been pumped into agriculture, Poland might be a lender nation today,” asserts a Western diplomat in Warsaw.

Fueling a green revolution in Poland calls for willing foot soldiers. But they won’t be found in the northeastern village of Bojary. Many of its houses are abandoned. Their owners have fled to the city. What remains are 25 farmers, all old, keeping the village going.

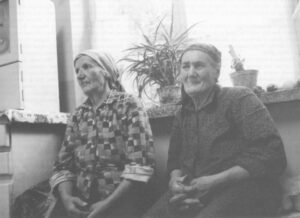

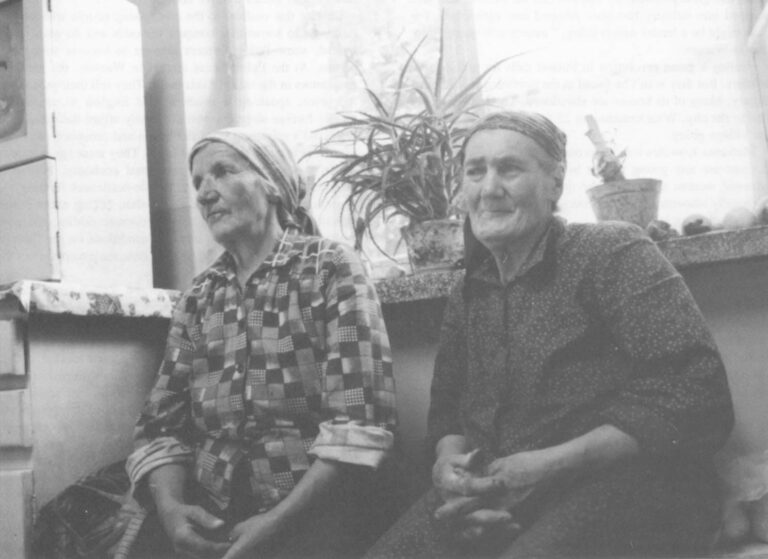

Marianna Kowalewicz, 78, is one of the oldest. When asked if there are any young people in the town, the bowed and wizened woman mulls over the question for some time and eventually answers: “Yes, of course, my son Henryk.” Henryk Kowalewicz is 53.

Mrs. Kowalewicz is almost blind, and painfully crippled. A dull blue bandanna is wrapped tightly around her head. She walks with her back at a 90-degree angle to her torso. She complains that the imported medicine needed to soothe her eyes is no longer available through the local clinic. The foreign medicine turns out to be nothing more than common eye drops available in any Western pharmacy.

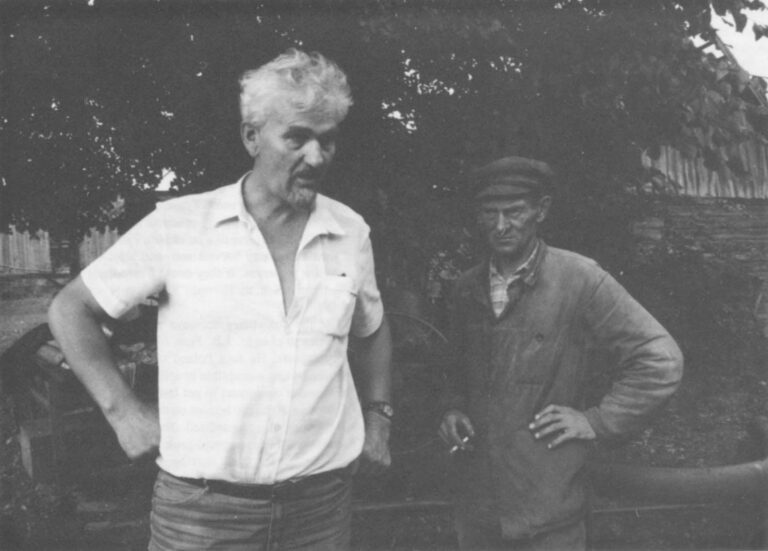

She worries about her son. His right kidney was removed not long ago and he hasn’t been well since. But the farm is an unrelenting taskmaster, and illness is no excuse. The pair rise at 4:30 am. to milk the cows and begin a long day.

The punishing schedule, the pair’s illness, and their poverty have conspired to turn their stone cottage into a ramshackle hovel. Next to the kitchen’s coal-fueled stove, cracked enamel pots are strewn about. Wilted leaves of cabbage teeter under a wooden stool. Nearby lies an empty can of goulash. From a ledge under the dirt-streaked window, a statue of Saint Andrew blankly surveys the chaos.

And yet, Mrs. Kowalewicz says she has seen worst times. “The most difficult was the 1950’s,” she recalls. “The children were just small, and the men came to the house and made me spill out all in my jewelry box. Then they would call us rich kulaks”–landowners.

“Rich!” she exclaims. “In those days, I felt it was not worth it to live.”

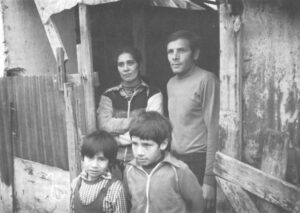

Not all Polish farmers suffer as much as the Kowalewicz family. Not all Polish farms breed such deep poverty and sickness. But this image of farming is typical enough to prompt thousands of young people to flee rural living. One of the greatest challenges facing new Poland’s leadership is to stem this depopulation of the countryside, and give incentives to go back.

Jan Beszta-Borowski, a Rural Solidarity leader from the nearby village of Borowski says one basic problem is image. It is all too common to hear life on the farm berated. “You’re considered an idiot if you want to stay on the farm,” he says. “It should be the other way around.”

Still, it’s easy to imagine why they leave, first the young women, then the young men spurning an inevitable bachelor-hood. They get sick and tired of cold water from a well, crockery that’s never quite clean, and running to the out-house in the middle of the night. It’s normal for women to give birth at home, and return to return to work in the fields posthaste. In the face of this grind, the urban high-rise and an eight-hour factory shift means relative comfort.

Despite this outflow to the city, young people who stay in farming can sometimes conquer the odds and do quite well. Indeed, some Polish farmers manage to become very prosperous. At the Polna Street market in Warsaw, the peasant-proprietors in the stalls fit this mold. They sell their produce at top price, speaking a smattering of English to please the mainly foreign shoppers who can easily afford the outlay.

Poland’s reformers want the bustle and prosperity of Polna Market to extend to farming at large. They want agriculture to act as the workhorse of an exhausted economy. Economic planners are searching for ways to “de-bottleneck farming,” a favorite phrase of the World Bank when talking about Polish agriculture. While solving these economic riddles, the government will also need to improve conditions on the farm so that the Kowalewicz family will become the exception not the rule.

The basics, too, have to be achieved. Polish farmers don’t know how to hold a livestock auction. There is only a primitive system of grades and standards. And there isn’t a formal publication of prices–so that farmers must rely on their own experience and hearsay to set prices on the private market.

But they have learned how to air their complaints. Last spring, Poland’s farmers carried out protests that pressed the government to bring forward the long-planned deregulation of food prices. “It was a spontaneous expression of outrage,” says Beszta-Borowski, recalling the protests which took place in Lapy, near his home. Beszta-Borowski said the farmers were angry with the milk cooperative’s manager because the milk they were supplying to the dairy was constantly downgraded. As a consequence, they were getting paid less and less. When the group confronted the manager about this apparent inequity, he told them: “I don’t need your milk. You can throw it in a ditch for all I care.” And so they did. “One farmer picked up the milk container and threw it into a ditch,” Beszta-Borowski explains. “Five thousand liters of milk went into that ditch and the strike spread to other facilities.”

In the wake of these protests a “marketization” policy was implemented on August 1st. It removed fixed prices on all foods except plain bread, low-fat milk, soft cheese, and some baby foods. It also ended the formal rationing of food. These risky measures were introduced in an effort to stimulate the farmers to produce more food, and to keep them quiet. Prices of meat nearly tripled, while price rises for sugar, butter and flour ranged from 40-75%. The increases are being offset by wage raises for workers, but they are still hard for the urban population to swallow.

Peasants flexed their muscle in other ways. Following the roundtable accord in the spring of 1989, Rural Solidarity–the farming arm of the trade union Solidarity–was re-legalized along with a package of other key reforms. These accords between the communist government and opposition groups ushered in more democracy. Testing its new-found clout, the head of Rural Solidarity, Josef Slisz, proposed the creation of a new party, the Polish Peasant Party-Solidarity, which would rival the United Peasants Party, a long-time ally to Poland’s Communists.

The United Peasants Party, though discredited in the past, has lately been showing teeth. It played a crucial role when it switched allegiance to Solidarity, thus creating the parliamentary bloc that allowed Tadeusz Mazowiecki to take over as prime minister in August 1989. The end-product was the first Eastern bloc administration led by a non-communist since Stalin consolidated control of Eastern Europe after World War II.

Rural Solidarity assumed a new era of peasant politics was dawning, and was disappointed to see it wasn’t quite so. The farmers’ union received only one post of minister without portfolio in the 24member cabinet, despite its long alliance with Solidarity. The Mazowiecki government has tried to smooth the ruffled feathers, but the basic tension–between rural and urban interests–remains.

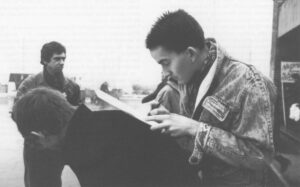

This time, the countryside is fighting back. Back in 1980, Rural Solidarity frequently kowtowed to labor Solidarity which led the famous workers strikes. But this time around the two groups are more evenly matched. “We are getting strong, and we are not terribly attractive to Solidarity from this point of view,” says Jacek Szymanderski, the spokesman for Rural Solidarity. Szymanderski, who is also a member of Parliament, notes a political zeal among young farmers reminiscent of the short-lived flowering of the trade union Solidarity in 1980. “The village lags ten years behind the city,” he says. “The generation of young electricians who started Solidarity, we are beginning to see them now on the farm.”

The dilemma for the new government is to keep these two power blocs happy. Farm and factory are often at cross purposes in Poland. While farmers view the rise in produce prices as a meager step in their rebirth, industrial workers at the other end of the ledger showed their anger at the price increases by striking throughout Poland. And while farmers are claiming that the first months of regulated prices haven’t improved their lot yet, urban dwellers are outraged over the skyrocketing prices.

A bar of butter which cost the zloty equivalent of five cents in summer costs the equivalent of half a dollar by autumn.

Such prices are an exorbitant outlay in a country where an average month’s salary is $15. Even before the August price hikes, Poles were spending a disproportionate amount of their disposable income–as much as 65%–on food.

The spiraling prices has forced a drop in the consumption of many foodstuffs, some as much as 40%. Whole milk, for one, has become prohibitive. When its price was deregulated, the cost of a liter jumped to 900 zloties. The price of skim milk is still set by the state and costs 30 zloties a liter. People buy skim milk when it’s available. Otherwise they go without, but not without smoldering resentment. They blame farmers, and complain without real evidence that farm children are getting fat while the city kids go without the basics.

The mood is explosive, and experts hope the food relief on its way to Poland from the United States and other countries will help ease tensions. Yet even this help could hurt farming if it’s not handled carefully. “Extreme care must be taken to ensure that the donations do not become counterproductive,” agriculture expert J.B. Penn told the Committee on Foreign Affairs at the U.S. House of Representatives. “There could be potentially adverse effects”–over- supply and bottlenecks in the “very fragile” fledging market structures.

The establishment of a smooth-running supply and demand mechanism is central to the success of the new government. Through it, Poland’s new leaders might balance the needs of the farmer with the needs of the urban consumer. Solidarity hasn’t fooled itself into thinking that the people will stand by them at all costs. In the long run, Poles will only support a government that can give them food and stable prices.

The government’s concern is supported in recent Polish history. Indeed, the dearth of food supplies was the target of rage during the Baltic shipyard strikes which ushered in Solidarity. The last five communist governments have fallen because of food shortages. There is even a saying epitomizing the importance of food: “Polak jak glodny zly,” or “When Poles get hungry they get angry.”

And yet the shortages could turn to abundance. Western experts visiting Poland say the farming sector can be turned around. A team of international experts led by Dr. Norman E. Borlaugh–the architect of the green revolution in Mexico–recently toured Poland for the second time in seven years to assess the prospects for agriculture. The group reacted with that combination of despair and general optimism which often afflicts outsiders trying to make sense of the Polish situation. They were cautious yet positive about the potential, pointing out that the agricultural science base is quite impressive. But they estimated that private farmers are achieving only 50-70% of the genetic potential of crops and livestock.

There’s even a hope among the experts that weaknesses might be turned to advantage. Poland’s farming is organic–not by design but often due to shortages of artificial fertilizers. Might this be a window of opportunity, some planners ask. They cite the growing market for health foods, especially among Northern Europeans. But Gregory Vaut, the director of the non-profit Foundation for the Development of Polish Agriculture, adds a proviso: “In the health food industry you depend to a very large extent on packaging and marketing–two areas where Poland has a lot to learn.”

Poland also has possibility of developing labor-intensive crops in the fancy-food category. These might include wild mushrooms, game and berries for export. The World Bank has designed a possible project along these lines called the Forest Product Plan.

Even modest reforms would perk up certain produce lines overnight. For example, 25 percent of all potatoes grown in Poland are spoiled because of poor storage and inadequate processing. And there are no facilities for freezing the potatoes for french fries, a potential export. Then 40,000 tons of apples are fed to pigs instead of making juices-because bottling plants are closed.

The strawberry is another case of unmet potential. Poland is the number two strawberry producer in the world-but it earns only 20% of the price of a jar of jam. Farmers crush 70 percent of their strawberry harvest and send a lot of it to West Germany for preserves. If they could freeze them immediately or sell them fresh to Europe, they would enjoy worthwhile profits.

But the strawberry scenario also illustrates some of the obstacles to change. J.B. Penn offers a warning about strawberry exports. He says Poland still packs its strawberries in wooden boxes, susceptible to splintering. All that is needed is for Western consumers to get huffy about swallowing a piece of wood or about the bruises on the berries, and Poland would have its business jeopardized. To really compete they need to use state-of-the-art vacuum-pack packaging which would prevent the berries from moving against each other and stop bruising. That kind of packaging is expensive, and not likely to be used in Poland anytime soon.

Polish farming has many other antiquated features to overcome. The average tractor is 15 years old. Most farms have only a hand-pumped well for water. In fact, the pitiful state of the rural water system is widely blamed for the slow progress in livestock production. Only 22% of private farms are attached to a local water system which can guarantee more or less clean water. Less than half of all farms have mechanical water intake. Some 7,000 out of 40,000 villages in Poland still have frequent water shortages.

The dairy industry is another area woefully in need of modernization. As it exists today, the system is almost counterproductive. When a farmer milks two cows, he puts the milk at the side of the road where it often turns sour before it is picked up. When it’s tested at the central milk packaging plant, the bacteria count is often high–leaving it unfit for human consumption. So it is added to pig slop instead.

This lack of modern features hurts exports. A year ago, Poland lost three million dollars worth of business selling rabbit meat to Great Britain, France and Germany. The reason: the European Community said that Poland violated trade requirements that say all meat for export to the EC must be kept in cold storage of a certain size. Since Poland didn’t have this equipment, it prohibited further imports of this meat. While some observers view the incident as nothing more than backhanded protectionism, it illustrates nonetheless Poland’s vulnerability in trying to build up its agriculture.

Playing catch-up alone won’t be enough. A Polish official proudly told a member of the Borlaugh mission that the country would be self-sufficient in the manufacture of cans by 1995. That Borlaugh team member, an expert in food processing and the new plastic packaging, felt compelled to deliver a depressing truth. “By then you will be the only country still producing in cans,” he told the official.

The other great restraint is the continuation of monopolies. Despite the ballyhooed “marketization,” the bulk of grain is still bought by the state grain monopoly; the same goes for milk and several other important commodities. Though the state is allowing the prices to go higher in many cases, the structure is still that of a command–not a market–economy, explains Rural Solidarity’s Szymanderski.

Farmers say market forces must become much stronger if they are to profit from the procurement price increases. One farmer outside Warsaw calculated that he has to use to use 400 kilogrammes of dry fodder and 600 kgs of potatoes to breed one 100-kilogramme pig. At the new prices he receives 1,150 zloty per kilo of livestock. When he adds up the cost of feeding the pig-according to the new prices–not counting the cost of coal needed to prepare the fodder and his own labor–then he is still running at a loss.

Given this harsh reality, there is the constant temptation which many farmers succumb to–to bypass the purchasing station and sell the livestock to free-market sources for much higher prices. This practice hinders a normal pattern of selling and buying. That irregularity translates into dire shortages.

It wasn’t always so. From the 16th and l7th centuries onward, Poland was not only providing for itself, it was a prosperous exporter of rye, corn and wheat, sent on merchant ships from Gdansk harbor to ports in Western Europe. When the communists took over at the end of World War II, the old commodities exchange was shut down. The space became government planning offices. “We want to see the commodities exchange building revert to its old use,” says Jacek Jancelewicz, a member of Solidarity’s national presidium. Many Poles hope that what remains of the old agriculture infrastructure might be resuscitated in this era of new beginnings.

But it will take some doing. During the collectivization under the bloody rule of Josef Stalin, many village mills and other local food processing facilities were shut in favor of large regional depots. The authorities tried ruthlessly to “urbanize” the countryside as part of their propaganda to create a workers’ state.

There is no greater paean to this destructive policy than Huta Im. Lenina, the vast metallurgical works and town outside the southern Polish city of Cacow. It was widely considered by the post-war communist leadership to be the greatest achievement of the new Poland. But the complex was a bitter reminder to the peasantry that the authorities believed farm land was better used as the site for a steel mill than for rows of crops. The mandate of Nowa Huta–new steel mill–was to create a new urban working class. Even today, many workers at that plant live on farms which they tend on weekends and evenings, living mainly from their blue-collar incomes.

These modern day worker-farmers are the children and grandchildren of private landowners who fought against great odds to hold on to their property. Between 1946 and 1966, some 800,000 peasants were jailed for refusing to collectivize, according to Wieslaw Kecik, a former advisor to Rural Solidarity. Strangely, throughout this brutal period, peasants were often reassured that they would be able to continue private farming. But it was clear to the peasants that the government was rapidly instituting a policy that would make agriculture secondary to industry. In 1938, 2.73 million persons were employed outside agriculture. By 1948, that figure had climbed to 3.5 million.

Part of the problem goes, back to communism’s roots. The scholar M.K. Dziewanowski traced anti-peasant prejudice directly to Marx: “Karl Marx, a city boy with little knowledge of life and work in the countryside, had a thoroughly negative attitude toward peasants.” Dziewanowski wrote, quoting Marx as saying that one of capitalism’s achievements was that it saved the modern proletariat from the idiocy of rural life.

The regime of Edward Gierek, from 1970-80, deepened rural hostility toward the government. Prices for grain and other agricultural products were held at artificially low levels, while the prices for farm equipment were exorbitant.

Beszta-Borowski, 54, now a member of parliament from the Bialystok region, is one farmer who lived through the worst of times–but never considered leaving agriculture. His life story reflects the hardships facing peasant activists over the last 45 years.

His first brush with controversy came in 1946, when he was ten years old. His teacher told the class to write about Polish-Soviet friendship. Beszta-Borowski said what he believed–that Poland was under Soviet occupation. Though he and his parents were severely reproached, he went on to other battles. At the height of Stalinism in 1951-52, he and other friends established a “White Eagles” club to publish tracts against collectivization and communism. His punishment was first a 3-month detention, then a sentence of two and a half years in prison. Later, he failed to follow orders to “show grief” at the death of Polish leader Boleslaw Bierut. That heresy caused his expulsion from school, but he managed to take courses sub rosa through the kindness of a teacher. When drafted, he was sent to the mines to work because he was officially termed a “public enemy.” It was so hot down the shaft that all the miners had to work naked, and dump the water out of their boots several times a day, he recalls.

Beszta- Borowski’s harassment didn’t let up. Many jailings followed. These were the days when even being late on delivering “your quota” of grain was deemed a crime. All the private farmers felt the heat, Beszta-Borowski says, and many grew despondent. “People began to feel a hatred toward the land,” he says. “They began to give up–and sold their land to the state in exchange for a pension.” Between 1950-1955, the number of collective farms rose dramatically from 12,513 to 28,955.

The rise of Rural Solidarity helped to ease the fear, but the trauma of collectivization lingers. In July 1983, a constitutional amendment was enacted which protects peasant property. This move was a boost to farmers, though few failed to notice that while the individual sector is “protected,” the state sector is “developed and strengthened,” according to the amendment. Farmers remain suspicious of any government–even a Solidarity-led one.

For there lingers a feeling in the countryside that no one cares and that no one really champions their cause. Mrs. Kowalewicz, visibly pained to walk down the front steps of her home, shuffles as fast as she can to say goodbye to an American visitor. Tears spring from her half-closed, rheumy eyes. “Thank you for coming–Thank you for caring about our poverty,” she cries out, adding in bitter afterthought: “But won’t Americans laugh at us? I hope they won’t laugh at us.”

©1990 Victoria Pope

Victoria Pope, a freelance writer, is examining Eastern Europe in the era of Gorbachev.