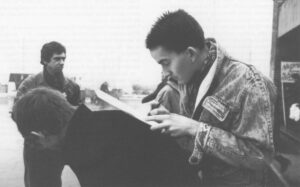

ESZTERGOM, Hungary–For more than 20 years, Istvan Horvath sifted and searched for Hungary’s buried treasures: ancient gold coins, altars, arches and urns. Were it not for the bulldozers on the banks of the Danube, he would have gone on digging peacefully for another two decades. Instead, he has excavated against a deadline to try and compress a century-load of work into five years.

Those hovering bulldozers, and their role in building a hydroelectric dam on the Danube River at Nagymaros, near Esztergom, propelled the soft-spoken Horvath into opposition politics. The archaeologist and museum director pinned the blue and white button of the Danube Circle environmentalists to his coat lapel. On the double-height, Hapsburg-period door leading to his office he tacked up a poster declaring: “Stop Nagymaros.” Off-hours, Horvath wrote letters and essays repeating that conviction.

Not long ago, such partisan activities would have been out of the question for an employee of Hungary’s communist state bureaucracy. But over the last year, the authorities have espoused a new openness which has eased press censorship and allowed opposition groups. The crusade to stop the dam brought together poets and pianists, scientists and parliamentarians, engineers and historians, all emboldened to speak out in this new climate. Still, Horvath’s fight against the dam was not without consequence. He wouldn’t be explicit, but said stoically: “I was rebuked.”

His activities, though still risky, have fresh chances for success. Hungary’s leaders recently announced a suspension of all work on the dam, at least until midsummer. During this moratorium, the government is assessing the cost and other impacts of halting the project once and for all. They are trying to smooth over differences with Czechoslovakia and Austria, partners in the project. Though the environmental opposition isn’t shouting victory yet, it acknowledges a great leap forward. For even if its cause suffers a setback, the movement to stop the dam has reached the high ground. It has transformed the relationship between dissidents and the authorities in Hungary.

That relationship was already changing as the nation began to freely debate communism and its future. The system faces harsh interrogation, one question leading to another: Why should the communist East have shoddy construction, neglected old landmarks, and bad air? Why should there be no funds for fixing these problems? Why do communism and economic bankruptcy seem to go together? “In socialism, you open the door, and you don’t know what to fix first,” said Csaba Pasko, an architect-turned-environmentalist, with an impatient shake of the head.

The Nagymaros project became a symbol of communism’s inhuman face. “The dam is a constellation of the most terrible things this system has created,” said Gyula Kodolanyi, one of the country’s most important poets. With grave, gray eyes, a cap of white hair, and a sparse eloquence, he appears almost monastic. Indeed, he has meditated long and hard on the dam: “It’s the best visible collection of the errors of the Stalinist economy–it absolutely ignores the interests of the individual, of the small community; it ignores national considerations as well as aesthetics.”

Kodolanyi lent his respected name to the stop-the-dam cause, and penned a stirring defense of the celebrated river that flows from the Black Forest mountains to the Black Sea. In it, he evoked the power of historic association–those images that become emblems of a country. At the Danube Bend, site of the Nagymaros dam, the river is “majestic, gently turning and made vivacious by the play of light,” he wrote. “The water almost touches our feet, and we are lost in the mesmerizing bustle of immobility and motion, perspective and proximity, while the noises of civilization impart greater profundity to silence.”

Critics like Kodolanyi linked the dam to the misguided past, when progress under communism meant wholesale disregard for nature, or as French writer Andre Gide once warned of that system, “plowing straight furrows in a curving field.” The 1950’s were the heyday of this mentality. Factories were deliberately placed in wheat fields and smokestacks were exulted in art and slogans. Generations of Hungarians remember being lectured that the Soviet Union’s master scheme to change the flow of two Siberian rivers was “the miracle of communism.” (Under Gorbachev, Moscow has decided to reconsider those river diversions.)

Such memories stirred resentment toward the dam. They lured some establishment politicians into environmental politics. One communist-party member of Parliament, Gyula Bubla, outspokenly took up the Nagymaros cause. “This dam is the last symbol of the Stalinist era, and we must try and fight against it,” he said. Mr. Bubla is one of about 50 parliamentarians who publicly opposed the project, especially criticizing its cost–$1.5 billion and upwards. Parliament was first reformed in 1984, when openly contested elections were held. It still is top-heavy with communist party members, but many legislators, cutting a new profile, are talking about their duty to constituents.

This parliamentary opposition included Janos Szentagotai, a former head of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Szentagotai, a blunt, old-school intellectual who wears suspenders and French cuff shirts, isn’t a party member. He won a loyal public following when he blasted the government in a speech calling for a stop to construction. “The reason for our present difficulties is that we discussed such things as the dam in strictest secrecy behind closed doors,” he said in a televised parliamentary debate. The legislature voted overwhelmingly at that time to accept the government’s report supporting the dam. But Szentagotai’s speech, because it reached such a large audience, was a shot in the arm to the environmental movement.

Behind the scenes, other key officials had their doubts. One member of the Central Committee of the Hungarian communist party recalls his own attempts to oppose the scheme in closed sessions–before the present political thaw. It was hard to convince his colleagues that “It was alright to be a communist and an environmentalist at the same time,” he said.

But the times held promise. Last spring, the long-reigning party chief Janos Kadar was ousted by Karoly Grosz, who proclaimed a new era of greater liberty. Hungary has always been in the vanguard of communist reform, but Grosz did one better, upping the ante at a time of glasnost in the Soviet Union. Since Grosz took over, taboo subjects, such as what happened during the Hungarian revolution of 1956, have been open to probing debate. Dramatic revisions of the constitution, including the legal formation of more than one party, are in the works.

Environmentalists thought the dam, too, would enjoy unfettered debate. But the government was until very recently strangely taciturn about it. Officials would point out with a shrug that there isn’t much new to say about a fait accompli. Yet several prominent politicians, such as the prime minister Miklos Nemeth and leading party reformer Imre Pozsgay. paved the way for a change of position, first saying they would support a national referendum to vote for and against the dam, a long-standing demand of the opposition. Their behind-the-scenes lobbying for a halt to the project brought the issue to a head. In mid-May, a deputy to Nemeth announced the suspension of work.

The many months of apparent intractability reflected deeply rooted habits and fears. Several key Hungarian communist party figures, including Grosz himself, embraced glasnost with much fanfare but perhaps without deep conviction. They found it hard to unlearn the reflexes of their political caste. These professional party apparatiks were schooled in the principle of “party prerogative,” making their collective judgment inviolate. Even today, about two-thirds of all central committee members are holdovers from the Kadar era, when the dam project was finalized. It’s not surprising that this group remains wary about the decision to suspend construction.

Even some reform-minded leaders were reticent to explicitly criticize the dam. They are afraid too much frank talk on the issue will split the party and precipitate a lasting schism between its conservative and liberal wings. This anxiety appears well-founded. The reform wing of the communist party has made clear its disagreement with Grosz’s pace of change. They wanted it faster, and pressed for the government to suspend dam construction. This move called into question Grosz’s authority, which has grown increasingly shaky. Reformers were angered by the party leader’s heavy-handedness in suppressing discussion and press coverage of the issue.

In the early 1980’s, the dearth of factual information about the dam sparked political derring-do. A 1981 article by a science writer named Janos Vargha boldly attacked the dam complex as a wasteful environmental blunder. Thus the movement had its first manifesto, and Vargha went on to become the leader of Hungary’s first unofficial ecology group, Duna Kor–The Danube Circle. The Danube Circle gathered steam quickly, and in 1985 it won Stockholm’s Best Livelihood Award, the so-called alternative Nobel Prize.

This opposition started as a minor irritant, then became a direct challenge to the system’s one-party leadership. But there was a price to their growing celebrity. The group was censured in the establishment press. Their activities grew perilous. Around the time of a planned “environmental walk” against the dam in February, 1986, police called in Danube Circle members and threatened them with violence if the protest went on. The group, seeking to avoid a bloody confrontation, called off the walk, but the news didn’t reach all the interested parties. When a small group, including some Austrian protesters, gathered on the appointed day, police forcibly stopped them with rubber truncheons. The incident was a sober reminder of the limits Hungarians environmentalists faced. Later, with improvements in the political climate after Kadar’s ouster, public rallies were again tried. These pressure tactics culminated with a massive demonstration against the dam in the fall of 1988 in Budapest. That protest was a particularly triumphant moment for the opposition because it was carried out with the full permission of the authorities.

By the time that demonstration took place, the Danube Circle was no longer alone at the barricades. The reform spirit in the country sparked the creation of many new opposition, or alternative, groups. The roster grew quickly, with environmental associations leading the way. Besides the Danube Circle, the movement spawned the Nagymaros Committee, university action groups, and ecology sub-committees of The Hungarian Democratic Forum, the Federation of Democratic Youth and the Alliance of Free Democrats. Even a division of the Esperanto Club concentrated on environmental affairs.

These groups reflected growing environmental awareness. Community action, long an anathema to the rigidly controlled power structure of the communist party, was on the rise. Citizens began speaking out about such hazards as toxic waste and certain kinds of manufacturing, like dry-cell battery-making. They successfully fought Austrian plans to dump the garbage of Graz across the border in Hungary. And villagers in Ofalu and Mecseknadasd, near the southern city of Pecs, managed to force the suspension of nuclear waste dumping near their community.

It’s no wonder that Eastern Europeans are worried about their corner of the planet. Chernobyl forced hard questions to the surface. What’s more, the region is markedly polluted. Many east bloc factories have inferior emission controls. Cheap automobiles with “two-stroke” engines, which run on a mix of oil and gasoline, spew out a choking, foul exhaust. Acid rain destroys forests, ancient monuments, and even burns holes into clothing left out to dry. Heavily industrialized areas like Silesia in Poland, and North Bohemia in Czechoslovakia have high rates of lung cancer and respiratory disease. Tap water can be dangerously dirty. Some Western embassies warn their diplomats with babies to bathe them in imported water while living in Poland. In Czechoslovakia, stores give families with newborns priority rations for bottled water. What makes matters worse, these economically strapped countries can’t easily afford high-tech pollution controls.

Politically, the authorities in the Soviet bloc don’t know quite what to do with environmental action. It’s worrisome to party conservatives because it has potential to draw in the silent majority. It attracts individuals like Istvan Horvath who might otherwise avoid politics. Once involved, these individuals become networks, which develop into groups. They canvass neighborhoods, give lectures and talk to friends. Arpad Fasang, a Hungarian concert pianist, tried organizing in a novel way. He wrote to protestant ministers at churches near the Danube, urging them to oppose the dam from the pulpit. Many picked up on the suggestion.

“We put pressure on the government this way,” recalled Laszlo Solyom, a law professor who helped the early environmentalists with legal matters. “In earlier days, the environmentalists had to fight to exercise fundamental rights. But they tried, and tried, and tried again. This contributed to the present situation, where these activities are now legal.” Almost from its inception, the Danube Circle had sought out the lawyer in his corner office at Budapest’s Lorand Eotvos University. Here the pale, bespectacled professor would sit among the glass-doored cases filled with leather-bound volumes and give advice. Solyom became crucial to the movement. For he had written a legal tract published in the official press that would help the opposition. In it, he maintained that any action not specifically illegal was possible.

This distinction changed the way protesters did business. Before that, the practice was to ask for specific permission for each and every activity. Now they tried spontaneous demonstrations. But testing the system this way quickly caught the attention of the security forces. Some were pressured by police to renounce their activities. Janos Vargha was forced out of his job at a popular-science magazine. “That was the heroic age,” Solyom said.

Nowadays, environmental politics are more in the mainstream. Some 140,000 Hungarians signed a Danube Circle petition for a referendum. Though the official press tried to discredit this effort, charging for example that teachers get their young pupils to sign, the campaign was a success.

“These signatures are only paper to this government,” conceded environmentalist Laszlo Vit. But Vit was convinced that press attention alone makes the activity worthwhile.

Given this level of public visibility, it’s perhaps inevitable that the Danube Circle would lose its old solidarity. Hit by infighting and petty politics, many of its early trailblazers left, taking their political experience into other arenas. Hungary’s new political climate sparked conflicting strategies. Some of the Danube Circle wanted to test the waters of glasnost more boldly and become more active as a political unit. Others, like Vargha, wanted to stick to science. At meetings, disagreements dissolved into name-calling and threats to resign. “Yes, sharp rivalries started,” Solyom confirmed, and added with a laugh: “Many of the old partisans have retired.” Even the press spokesman for the Danube Circle, Andras Skekfu, was blunt about the divisions among the different environmental groups. “We don’t want a lock-step image, like a ministry,” he explained. “But we can’t have silly and dangerous people in our own lines.”

Despite these differences, they united to oppose the dam, which would affect a 50-mile stretch of river north of Budapest. The dam construction site is situated at the village of Nagymaros, in a richly historic neighborhood. Facing high bluffs above the Danube Bend where the ruins of a splendid Renaishhed, some 24 Roman watchtowers dot the river to its north. The environmentalists’ worries centered on what would happen to the wetlands when the Danube, under the conditions of the original plan, was to be expanded to flood a 15,000-acre reservoir and then rerouted into a sealed canal in Czechoslovakian territory.

The plan included two dam sites, one on the Czech side at Gabcikovo, the other at Nagymaros. But in a bid toward Realpolitik, most of Hungary’s ecologists weren’t pressing for a halt of the Gabcikovo dam, which was close to completion. They targeted Nagymaros, a 30-minute drive from Budapest, where roughly 10 percent of the work was finished. The dam here, they argued loudly, would flood forests and small islands, ruin the habitat of 200 species, and pollute drinking water.

Much public questioning of the project focused on its cost at a time when the authorities are asking for economic sacrifices. Hungarians wondered why the government would push a new scheme, to host a Budapest-Vienna exposition, with this dam already taxing the budget. Hungary has the highest per capita indebtedness in Europe, rising inflation, and a worsening trade balance. Average people are suffering, and are increasingly willing to vent spleen. They hold two, three jobs just to cope with the spiraling consumer prices and newly introduced personal income taxes. “When you pay a lot of tax, you become a conscientious citizen overnight. You ask: ‘where is my money going?’” said Gabor Sule, a Budapest magazine editor.

Austria’s role also made the dam’s opponents angry. They saw a cynical purpose: after all, Austria tried to build a hydroelectric dam at Hainburg, but was stopped by its environmentalists. Vienna and a consortium of banks gave Hungary a 7 billion schilling loan, roughly $600 million. The loan was to be repaid in electricity, so that, beginning in 1995, Austria would have had most of the energy generated for about 20 years. And Austrian firms won almost 80 percent of the contracts, sparking complaints that Hungary has let itself play the poor cousin, falling back into old habits learned in the days of the Hapsburg empire.

International groups tried a carrot-and-stick approach. The Environmental Policy Institute in Washington, D.C. pledged to intercede with international lending institutions to ask them to pay the expenses of freezing the project. Other groups joined in. “The dam would be worth nothing to the Hungarians in 20 years,” said Owen Lammers, the administrative director of International Rivers Network in San Francisco.

In the aftermath of the suspension order, the government began investigating these offers of help. But many officials, who were forced to defend the plan to an increasingly hostile public, clearly feel defensive. “Never forget, we are not traitors to this country,” Istvan Miko, the project’s chief engineer, blurted out impulsively.

Even the state waterworks officials, wary of the public, took pains to appear flexible, even before the project was suspended. Horvath recalled that they extended some of his deadlines, and allowed him to redraw blueprints. “These relics are as much relics of their past as our past,” he admitted.

But goodwill alone wouldn’t give him the time he needs: “We would need a hundred years to do the archaeological work by high professional standards.” And when construction was still at full tilt, there were the inevitable accidents. Horvath can’t help wincing in the telling. At one site, a Roman age grave was discovered too late–when a bulldozer inadvertently excavated it. Suddenly bones and a skull poked out of the churned earth. On the remains of an ear lobe, a gold earring was smashed beyond repair. The other earring, facing downward, was saved. “I’m of course very sorry when such things happen on a large scale,” he said, pausing to cough. “Yet one gets used to it.”

If the suspension order sticks, Horvath will return to normal pace of work. If it doesn’t, he has an emergency priority list to save first from destruction the Helemba Island, with its Celtic and Arpad ruins.

The immensity of Horvath’s job is daunting. Esztergom was once a big city–in the Middle Ages, it was twice the size of today. “Of European magnitude,” Horvath said, his voice rising. And he knows how Esztergom and the vast Danube are inextricably linked in a turbulent past: the first traces of neolithic culture along its banks, the town’s glory days as the ancient capital where the first king of Hungary, Stephen I, was born and crowned; then the hard-luck of Mongol invasions, and more than 140 years of Ottoman occupation.

From his apartment on Katona Street in Esztergom, he can hear the water lapping against the quays at night. By day, he can see the river through the window near his desk at the Balint Balassi museum. As a small child he lived on the far bank, in the Hungarian town of Parkany. When he was six, at the end of World War II, he and his family fled across the river to Esztergom. His native village, small change in the treaty of Paris, was turned over to Czechoslovakia.

He recalled the bombs that seemed to split the sky. “I still hear the sound of battle in my ears,” he said, looking stunned more than 40 years later. It’s such images of triumph and loss, and the sharp messages they convey, that made many Hungarians willing to oppose the colossal dam-construction project.

What’s left of their country–two world wars truncated its old boundaries–needs protecting, they say.

Such calamities have buried many artifacts all around and deep underground. Excavations, ongoing since before World War II, have reached the 15th century level. Horvath agonized over the still-untouched 13thcentury level. For somewhere there lies the grave of good king Bela IV, who presided over Hungary’s rebuilding after the Mongols wreaked havoc. “If the ground level water rises even just a little bit because of the dam, we won’t be able to study these very important, deeper lying levels,” he said furrowing a deeply lined forehead. “This is what is most painful. This is our chief complaint.”

The grave of a medieval king was perhaps a strange point of departure for years of unflinching opposition politics. But Horvath knows enough history to understand the call to heroism. By the door of his office, he paused to contemplate a huge, dark bell, streaked with lines of verdigris. Nine hundred and fifty years old, it is the oldest bell in Hungary. It gives out a deep, low rumble when he strikes it. Found by some modern-day farmers plowing a field, records show that the bell was buried in ancient times. Research indicates local peasants were worried by the approach of the fierce Ottomans. They knew the Turks would melt the bell to make guns, and buried it down deep, far from harm’s way. “They all died,” Horvath said. “But the bell has survived.”

©1989 Victoria Pope

Victoria Pope, a freelance writer, is investigating Eastern Europe in the era of Gorbachev.