The tobacco industry is forging new, behind-the- scenes relationships in its effort to polish its image and to fight smoking bans and excise taxes. In a public relations fantasy come to life, the $35 billion-a-year industry has aligned itself with organized labor and black, Hispanic and women’s groups, whose civil rights rhetoric and appeals for social justice have a special resonance in American life.

Ample supplies of ingenuity and cash are being lavished on these allies, for whom tobacco money may buy anything from scholarships and entertainment to printing and legal services. For an industry that still insists that smoking isn’t a proven cause of illness, and that cigarette ads aren’t meant to increase smoking, these friendships can help restore lost credibility.

With sympathetic allies as point men in the tobacco wars. the cigarette makers can spend more time behind the lines. Take the case of a slickly-produced booklet telling workers how smoking rules can be “a smokescreen” to avoid safety improvements and liability for industrial disease.

“Remember, although he may say he only has the workers’ best interests at heart, when he’s talking about smoking policies, a boss is still a boss,” warns the booklet, which bears the seals of five big union s–including the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers and the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America.

The only seal missing belongs to the group that bankrolled the guide: the Tobacco Institute.

A brochure sponsored by the American Agriculture Movement attacks excise taxes on cigarettes, fuel and other goods as unfair to small farmers. Only AAM is named on the brochure, which was co-authored and printed by the tobacco industry.

In 1986, when Congress considered banning discount sale of cigarettes in military commissaries, the American Logistics Association issued a study on how the move would rob military personnel of part of their benefits. Few, if any, readers could have known the author was a tobacco industry consultant.

In the old days–when states and city councils left tobacco pretty much alone, and senior southern pols repulsed the few attacks in Congress–such creative liaisons weren’t needed. Today, the industry must try killing foes with kindness–as it has, for example, by showering money on fire prevention groups to blur cigarettes’ status as the leading cause of fatal fires.

“‘The all-powerful tobacco lobby’ is better characterized as the very wealthy tobacco lobby,” U.S. Rep. Charles Rose (D-North Carolina), observed in an interview. “It’s powerful and it pays its way, but it is a different kind of operation than it was fifteen, twenty years ago…because tobacco’s got more problems in this town than it ever had before.”

To meet the threat, individual companies–particularly industry leader Philip Morris (Marlboro, Benson & Hedges, Virginia Slims, Merit) and number two RJR Nabisco (Winston, Salem, Camel, Vantage)–supplement the lobbying of the Tobacco Institute, which represents five of the six leading cigarette makers and several smaller tobacco firms.

Founded in 1958, the institute has a staff of 100 in Washington and several regional offices–and a budget that topped $29 million in 1986, according to disclosure forms obtained from the Internal Revenue Service under the Freedom of Information Act.

The institute issues brochures, reports and videos, lobbies Congress and state legislatures, and sends industry-paid experts–whom it calls “truth squads”–on cross-country media tours to debunk the risks of second-hand smoke.

But these days, the big push is for “coalition-building”–which often involves financial help to groups whose pro-industry stands are cited as evidence of independent support. Brennan Moran, media relations director for the institute, said the tactic only bothers the industry’s enemies. “I don’t think there is anything sinister,” she said. “It becomes an issue only if you want to look at the tobacco industry as…one that shouldn’t help groups promote a message that coincides with ours.”

The outreach to labor has been a particular triumph, according to an internal Tobacco Institute memo describing a Florida meeting of AFL-CIO leaders in February, 1987.

“When we attended our first AFL-CIO midwinter meeting three years ago, we found a majority of labor leaders and their staffs openly hostile to the industry,” the internal memo reads. “Our reception earlier this week, at our third meeting, could not have been friendlier.”

A Tobacco Industry Labor-Management Committee, founded in 1984 and financed by the Tobacco Institute, is the glue for this alliance. Of the five unions on the committee, only the Bakery, Confectionery and Tobacco Workers International Union has a big stake in tobacco, with 17,000 tobacco workers among 135,000 members. The other four–the machinists, sheet metal workers, carpenters, and firemen and oilers–together have less than one half of one-percent of their members in the industry, according to figures supplied by the unions.

The workplace smoking guide–which describes ulterior motives for smoking rules–was a committee project. In recent years, it also has contributed about $3,000 a month, or nearly 15% of the budget of Citizens for Tax Justice, an influential labor-backed group that supports higher income taxes on business and the wealthy and opposes excise taxes on a variety of goods as unfair to workers and the poor. (State and federal excise taxes, which are sales taxes amounting to about one-third of the price of a pack of cigarettes, cut down cigarette sales).

“It falls in the category of ‘politics makes strange bedfellows,’” said David Wilhelm, former executive director of Citizens for Tax Justice. According to Wilhelm, if tobacco companies “want to join us in talking about the regressivity” of excise taxes, “I think we’d be crazy” to spurn their help.

In a creative move, the industry secretly has combined a jobs program for its labor allies with its campaign to deflect attention from the problem of second-hand smoke. Using Tobacco Institute funds, the National Energy Management Institute (NEMI)–a joint venture of sheet metal contractors and workers–is training workers to detect indoor pollutants (other than tobacco smoke) and to prescribe ventilation improvements–which naturally would be installed by sheet metal workers. The Tobacco Institute, which refused comment, is providing about $100,000, a NEMI spokesman said.

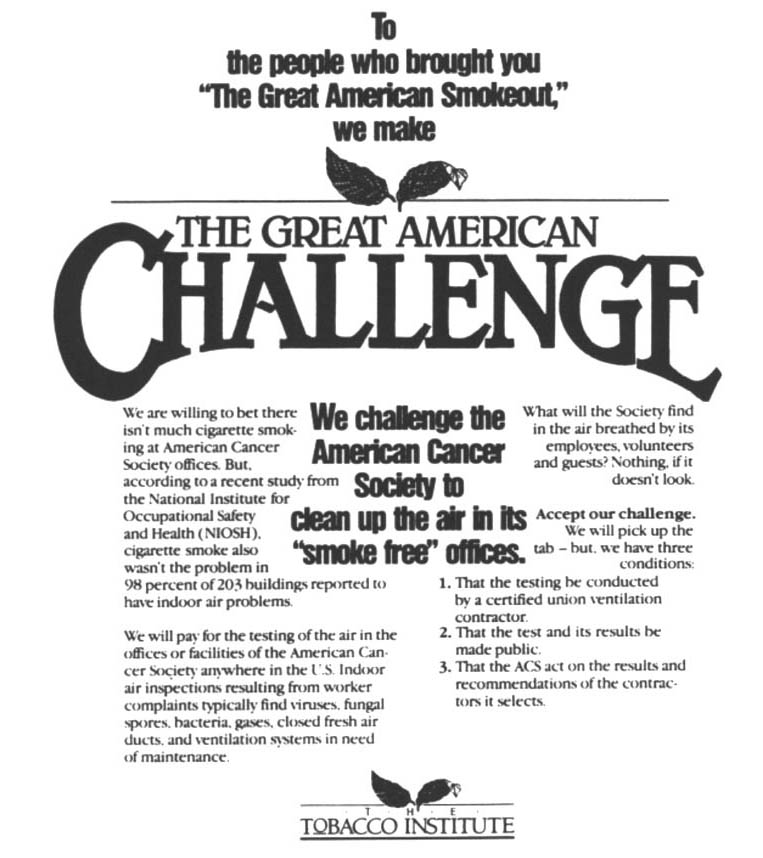

The gambit figured in the industry’s attempt last November to upstage “The Great American Smokeout,” the American Cancer Society’s annual appeal to smokers to quit for a day. In its widely-advertised counter-event, “The Great American Challenge,” the industry offered to send “a certified union ventilation contractor” to any cancer society office to check for “viruses, fungal spores, bacteria, gases, closed fresh air ducts, and ventilation systems in need of maintenance.”

The “certified” union contractors were identified in an internal memo–but not in the full-page newspaper ads–as “any member of our ally, the National Energy Management Institute.”

“If the (American Cancer Society) does accept our challenge,” the memo reasoned, “it is likely that the contractors will find problems with ventilation and air quality–particularly given the fact that nonprofit agencies generally rent offices in inexpensive and under-maintained buildings.” As luck would have it, no cancer society office responded to the offer.

Such efforts sometimes backfire, as occurred last September, when full-page ads in New York papers attacked a proposed smoking ban on commuter rail lines in the name of a transportation union. The campaign, which cost about $80,000, was paid for by Philip Morris, whose name did not appear in the ads. The ploy was denounced by Advertising Age and Newsday, which blasted the “tobacco company’s duplicitous campaign.”

Also last September, 14 unions took out ads against proposed excise tax hikes. The Progressive, one of the magazines that published the ad, blistered it on a separate page for failing to disclose that the money came from the Tobacco Institute.

Ray Scannell, a tobacco workers union official, defended the industry’s behind-the-scenes role.

“Generally, the people who are flaying us over it are…people who have a grudge against the tobacco industry,” Scannell said. If you suggest tobacco companies are “not equivalent to the oven tenders at Auschwitz, you get vilified.”

According to Scannell, the anti-excise tax ads used industry money to push “the line that the labor movement has always pushed…So who’s using who?” he asked.

Matthew Myers, staff director of the Coalition on Smoking OR Health, an anti-smoking group, retorted, “If it’s not dirty money, why are they (the cigarette companies) so far in the background?

“There’s no message that can be totally separated from the speaker,” Myers said. “That’s why we’re entitled to know who the speaker is.”

With the action on smoking laws and taxes shifting to the states, the industry has opened its purse to state legislative associations–and closely watched for every anti-smoking nuance. In 1987, tobacco contributions to four of these associations exceeded $250,000–an estimate that does not include tens of thousands of dollars of in-kind support, such as free legal work and golf and tennis tournaments at annual meetings.

The National Black Caucus of State Legislators, which represents more than 400 black state lawmakers, last year got more than $60,000 in donations from Philip Morris, RJR, and the Tobacco Institute. The institute also helped revamp the group’s computer system. The caucus’ general counsel last year was Ronald White, a lawyer for the Tobacco Institute in Philadelphia. White said he avoided conflicts by not advising the caucus on tobacco issues. The picture of former caucus president and ex-Maryland state senator Clarence Mitchell III graced an institute excise tax brochure until Mitchell was charged and later convicted in the Wedtech scandal.

David Richardson, a Pennsylvania lawmaker and current president of the National Black Caucus, said tobacco contributors want a chance to talk to lawmakers, “just like all the companies that we…have associations with.”

The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), an alliance of 1,700 conservative state lawmakers, receives about $50,000 a year from the tobacco industry, which also sponsors golf and tennis events and pays ALEC’s bills at Covington & Burling, the industry’s powerhouse Washington law firm.

A recent ALEC symposium on indoor air pollution was funded by the industry and dominated by its paid experts. But Constance Heckman, executive director of ALEC, sees little chance of conflict.

“We are conservative, we are pro-business,” she said. “They (tobacco companies) don’t change us. They just compound our effectiveness on the issues that we agree on.”

The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) and its affiliate foundation–which last year got at least $65,000 in tobacco support–saw industry lobbyists come unglued over a study on hospital cost containment in 1985.

Two former staff members said NCSL officials caved in to industry pressure to delete statements about the health costs of smoking from drafts of the study. “Money spoke to the people who ran the organization,” said Nancy Shanks, a former employee of NCSL who worked on the study.

NCSL officials contend that they did not dilute the report to suit the industry. They could not find working drafts to compare with the final study, which contains brief references to smoking as a cause of health problems.

Philip Morris and the Tobacco Institute recently helped fund an NCSL report generally critical of “earmarking”–the practice of dedicating revenues from specific taxes for health care or other needs. Earmarking builds political support for new taxes and so is zealously opposed by the tobacco industry.

The industry helped out because “I assume that they thought the report would be useful,” said Steven D. Gold of NCSL, a principal author. “The people from the tobacco industry knew what economists in general would say about earmarking, and I’m an economist,” Gold said.

The Council of State Governments, which receives at least $75,000 a year in tobacco contributions, made do with less in 1986 when it was punished by the industry after hosting a conference on indoor pollution. Industry-paid consultants ,served as panelists, but tobacco lobbyists complained the program was stacked against them. Tobacco companies withheld their usual donations to the council’s eastern regional meeting, according to industry sources and council officials.

Tobacco money–long a mainstay of some black groups–now is a growing force among women’s and Hispanic groups. These groups received at least $4.5 million from the industry in 1987.

Leading the way were Philip Morris and RJR Nabisco, which account for nearly 71% of U.S. cigarette sales. Both companies have diversified into food and other goods. But cigarettes–among the most profitable of all legal products still provide the lion’s share of their earnings–and the unsavory image the gifts are meant to erase.

Philip Morris, best known for its lavish support for the arts, gave over $2.4 million in 1987 to more than 180 black, Hispanic and women’s groups or local chapters, according to Tom Ricke, chief spokesman for the company. This excludes gifts from the company’s General Foods subsidiary, which are distributed by a separate foundation.

RJR Nabisco gave $1.9 million to 49 minority and women’s groups and institutions last year–not counting gifts from local RJR operations, company officials said.

In a Martin Luther King birthday speech to black college presidents on January 18, RJR president F. Ross Johnson described the image-enhancing role of corporate contributions. “Anyone can make a profit in the short-term,” Johnson said in the Atlanta speech, “but we are thinking about profits ten years from now as well, and good citizenship is just as important an investment as research and development.”

To critics, however, the industry is simply buying “innocence by association.” They say cigarette marketing gets a boost from the link with minority and women leaders–those luminous examples of mobility and success that are staples of cigarette advertising.

The industry’s generosity is of special concern to health groups, because women and minorities have been slower than white males to kick the habit–and thus are the industry’s best hope of reviving flagging sales. Cigarette billboards are ubiquitous in some minority neighborhoods, and Philip Morris has become the single biggest advertiser in Hispanic media, according to a survey by Hispanic Business magazine.

According to latest evidence, lung cancer has surpassed breast cancer as the leading cancer killer of women. Today a higher percentage of blacks smoke than whites, and blacks die at a higher rate from lung cancer and coronary heart disease, both smoking-related. Despite these trends, the health toll from smoking is not high on the agenda of many women’s or minority groups.

In 1987, tobacco companies gave at least $350,000 to the black, Hispanic and women’s congressional caucuses or their affiliate foundations–mostly for fellowships for minority and women students and for dinners and social events.

The Congressional Black Caucus Foundation received more than $175,000, the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute received more than $65,000, and the Women’s Research and Education Institute (WREI), an affiliate of the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues, got more than $100,000.

“I simply think it’s part of their way to make themselves look better,” said Alison Dineen, fellowship director for WREI. “They know that they’re perceived negatively by representatives who are concerned with health issues…

“To tell you the truth, I’m not that interested,” Dineen said. “I’m just glad they fund us.”

The National Women’s Political Caucus received $130,000 last year from RJR and Philip Morris, according to officials of the companies. Tobacco gifts account for 10% to 15% of the group’s budget, caucus chair Irene Natividad recently told The Boston Globe. A national directory of women elected officials was produced last year by Philip Morris, which has compiled similar directories for black and Hispanic groups.

Like many other beneficiaries, the women’s caucus rarely takes formal stands on smoking or other issues, so the industry gets no immediate payback. But as members ascend the political ladder. they are good people for a besieged industry to know. Victoria Leonard, who heads the National Women’s Health Network, which does not take tobacco money, called the gifts “an investment in people” who may be “more willing to listen to a tobacco lobbyist five years down the pike.”

Tobacco support for Hispanics has increased with their numbers and buying power. Philip Morris has sponsored leadership training programs for Hispanic women in New York, and last year gave $150,000 to the U.S. Hispanic Chambers of Commerce. Tobacco money also goes to the National Council of La Raza, the League of United Latin American Citizens, the National Hispanic Scholarship Foundation and the National Association of Hispanic Journalists.

“Philip Morris gave us money and hasn’t asked for any special consideration,” said Frank Newton, executive director of the Hispanic journalists group. “I’m less concerned about taking money from Philip Morris…than the fact that a lot of these big media companies don’t give a dime.”

Tobacco firms have been among the only steady national advertisers in black papers and magazines, and the industry has courted the black press in other ways as well. In 1985, Philip Morris brought dozens of black publishers to New York for a two-day meeting, which was addressed by Hugh Cullman, then vice chairman of the firm. According to a published account, Cullman told the black publishers:

“Today, tolerance for my smoking may be under attack. Tomorrow, it may be tolerance for someone else’s right to pray or choose a place to live. So the real issue isn’t smoking versus non-smoking–it’s discrimination versus tolerance.”

RJR funds journalism scholarships through the National Newspaper Publishers Association, a black publishers group that named RJR its 1985 “Advertiser of the Year.” When the first Black Journalism Hall of Fame induction ceremony was held in Baltimore last fall, the keynote speaker was Stanley Scott, a vice-president of Philip Morris.

A favorite tobacco charity is the United Negro College Fund, which last year got $267,000 from RJR, $32,000 from Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., and $120,000 from Philip Morris. Cullman, who recently retired from Philip Morris, is the chairman of the college fund.

Cigarette companies gave more than $400,000 in 1987 to the National Urban League, which has honored past Philip Morris chairmen at its annual “Equal Opportunity Day” dinners. Former Urban League president Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., is on the board of directors of RJR Nabisco. Margaret B. Young, widow of former Urban League head Whitney Young, is on the Philip Morris board.

Clarence Wood, vice-president for external affairs of the National Urban League, said taking tobacco money does not contribute to “what is perceived as the negative impact of cigarettes on the minority community.” Woods said, “We have not seen it as any attempt to hold us prisoner or buy us off.”

Brown & Williamson, the number three cigarette maker, honors five inner-city leaders a year with “KOOL Achiever Awards,” named for the B&W brand that is a leading seller to blacks. The company donates $50,000 to non-profit, inner-city services designated by the honorees.

The industry has won considerable gratitude from many recipient groups, who point out that their support comes from a wide array of industries.

To critics, however, tobacco gifts are unique in scale and in legitimizing a business whose products, according to the U.S. Surgeon General, cause 1,000 premature deaths a day in the U.S. “They’re avoiding the image of death peddlers, and instead are becoming the champion of the downtrodden,” said Anne Marie O’Keefe of the Washington-based Advocacy Institute.

As critics see it, minority groups generally have avoided the smoking issue, and the industry wants to keep it that way. Unable to address every worthwhile cause, they naturally will be leery of one that carries a heavy financial risk.

“It’s preventive medicine from their (tobacco executives’) standpoint,” said Dr. Alan Blum, a cofounder of Doctors Ought to Care, a health advocacy group.

Some beneficiaries are similarly uneasy. Black groups are being “co-opted,” said Paul Ruffins, editor of the Congressional Black Caucus’ quarterly magazine and a former advertising man. “As a propagandist, I can see what’s happening, Ruffins said. “Black and poor people are being used in propaganda wars that have nothing to do with them.”

But tobacco officials say the pummeling would be worse and more deserved–if they failed to share their wealth.

“Would it be better that we not make those donations?” asked RJR spokeswoman Janice Cousart.

“If we gave $1 million to Mother Teresa, they’d (industry critics) find something wrong with it,” bristled Tom Ricke, the Philip Morris spokesman. “We do it (contribute) because it’s the right thing to do.”

Complaints about tobacco support for blacks go back to the 1950s–when, ironically, the critics were white racists. According to the companies, the record shows they backed minorities before it was fashionable and before smoking came under siege.

In the 1950s, for example, white supremacists called for a boycott of Philip Morris brands. According to The White Sentinel, a supremacist monthly:

“Philip Morris Inc. has the worst race-mixing record of any large company in the nation. Its President, Joseph F. Cullman, is a member of the Board of Directors of the National Urban League …Philip Morris was first in the tobacco industry to hire Negroes instead of Whites for executive and sales positions…Philip Morris was the first cigarette company to advertise in the Negro press.”

Worse still, the White Sentinel reported, Philip Morris helped produce a travel guide for blacks–a “vicious booklet” explaining the public accommodation laws of each state.

But foes are not persuaded. “The cigarette industry has known for more than 30 years that they were selling a lethal product and walking on a political time bomb,” said Myers, of the Coalition on Smoking OR Health. Thus they long ago “began to cultivate non-traditional allies.”’

But have these friendships really helped the cigarette makers? Despite their efforts, the smoking habit–once widely accepted and even admired–is fast becoming a sign of weakness and disregard for others. Coalitions may not restore smoking’s falling social status. But allies are crucial in the legislative wars.

There’s a wide misconception that the industry loses each time an anti-smoking measure is introduced. According to the Tobacco Institute, of 468 anti-industry bills (proposing smoking or advertising restrictions, higher cigarette taxes, and the like) before state legislatures in 1986, only 54, or 12%, passed. In 1987, 62, or 14%, of 436 adverse bills were approved.

Tobacco has had even more success in Congress, which failed to adopt any of 160 anti-cigarette bills in 1985-86, according to the Tobacco Institute. Last year’s vote by Congress to ban smoking on airline flights of under two hours was a key setback. But so far, that is the tobacco industry’s only loss out of 99 bills before the 100th Congress.

Even though the industry still wins most of the time, it pays to have grateful allies.

Last year, when the New York City Council took up a tough indoor smoking ordinance, a coalition of minority leaders raised the specter of discrimination, arguing that clerical workers, who are disproportionately minorities, would be affected most. Opponents included members of the NAACP, the National Black Police Association and the National Coalition of 100 Black Women–all recipients of tobacco contributions.

A black magazine recently contended that blacks have a moral duty to stand up for the industry. The National Black Monitor–a monthly magazine that appears as an insert in 80 black newspapers–began a three-part series on the tobacco industry in January with a call on blacks to “’oppose any proposed legislation that often serves as a vehicle for intensified discrimination against this industry which has befriended us, often far more than any other, in our hour of greatest need.”

In the February installment of the series, the Monitor argued that racial minorities no longer face the “systematized injustice they once did. But relentless discrimination still rages unabashedly on a cross-country scope against another group of targets–the tobacco industry and 50 million private citizens who smoke.”

The author of those stirring sentiments: the tobacco industry itself. In neither issue does the tobacco-related story carry a byline. But an official of the RJR company said the firm wrote the February piece.

In 1986, leaders of the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) approved a resolution opposing workplace smoking rules that “restrict the personal freedoms of Hispanic employees in the workplace.”

The Tobacco Institute, in a memo to field staff, urged use of the resolution to rally “LULAC chapters and…Hispanic Chambers of Commerce in states and localities considering workplace smoking restrictions.” Both LULAC and the Hispanic Chambers get tobacco support.

And there was good news as well from the women’s movement, according to an institute memo in August, 1986:

“We began intensive discussions with representatives of key women’s organizations,” the memo said. “Most have assured us that, for the time being, smoking is not a priority issue for them.”

To Tell The Truth…?

To hear the cigarette makers tell it, one of the myths of American politics is that of an almighty tobacco lobby.

“I never see ‘tobacco lobby’ without the word ‘powerful’ in front,” said Brennan Moran, director of media relations for the Tobacco Institute.

Yet internal memos sometimes depict the invincible lobby whose existence the industry continually denies. Ironically, some of these memos–directed to higher-ups in the institute and the tobacco companies–exaggerate the institute’s conquests, just as the industry complains its critics do.

In a February, 1987 memo, for example, institute officials claim they “were able to influence the choice of a replacement for David Wilhelm as director of Citizens for Tax Justice”–a labor-backed policy group that opposes excise taxes on cigarettes and other goods.

But the institute played no role in picking the successor, according to Bob McIntyre, the only candidate for the job. His account was substantiated by Wilhelm and others close to the group.

“That’s ridiculous. I’m at a loss,” said Wilhelm when he heard of the institute’s boast. “That sounds like typical Washington, D.C., influence peddling…claiming credit where no credit should be claimed.”

Similarly, in an August, 1986, memo to cigarette company spokesmen, the institute claimed it had “arranged adoption of a comprehensive excise tax position paper at the first annual Hispanic Congressional Caucus Legislative Seminar.”

The reference apparently was to the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, which is made up of the 14 Hispanic members of Congress. But current and former members of the Hispanic caucus staff said the group has never adopted an excise tax paper, and has never had an annual legislative seminar.

Also in 1986, following a Senate Finance Committee hearing on proposed excise tax increases, the institute boasted of giving “staff support, including drafting testimony and press statements for National Black Caucus of State Legislators, League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAQ), Governor Baliles of Virginia, and several members of Congress.”

The former head of the National Black Caucus, Clarence Mitchell III, filed a statement with the committee, but the group’s current executive director said he did not know if the institute drafted it.

According to the hearing record, there was no testimony from either LULAC or Gov. Gerald Baliles.

Moran said she was not familiar with the memos and declined comment.

©1988 Myron Levin

Myron Levin, a reporter on leave from the Los Angeles Times, is reporting on the tobacco industry.