Not long after saying good night to the last dinner guest, the Mitchell family was dead.

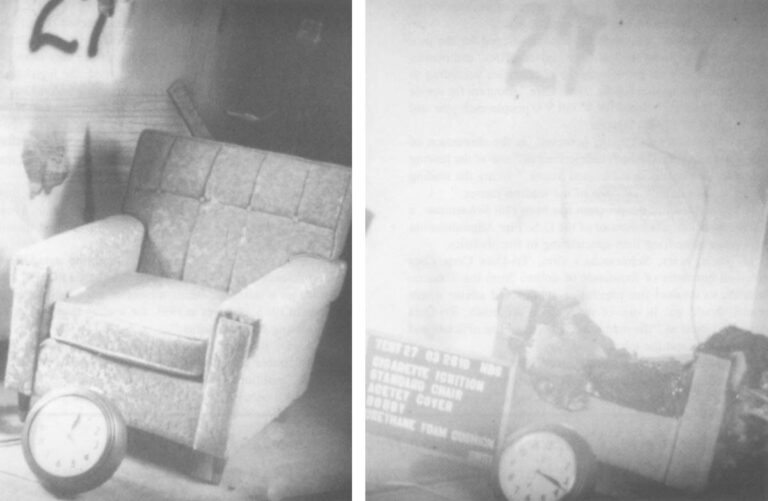

Billie Mitchell, 33, was a non-smoker-, his wife Kathi, 27, smoked occasionally. A guest may have dropped the cigarette, or maybe it spilled from an ashtray into a crack of the sofa that night in August, 1985. Apparently it smoldered, undetected, as the household slept, finally starting the fire that killed the couple, their children Jennifer, 4, and Joshua, 1, and a visiting cousin.

Bob Calvin, Billie’s friend and boss at a local trucking firm, was called next morning to the home in Taft, California, to help identify the bodies. “After the tears,” Calvin said, “I got sick.”

Calvin had been through this before. During his childhood in Oregon, Calvin recalled, two of his young cousins died, and a third was horribly disfigured by a furniture fire from a cigarette dropped at a party. “How he (the third cousin) lived is beyond everybody’s comprehension,” Calvin said.

Cigarette smoking has been called the nation’s leading preventable cause of death, accounting for more than 300,000 premature deaths a year from cancer and other diseases, according to the U.S. Surgeon General. What’s less known is that cigarettes start more fatal fires than any other ignition source, causing about 30% of all fire deaths in this country, according to government studies.

The toll from cigarette fires–about 1,500 to 2,000 deaths per year–seems paltry compared to that from smoking-related disease. But smokers presumably knew of the risk, while many victims of cigarette fires are children or innocent adults who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. Along with deaths, cigarette fires also cause at least 6,000 injuries per year and $400 million in property loss, according to a study by the National Fire Protection Association.

Cigarette manufacturers deny the frequent charge that they use additives to keep cigarettes from going out. But in the manufacturing process, tobacco moisture, paper porosity and other variables are controlled to produce cigarettes that will keep on burning when not being puffed. A cigarette dropped on a sofa or easy chair may smolder at 700 degrees © for 30 to 60 minutes, according to fire experts, which is more than enough time to ignite many types of furnishings.

The call for a fire-safe cigarette dates at least to the late 1920s, when Massachusetts Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers pushed unsuccessfully for a cigarette that would go out a few minutes after put down. In fact, dozens of patents have been issued over the years for such self-extinguishing cigarettes. The cigarette makers contend, however, that these cigarettes would have an unacceptable taste or would require use of hazardous additives.

They see cigarette fires as strictly a problem of carelessness, and not of product design. Their claim that an acceptable fire-safe cigarette cannot be produced has met with considerable skepticism, in part because tests have shown that two commercial cigarettes–Carlton and More–already are slightly safer than rival brands.

Nonetheless, the industry’s carefully guarded immunity from most health regulation extends to the arena of fire safety, where there are fire-resistance standards for many items that cigarettes burn, but none for cigarettes.

That could change after this fall, when a cigarette safety panel makes its final report to Congress. The advisory panel, set up by Congress three years ago, has found that certain physical changes–such as looser-packed tobacco–make for a cigarette that goes on burning with less chance of starting a fire. The findings are certain to renew the call for a fire-resistance standard for cigarettes.

Savvy Campaign

But the industry plans to he ready. During the last four years, it has been building a bridge–actually more of a superhighway–to the group with the most interest and influence on issues of fire safety.

In a unique and savvy lobbying campaign, the Tobacco Institute–the political arm of the cigarette firms–has lavished millions of dollars in grants and contracts on fire departments and state and national fire safety groups. The groups are to develop educational materials on fire safety and run community fire prevention programs. The campaign has been a success, according to the benchmark cited last year in an internal Tobacco Institute memo. By mid-1986, the memo said, the institute was “68 percent toward our goal of 200 working relationships within the fire community.”

This interest in fire prevention was fueled by the momentum of cigarette safety legislation. In 1979, after a family of seven in his district died in a cigarette fire, Rep. Joe Moakley (D-MA.) introduced a bill to require cigarettes to go out within five minutes of being left unattended. The following year, Moakley and Sen. Alan Cranston (D-CA.) took a different tack, introducing bills directing a federal agency to set a fire resistance standard, or to report back to Congress if it found that a fire safe cigarette was technically unfeasible.

The agency was the Consumer Product Safety Commission, which has jurisdiction over some 15,000 products. In the area of fire safety, it has fire resistance standards for children’s sleepwear, mattresses, carpeting and rugs, and applied pressure that led to a voluntary standard for upholstered furniture.

But the safety commission lacks jurisdiction over the product that is estimated to cause more injuries and deaths than any other. In 1972, when the commission was created–and then again in 1976–Congress specifically barred it from scrutinizing “tobacco or tobacco products,” even though no other agency had that authority.

Moakley complained in a speech of a “misguided policy of making the world safe for the cigarette…While hundreds of millions of dollars were being spent to make furniture, rugs and mattresses resistant to cigarettes,” he said, “nothing was being done to make the cigarette less likely to ignite.”

Tobacco executives were understandably reluctant to tinker with cigarettes, which are among the most profitable of’ all legal products. Americans spend $30 billion a year on cigarettes, or about 1 % of consumer disposable income. Naturally, the cigarette companies are wary of any change in cigarette appearance or taste that might affect sales.

Although leery of saying so publicly, the cigarette makers also are nervous about product liability claims from cigarette fires. A few lawsuits have been filed over cigarette fires, and none has been successful. But some legal experts and others believe that a sympathetic plaintiff–such as a burned child–will eventually prevail against the maker of the brand that lit the fire.

The industry would be all the more vulnerable if it were shown “that there is a technology for a fire-safe cigarette,” said a former staff member of the Tobacco Institute who would not speak for attribution. “To them, that’s a very, very scary issue.”

Andrew McGuire, a San Francisco health activist and member of the cigarette safety panel, said a lawyer for R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., the number two U.S. cigarette maker, once acknowledged the industry’s fear of liability suits.

Over lunch about five years ago, McGuire said, he was asked by the lawyer, Max Crohn: “What would be your opinion if we were to ever so slowly change the way we make our cigarettes so that they became fire-safe?”

McGuire said Crohn went on to explain:

“We are between a rock and a hard spot with products liability. If we come out with a fire-safe cigarette tomorrow, it may…show that we could have done it…If we do it gradually, then there’s a chance that it won’ be an issue.”

Crohn has a different memory of this conversation. He said he believes it was McGuire who raised the question of product liability. Crohn also said he knew of no way to make a fire-safe cigarette, and so had no basis to ask such a hypothetical question. Crohn added: “There is no way that Reynolds was not investigating the issue because of it fear that if it solved the problem it would bring about lawsuits.”

Whatever its private legal worries, the industry publicly has focused on the problem of technical feasibility, contending that a fire-safe cigarette would be unappealing to smokers or hard to mass produce. As they usually do when threatened by regulation, industry officials portray themselves as defenders of’ science against political meddling.

“Congress cannot legislate science into existence,” was a phrase heard with regularity during debate on the bills.

Industry officials further argued that a fire-safe cigarette, if one could be made, would not burn as thoroughly as current brands-and thus would deliver more tar, nicotine, and carbon monoxide in the smoke.

As there was no point in saving hundreds of people from fires so thousands more could die of disease, this seemed a potent argument. Also a novel one, coming from an industry that denies smoking causes disease. Industry officials explained that health authorities and their customers worry about nicotine and tar, even if they do not.

But after several years of’ successful resistance, the industry was forced to reassess its position. By 1984, cigarette safety bills were pending in several states, including New York, California, Massachusetts, and Illinois. Federal involvement did not seem so dreary, compared with the nightmare of different rules from state to state. So the industry cut a deal that bought it time and held the states at bay.

With tobacco industry support, Congress passed the Cigarette Safety Act of 1984–which called for a study of’ the technical and commercial feasibility of making cigarettes with “a reduced propensity to ignite upholstered furniture and mattresses.” State legislators informally agreed to put their bills on hold pending completion of’ the federal Study.

The act created a 15-member Technical Study Group–with members from government agencies, health and fire prevention groups, and the cigarette and furniture industries–to oversee a battery of technical and economic studies. The most significant research involved tests on experimental cigarettes with varying physical characteristics. The study concluded that thin cigarettes with less densely packed tobacco (those with less tobacco ‘fuel’), that were wrapped in less porous paper, were considerably more fire-safe than the best commercial brands.

Vulnerable Industry

Moreover, the study said, “some of the best performing experimental cigarettes had per puff tar, nicotine and CO2 (carbon monoxide] yields comparable to typical commercial cigarettes,” apparently knocking down a key industry argument.

In a draft of’ its final report to Congress–due October 30–the study group said “it is technically feasible and may be commercially feasible to develop cigarettes that will have a significantly reduced propensity to ignite upholstered furniture and mattresses.” An Interagency Committee–made up of top officials with the CPSC, U.S. Fire Administration, and Department of Health and Human Services–is to follow with policy recommendations by December 30.

Spokesmen for the Tobacco Institute have declined comment until of the report is final.

Dr. Richard Gann, chief’ fire scientist with the National Bureau of Standards and study group chairman, said the industry would be vulnerable to lawsuits and state legislation if it ignores the study findings.

The cigarette men on the panel “are perceptive both about their product and the prevailing climate,” Gann said. “I’m fully confident that they’ll take advantage of the technology that’s being developed by us.”

Yet the industry members contend there are practical barriers to producing the types of cigarettes that tested fire-safe. Smoking a cigarette as thin and loose-packed as the best experimental one would be like sucking a thick milk shake through a straw, Dr. Alexander Spears, executive vice president with Lorillard, Inc., manufacturer of Kent, Newport. True, Old Gold and other brands, recently told the advisory panel.

“I don’t think you could give them (the experimental cigarettes) away,” remarked Dr. Preston Leake of American Tobacco Co., which makes Pall Mall, Carlton and Lucky Strike.

In the political realm, meanwhile, the Tobacco Institute has been trying to win friends, or at least neutralize opponents in preparation for renewed debate in Congress. Fire prevention grants and contracts have been issued to individual fire officials, state and county fire agencies, and virtually every significant national group, including the National Fire Protection Association, the International Society of Fire Service Instructors. and the National Volunteer Fire Council. The grants have paid for fire prevention conferences and for development of fire safety educational materials for high school students, senior citizens and the handicapped.

More than 100 municipal fire departments, including those in the biggest U.S. cities, have also received grants, principally of audio-visual equipment and curriculum materials to run community fire prevention workshops. The Milwaukee fire department got money to buy smoke alarms for the poor, and the San Francisco fire department got a Chinese language TV spot promoting smoke detector use.

The Tobacco Institute also has developed and distributed to over 4,000 volunteer fire departments a sophisticated fundraising and membership recruitment kit, including camera-ready print ads and taped public service announcements.

The institute has further endeared itself by lobbying to preserve the U.S. Fire Administration–a perennial target of the Reagan administration budget knife. “Our efforts in cooperation with fire groups to save the U.S. Fire Administration continue to be welcomed by the fire community,” according to an internal memorandum. Meanwhile. the institute appears to have replaced the federal agency as the biggest financial supporter of fire safety education.

The investment has been “in the millions of dollars,” said institute vice president Peter Sparber. who declined to give a specific figure.

This is not “a black bag operation,” Sparber said. “We’ve tended to support almost every good fire prevention idea we’ve found, and have taken very little credit for it.”

But some of the workshop material developed for the program is reticent about the toll from cigarette fires, and blames these fires solely on carelessness. For example, according to the instructor’s manual for the “Fire Care” program for senior citizens, “cooking-related fires” kill 500 people each year and cause 8,000 to 12,000 injuries.

Such statistics are lacking, however, in the discussion of “careless smoking,” which is described as “one of the leading causes of fire deaths in the United States.” Being the leading cause, it does qualify as “one of the leading causes.”

A key architect of the program has been Phil Schaenman, a former associate administrator of the U.S. Fire Administration who has a consulting firm specializing, in fire statistics.

In recent years. Schaenman’s firm. Tri-Data Corp., has received hundreds of thousands of dollars from the Tobacco Institute to conduct fire prevention studies and advise where grants should go. In one of its contract proposals, Tri-Data described itself as “the matchmaker between fire officials and organizations and the tobacco industry.

At the same time it has served the Tobacco Institute, Tri-Data also has worked extensively for government agencies that have endorsed a fire-safe cigarette–although Tri-Data’s work for them did not directly concern that issue.

In 1985, Tri-Data had a contract with the Consumer Product Safety Commission to analyze fires involving wearing apparel. And Tri-Data currently has a $131,000 contract with Schaenman’s old employer, the U.S. Fire Administration, to investigate major fires.

Tri-Data and another tobacco industry contractor–the advertising and public relations giant, 0gilvy & Mather–have teamed up on a two year contract with the Fire Administration to boost fire safety awareness. Ogilvy & Mather got the $1.4 million contract and subcontracted $266,000 of the work to Tri-Data, according to federal officials. Ogilvy & Mather also has worked with Tri-Data on the Tobacco Institute’s fire prevention program. Ogilvy & Mather has a huge account with Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. to promote several brands, including Barclay and Capri, and has accounts with the General Foods subsidiary of Philip Morris Cos.

Schaenman said he is “extremely sensitive” to potential conflicts, but that there is none here. Officials with the Fire Administration agree. Jim Coyle, assistant administrator for fire prevention and arson control, said the agency knew of the cigarette ties before letting the contract. Coyle added: “I think we’ve gotten an excellent job out of them (0gilvy & Mather and Tri-Data) so far.”

However, one federal study by Tri-Data touched off a low-grade flap. In 1984, the firm had a contract with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to analyze fire data from 10 states. One of the states was New York, where the legislature was debating a fire-safe cigarette bill. According to Tri-Data’s analysis, arson and heating equipment fires killed more New Yorkers than cigarette fires in 1982. In a letter to state lawmakers, the Tobacco Institute promptly spread the news that cigarettes were no longer the leading cause of fire deaths in the state.

The trouble was, Tri-Data had relied on partial data that excluded New York City. Looking at the entire state, New York officials later said, cigarettes were still the undisputed leader in causing death by fire.

In a letter responding to the institute claim, the state Office of Fire Prevention and Control wrote: “As best as OFPC can determine on a statewide basis, misuse of smoking materials remained in 1982, as it was in 1981, the leading single cause of fires involving civilian deaths.”

But despite its obvious political agenda, the institute has won considerable gratitude within the fire service. Fire safety education, traditionally a neglected area, may reduce fire losses–and it certainly makes fire officials look good.

Tobacco Institute support has “been tremendous for us,” said Jim Monihan, chairman of the National Volunteer Fire Council. “We appreciate it, but we also appreciate the fact that there’s no strings attached to it.”

The institute has even won grudging praise from some of its staunchest critics. “Up front, they (the Tobacco Institute) were told you can give us money or grants, but that doesn’t stop us from going after you on the fire-safe cigarette,” said Tom Nyhan, a captain with the San Francisco Fire Department. Although the department was “close to insulting,” said Nyhan, the institute gave it a grant.

Whether this will help the cigarette makers defeat regulation–or tailor it to their needs–remains to be seen. But the program has enabled the industry to spotlight fire hazards other than cigarettes, while rehabilitating its image with an influential group.

“Between you and me, five years ago, I wouldn’t even sit in the same room with people from the Tobacco Institute,” said a former official of a leading fire safety group.

Said the institute’s Pete Sparber: “Doing reasonable things with reasonable people is good politics…We are acting in good faith. If that counts for anything…we should benefit.”

©1987 Myron Levin

Myron Levin, a reporter on leave from the Los Angeles Times, is reporting on the tobacco industry.