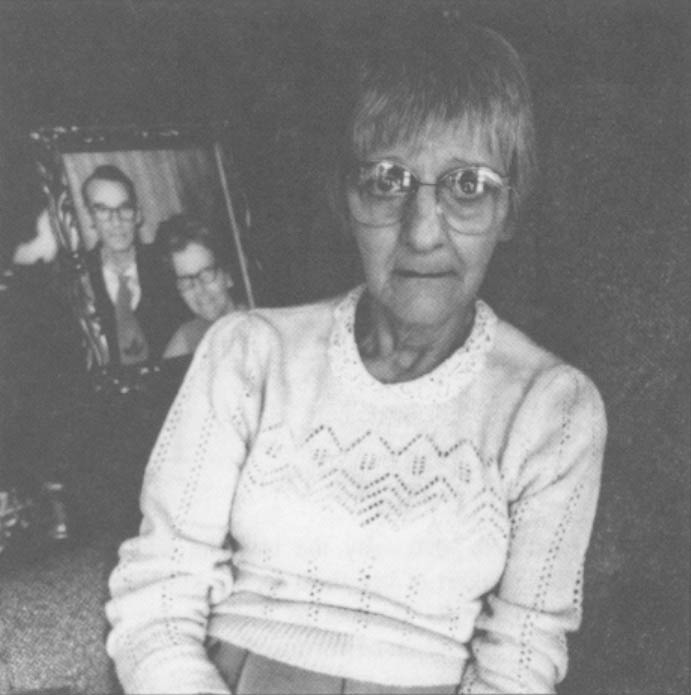

WEST GROTON, MA.-By the time he was 40, Milton Wheeler was too short of breath to fix the kids’ mini-bikes or play a round of golf. He had to give up his career as a policeman–and his dream of becoming chief–there being no place for a small town cop who couldn’t haul a stretcher.

Wheeler spent his last months tethered to an oxygen tank, taking an hour and a half to totter to the bathroom and back to his hospital bed.

“He stared at the bathroom, thinking about how he was going to get in there, and wouldn’t let anyone help him get in there, and that’s how he lived his life,” his oldest son Garry recalled.

In 1982, just after his 50th birthday, Milton Wheeler died of asbestosis, a disease caused by scarring of the lungs by asbestos fibers. Asbestosis was a word he’d never heard until the doctors said he had it. In a fleeting, nearly forgotten chapter of his life, Wheeler worked with asbestos at a paper mill for a few months in 1953-54. His exposure must have been very heavy, for asbestosis usually signifies years of asbestos exposure. Like many others at the mill who were killed by asbestos, Milton Wheeler wasn’t told it was dangerous.

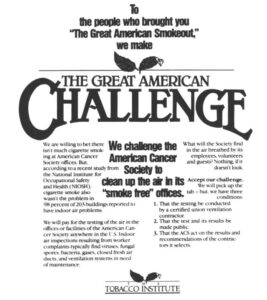

In those days, the talk was of a hazard of a different sort. By the early 1950s, the link between smoking and lung cancer–long discussed in medical journals–was getting increased attention in the popular press. As they do to this day, the tobacco companies denied smoking was dangerous, but behaved as if they knew better. Threatened with the loss of jittery customers, they launched new filter brands to convince smokers their habit could be safe.

Despite audacious health claims, studies showed some of the early filters trapped tar and nicotine no more effectively than unburned tobacco. Regardless, the filter revolution saved the cigarette makers, propelling them to record sales and profits. Once an oddity, the filter tip soon dominated cigarette sales, as millions who might have quit were able to rationalize their habit, thanks to these “safer” smokes.

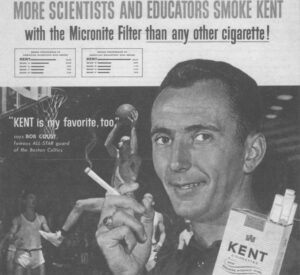

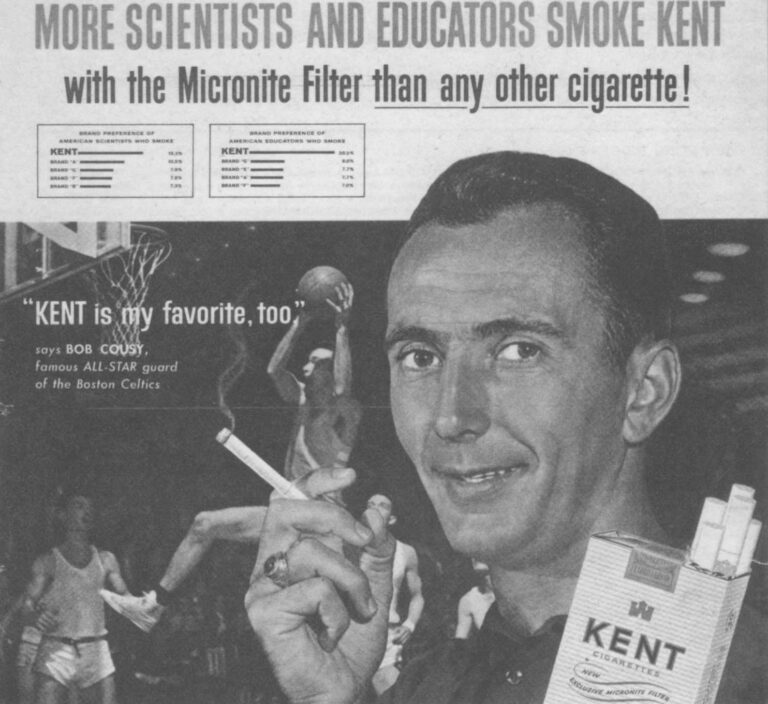

Smokers bought L&M filters, said to be “just what the doctor ordered!” They bought Parliaments, which provided “maximum health protection.” And they bought Kent, whose “Micronite” filter made the biggest splash of all.

Kent was launched in 1952 by P. Lorillard Co. and named for its president, Herbert A. Kent. Something of a maverick among the cigarette makers, Lorillard came closest to admitting that cigarettes were harmful. It promoted Kent as the brand for “the 1 out of every 3 smokers who is unusually sensitive to tobacco tars and nicotine.” It said Kent offered them “the greatest health protection in cigarette history.”

In double page magazine ads that played on the public’s gee-whiz faith in science and technology, Lorillard said its quest for the new filter “ended in an atomic energy plant, where the makers of KENT found a material being used to filter air of microscopic impurities.”

“What is ‘Micronite’?” another ad asked. “It’s a pure, dust-free, completely harmless material that is so safe, so effective, it actually is used to help filter the air in hospital operating rooms.”

In reality, the Micronite filter–whose actual composition the ads never revealed–contained a particularly dangerous form of asbestos. It was dust from this “dust-free, completely harmless material” that killed Milton Wheeler and more than a score of others who made filter material for Lorillard.

There was asbestos in the filter from 1952 at least until 1957. During this time, according to sales figures, Americans puffed their way through over 13 billion Kents. It is unknown if Kent smokers inhaled asbestos from the filter, or if they have experienced a higher rate of cancer than smokers of other brands.

Lorillard would not respond to written questions on this subject, nor to separate requests to three vice presidents to tell the company’s side. The company offered a single piece of information:

“We do not have asbestos in our products, nor have we had for many years,” said Sara Ridgway, Lorillard vice president for public relations. “That is all I’m going to say.”

Lorillard bought the asbestos material from a subsidiary of Hollingsworth & Vose Co., a Massachusetts-based manufacturer of paper and filter products. The subsidiary, H&V Specialties Co., Inc., which employed Milton Wheeler, was created specifically to supply Lorillard from plants in West Groton and Rochdale, near Boston.

According to correspondence between the firms, rolls of the asbestos material were shipped to Lorillard factories in Jersey City, N.J., and Louisville, Ky. This correspondence–produced in connection with lawsuits on behalf of dead or ill Specialties workers–shows that the Micronite filter was a blend of 30% asbestos and 70% cotton and acetate. The type of’ asbestos was crocidolite–also known as African or Bolivian blue for its origin and distinctive color. Crocidolite is regarded by many experts as the most hazardous of the six asbestos minerals.

Lorillard still uses the Micronite trademark. But for reasons it won’t explain, Lorillard quietly stopped doing business with Specialties, which went out of business in 1957.

In August of that year, an article in Reader’s Digest mentioned the asbestos content of the Kent filter, but said Lorillard had just developed a new recipe. Because the hazards of asbestos then were unknown to readers-and apparently to The Digest staff–what might have been a sensational disclosure instead proved a forgettable detail. In fact, Kent sales boomed because of the article, which praised the Micronite filter as more effective than rival brands.

Lorillard itself noted–but did not explain–the filter’s redesign in “Lorillard and Tobacco,” a company history every bit as self-serving as the ads for Lorillard’s brands. According to the booklet:

“an intensive research program was ordered to make the Kent Micronite filter even better. The directive emphasized the objective of a more flavorful smoke within a filter cigarette. Lorillard scientists developed and sent countless experimental filter cigarettes to headquarters over a period of many months. Each was tested and tried–until February, 1957 when at last word went to the laboratory ‘You’ve done it!’…The Kent filter, revolutionary when it first appeared in 1952 and brilliantly improved in 1957, showed how scientific innovations anticipated, and kept pace with, consumer demand.”

Lorillard may have changed the filter to cut costs, since the original version was expensive and Kent was handicapped by its premium price. The original filter also was too dense to suit most smokers, who had to draw extra hard to get any taste.

“They were a witch…to inhale,” said Dorothy Peters, whose husband Sidney’ a Specialties worker, died of asbestosis and lung cancer at the age of 51. “You had to pull your guts out to smoke the damn things.”

Given the dangers of smoking, the question of asbestos inhalation by Kent smokers may seem beside the point. But studies have shown that people breathing asbestos and cigarette smoke run a much greater risk of lung cancer than those exposed to one of these hazards alone. The risks are not additive but multiplicative.

Whatever the effect on Kent smokers, the impact on Specialties workers was devastating. Despite the high-tech hype of the Kent ads, the Micronite filter was made under fairly primitive conditions.

Few Precautions

Rather than being handled wet, which would have reduced the dust, the asbestos was processed dry with textile equipment. Workers slit open bags of raw asbestos, piled it by hand on a conveyor with the cotton and acetate, and ran it through a “picker”–a rotating cylinder festooned with spikes that ground the mix to bits.

Dorothy Peters recalled seeing clumps of the dust “hanging from the rafters” at the West Groton plant when she brought her husband’s lunch. One employee at the Rochdale plant remembered a co-worker whose “very long eyelashes…would have a bluish tint to them from the dust.”

At the end of the day, the men used an air hose to blow dust from their clothes and hair, flinging the settled fibers back into the air. At least some workers were furnished protective masks, although these apparently were of limited value.

According to Milton Wheeler, in a deposition before his death, the picker raised a bluish dust so thick “you couldn’t see from one end of the machine to the other.” According to Wheeler, at the end of a shift:

“You looked like a huge teddy bear. You were covered from the top of your head to the bottom of your toes. You were covered with dust and the fibers of all three components, the acetate, the cotton and the asbestos. It would be in your ears, it would be in your nose, even through the mask. It would be under your pant legs, it would be inside your socks. You’d just be literally covered with it. You’d be blue.”

It was a “dust creating monster,” said Dr. James Talcott, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, where some of the dying have been treated. “There couldn’t have been a better means of trying to produce respirable asbestos fibers,” Talcott said. “There’s nobody who worked in the Micronite filter project…who wasn’t extremely heavily exposed.”

Dying From Work

This reporter has reviewed death certificates or hospital records of more than 20 Specialties workers who died of asbestosis, lung cancer, or mesothelioma, an extremely rare and virulent form of cancer almost invariably caused by asbestos inhalation.

This is hardly a thorough count, as is evident from an ongoing study by Talcott and a team of researchers in Boston. They have traced 36 men who worked for Specialties in 1953. Seven are still living, some of them suffering from asbestosis. Of the 29 who are deceased, more than half died of asbestos-related disease, said Talcott, who stressed the numbers are preliminary.

If similar proportions hold for the roughly 160 men who worked for Specialties during its five year life, several dozen workers have died of asbestos -related disease.

West Groton, about 50 miles northwest of Boston, is a mix of millhands and white-collar commuters, a quiet village set among orchards and lush green fields and pine-shaded country roads.

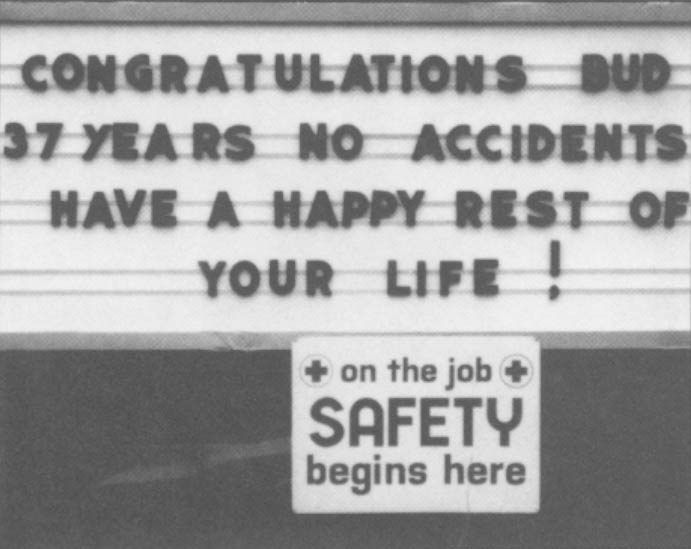

In front of the Hollingsworth & Vose mill on the Squannacook River is a sign that proclaims: “The Right Time For Safety Is All The Time.”

With a payroll of 180, the mill has always been among the biggest employers around, a source of steady work and plenty of it, where men work double shifts for the overtime pay.

It is a family mill, with a tradition of fathers and sons and kid brothers working–and sometimes dying–together. Elizabeth Jacobs’ 40-year old brother Raymond McDowell, died of asbestosis and pneumonia in 1970. Her husband, Joe Jacobs, 61, died of mesothelioma in 1982. Both men worked for Specialties.

In 1985, Elizabeth Jacobs herself died of mesothelioma at the age of 54. Her only known asbestos exposure came from washing her husband’s clothes.

For some men, cigarettes were at both ends of the problem, because smoking aggravated or contributed to their asbestos disease. At times, they helped themselves to free packs of Kents, sent by the case from a Lorillard factory as a gesture of goodwill.

For each one who, like Milton Wheeler, died slowly year by year, there was another who went with stunning swiftness.

Friends remember Dick Valcourt as a powerhouse, a man who could lift a 150 pound motor by the shaft as if it were a six-pack of beer. Valcourt worked for Specialties in West Groton and continued at the Hollingsworth & Vose mill after the Micronite project shut down. Clearly quite ill last winter, he continued showing up for work until supervisors yanked his time card to make him see a doctor.

A friend who saw Valcourt in the hospital a few weeks later was shocked at his wasted appearance. “His arms were no bigger than that,” said George Griffin, curving his hands to form a small ring. “I couldn’t believe it. It made me sick.” In May, the 57-year old Valcourt died of mesothelioma.

There’s been an element of universality to this suffering and death. One of the first to become ill was Lorrel Nichols, general manager of Specialties, who died of asbestosis and lung cancer in 1964. Three years later, Anthony O’Malley, a foreman in both West Groton and Rochdale, died of lung cancer at age 55.

Tom Obea was a Specialties worker later promoted to personnel manager of the West Groton mill. In 1974, he died of asbestosis and mesothelioma at the age of 48.

Some victims worked for Specialties so briefly that when diagnosed years later, they had to be pressed by doctors to recall where they’d encountered asbestos.

While in his 20s, Bernard White worked briefly at the Rochdale plant, and then served for years as a policeman, later as a manager of public skating rinks, and as a selectman in his home town of Oxford, Massachusetts. Last February, White died of mesothelioma at the age of 56.

His son Bruce White, said recently: “You talk about people that smoke for 30 years and contract cancer and die from it, or they work 30 years in some place and contract cancer and die from it…

“But when you just work there a year and a half and then 30 years later you contract this disease and die from it, it’s worse, to me. You know, it’s almost like that little piece of [his] life shouldn’t even have been there,” Bruce White said.

“What it really boils down to is he could have worked there just a couple of days and contracted this.”

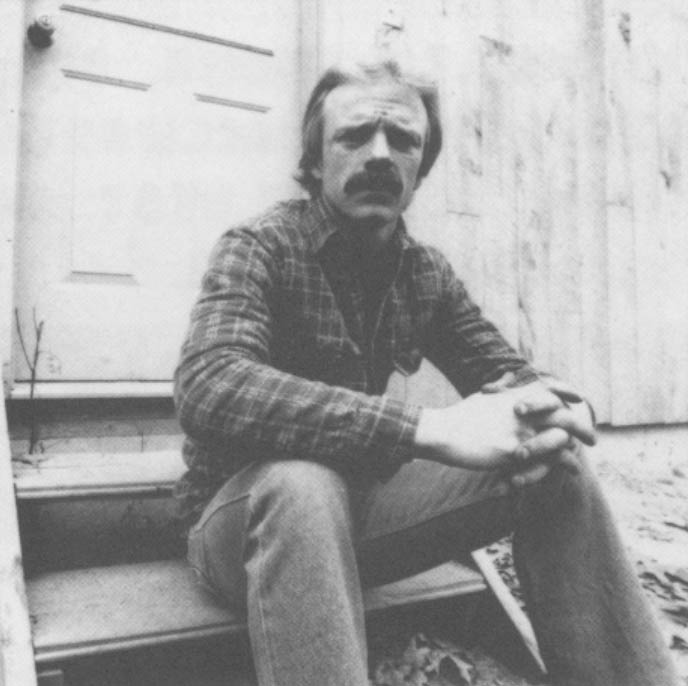

Love and heartbreak twist the face of Phil Lemere, Jr., when he recalls his father’s death a year ago from mesothelioma. Phil Sr. worked a few months for Specialties between high school graduation and the Army. He went on to earn a masters degree in education, teach junior high school, and start a small business.

Phil Jr. remembers his father’s uncommon honesty and “wicked dry sense of humor.” He was best man at Phil Jr.’s wedding, and the two were side by side on the morning he died.

“The fluid was building up. He was as big as a whale. His arms were like this big around, filled up with fluid, and I stayed with him all night,” Phil Jr. said.

“I woke up hearing him gurgling and stuff and, you know, I just leaned over him, just talking to him and I said, ‘Dad, you know, it’s okay. We all love you. It’s just time to go’ I told him, ‘Ill be with you again some day’…

“He just knew it was time to let go and he just stopped breathing. He just stopped breathing.” He was 51 years old.

The dangers of asbestos were not widely publicized until around 1970. Before 1950, however, articles in various medical journals had linked asbestos exposure to asbestosis and lung cancer. In Massachusetts, the first workmen’s compensation claim by an asbestosis victim reportedly was upheld in 1927.

Hollingsworth & Vose had worked with asbestos since the 1940s, when it helped the U.S. military develop an asbestos filter paper for use in gas masks. But company officials have said they did not realize the danger to workers on the Micronite project. In a deposition last year, Dr. Harold W. Knudson, the former Hollingsworth & Vose vice president and research director who held patents on the cigarette filter, said he had been “only vaguely” familiar with the term asbestosis.

Aubrey K. Nicholson, former president of Hollingsworth & Vose, denied that the company supplied masks because it knew asbestos was dangerous. In a deposition, Nicholson said the masks only were meant “to prevent the unpleasantness, and inconvenience, and lack of comfort from dust.”

Andrew McElaney, a lawyer for Hollingsworth & Vose, pointed out that Specialties made various safety improvements suggested by state health inspectors, who did not seem unduly alarmed by conditions at the West Groton plant. “Here we had a small Massachusetts company being told by these experts that the situation was safe,” McElaney said.

He described Hollingsworth & Vose as “a very concerned employer” that did not “knowingly subject any employee to substantial risk of harm.”

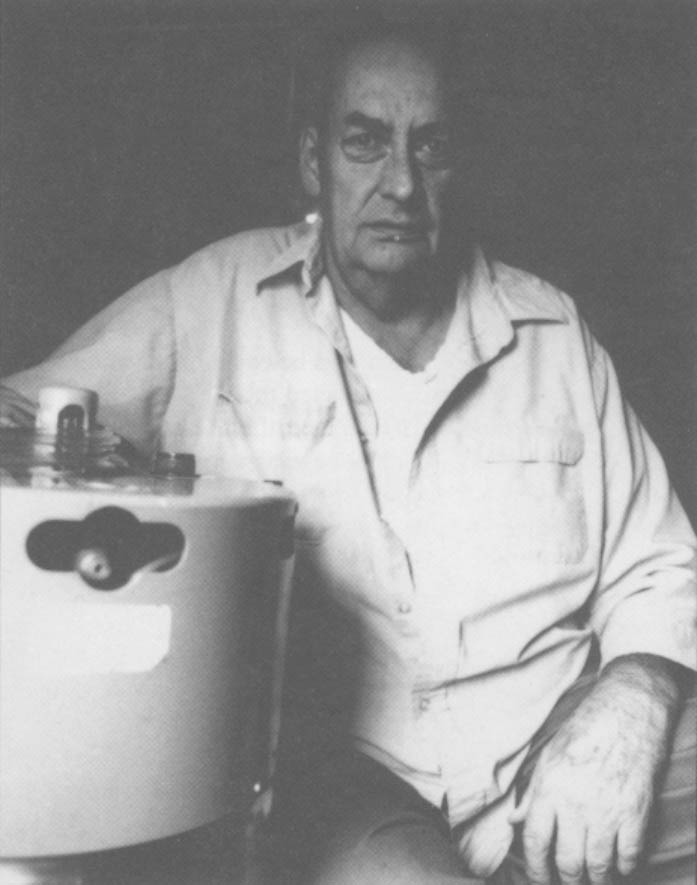

Some disagree. “I think they realized what asbestos was,” said Jake Nutting, 55, a former Specialties worker now disabled by asbestosis.

“I mean, if I was in business or you was in business, I’m sure you would know or try to find out what the consequences arc of what you were doing,” Nutting said. “There was some educated people there.”

Others give the company the benefit of the doubt. “I think at that time, the company was just as ignorant as we were,” said John LaValley, 47, who works at the West Groton mill and whose father, Francis LaValley, an ex-Specialties worker, died in 1980 of lung cancer and asbestosis.

Said Francis Silvia, 72, a former Specialties worker who is in good health: “I think that at the beginning that they probably didn’t know what it was all about, because they had foremen that died, too.”

Then again, Silvia said, “I don’t think they worried too much…They could always get plenty more help.”

Several lawsuits have been filed against Hollingsworth & Vose by stricken former workers or their families. Workmen’s compensation laws bar suits against employers, but at the time the men worked for the Specialties subsidiary, not Hollingsworth & Vose itself.

At least four of the suits have been settled out of court. Last year, Milton Wheeler’s family got a settlement worth “seven figures,” according to its lawyer Albert Zabin, who said he was barred by the agreement from stating the exact amount. Survivors of cancer victim Lewis Johnson also settled, said their lawyer, “for an amount of money that the client was happy to receive.” Suits by the Lemere and Jacobs families also were settled this fall. McElaney would not comment on any of the settlements.

Apparently none of the suits has named Lorillard as a codefendant, nor has Hollingsworth & Vose filed cross-claims asking that Lorillard share in any damage awards. Neither is Lorillard contributing to Hollingsworth & Vose’s legal defense, according to McElaney.

Whatever Hollingsworth & Vose knew about the hazards of asbestos, it seems likely that Lorillard knew less. The cigarette company was looking for a good filter, and heard of Hollingsworth & Vose’s work for the government.

Already facing a lung cancer scare, it’s hard to imagine Lorillard understood the implication of using asbestos.

On the other hand, Lorillard’s failure to identify the ingredients of the filter it so heavily promoted seems odd, especially given its breathtaking description of Micronite as a pure, dust-free, completely harmless material.”

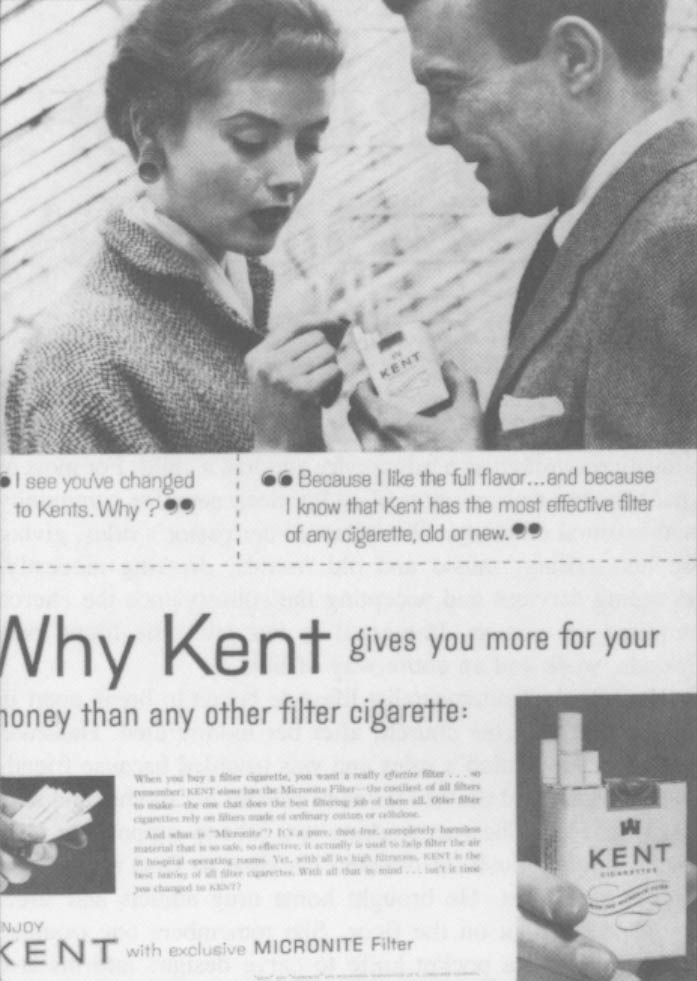

About the same time this crept into Kent’s ad copy, Liggett & Myers was touting the “strictly non-mineral” filter of its L&M brand.

Liggett & Myers seems to have been kicking Lorillard under the table. The companies must have been talking to each other. because “dust-free” and “non-mineral” were hardly effective come-ons to smokers.

“Dust-free” was surely a strange claim to make in a cigarette ad. It seems less intended to push people toward the cigarette counters then to head off future controversy.

About the Companies

Lorillard, Inc. (formerly P. Lorillard Co.). is the country’s 4th-largest cigarette maker, producing such brands as Newport, Kent, True, and Old Gold, as well as small cigars and chewing tobacco. In 1986, Lorillard had sales of nearly $1.6 billion, excluding taxes, turning out over 47 billion cigarettes for an 8.1 percent share of the U.S. market.

Lorillard is a subsidiary of Loews Corp., which also has hotel, insurance, and watch manufacturing interests, and a controlling, 25% stake in CBS, Inc.

Hollingsworth & Vose, based in East Walpole, Mass., is a privately held manufacturer of specialty paper and filter materials, with annual sales of more than $100 million, according to Paper Age magazine.

The company has plants in Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, Mexico and England. Over the years, Hollingsworth & Vose’s product line has included gasket materials, and fiberglass and asbestos media for use in gas masks and oil and air filters.

©1987 Myron Levin

Myron Levin, a reporter on leave from The Los Angeles Times, is reporting on the tobacco industry.