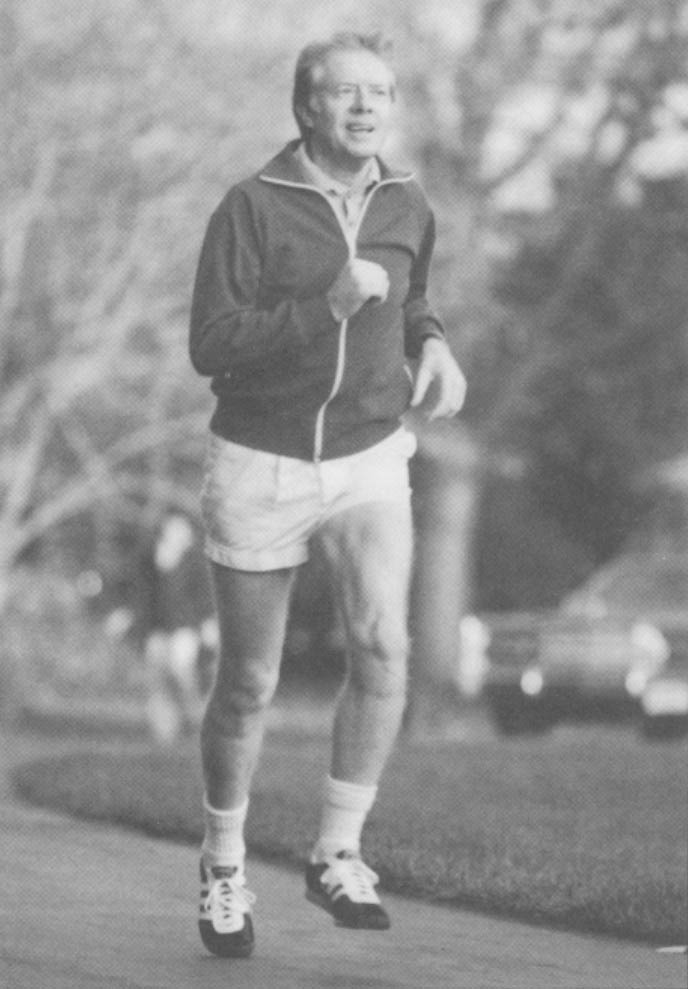

ATLANTA–Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter may be getting older but a computer recently told them they are far younger than their actual ages.

They are among the first to undergo a new computerized health risk appraisal developed here at the Carter Center of Emory University in collaboration with the federal Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and 20 other public and private health groups. The sophisticated quiz is an innovative effort to tie personal health habits to the latest scientific evidence of a person’s chances of dying.

The computer concluded that the former President, who is 63, and First Lady, now 60, are in a sense no older than when they left the White House. His health “risk age” is only 56: hers is 52.

Their good health is credited, in part, to the way they live. They don’t smoke, stay trim, jog regularly, watch what they eat, drink in moderation. and always try to use their seat belts.

“They are both in disgustingly good health,” said Carrie Harmon, the Carter Center’s young spokeswoman, with a hint of envy in her voice.

“It’s reassuring to know, we are doing O.K.,” said Jimmy Carter. “I thought that it was very nice to be 52 again,” laughed Mrs. Carter.

The Carter Center’s health risk appraisal, which is called “Healthier People”, looks at an individual’s past and present health status, as compared to a comprehensive database of disease and death statistics. The goal is to inform individuals about actions they can take to raise the odds of living longer and healthier lives.

The computer found little the Carters could improve upon (she was urged to work on her cholesterol level), in part because they have been working steadily on their health since undergoing an earlier version of risk appraisal a few years ago. They had gone from lackadaisical seat belt use to “always” and worked on their diets, so that both met the computer’s perfect weight recommendations this time around.

In contrast, a 25-year-old man who speeds, drinks while driving, fails to use seat belts, and smokes might be warned that he is already more than 30 in “risk age” and his current risk of dying in the next 10 years is more than twice the average for men his age. He would be given advice for reducing his risk to that of a 19-year-old.

“The potential is almost unlimited for improving health at a very low cost,” former President Carter said in an interview. He’s eager to see health risk appraisal used routinely–from patients entering hospitals to college students, military personnel and other employees. “For the first time in history, we have the knowledge to be in control of our own health,” added Mrs. Carter.

Others caution that wider use of the health risk appraisal must be accompanied by safeguards to assure that it is used voluntarily and confidentially. And there is debate about whether health risk appraisal should be used as a financial carrot–or stick–in providing insurance or employment.

It is not yet known just how effective the appraisals are in motivating people to change the way they live.

The nation’s leading public health authorities have long been preaching that better habits–smoking cessation, changes in diet, exercise, safe driving–could have a dramatic impact in preventing premature deaths. Despite growing concern about the hazards of pollutants in the workplace and in the world around us, health experts agree that the biggest killers in the United States are largely still under individual control.

Each year more than two million Americans die, two-thirds of them from three chronic diseases: heart disease (about 770,000 deaths), cancer (about 460,000 deaths), and stroke (about 150,000 deaths). Accidents take nearly 100,000 lives annually, about half of them from motor vehicle crashes, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

A major study done for the Carter Center estimated that about two out of three deaths and one out of three hospitalizations in the United States are linked to a few key risk factors or precursors that are potentially preventable causes of illness and premature death.

The study, called “Closing the Gap” because it focused on what could be done with existing knowledge, singled out six main personal health risks: tobacco, alcohol, injury risks, high blood pressure, over-nutrition (as measured by obesity and high cholesterol), and gaps in primary health care, particularly in prenatal and reproductive health services.

These risk factors also account for 70 percent of “potential years of life lost,” a numerical measure of the killers that most affect younger Americans and rob them of the productive years before age 65, the Carter project found. While tobacco is the leading risk factor, accounting for nearly one in five deaths, injuries are the leading killer of the young.

“The precursors identified were nearly all within the personal control of most Americans,” said CDC researcher Dr. Robert Amler in a recent special issue of the American Journal of Preventive Medicine. Amler headed the “Closing the Gap” project as well as development of the Carter Center/CDC health risk appraisal.

Although the Carter Center method is state-of-the-art, health risk appraisal is not new. A survey last year by the Department of Health and Human Service’s Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion found 50 different health risk appraisals for sale at prices ranging from a few dollars to $40 each.

Perhaps 5 to 10 million Americans have had at least one health risk appraisal, estimates CDC health risk appraisal expert David Moriarty.

The origins date to the late 1940’s when large-scale studies of the causes of heart disease and other chronic diseases began. In the 1960’s, researchers sought to apply the emerging data toward development of a practical tool for health care professionals.

In 1970, an Indianapolis physician, Dr. Lewis Robbins, and his colleague Dr. Jack Hall, wrote a book called “How to Practice Prospective Medicine” that laid out a method for calculating an individual patient’s total risks. It used probability tables showing the average risk of dying from known causes over a 10-year period for large groups of people of the same age, sex and race. This was then compared to predictions of how certain behaviors or conditions affect these average risks. The data came from government tables based on death certificates and census information.

Initial health hazard appraisals were hand-calculated, but government health officials soon became interested in the potential use of computerized health risk appraisals. In the late 1970s, CDC offered for public distribution a health risk appraisal adapted from software earlier developed by the Canadian government. A competitive industry of private vendors also sprang up.

Health risk appraisal has not yet become widely used in physician’s offices, in part because there is no strong financial incentive, says Robbins. But it has been used widely in the workplace. A new survey for the government’s Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion found that about 7 percent of private employers with 50 or more employees have used it.

It has been promoted as a voluntary and confidential means of providing health information to employees. At the same time, the health data can be anonymously incorporated into group reports that provide guidance in planning company health promotion programs intended to reduce health costs.

But widespread acceptance in the medical and scientific community has been impeded by concerns that past appraisals varied widely in quality, accuracy and impact.

“The power of this instrument has been underestimated,” says Dr. D.W. Edington of the University of Michigan, whose center has administered over 200,000 health risk appraisals. In a recent study in the American Journal of Public Health, he found that the old CDC appraisal proved “very good in predicting mortality” when compared to the actual experience of a large community health study in Tecumseh, Michigan.

A recent review by Victor Schoenbach and colleagues at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, scheduled for publication in Health Services Research, cautiously found that health risk appraisal “may be a useful tool for health education” but “no study published to date provides a real test of (its) effects on health-related behavior change.”

A five-year unpublished study, conducted for the Kellogg Foundation on 1,700 patients in Tucson, Ariz., did find measurable benefits–less smoking, weight loss, cholesterol reduction, improved health knowledge–among those who received health risk appraisal with or without educational follow-up. The changes appeared more long-lasting in those who received behavior-change courses targeted to the health problems uncovered in the appraisal.

“We found that mortality information has a bigger impact on people over 40. People under 40 want to feel good. People over 40 are starting to be real concerned,” said Sabina Dunton, president of Well Aware about Health, a Tucson health promotion company that did the study. “Health risk appraisal seems to motivate, heighten awareness, give people the feeling that they have control and are not fatalists. But it is not sustained unless they become actively involved in changing their lives.”

Dr. Marshall Becker, head of the department of health behavior at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, concluded that existing health risk appraisals “seem most appropriate to white, middle-class, middle-aged clients.” The health jargon and statistical feedback may be difficult for the less-educated to understand, he said. And the pressing day-to-day economic needs of the poor may make it less relevant and more difficult to change lifestyle and health habits.

Some critics also have expressed concern that health risk appraisal and health promotion programs may blame the victim and divert attention from more controversial environmental, occupational or social problems. “In the politics of the workplace, this may be perceived as a dodge by the employer from tackling the real problems in the workplace,” said Dr. Alexander Cohen of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

Nonetheless, given the overall promise of health risk appraisal, in 1985 the Carter Center, with CDC help, decided to launch a major national effort to develop a more scientifically credible, standardized instrument. “We wanted a gold standard for the industry,” said the center’s director, Dr. William Foege, a respected former CDC chief who earlier helped lead the global effort to wipe out smallpox.

Advisory panels of top scientists, including those from the well-known Framingham, Mass. heart study and from the National Cancer Institute, scrutinized the available scientific data for making risk assessments and computer experts sought to produce a flexible program that could be easily updated as new information came along. It was field-tested at 28 sites in 15 states on about 2,000 people, said the Carter Center’s Martha Alexander.

The initial results were unveiled to health professionals at the September meeting of the Society for Prospective Medicine, the small professional group that has nurtured health risk appraisal’s growth, and in October at the American Public Health Association meeting.

The Carter Center approach won the endorsement of two former assistant secretaries of health, Dr. Julius Richmond, who served in the Carter administration, and Dr. Edward Brandt Jr., a Reagan appointee. “It’s a very important development,” said Richmond.

Health risk appraisal pioneer Robbins, now in his late 70’s, called it “the best method available to tell an individual what his actual health needs are…It is a tremendous step forward. Before we didn’t have one package that would say, ‘this is the best we can do.’ “

While the Carter health risk appraisal is aimed at all adult Americans, the new director of the project, Dr. Edwin Hutchins, hopes that new versions can eventually can be customized to meet the special needs of the young (who may not respond as well to mortality predictions and may be motivated by more immediate disease and disability prospects), high-risk occupational groups, as well as different ethnic and economic populations.

Dr. Thomas Welty of the Indian Health Service has already used an earlier version of health risk appraisal on a South Dakota tribe of Sioux Indians and is now working with the Carter Center to adapt the new version for Indian use.

Hutchins is also working with the Army on a military version and the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association on rural distribution. And NIOSH is developing a special pilot version for firefighters, to take into account their high occupational risks.

Insurance companies are also showing strong interest in health risk appraisal. The Prudential Insurance Company, whose foundation has pledged $500,000 to the Carter Center project, recently developed its own voluntary program to offer health risk appraisals to all Prudential employees starting next year. Earlier it pilot-tested a more basic lifestyle quiz that resulted in 20 to 25 percent group premium discounts for employers with healthier employees, said Dr. Dan Dragalin, a Prudential vice-president. “I really think that you will see insurance rating done on health risk appraisal in the future, both on group rates and on individual rates.”

A model state regulation recently passed by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners would require insurers offering certified wellness plans to give discounts based on healthy habits.

“The idea is an intriguing one,” said Dona De Sanctis of the Health Insurance Association of America. “We prefer to encourage employers to develop voluntary wellness programs, rather than mandating formalized discounts.”

Despite the good intentions of many health risk appraisal advocates. Nancy Gertz, a health policy doctoral student at Boston University and former head of health promotion at Equitable Life Assurance Company, is concerned about potential adverse consequences if health risk appraisal becomes a tool directed at unhealthy individuals for insurance or employment purposes.

“If health risk appraisal were to be used for discriminatory or barrier purposes for people at higher risk, it would mean a disproportionate burden for poor, minorities or the generally disadvantaged,” she said.

“It is the same problem as with any other medical information. This is personal information that is no one’s business except the worker’s,” said Sheldon Samuels, administrator of the union-backed Workplace Health Fund. His group is developing its own health risk questionnaire, which asks lifestyle, environmental and occupational questions and provides a descriptive, not numerical, warning about possible risks. It is expected to be tested soon on shipyard workers in Norfolk, Va.

Samuels also worries about the prospect of discrimination in the workplace, but emphasizes that “the key is the ethical backbone of the corporate physician.”

Health risk appraisal can run into fierce opposition if workers view it as too intrusive into their personal lives. An attempt by Seattle City Light, a public utility, to use an elaborate 17-page questionnaire was thwarted last August by a lawsuit that contended it violated privacy rights under the Washington state constitution.

Richard D. Eadie, a lawyer who represented two employees and a local union, argued that the questionnaire went into very personal areas that “could lay the foundation for random drug testing.” He said, “In our view, individuals could be identified” and could be subjected to reprisals.

Employees were asked, he said, their opinions about management as well as whether they picked up hitchhikers, carried a gun, lived or worked at night in a high-crime area or sought or used drugs or medication that affected their moods or helped them to relax.

If it had focused only on “legitimate health questions,” said Eadie, “I don’t think we would have had a problem. My clients are very much in favor of wellness programs.”

A City Light spokesman, Hugh McIntosh, said the questionnaire’s purpose was misunderstood, perhaps because it was prepared and sent out without enough employee participation. He said that no new surveys are in the works but the utility would go ahead with some kind of wellness program.

“There is potential for abuse,” acknowledged the Carter Center’s Foege, emphasizing that “this should be an instrument to help people, not hurt them.”

For some, the help may be too late; for others, just in time. Rob Ryder, a Colorado health promotion expert, recalled a horror story about an overweight smoker in his early 50s who received a health risk appraisal report and responded, “According to this, I should have been dead two years ago.” Two days later, he died from a heart attack. “He was the classic case. When he died, it brought home the reality” for other employees, Ryder said.

Don Schewe, director of the Jimmy Carter library, says health risk appraisal saved his life. He took an earlier version and “what jumped out at me was that statistically I could improve my chances of living longer by buckling my seat belt.” He began to use a seat belt frequently and soon afterward tested his luck. He was rear-ended driving to work and although his car was destroyed, he walked away.

“I have never not buckled my seat belt since then,” added Schewe, who had a similar but more serious accident last summer that might have killed him but for his seat belt. Afterward, he called the director of the Carter health risk appraisal project and said, “Hey, I’m convinced.”

“This is a powerful tool to explain this is a cause-and-effect world,” says the Carter Center’s Foege. “We can predict, within limits, what can happen to people based on their habits. This isn’t a dress rehearsal. Our lives are the real thing. We can use health risk appraisal to make the most of the lives we do have.”

Taking The Test: Honesty Counts.

Taking a health risk appraisal can be satisfying or sobering, depending on how healthy-and how honest you are. A person who takes the new computerized Carter Center risk appraisal fills out a four-page questionnaire and the computer sends back a two-page report card.

The printed questionnaire emphasizes that this “is an educational tool” not a fortune teller. “It shows you choices you can make to keep good health and avoid the most common causes of death for a person your age and sex. This health risk appraisal is not a substitute for a check-up or physical exam.”

The 45-question quiz, suitable for adults 18 years and over, includes physical characteristics like height, weight, blood pressure and cholesterol as well as an array of lifestyle questions about smoking, driving, drinking, and health care habits. Women are asked questions about breast exams and pap smears and women and men about how long it has been since they got a rectal exam.

The answers are fed into a program that can be run on a personal computer. It then prepares a personal health report comparing a person’s current age with a computed “risk age” and a target age that is theoretically attainable with a bit of behavior change.

The most common causes of death for people of the same age and sex are compared against the participant’s own odds, listing risks that can be changed. For those who need a morale boost, the printout also singles out a person’s “good habits” (almost everyone is bound to have some) and a breakdown of “risk years” that can be gained.

The Carter Center’s Dr. Edwin Hutchins constructed some hypothetical examples to illustrate the bad and good ends of the habit scale:

Consider a 55-year-old man who gets the bad news that his “risk age” is 69.5 years and he is at high risk of dying of a heart attack in the next 10 years (his risk is over 50 percent, compared to an average of 5 percent for men his age). The good news is that he could gain nearly 16 years–a target age of 53–by treating his cholesterol (6 years), quitting smoking (4.8 years), lowering his blood pressure (3 years) and other changes. This man has no good habits.

In contrast, a fit 55-year-old nonsmoker with no health problems might learn that his “risk age” is 46.3 years, right on target. His challenge is to keep up the good work.

A high-risk 25-year-old woman might be shocked to learn that her risk age is comparable to that of a 55-year-old woman. She could theoretically cut her risk back 30 years if she reduces her high cholesterol (minus 15 years), quits smoking (6 years), lowers her blood pressure (5 years), and other changes. Her risk of dying over the next decade is about 5 times higher than the average for women her age.

Not all risks can be quantified. Carter Center experts were conservative in accepting only scientific evidence that lent itself to rules of evidence. But the printout also provides general information that should be good for everyone: exercise briskly for 15 to 30 minutes at least three times a week, eat foods low in fat and cholesterol and high in fiber, and learn to recognize and handle stress. A special message warns about how AIDS is spread.

Questionnaires and computer software to run the health risk appraisal are in the public domain and will be made available in early 1988 through a users network of state health departments and universities working with the center. The basic cost of obtaining the program and regular updates is $125 for new providers. The amount later charged to each consumer receiving the health risk appraisal may range from zero to $40, depending on who is offering it.

©1987 Cristine Russell

Cristine Russell, on leave from the Washington Post, is reporting on the risks of everyday life.